Part 1: Introduction, historical background and Edinburgh connections

Is there any ophthalmologist who has not missed a pituitary tumour? Hopefully this article will help those currently in practice to avoid such an embarrassment, for unless one keeps in mind that pituitary tumours are common, occur at all ages including children, and can present with minimal symptoms they will be missed. Failure to pick up a pituitary tumour will also be the case unless one accepts that examination of the visual field “should be performed on all patients regardless of their presenting visual symptoms” as emphasised by Walsh and Hoyt [1], who also state that “because it is quick and easy to perform a confrontation visual field should be performed on all patients regardless of their visual complaints” [2].

Harvey Cushing (1869-1939) on the pituitary fossa:

“Here in this well concealed spot, almost to be covered by a thumb-nail, lies

the very mainspring of primitive existence.”

The incidence of pituitary tumours is 1.87 cases per 100,000 population and they comprise 10-15 % of all intracranial tumours and are the commonest cause of a compressive optic neuropathy. Today many such tumours are discovered incidentally following brain neuro-imaging performed for other reasons, and are often found at routine post mortem examination.

Figure 1: Professor Harvey Cushing and quotation (opposite). © Wellcome Images,

a website operated by Wellcome Trust, a global charitable foundation based in the United Kingdom.

In Edinburgh there has been a long-standing interest in pituitary tumours and their management, along with a close collaboration between our ophthalmologists and neurosurgeons. Our first neurosurgeon was the famous south Edinburgh born Norman Dott (1897-1973) who went to Boston in 1923 on a Rockefeller Fellowship and spent a year with Professor Harvey Cushing (1869-1939), the famous pioneer American neurosurgeon (Figure 1), learning among other things the technique of trans-sphenoidal hypopysectomy, which he put into practice on his return to Edinburgh.

The then Dr Dott set up our first neurosurgical department in Ward 20 of the old Royal Infirmary and also operated in a private nursing home at 19 Great King Street, a converted Georgian terrace house. In 1947 he was appointed to the first Forbes Chair of Surgical Neurology in University of Edinburgh and over time gained recognition as one of the world’s leading neurosurgeons.

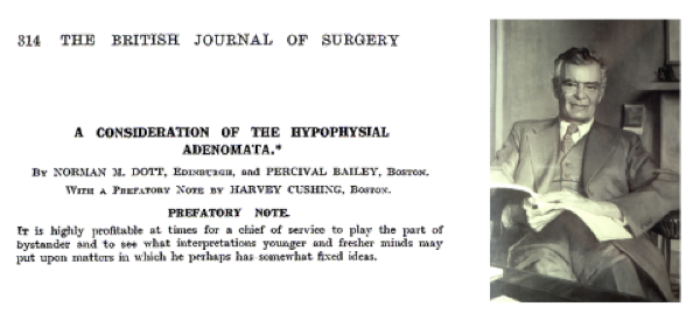

Figure 2: Professor Norman Dott with title and prefatory note by Harvey Cushing of his 1925 paper from the British Journal of Surgery. It reads “It is highly profitable at times for a chief of service to play the part of bystander and to see what interpretations younger and fresher minds may put upon matters in which he perhaps has somewhat fixed ideas.” Photo courtesy of The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh.

In 1925 Dott and Percival Bailey, a pathologist, published [3] a review running to 52 pages (Figure 2) of 162 cases of pituitary adenomas treated by Dr Cushing, whose prefatory remarks to the paper should be noted by all senior consultants and supervisors.

This paper was the first review of Cushing’s cases subsequent to his monograph ‘The Pituitary Body and its Disorders’ published in 1912 [4]. Professor Cushing was conferred with the honorary FRCSEd in 1927 when he came to Edinburgh to attend the Lister centenary celebrations.

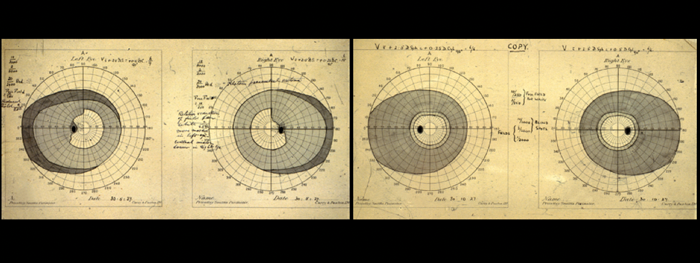

“The patient’s pre and postoperative visual fields from 1927 are shown in Figure 4 and it was from these and a skull x-ray that the diagnosis of a pituitary tumour was made and operation decided upon.”

On his retirement in 1962, Professor Dott was conferred with the freedom of his native city, the silver casket which contained his freedom scroll can be seen in the museum of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (RCSEd) and his biography [5] was published in 1990. He was also a member of the Scottish Ophthalmological Club founded in 1911 and often attended its meetings (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Photograph taken at the 100th meeting of Scottish Ophthalmological Club (SOC) in 1967 on the front steps of the old Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. In the centre of the front row are Professor George Scott (President SOC) flanked by Sir Stewart Duke-Elder on his right and Professor Dott on his left. The author is in the second row fifth from right behind Professor Wallace Foulds.

In 1988, I was referred a former patient of Professor Dott, who had been operated on at Great King Street in 1927 at 10 years of age for a pituitary tumour. Her case notes were retrieved from the Royal Infirmary archives where Dott’s early records had been preserved; from these it was found that the girl had a trans-sphenoidal hypopysectomy under open ether anaesthesia; her case history was later reported in the Scottish Medical Journal [6]. The patient became a professional photographer, whose photographs of Dott are in his biography [5] and she died aged 84 of natural causes. The patient’s pre and postoperative visual fields from 1927 are shown in Figure 4 and it was from these and a skull x-ray that the diagnosis of a pituitary tumour was made and operation decided upon.

Figure 4: Pre (left) and postoperative (right) visual fields charted by Dr Sinclair in 1927 in the

10-year-old patient with a pituitary tumour. Note the upper temporal defects respect the mid line.

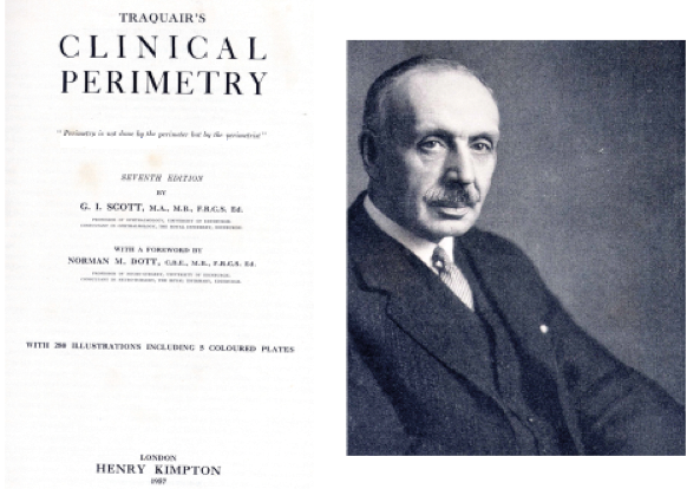

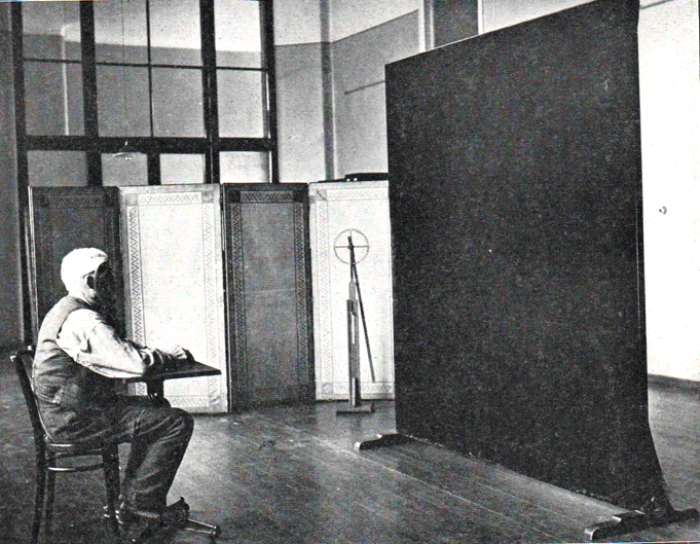

The patient’s visual fields were performed and charted by Dr Arthur Sinclair (1868-1962), who introduced clinical perimetry into the UK following his return from Denmark in 1925, having observed in the clinics of H Ronne and JP Bjerrum. His work was extended and elaborated by his junior colleague in the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary Eye Department Dr HM Traquair (1875-1954), who in 1927 published the first UK book on clinical perimetry entitled An Introduction to Clinical Perimetry which became a world classic [7]. The 1957 seventh edition was renamed Traquair’s Clinical Perimetry (Figure 5), authored by the first Forbes Professor of Ophthalmology in Edinburgh University, Professor George I Scott, and its introduction was written by Professor Dott. From the mid 1920s Bjerrum screen perimetry (Figure 6) became the standard method of perimetry in Edinburgh, which then spread throughout the UK and worldwide [7].

Figure 5: Dr HM Traquair and title page of Traquair’s Clinical Perimetry 1957. The sub-heading reads: “Perimetry is not done by the perimeter but by the perimetrist.” Photo courtesy of The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh.

Figure 6: Photograph taken in the perimetry room of the old Eye (Moray) Pavilion of Edinburgh Royal Infirmary showing 2 metre Bjerrum screen, and on its left side Sinclair’s rule used for charting from the unmarked screen. From Traquair’s Clinical Perimetry. London: H Kimpton; 1957.

“Because it is quick and easy to perform a confrontation visual field should be performed on all patients regardless of their visual complaints.” Walsh and Hoyt [2]

Dr Sinclair (1933-5), Dr Traquair (1939-41) and Professor Scott (1964-6) (Figure 7) were all Presidents of The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, bringing the total of local ophthalmologists who held this office to six, the others being William Wallace in 1871-3, Douglas Argyll Robertson in 1875-7 (Figure 7) and Sir George Berry in 1910-12. Argyll Robertson (1837-1909) of pupillary fame [8] (Figure 8) was appointed the first lecturer in diseases of the eye at Edinburgh University in 1883, he was also a renowned golfer, member of Muirfield GC and won the Gold Medal of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews on four occasions [9].

Figure 7: Photograph of Professor George Scott, President RCSEd at a diploma conferring ceremony. Taken from Figure 24 in A Fortunate Apprentice by John F Shaw. The Memoir Club; 2010.

Figure 8: Portrait of Douglas Moray Cooper Lamb Argyll Robertson in court dress which hangs in the main corridor of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh.

References

1. Miller NR, Subramanian PS, Patel VR. In Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology: The Essentials. 3rd edition, Philadelphia; Wolters Kluger: 2016; Section 1, Chapter 1:7.

2. Miller NR, Newman NJ. In Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology: The Essentials. Philadelphia; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 1999; Section 1 Chapter 1:26.

3. Dott NM, Bailey P. A Consideration of the Hypopyseal Adenomata. Brit J Surgery 1925;13:314-66.

4. Cushing H. The Pituitary Body and its Disorders. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1912.

5. Rush C, Shaw JF. With sharp compassion – Norman Dott Freeman Surgeon of Edinburgh. Aberdeen University Press; 1990.

6. Cullen JF. Mutlukan E. Remembrances of things past: A case from 1927. Scot Med J 1992;37:27-8.

7. Duke Elder S, Scott GI. System of Ophthalmology Volume 12: Neuro-Ophthalmology. London; Kimpton: 1971;2:11.

8. Argyll Robertson D. On an interesting series of eye-symptoms in a case of spinal disease, with remarks of the action of belladonna on the iris etc. Edinburgh Medical Journal 1869;14:696-708.

9. Almond R. The Barbers and the Leeches. Surgeons News 2016;15:64.

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME