Part 3: Clinical features, assessment and management

As previously mentioned in this treatise [1] pituitary tumours are common, occur in all age groups and can present with anything from minimal visual symptoms to complete blindness in one or even both eyes. In a recent report from one neuro-ophthalmology clinic in Singapore 90 cases were seen over a period of nine months [2]. The relevant clinical features and investigation will now be discussed:

- Basic examination of visual acuity and colour vision may be normal but on the Snellen chart the letters corresponding to those in the patient’s temporal fields may be missed, and on the Ishihara plate one of the figures of the double digits again may be difficult to decipher. Pupil reactions may be normal or impaired depending on the severity of the visual loss.

- Optic nerve appearance can be normal even in the presence of a substantial tumour but with advanced compression of the visual pathway the disc will present a chalky white pallor all over. In the presence of a bitemporal hemianopia the disc will have so called ‘bow tie’ pallor. This is explained as follows: the crossing axons from the nasal retina enters the nasal part of the disc, but as the retina is bisected at the macula, not at the disc, half the macular axons are also nasal to centre and these crossing axons enter the temporal part of the disc, thus giving rise to temporal pallor and along with the nasal pallor ‘bow tie’ pallor is apparent. The upper and lower parts of the disc are occupied by arcuate axons curving above and below the papillo-macular bundle from the more peripheral temporal retina and, of course, these axons do not cross in the chiasma so that the upper and lower parts of the disc can be normal. Optic disc swelling / papilloedema does not occur unless in rare cases where a very large tumour has invaded the third ventricle, blocked the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) produced hydrocephalus and increased intracranial pressure (Figure 1).

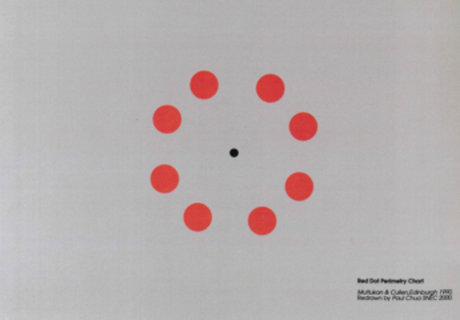

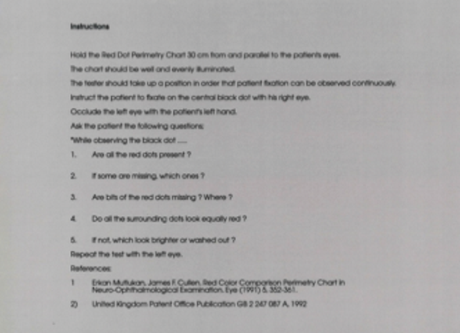

- Visual fields (VF): The classical field defect of chiasmal compression from a pituitary tumour is bitemporal starting in the upper temporal area and progressing clockwise in the right eye and anticlockwise in the left, so that a patient may eventually be left with only residual vision in his / her upper nasal fields. As already mentioned [3] in the presence of a pre or post fixed chiasma such classical field defects may not be encountered. Assessment of VF is now usually performed by Humphrey field analysis which was designed for glaucoma investigation and can only test up to 30 degrees of the field, so that a full field examination with the Goldmann or similar perimeter is also required. Another useful test, especially for early chiasmal compression is with the red dot perimetry chart described elsewhere [4,5] (Figure 2) and which can even be performed by the patient him / herself as the instructions are on the reverse. This test can also be used in the ward setting for bed bound and for wheelchair patients.

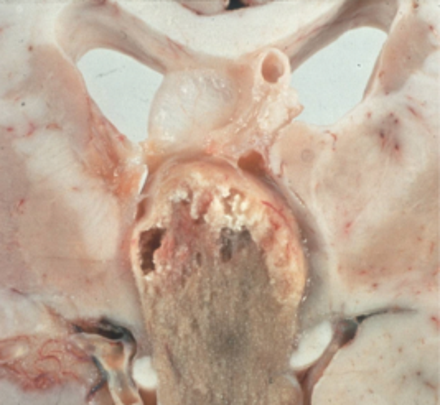

Figure 1: Pathological specimen of a large pituitary tumour invading the third ventricle.

Figure 2: Red dot perimetry chart (top) with instructions for use on reverse (bottom).

Investigation

In the eye clinic where non-secreting tumours are most likely to be seen the vital hormonal evaluation is the prolactin level and if this is normal the ophthalmologist has to make a decision on neuroimaging. A CT or MRI scan of the brain with contrast will reveal the presence of a pituitary tumour but is in essence only a diagnostic / screening investigation. A MRI of the pituitary area (not of the brain) with contrast is required by the neurosurgeon if surgery is being considered, and this investigation is best left to him / her along with arrangements for full pre-operation endocrine evaluation.

“If untreated a pituitary tumour will continue to expand slowly over months or years, most commonly upwards causing further compression of the visual pathway and eventually blindness.”

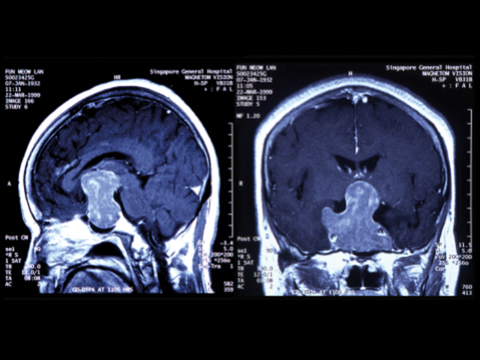

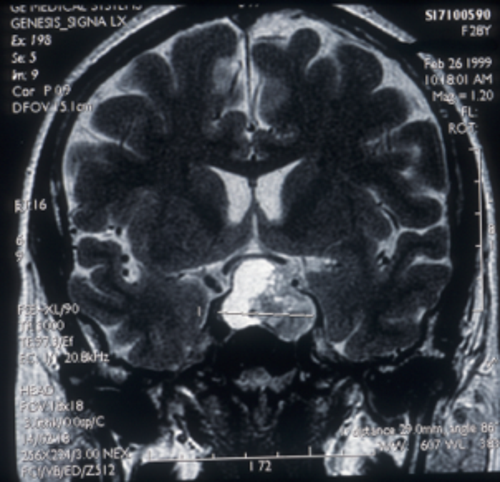

Figure 3: MRI scans showing a large pituitary tumour with (left) saggital image

showing upward extension and (right) coronal image, showing invasion of both cavernous sinuses.

Tumour progression

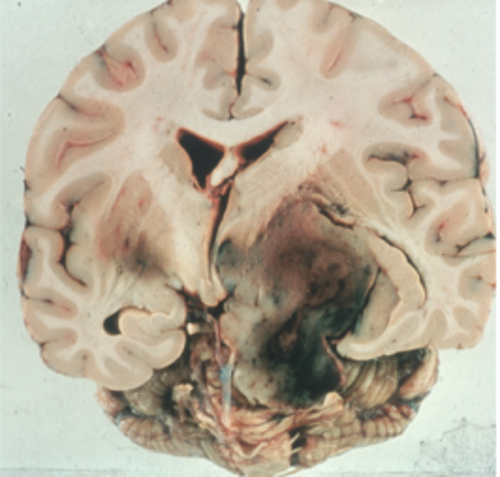

If untreated a pituitary tumour will continue to expand slowly over months or years, most commonly upwards (Figure 3, left) causing further compression of the visual pathway and eventually blindness. Lateral spread is into the cavernous sinus (Figure 3, right) when an ocularmotor palsy, usually the sixth, will develop. Once the cavernous sinus is invaded, a tumour in this area cannot be safely removed. Rarely a tumour can extend even further into the temporal or parietal lobe of the brain (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Pathological specimen of a large pituitary tumour extending laterally into

the temporal and parietal lobes of the brain with intra tumour haemorrhage.

Pituitary apoplexy

Pituitary apoplexy is correctly defined as acute haemorrhagic necrosis of a pituitary adenoma leading to rapid tumour expansion accompanied by headache, lethargy, coma and increased intracranial pressure (Figure 5). Development of a cranial nerve palsy associated with tumour expansion is not apoplexy nor is a localised haemorrhage into a tumour (Figure 6) although these may result in an acute exacerbation of symptoms.

Figure 5: Post mortem specimen of pituitary apoplexy showing a haemorrhagic

pituitary tumour with blood in the surrounding CSF spaces.

Figure 6: MRI scan coronal image showing haemorrhage into a pituitary tumour.

Surgical treatment

Trans-sphenoidal surgery is now the standard operation for pituitary tumours although some large tumours may require a transcranial approach. In many cases, improvement of visual function can occur within 24 hours of surgery. Overall 75-95% of patients improve in respect of visual acuity and or visual fields. Sometimes with longstanding tumours visual fields may improve after months or rarely after years.

In some centres routine postoperative radiotherapy is advised but this will result in severe hypopituitarism requiring long-term and expensive hormone replacement treatment.

The optic disc will always become pale after operation even if not so beforehand.

Recurrence

Pituitary tumours have a significant recurrence tendency following treatment, either medical or surgical, so patients require lifelong follow-up. Reported recurrence after five years following surgery alone is 7-35% but with additional radiotherapy the recurrence rate is reduced to 7-13% over five years [6].

References

1. Cullen JF. Pituitary tumours: why are they so often missed? Part 1: Introduction, historical background and Edinburgh connections. Eye News 2017;23(6):20-4.

2. Cullen JF, Thavaratnam LK. Neuro-ophthalmic disease patterns in Southeast Asia with particular reference to giant cell arteritis. Eye News 2016;22(6):26-9.

3. Cullen. JF. Pituitary tumours: why are they so often missed? Part 2: Clinical varieties, anatomical considerations and case report. Eye News 2017;24(1):18-20.

4. Mutlukan E, Cullen JF. Red colour comparison perimetry chart in neuro-ophthalmological examination. Eye 1991;5:352-61.

5. Cheng JF, Cullen JF. Red colour comparison perimetry chart and Humphrey visual fields in patients with pituitary tumours. Asian J Ophthalmol 2008;10:16-8.

6. Miller NR. In Walsh & Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology 4th Edition. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins;1988:1466-7.

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME