The VISION 2020 LINKS Programme is part of the ‘VISION 2020: The Right to Sight’ global initiative to eliminate avoidable blindness [1]. The LINKS Programme works with overseas eye departments to help identify priorities and match their priority needs with suitable UK eye departments. Highlighted as part of the Millennium Development Goals, global health partnerships provide an opportunity to help improve the health sector in developing countries.

At present, 16 of the 28 VISION 2020 LINKS between UK and African hospitals are working towards improved paediatric ophthalmology services. These paediatric LINKS have identified retinoblastoma as a priority eye disease. Ophthalmologists in Africa often receive these patients at a late stage, referring them on to oncologists. Usually the only possible treatment is palliative.

In this article we present the findings of a situation analysis of retinoblastoma in 10 of the 16 paediatric VISION 2020 LINKS. This includes analysis of the barriers children and their families encounter and some suggestions for the way forward. This work was carried out by Lindsay Hampejsková as part of her MSc in Public Health for Eye Care at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. She has developed a Resource Estimation Tool to measure the incidence of retinoblastoma and the workload it would create for ophthalmologists and other healthcare workers if it was to be treated successfully. This work will be published separately. The article also includes case studies from two of the paediatric VISION 2020 LINKS, which illustrate the issues faced by clinicians treating children with retinoblastoma in Africa.

VISION 2020 Paediatric LINKS: countries shown in blue have LINK partnerships

working on paediatric ophthalmology – 16 LINKS in 13 countries.

Retinoblastoma in sub-Saharan Africa

Globally, retinoblastoma affects approximately 8,000 children per year and accounts for roughly 5% of all childhood cancers [2]. In Africa, retinoblastoma is common in children’s cancer wards and eye departments. The number of cases in Africa is estimated to be over 1950 per year, whereas England has between 50 and 60. There is no known primary prevention for retinoblastoma, as the tumour forms following a genetic mutation in a progenitor retinal cell, affecting one or both eyes. It can be genetic (germline) or sporadic [3]. A child affected by retinoblastoma may begin to develop tumours in utero up until approximately five years of age, although in rare cases adults can be affected.

About 70% of cases are unilateral and could be cured with early detection (detected by leukocoria / white pupil) and enucleation (removal of the affected eye), even in a resource-poor setting [2]. However, most children in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) present with proptosis, orbital swelling or with a large extraocular mass, which are often associated with a poor prognosis [4,5]. The percentage of children who survive retinoblastoma in SSA is very low. From one study in Kenya, survival was calculated to be 26.6% [6]. In the UK, retinoblastoma has consistently had the highest survival of all the childhood cancers over the last four decades; ten-year survival has improved from 87% in 1971-1975 to 99% in 2001-2005 [7]. Surviving children with both eyes affected (bilateral retinoblastoma) face another challenge: blindness, as currently the best form of treatment in SSA is to remove both eyes.

Barriers to eye healthcare for children in SSA

Children in SSA face many barriers to eye healthcare. Major healthcare facilities, and two-thirds of ophthalmologists, are located in the major cities, yet in SSA more than two-thirds of the population live in rural areas. The lack of transport infrastructure and the huge distances involved greatly impact both cost and access to health services. Children with retinoblastoma living in rural areas may be taken to local primary healthcare workers or to traditional healers, but both lack training in detecting abnormalities of the eye and are often disconnected from urban centres where treatment is available [5,8]. In the event that a child does find their way to a healthcare facility, parents often refuse treatment because of the stigma associated with removing an eye, or the family may be unable to afford the cost of treatment, or the child may be given inadequate treatment [2].

Retinoblastoma case study 1

Provided by Dr Sunday Abuh, Paediatric Ophthalmologist, ECWA Eye Hospital, Kano, Nigeria.

Kabiru Idi comes from Wamba village, Akwanga, in Nassarawa State, Nigeria. He was born in July 2012. Kabiru was brought to ECWA Eye Hospital Kano for the first time in August 2014 after several fruitless medical sojourns to different health facilities in Nigeria. According to Kabiru’s mother, they noticed a swelling and tearing on his left eye sometime in October 2013.

She said, when the first signs were noticed, they consulted the local chemist in Wamba where they were given drugs and some eye drops. Two weeks later when it was obvious that there was no improvement, the family was advised by neighbours to seek medical intervention at the National Eye Centre, Kaduna. At the National Eye Centre they were given drugs and eye drops to take home and apply as prescribed.

One month later, a big tumour appeared. Out of confusion, Kabiru’s parents sought advice from many places; eventually they were asked to seek help at Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital, Zaria, Kaduna State. After a series of tests and diagnoses at the hospital, they were told that the eye would be operated on, but the parents had no money for the surgery. In the process of looking for money, a member of the medical staff in the hospital cautioned them that if they allowed surgery on the eye the child would die. He advised them to go to ECWA Eye Hospital, Kano, as that was where he was certain that they would find the solution.

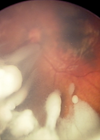

Photos of Kabiru

1. Before treatment.

2. After first course of treatment.

3. Taking his meal after the third course of treatment.

4. In the hospital for his fourth course of treatment.

On 14 August 2014, at ECWA, it was discovered that Kabiru had a case of neglected retinoblastoma already fungating with a huge tumour (see picture above). After thorough examinations and investigations, he was admitted for high dose chemotherapy. Unfortunately, the parents disappeared with the child, only to re-appear three months later. Treatment started with daily dressing and administration of antibiotic drugs, thereafter chemotherapy treatment began as shown below. Normally when the tumour shrinks after chemotherapy we perform an enucleation instead of exenteration. At the time of writing, Kabiru is yet to have an enucleation.

Kabiru and his parents, who suffered stigmatisation from friends and neighbours because of the ugly sight of the tumour, saw the tumour disappear completely after the first course of treatment. Kabiru’s mother, in appreciation to doctors and staff of ECWA Eye Hospital, reported with joy that her baby was now doing excellently. She said he hardly stays at home but is always out playing with friends. He couldn’t eat before and was always crying, but is calm now and eats everything available.

Kabiru continues to thrive for now, but sadly, this will not be sustained beyond the next few months, as the stage of the tumour on presentation means that it will have metastasised and is not curable. At least the availability of chemotherapy has bought some time for the family to enjoy their son.

ECWA Eye Hospital has a long-standing VISION 2020 LINK with the Western Health and Social Care Trust, Altnagelvin Area Hospital, Northern Ireland, led by Paediatric Ophthalmologist Rosie Brennan.

Retinoblastoma case study 2

Provided by Doctors Sharai Shamu and Mayuri Makan, Paediatric Ophthalmologists, Sekuru Kaguvi Eye Unit, Parirenyatwa Group of Hospitals, Harare, Zimbabwe.

In Zimbabwe the outcome for children with retinoblastoma is normally poor, as children present with late stage disease. There are several challenges to be addressed in order for the necessary multidisciplinary treatment to be successful. Besides the need to raise awareness with healthcare providers and in the community, another stumbling block is acceptance by parents. It is a difficult diagnosis for a family to accept when the child is otherwise well. The cosmetic outcome is a challenge and results in parents resisting treatment.

During training visits as part of the VISION 2020 LINK, Ophthalmologists Dr Makan and Dr Shamu learnt about the need for a patient and parent counsellor while breaking bad news. In London, Dr Makan spent a lot of time learning about the support system in place for these patients, which included time with the play specialist and patient support group (Childhood Eye Cancer Trust) at the Retinoblastoma Unit at the Royal London Hospital (Barts Health NHS Trust). Dr Makan witnessed the role of the play specialist in making the patient and parents familiar with the use and care of the artificial eye. Reciprocal visits from Mr Reddy, Lead for Retinoblastoma at Barts, to Harare emphasised the importance of early detection and family acceptance.

