Airgun injuries to the eye and orbit can be visually devastating. The pellet need not impact the globe directly to cause visual loss, as the cone shaped orbit may funnel the projectile into the orbital apex and optic nerve. We present two cases of orbital air gun pellet retention.

There are few clear indications for bullet or pellet removal, which include bullets found in joints, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or the globe of the eye [1]. In cases with mechanical restriction but good visual prognosis, it has been recommended to remove pellets [2]. Moreover, fragments causing nerve impingement or lodged in vessel lumens should be removed. In rare instances, foreign body removal may be undertaken where a bullet or pellet is required for medico-legal evidence [1]. In cases of suspected occult globe ruptures, enucleation may be prudent to avoid the risk of delayed sympathetic ophthalmia [3]. In addition to the physical effects of a retained bullet or pellet there are psychological harms, which can be overcome by removal of orbital foreign bodies even in cases with poor visual prognosis [4].

Lead intoxication can be particularly harmful in children where it can have significant impact on neurological development, on occasion even when lead levels are below the recommended treatment threshold [5]. Symptoms of lead intoxication include colicky abdominal pains, stomatitis, polyneuritis with wrist drop, and encephalopathy. Local toxicity with orbital foreign bodies could include cranial nerve palsies and optic neuropathy [2]. However, serum lead levels have repeatedly been found to be normal with retained intra-orbital foreign bodies. With current airgun pellet specifications, intoxication is not expected from intra-orbital airgun pellets, and no late complications found [2,3,6]. Greater risk of absorption is found in joints and synovial fluid as compared to soft tissue [7].

Case one

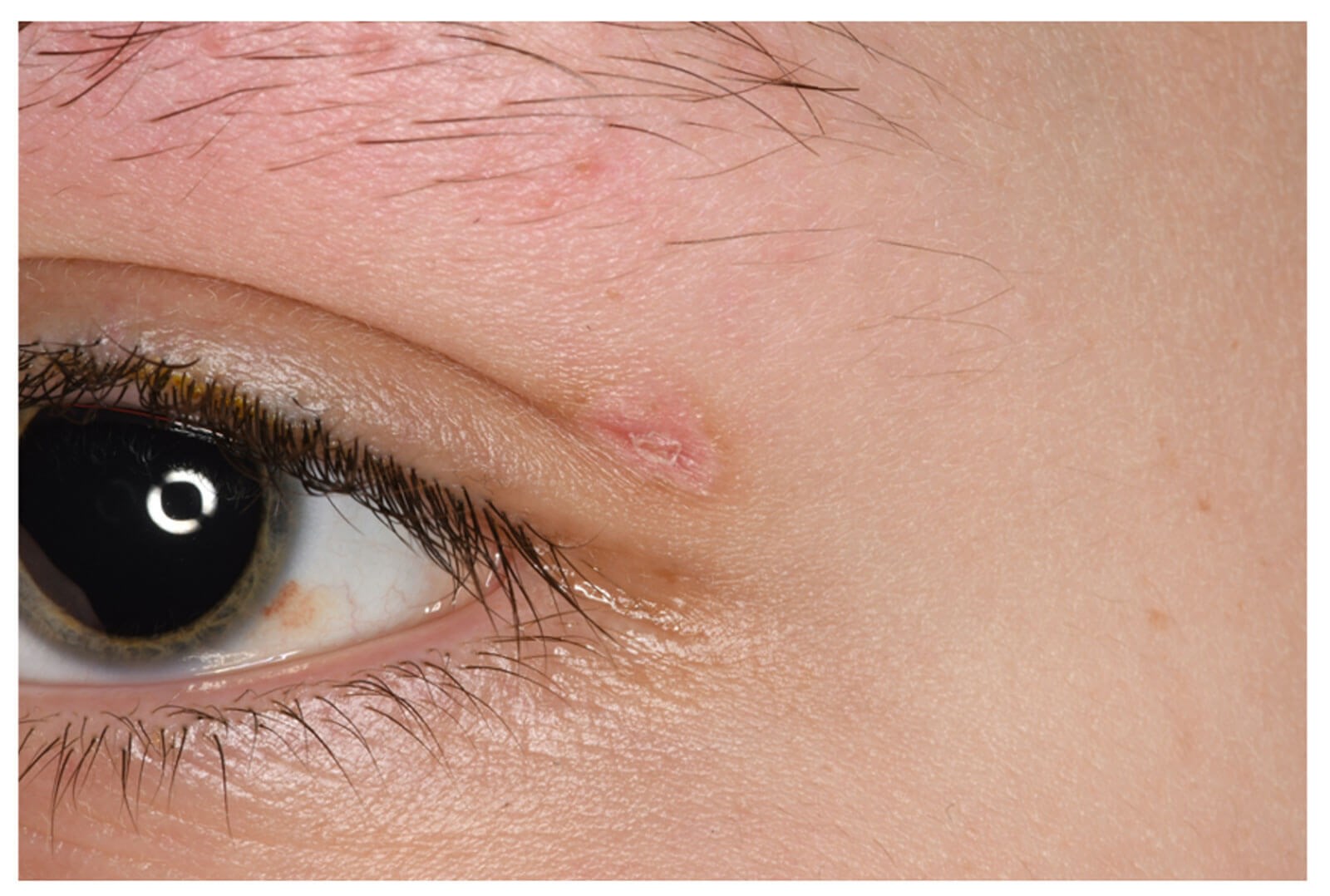

A 14-year-old Caucasian male presented two days after claimed blunt injury to the left eye. Presenting visual acuities were 6/4 in the right eye and hand movements nasally, at 0.1m, in the left. Right eye examination was unremarkable. There were minimal external signs of injury to the left; only a small subconjunctival haemorrhage and sub-brow laceration, which had started to heal by presentation (Figure 1).

Figure 1: External eye image of the left eye with small subconjunctival haemorrhage at 4 o’clock and a healing sub-brow laceration.

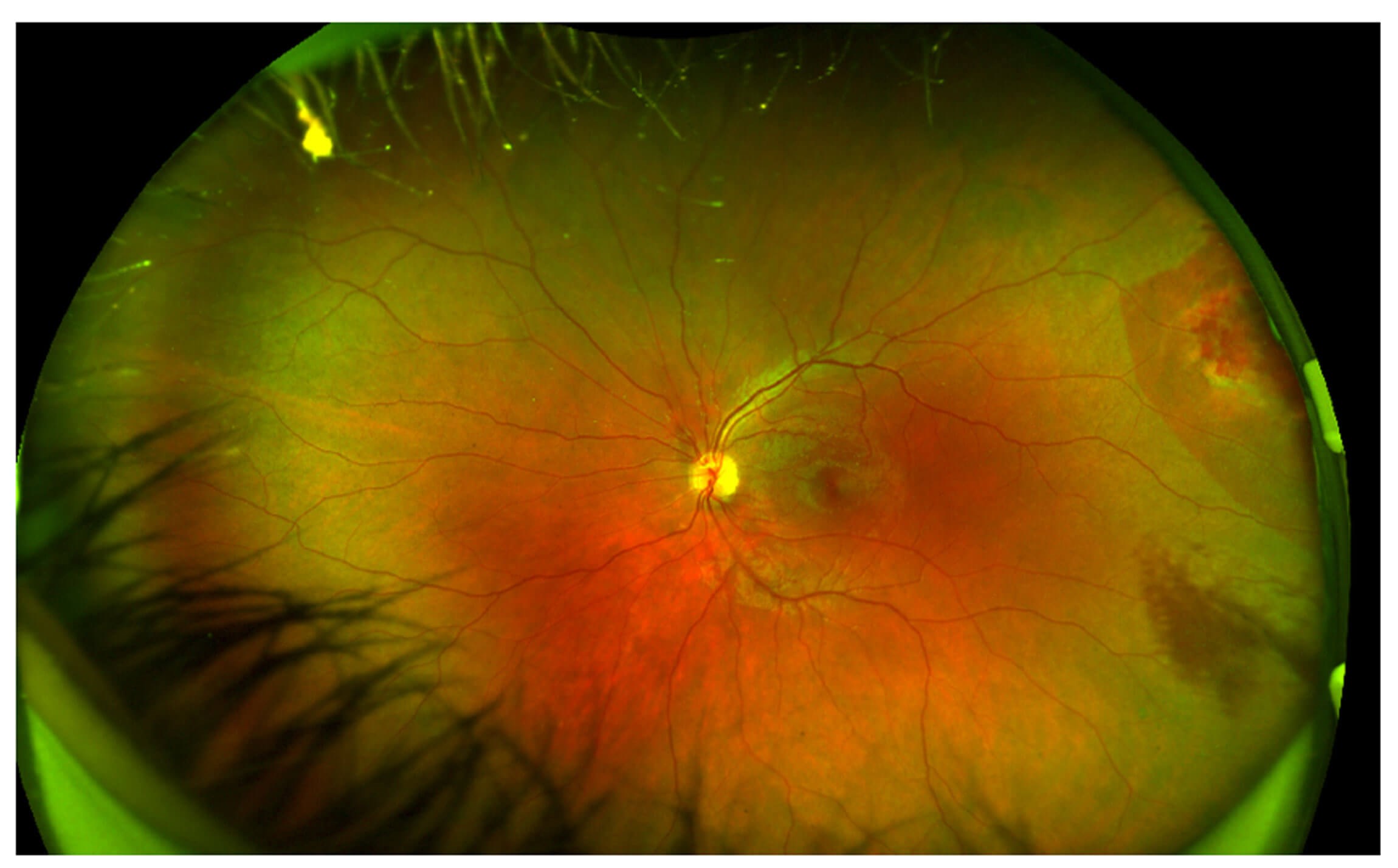

Left relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) was noted and posterior segment examination revealed vitreous haemorrhage, mild optic disc swelling and temporal choroidal rupture in the left eye (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Wide field imaging of retina of the left eye showing mild optic disc swelling nasally and temporal choroidal rupture in the left eye.

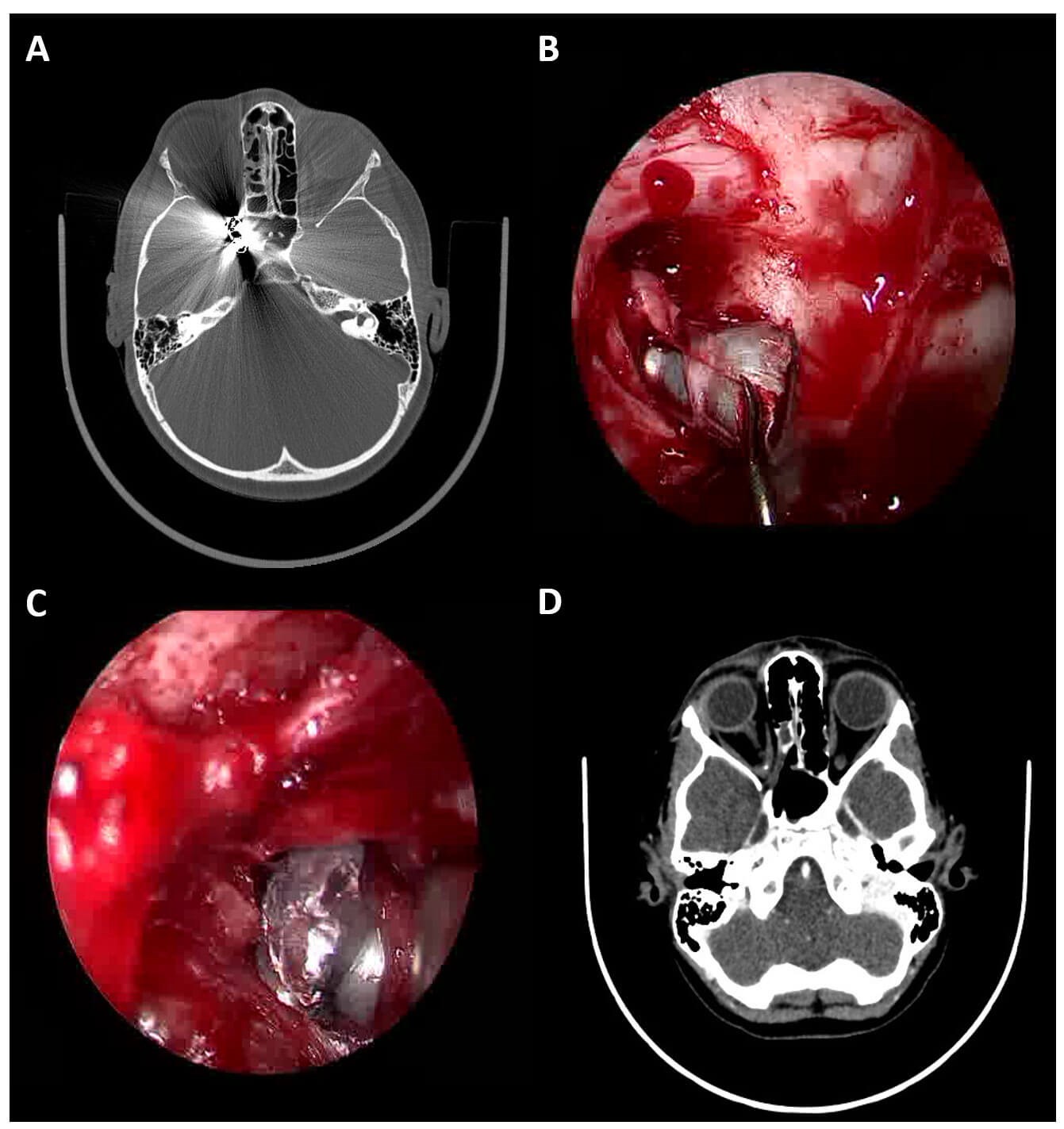

Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the orbits was requested due to complete loss of abduction of the left eye on ocular motility testing. This revealed an air rifle pellet lodged in the left lateral rectus muscle, near the orbital apex, adjacent to the optic nerve (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Axial CT images showing metallic foreign body (pellet) lodged in the left lateral rectus muscle, near the orbital apex, adjacent to the optic nerve.

Management initiated included intravenous (IV) cefotaxime and metronidazole and three days of pulsed IV methylprednisolone followed by a tapering dose of oral prednisolone. Onward referral to our tertiary unit was made and safeguarding instigated. On review, ganglion cell layer cells had already been noted to be reduced in the left eye compared with the right on OCT. Despite the poor visual prognosis, the patient and guardian opted for surgical exploration, which was performed via a transconjunctival approach. Though the pellet was located, attempted removal was unsuccessful and postoperative CT showed the gun pellet lodged at the orbital apex adjacent to the inferior orbital fissure and a second fragment in the left lateral rectus. An additional tiny intraconal foreign body material was noted adjacent to the optic nerve (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Axial CT images showing bone window (left) and soft tissue window (right), revealing the gun pellet lodged at the orbital apex adjacent to the inferior orbital fissure and a second fragment in the left lateral rectus.

It was decided that the case should not be for further surgical input, but he is being monitored and has had no side effects of lead intoxication over one year follow-up.

Case two

A seven-year-old Caucasian male was accidentally shot with an air rifle. He presented to the emergency department of our unit where he was noted to have two small entry wounds in the skin of the medial canthus of the right eye. Vision was recorded as hand movements on the right, intraocular pressure was 27mmHg in the right eye. He had a right complete ptosis and total ophthalmoplegia, including of torsion. There was no proptosis and the globe retropulsed easily. The globe was intact, subconjunctival haemorrhage was noted nasally. The right pupil was fixed and dilated; there was a right RAPD by reverse RAPD check. Dilated fundal examination of the right eye was normal. Examination of the left eye and periocular area was normal.

Figure 5: (a) axial plain CT head (bone window) showing two metallic foreign bodies at the orbital apex and within the optic canal; (b) endoscope image of pellet being extracted from the orbital apex via a trans-nasal route; (c) endoscope image of a second pellet being extracted from the orbital apex via a superior skin crease approach; (d) follow up axial CT head (brain window) showing retained small metallic fragments following removal of the two large pellets.

Initial investigation involved plain CT head (Figure 5a) which showed two pellets located at the orbital apex in the path of the optic nerve. There were comminuted fractures of the lamina papyracea and radiopaque fragments were seen in the medial orbit. Intracranially there was evidence of subarachnoid haemorrhage. Oral co-amoxiclav and metronidazole were started along with oral prednisolone (doses adjusted for weight). The patient was admitted for observation and over the coming days the vision became no perception of light (NPL). The complete ophthalmoplegia persisted. These findings are consistent with severe damage to the optic nerve and cranial verves III, IV and VI at the orbital apex.

The decision was taken to attempt surgical removal of the pellets despite the poor visual prognosis in order to provide pellets for evidence to the police and because the constituents of the pellets were unknown. Given the young age of the patient, it was felt that the possibility of lifelong lead exposure made surgical removal the optimal management plan. Due to the previous failed pellet extraction using a transconjunctival approach, a combined trans-skin crease and trans-nasal approach was taken as a combined case involving ophthalmology and otorhinolaryngology. Two pellets were recovered (Figures 5b, c). Follow up CT head and orbits revealed persistent small metallic fragments within the right orbit (Figure 5d). MRI will therefore be contra-indicated lifelong as these multiple tiny fragments will not be retrievable.

The postoperative course was complicated by right corneal epithelial breakdown secondary to loss of corneal sensation. He also suffered from periocular pain and intense pruritis which was likely secondary to damage to the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve as it exits the superior orbital fissure at the orbital apex. Pregabalin therapy was initiated to control the pain and pruritis. At six months post injury the right eye vision remains NPL, the two air rifle pellets have been removed, but small metallic fragments remain. Abducens nerve function has returned on the right but he continues to have right oculomotor and trochlear nerve palsies.

Discussion

Intra-orbital metallic foreign bodies are uncommon occurrences, causing significant ocular morbidity. The extent of the damage to the eye and orbit is dependent on the ballistic property of the missile (velocity) and many eyes are perforated at the time of trauma or significant optic nerve damage occurs. Visual prognosis is often poor, and many eyes will be enucleated [6]. Modern airsoft guns (also known as pellet or ball-bearing (BB) guns) fire round metallic, ceramic or plastic pellets at a high velocity. There is much literature about the eye and life-threatening injuries resulting from these devices. With current airgun pellet specifications, lead intoxication is not expected from intra-orbital airgun pellets, and no late complications have so far been described [2,3,6].

Retained intra-orbital metallic foreign bodies can cause a variety of signs and symptoms, depending on their location within the orbit, size and the composite material. Surgical removal remains controversial, many authors advocating they should be left in situ unless patients report pain, inflammation or increasing disability [6]. The risks of extraction must be balanced with the risk of leaving the foreign body in situ. Most metals are inert, causing no ocular disturbances and can be retained without problems. However, there are three types of metals which can lead to a marked inflammatory response: iron, copper and lead.

Systemic lead toxicity was frequent in the 1800s and early 1900s, but recent reports are less common due to developments in ammunition manufacturing and encapsulation. There is greater risk of absorption in joints and synovial fluid as compared to soft tissue, muscle or bone [7]. Lead intoxication can be particularly harmful in children where it can have significant impact on neurological development, on occasion even when lead levels are below the recommended treatment threshold [5]. Symptoms of lead intoxication include colicky abdominal pains, stomatitis, polyneuritis with wrist drop, and encephalopathy. A microcytic anaemia is often found, and ocular complications arise in 1–2% of cases with systemic toxicity. Papilloedema, retinal haemorrhages, cranial nerve palsies and optic neuropathy have also been described [2].

Local toxicity with orbital foreign bodies can result in siderosis bulbi; deposition of metal within surrounding tissues can occur with iron, copper and lead. The final location of the retained metal can affect the chance of toxicity. If within soft tissue, it can become encapsulated in dense fibrosis and is unlikely to cause poisoning. Animal studies have determined ocular penetration of iron when placed directly next to the sclera and can result in focal retinal and choroidal atrophy near the sites of extra bulbar iron placement [8]. The degree of iron absorption and risk of damage correlates with the amount of iron present and how much is in contact with the sclera [8]. Iron accumulation occurs faster in the vitreous and aqueous humour; as opposed to lens or cornea, and can result in glaucoma, cataract, iris changes, mydriasis or optic atrophy. Symptoms may develop within days or years.

There are many reports of retained metallic intra-orbital foreign bodies being well tolerated for several decades. Ho, et al. describe a series of 38 patients with retained metallic foreign bodies, 95% of whom had no late secondary complications [6]. Even in cases where significant ocular damage has occurred, metallic remnants are well tolerated by surrounding tissues and no adverse sequelae were noted. They report one patient developing a sterile inflammatory orbital cyst (presenting like orbital cellulitis) 25 years after their initial injury, requiring surgical drainage and surgical removal of shotgun pellet. Another patient developed diplopia due to mechanical restriction of the medial rectus due to bullet fragments, requiring a medial orbitotomy. Diagnostic serum lead levels were performed for 12 patients and reported as normal. Sharif, et al. describe five cases within their series of 41 who had retained pellets, none of whom had lead poisoning signs or symptoms, which they hypothesised was due to the small mass of a single pellet, and modern pellets comprising of insoluble lead amalgams [9]. In the absence of clinical indications, estimations of serum lead levels were not advocated.

There is some evidence for potential delayed lead poisoning. Bhoi, et al. report a patient who presented with recurrent episodes of abdominal pain, constipation, and progressive weakness over several years, between which he was asymptomatic [10]. He was experiencing hallucinations, dysphagia and VII, IX and X cranial nerve palsies and other neurological symptoms. He gave a history of gunshot injury 30 years previously, and radiography showed two pellets in his posterior orbital fossa. Blood-lead levels were ten times higher than normal. Once treated with antibiotics and nutritional supplements, sequential blood lead levels normalised, and his systemic symptoms resolved. Magnetic resonance angiography revealed a cerebral aneurysm which may be incidental or vasculopathy but required no intervention. Other literature has described cerebral aneurysm with chronic lead poisoning.

Other indications for pellet removal are the development of unrelated medical conditions which required serial MRI imaging (which is contraindicated in the presence of metallic remnants). Cole, et al. describes a rare case where a BB gun pellet caused systemic allergic response in a child with a known allergy to nickel. The systemic allergic symptoms resolved following magnet-assisted removal of the pellet [11]. It is widely accepted that pellets located in joints, CSF or the globe should be removed [6]. Additionally, psychological harm from the knowledge of a retained projectile must be considered and can be alleviated by pellet removal [7].

Conclusion

This case pair raises some key learning points, primarily that there is conflicting evidence within the literature regarding the management of intra-orbital firearm projectiles. There is some evidence that systemic or local toxicity from the metals in projectiles is rare. However, there is very little information in the literature regarding the risk from systemic toxicity for paediatric patients. Given that the pellets in the cases reported here would be in situ for many decades if an average life expectancy is assumed, it was felt that attempts at removal were prudent. The possible effects of systemic metal toxicity on development in young people were also a factor, as was the importance of the pellets for evidence in the second case. There are also learning points regarding surgical technique. In the first case, a transconjunctival approach was not successful, as it provided insufficient access. This understanding was carried forward to the second case, where a combined approach with ENT colleagues, and a simultaneous trans-skin crease and trans-nasal approach permitted retrieval of the projectiles.

References

1. Dienstknecht T, Horst K, Sellei RM, et al. Indications for bullet removal: overview of the literature, and clinical practice guidelines for European trauma surgeons. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2012;38(2):89–93.

2. Jacobs NA, Morgan LH. On the management of retained airgun pellets: a survey of 11 orbital cases. Br J Ophthalmol 1988;72(2):97–100.

3. Bowen DI, Magauran DM. Ocular injuries caused by airgun pellets: an analysis of 105 cases. Br Med J 1973;1(5849):333–7.

4. Tian Y, Wang J, Yang S, et al. [Clinical observation on removal of small foreign bodies touching the optic nerve in the deep orbital region]. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi 2014;50(5):360–3.

5. Naranjo VI, Hendricks M, Jones KS. Lead Toxicity in Children: An Unremitting Public Health Problem. Pediatr Neurol 2020;113:51–5.

6. Ho VH, Wilson MW, Fleming JC, Haik BG. Retained intraorbital metallic foreign bodies. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2004;20(3):232–6.

7. Moazeni M, Mohammad Alibeigi F, Sayadi M, et al. The Serum Lead level in Patients With Retained Lead Pellets. Arch Trauma Res 2014;3(2):e18950.

8. Gerkowicz K, Prost M, Wawryzniak M. Experimental ocular siderosis after extra bulbar administration of iron. Br J Ophthalmol 1985;69(2):149–53.

9. Sharif K, McGhee C, Tomlinson RC. Ocular trauma caused by airgun pellets: a ten-year survey. Eye 1990;4(Pt6):855–60.

10. Bhoi SK, Naik S, Kalita J, Misra. Pellets in the eye: cerebral aneurysm and encephalomyeloneuropathy as presenting syndromes. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2018;27(12):3670–2.

11. Cole S, Eftekhari K, Anderson R, Oberg T. Systemic allergic response in the setting of a metallic intraorbital foreign body with intraoperative magnet-assisted retrieval. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2017;33(4):e102–4.

Acknowledgements: Literature searches, duplicates screening and article summaries provided by Derick Yates, Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Trust Library and Knowledge service.

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.