Poppers retinopathy is a relatively unknown phenomenon which afflicts users of poppers but should be considered as a differential in sudden-onset or sub-acute visual acuity loss – particularly in patients with a history of recreational drug use.

Raising awareness of this condition could help doctors, particularly those working within ophthalmology, general practice or A&E, as there is concern that permanent visual loss can occur in patients who continue to use poppers.

Firstly, ‘poppers’ is the colloquial name for a group of volatile alkyl nitrites, which are inhaled recreationally to provide an immediate and brief sense of euphoria and sexual arousal [1]. They are popular in the men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM) community and are frequently used in ‘chemsex’, due to their mechanism of action, which causes relaxation of the anal sphincter muscles [2]. In 2011, a Stonewall survey measured the UK incidence of recreational popper use in MSM at 31%, compared to 2% of men in general [3]; other national surveys, such as in Canada and the US, measured similar disparities of incidence between MSM and the overall population [4].

The legality of poppers in the UK could be considered as a grey area – the manufacture and sale of alkyl nitrites for human use is illegal, but possession of alkyl nitrites is legal [5,6]. The same government review noted that the overwhelming public perception was that they were legal to sell. This would align with anecdotal evidence regarding the ease of access to poppers, and their ubiquity in sex shops across the UK – sellers bypass laws by marketing poppers as room odourisers, leather cleaners, or imply other alternative uses for these compounds [7]. This is one potential cause for the continuously high incidence in the MSM community.

Poppers, and the dangers associated with their recreational use, have been reviewed twice in the past 15 years by a government review process. While there are other potentially serious sequelae resulting from poppers use, such as methemoglobinemia, the association with retinopathy has not been as well publicised, so it is important to draw attention to this [8].

Firstly, while there is no unified definition of poppers retinopathy, after reviewing the two existing systematic reviews on the subject, it is usually defined by:

- A history of poppers use

- Characteristic evidence of retinal damage

- Characteristic symptoms – namely central visual disruption / distortion and phosphenes.

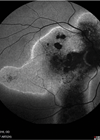

Characteristic evidence of retinal damage is a very broad term – however it has been well described in early papers detailing the phenomenon. Firstly, poppers primarily cause damage at the fovea, with multiple yellow foveal dots often seen on fundus examination [9]. Other fundoscopic changes commonly seen were dome-shaped elevation at the fovea, or less commonly irregularity or hyper-reflectivity at the fovea [10]. Common investigations were spectral domain optical coherence tomography (OCT), OCT-angiography and fluorescein angiography.

Spectral domain OCT findings in poppers retinopathy commonly reveal damage at the junction of the inner and outer segments of the photoreceptor cell layer, known as the ellipsoid zone [7,11,12]. Angiography findings are rarer within the literature, but documented OCT-angiography findings have revealed choriocapillaris alterations; specifically, flow-voids at the choriocapillaris, which are likely related to microvascular compromise [12]. The majority of changes which have been found in poppers retinopathy take place at the macula, and as such many authors refer to the condition as ‘poppers maculopathy’. However, abnormalities beyond the macula have been found using full-field electroretinography [13]. This provides evidence for more diffuse retinal damage, particularly affecting rod photoreceptors. As such, clinicians studying the disease have advocated for the use of ‘poppers retinopathy’ over ‘poppers maculopathy’ as damage can extend beyond the macula [1].

Clinically, poppers retinopathy can be considered to have a heterogenous presentation. Patients can present with unilateral or bilateral involvement (although bilateral is more common), and although the main presenting complaint is generally a reduction in visual acuity, this presents in a variety of different ways [14]. For instance, symptoms can range from visual field defects, most commonly central scotoma, through to glare or blurred vision, metamorphopsia, and finally generalised reduction in visual acuity [14,15].

Generally, central visual field loss or distortion is more common, whereas peripheral field defects and colour vision disturbances are rarer [1]. The range in symptoms is also related to the suspected aetiology. For example, central visual field loss is the most common presenting symptom, which reflects the fact that changes often occur at the fovea. Some users describe having a central ‘bright dot’ in their field of vision, commonly representing a central phosphene [9]. However, there has been documented evidence of retinal changes outside the macula [13], and these may contribute to other symptoms such as peripheral field defects and metamorphopsia.

"It is likely that length and frequency of poppers use drives increased likelihood of developing poppers retinopathy"

In terms of risk factors of developing poppers retinopathy, it is likely that length and frequency of poppers use drives increased likelihood of developing poppers retinopathy. There have been documented cases of patients diagnosed with poppers retinopathy after one isolated use; however, chronic, regular users were generally found to have worse presenting visual acuity, more severe foveal and ellipsoid zone abnormalities, and worse prognoses [14,16,17].

There is currently no established consensus as to the pathogenesis of poppers retinopathy; however, some papers have proposed ideas for how retinal toxicity occurs. Isopropyl nitrite, one of the alkyl nitrites within poppers is a very potent nitric oxide (NO) donor. Current hypotheses pose that sudden changes in ocular perfusion pressure (due to NO’s role as a vasodilator) could precipitate retinal injury [9]. Alternatively, significant NO release could predispose the retina to photic injury through increased photosensitivity [9,18,19].

Interestingly, isobutyl nitrite was previously the most common alkyl nitrite found in poppers; when it was found to be a Class II carcinogen, it was banned from consumer products in 2007 [16]. At this point, it was replaced by isopropyl nitrite, which coincided with the advent of documented poppers retinopathy findings [16]. It is possible that the new compound found in poppers may pose a higher threat to photoreceptor health than the previous isobutyl nitrite, and the banning of a carcinogenic substance may have inadvertently triggered a higher incidence of retinal toxicity and therefore worsened visual morbidity associated with poppers use.

Finally, it is important to discuss any treatment options for poppers retinopathy. As a rare and poorly understood condition, there has not been much evidence for any particular treatment within the literature. The most important (and only evidence-based) treatment is stopping poppers inhalation; encouragingly, many patients recovered completely after prolonged periods of cessation and did not suffer from any permanent visual symptoms [14]. This was unfortunately not the case for all patients, and some did not see measured improvements after poppers cessation [16]. Treatment with oral lutein was associated with good prognostic outcomes in one study, and as such may be considered as a supplementary treatment option in the future [20].

In conclusion, poppers retinopathy is a relatively unknown phenomenon; examination findings are often subtle, even to the experienced ophthalmologist. As such it is important to have a base knowledge of the characteristic presenting symptoms, and investigative findings in order to be aware of it as a differential. Furthermore, it is important to be able to counsel poppers users about this condition, particularly as cessation has been associated with good prognostic outcomes and in many cases, complete restoration of pre-morbid vision.

References

1. Luis J, Virdi M, Nabili S. Poppers retinopathy. BMJ Case Rep 2016:bcr2016214442.

2. Pepper N, Zúñiga ML, Corliss HL. Use of poppers (nitrite inhalants) among young men who have sex with men with HIV: A clinic-based qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2024;24(1):1741.

3. https://www.equality.admin.cam.ac.uk/files/

gay_and_bisexual_men_s_health_survey_2013_.pdf

4. Le A, Yockey A, Palamar JJ. Use of “Poppers” among Adults in the United States, 2015-2017. J Psychoactive Drugs 2020;52(5):433–9.

5. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/

media/66b5e7c40808eaf43b50df8a/

ACMD+report+-+Alkyl+nitrites+-+updated

+harms+assessment+and+consideration

+of+exemption+from+the+PSA+2016.pdf

6. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/

alkyl-nitrites-acmd-exemption-consideration/alkyl

-nitrites-acmd-exemption-consideration-accessible

7. Davies AJ, Kelly SP, Bhatt PR. ‘Poppers maculopathy’--an emerging ophthalmic reaction to recreational substance abuse. Eye (Lond) 2012;26(6):888.

8. Hunter L, Gordge L, Dargan PI, Wood DM. Methaemoglobinaemia associated with the use of cocaine and volatile nitrites as recreational drugs: a review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2011;72(1):18–26.

9. Vignal-Clermont C, Audo I, Sahel JA, Paques M. Poppers-associated retinal toxicity. N Engl J Med 2010;363(16):1583–5.

10. Kanda M, Malik M, Miller M, et al. Poppers maculopathy missed in a patient with cataract highlights the importance of preoperative optical coherence tomography. BMJ Case Rep 2024;17(6):e259477.

11. Audo I, El Sanharawi M, Vignal-Clermont C, et al. Foveal Damage in Habitual Poppers Users. Arch Ophthalmol 2011;129(6):703–8.

12. Romano F, Arrigo A, Sperti A, et al. Multimodal imaging of poppers maculopathy. Euro J Ophthalmol 2019;31(2):NP71–3.

13. Clemens C, Alten F, Loos D, et al. Poppers maculopathy or retinopathy? Eye(Lond) 2015;29(1):148–9.

14. González-Martín-Moro J, Almagro EG, Abreu NV, Serrano FN. Poppers maculopathy: A quantitative review of previous literature. Semin Ophthalmol 2022;37(3):391–8.

15. Davies AJ, Borschmann R, Kelly SP, et al. The prevalence of visual symptoms in poppers users: a global survey. BMJ Open Ophthalmol 2017;1(1):e000015.

16. Davies AJ, Kelly SP, Naylor SG, et al. Adverse ophthalmic reaction in poppers users: case series of ‘poppers maculopathy’. Eye (Lond) 2012;26(11):1479–86.

17. Schulze-Döbold C, Ben Denoun M, Dupas B, et al. Retinal toxicity in users of “poppers”. Ann Intern Med 2012;156(9):670–2.

18. Docherty G, Eslami M, O’Donnell H. “Poppers Maculopathy”: a case report and literature review. Can J Ophthalmol 2018;53(4):e154–6.

19. Fajgenbaum, MAP. Is the mechanism of ‘poppers maculopathy’ photic injury? Eye (Lond) 2013;27(12):1420–1.

20. Pahlitzsch M, Draghici S, Mehrinfar BM. Poppers-Makulopathie (Poppers-associated maculopathy). Klin Monbl Augenheilkd 2013;230(7):727–32.

[All links last accessed April 2025]

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.