A six-month-old boy was referred with a cat’s eye reflex and exotropia and no other symptoms; he was otherwise a bouncing baby. The diagnosis of retinoblastoma was devastating to the new parents. This child was referred by a general practitioner in Harare within a week of an awareness talk given as part of the VISION 2020 LINK visit from our LINK partner, Barts Health in London. This child was referred with intraocular disease by the general practitioner with a high index of suspicion. The approach and counselling was important for the father to accept the treatment offered. The child had an enucleation done and an acrylic implant was placed in the socket via the myoconjunctival technique [9] to improve prosthesis movement following the enucleation. Finally, a prosthesis was placed in the socket to improve cosmesis. To date, he is free from disease.

The retinoblastoma patient following enucleation,

implant and insertion of prosthesis.

We have started to overcome the reluctance of parents for their child to have an eye removed by establishing a support group and encouraging parents to discuss experiences with each other. The nurses in Harare have also become counsellors and co-ordinators.

Lessons learned:

- Initial communication and counselling is critical for acceptance.

- An implant and prosthesis is now offered.

- A nurse with counselling experience was part of the team. She was available for social support without compromising acceptance of treatment.

- She was also the co-ordinator between disciplines so that the child was not lost to follow-up.

Conclusion

A priority in SSA is to work towards earlier detection through education and awareness amongst primary health workers, traditional healers and the wider community in SSA. This will drastically reduce the number of children in SSA who present with advanced, incurable disease and will increase survival rates. Saving children with retinoblastoma requires investment in the healthcare system. There is a need to strengthen primary healthcare, community participation, develop structured referral pathways, create centres of excellence for paediatric ophthalmology and oncology care, establish support groups to enable families to share experience and encourage compliance, and increase the quality and access to pathology services.

The 16 VISION 2020 LINK partnerships that are working together on paediatric ophthalmology are all keen to tackle the problems of treating retinoblastoma in SSA. The LINKS Programme has been seeking funding for this work for several years, but the low incidence of retinoblastoma compared with the other diseases facing children in SSA means that it is not a priority for funders. Readers are asked to consider possible funders that might want to be involved and contact the VISION 2020 LINKS Programme at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

References

1. VISION 2020 LINKS Programme. International Centre for Eye Health.

http://iceh.lshtm.ac.uk/

vision-2020-links-programme/

Last accessed June 2015.

2. Dimaras H, Kimani K, Dimba EA, et al. Retinoblastoma. Lancet 2012;379(9824):1436-46.

3. Retinoblastoma. American Cancer Society.

http://www.cancer.org/cancer/

retinoblastoma/detailedguide/

retinoblastoma-what-is-retinoblastoma

Last accessed June 2015.

4. Nyamori JM, Kimani K, Njuguna MW, Dimaras H. The incidence and distribution of retinoblastoma in Kenya. Br J Ophthalmol 2012;96(1):141-3.

5. Essuman V, Ntim-Amponsah CT, Akafo S, et al. Presentation of retinoblastoma at a paediatric eye clinic in ghana. Ghana Med J 2010;44(1):10-5.

6. Nyawira G, Kahaki K. Survival among retinoblastoma patients at the Kenyatta National Hospital, Kenya. J Ophthalmol East Cent South Africa 2013;August:15-9.

7. Children’s cancers survival statistics. Cancer Research UK

http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/

cancer-info/cancerstats/childhoodcancer/

survival/childhood-cancer-survival-statistics

Last accessed June 2015.

8. Courtright P, Chirambo M, Lewallen S, et al: Collaboration with African Traditional Healers for the Prevention of Blindness. Singapore; World Scientific Publishing Ltd: 2000.

9. Shome D, Honavar SG, Raizada K, et al. Implant and prosthesis movement after enucleation: a randomized controlled trial. Ophthalmology 2010;117(8):1638-44.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME