Injuries to the eye have been widely reported in medical literature due to a variety of mechanisms causing significant morbidity and occasional unexpected mortality for the patient [1]. It is often wrongly assumed that air gun pellets lack this potential.

A limited number of large case series have been reported [2,3]. The ballistic properties are responsible for the immediate damage and smaller foreign bodies (FB) often, but not always, lack the kinetic energy to penetrate deeper structures. Many suffer permanent visual impairment or complete blindness.

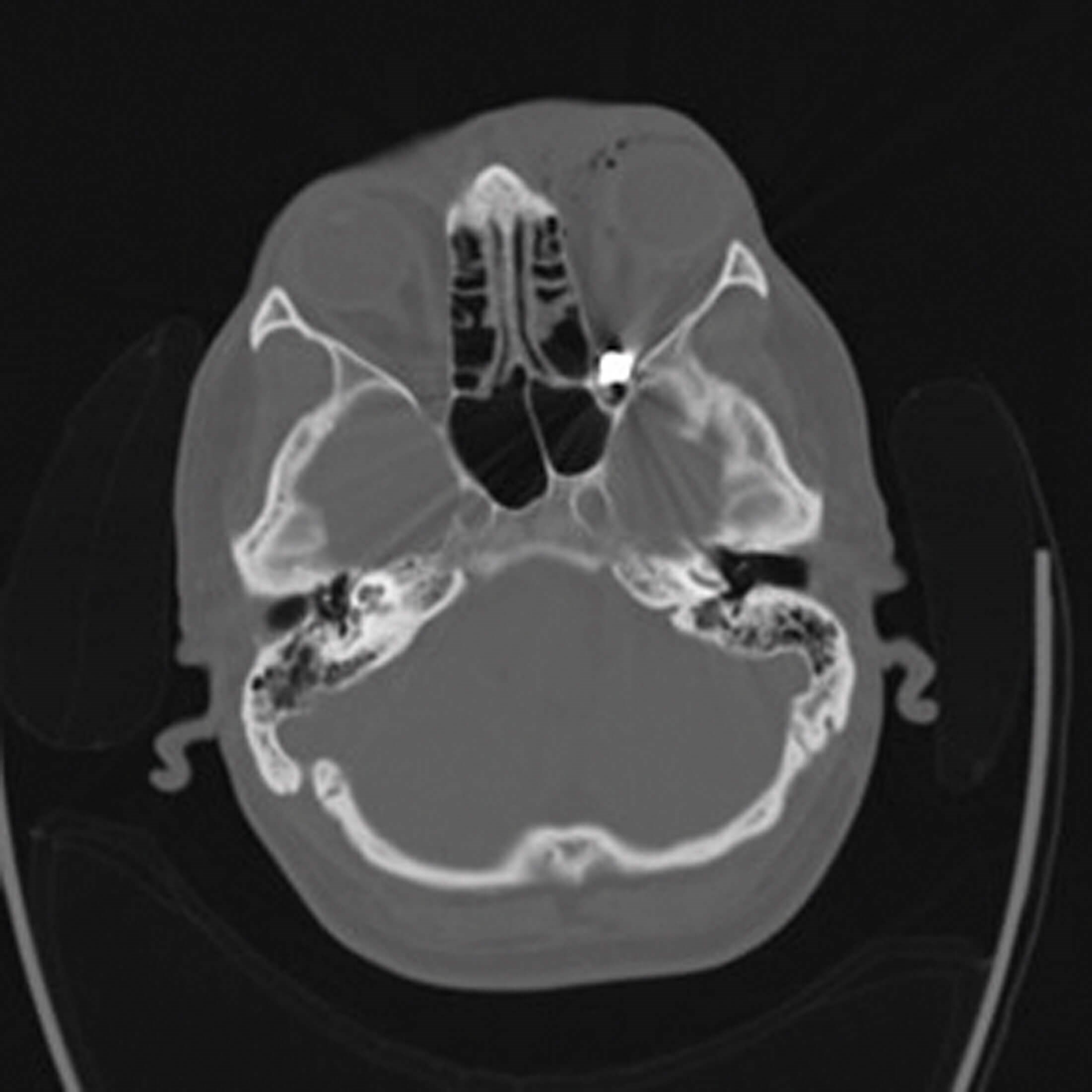

Figure 1: Computed tomography scans of the head showing the presence

of a foreign body with metal effect in the right posterior orbital fossa.

Case

A 30-year-old male presented with left periorbital bruising and a 5mm entry wound over the supraorbital ridge. Initial visual acuity was 6/9 in the right eye and 6/60 in the left eye with a left relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) and restricted gaze. Ocular examination revealed vitreous haemorrhage and subretinal haemorrhage. Computed tomography (CT) showed a metallic FB in the left orbital apex causing optic nerve compression (Figure 1). There was proptosis of the left eye. An immediate left lateral canthotomy was performed. Postoperatively, visual acuity in the left eye improved to 6/18 with full extra ocular movement. A review at 20 days postoperatively revealed no pain, no RAPD and left eye acuity of 6/12. Unfortunately, the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up and was uncontactable.

Discussion

When deciding whether to retrieve an orbital FB, one must balance the risks of retention, long-term infection, and heavy metal toxicity. Metallic intraorbital FB are usually well tolerated, although there is much debate within the literature concerning toxicity. There is no safe level of lead that is known to be without harmful effects. Lead toxicity may go unrecognised with non-specific symptoms. Diagnosis is insidious and blood levels are not an adequate estimate of the total body burden of lead [4]. Retained fragments may serve as a chronic source of exposure and contribute to long-term accumulation.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has traditionally been contraindicated in patients with suspected metallic FB due to the potential for ferrous alloys, but lead and copper are non-ferrous, though toxic. CT is the imaging mode of choice as it allows the evaluation of FB, anatomy, and displaced structures.

“Air gun eye injuries can be complex and sight-threatening. Early recognition of optic neuropathy is essential, and prompt management with a multidisciplinary approach improves patient outcomes”

Surgery is especially indicated where orbital symptoms develop such as pain, proptosis, decreased visual acuity or restricted mobility. Optic nerve compression, orbital infection, inflammation, large or sharp-edged objects, as well as inorganic material would make surgery more likely. Retained metallic FB have been associated with malignancy and there is ambiguity in the literature regarding removal [5]. The decision to remove a bullet depends on its composition, location, facilities available, skill and experience of the surgeon. The approach depends on the location and skill of the surgeon and removal can be extremely challenging. Projectiles entering the orbit have a propensity to funnel toward the orbital apex, a watershed at the borderline of interest of ophthalmologists, maxillofacial, ENT and neurosurgeons.

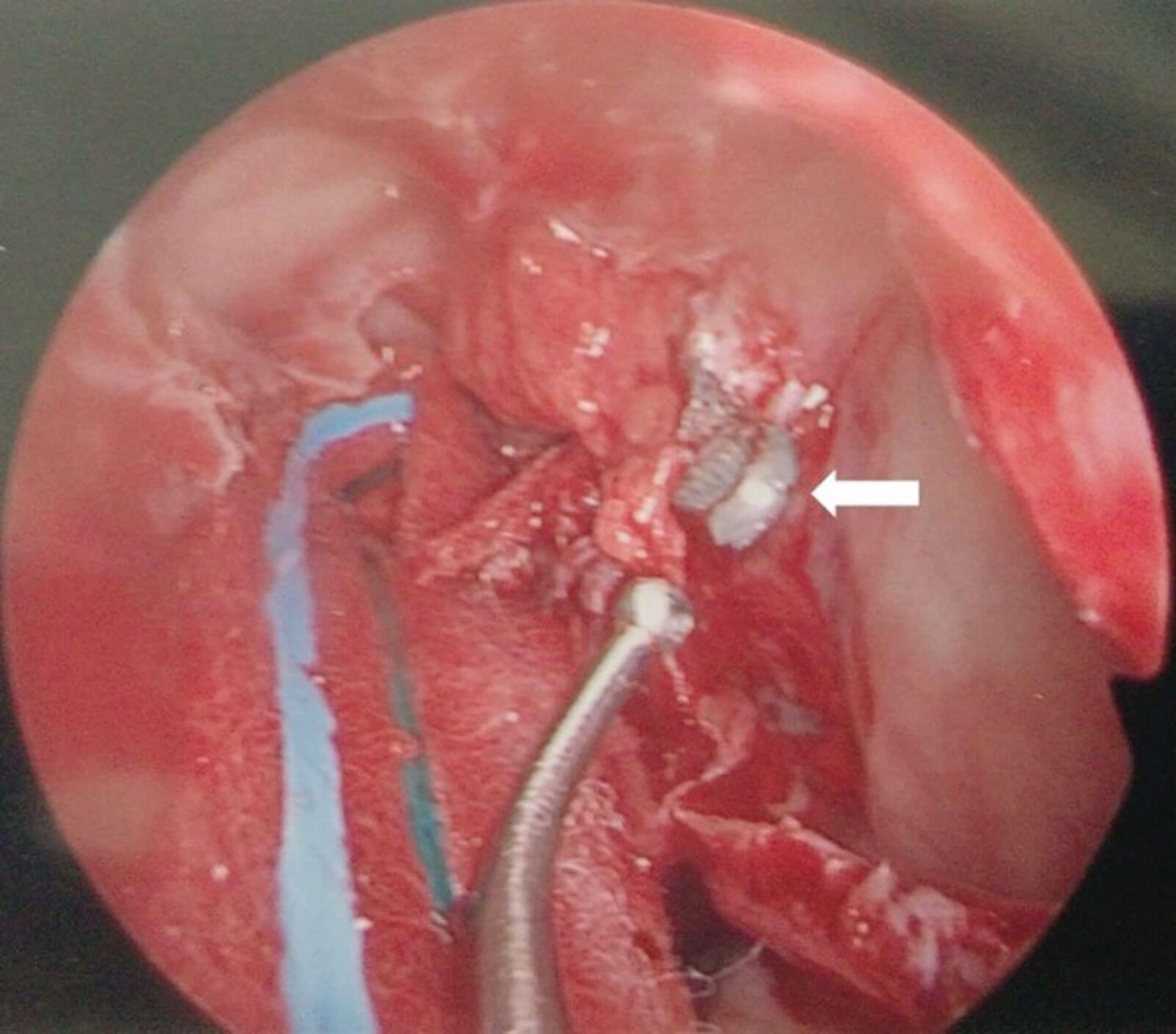

Figure 2: Left transnasal endoscopic view showing the airgun pellet located in the orbital apex.

Traditional approaches to the orbital apex are via a lateral orbitotomy however, FB within the medial intraconal space can be approached endoscopically. Retrobulbar objects pose unique surgical challenges and only a few have reported on removal using endoscopic approaches using a minimally invasive corridor to approach [6,7]. Intraconal FB are especially difficult to visualise within orbital fat and image guided navigation is essential for accurate localisation before mobilisation of orbital fat. Pellets tend to migrate whilst being manipulated during retrieval and success requires an advanced skill set (Figure 2). If ferrous, an endoscopic magnetic-assisted approach has been described [8].

Traumatic optic neuropathy has an incidence of 1.005 per million within the UK, with 13% due to assault-related causes [9]. RAPD is a reliable sign of optic neuropathy. The International Optic Nerve Trauma Study (IONTS) or subsequent studies have demonstrated a convincing functional visual benefit following treatment with steroids [10].

“Greater public awareness is required”

A collaborative, multidisciplinary approach to these challenging presentations can lead to more favourable long-term outcomes. Traditional opinion that metallic FB should be left does not address long-term risk. Early recognition of optic neuropathy and prompt surgical management by a skilled surgeon can mitigate against the harmful effects of metal toxicity.

Conclusion

Air gun eye injuries can be complex and sight-threatening. Early recognition of optic neuropathy is essential, and prompt management with a multidisciplinary approach improves patient outcomes. This case highlights the key prognostic factors predicting final visual outcome, such as the presenting visual acuity, the level of orbital and ocular trauma, monitoring of optic nerve function and timing of the surgical intervention. Greater public awareness is required to address this important eye care public health issue.

References

1. Tokdemir M, Türkçüoğlu P, Kafadar H, Türkoğlu A. Sudden death following periorbital pellet injury. Brain Inj 2007;21(9):997-9.

2. Bowen DI, Magauran DM. Ocular injuries caused by airgun pellets: an analysis of 105 cases. Br Med J 1973;1(5849):333-7.

3. Sharif KW, McGhee CNJ, Tomlinson RC. Ocular trauma caused by air-gun pellets: a ten year survey. Eye (Lond) 1990;4(6):855-60.

4. Farrell SE, Vandevander P, Schoffstall JM, Lee DC. Blood lead levels in emergency department patients with retained lead bullets and shrapnel. Acad Emerg Med 1999;6(3):208-12.

5. Kühnel TV, Tudor C, Neukam FW, et al. Air gun pellet remaining in the maxillary sinus for 50 years: a relevant risk factor for the patient? Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010;39(4):407-11.

6. Koo Ng NKF, Jaberoo MC, Pulido M, et al. Image guidance removal of a foreign body in the orbital apex. Orbit 2009;28(6):404-7. 7. Levin B, Goh ES, Ng YH, Sethi DS. Endoscopic removal of a foreign body in the orbital apex abutting the optic nerve. Singapore Med J 2019;60(5):265-6.

8. Zhao Y, Liu J, Wang Z, et al. Transnasal endoscopic retrieval of a metallic intraorbital intraconal foreign body facilitated by an intraoperative magnetic stick. J Craniofac Surg 2019;30(7):e603-5.

9. Lee V, Ford RL, Xing W, et al. Surveillance of traumatic optic neuropathy in the UK. Eye 2010;24(2):240-50.

10. Yu-Wai-Man P. Traumatic optic neuropathy-clinical features and management issues. Taiwan J Ophthalmol 2015;5(1):3-8.

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME