*Please be aware that this data does not form part of a peer reviewed research study. The information therein should not be relied upon for clinical purposes but instead used as a guide for clinical practice and reflection.

Hopefully by now you’re all familiar with the Bolam Test for clinical negligence. It dates from 1957 and dictates that no clinician can be found to be guilty of a breach of duty / negligence if they are deemed to have acted “in accordance with a responsible body of medical opinion.” We have discussed previously what a responsible body of medical opinion would look like in reality.

If 10% of doctors in the same field and level of expertise would have undertaken the same management of a patient, does that offer protection under Bolam from allegations of clinical negligence? Or if it were 1%? Or even one other competent colleague? The answer is that it is ultimately for the court to make that determination and it is not the medical expert’s role to determine breach of duty, but instead to put forth an impartial opinion as to the care of the claimant which the court may or may not accept at face value.

It is clear that Bolam historically left harmed patients vulnerable to some degree of medical protectionism. If a group of ‘bad’ doctors would have been equally bad in treating the patient in a manner which resulted in harm, then it could be argued that that would offer protection from adverse findings as a body of medical opinion would have supported that management. Since the time of Bolam, courts have refined what is deemed to be a responsible body of medical opinion and this was advanced by the case of Bolitho.

The Bolitho Test, which resulted from the 1996 court case of Bolitho versus the City and Hackney Health Authority, is an amendment to the Bolam Test and one of the most important rulings with regards to medical negligence. Although medical negligence law has evolved dramatically over time, the Bolam Test and the Bolitho Test remain vital aspects of the assessment of every case. Together they state that a doctor is not negligent if he or she acts in accordance with a responsible body of medical opinion, provided that the court finds such an opinion to be logical.

On 11 January 1984, Patrick Nigel Bolitho, a two-year-old child, was admitted to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, suffering from croup. He was seen by the senior house officer in paediatrics, as well as by the senior registrar. Neither were overly concerned by his condition, and four days later he was discharged.

The following day, however, Patrick’s condition worsened, and his parents brought him back to hospital, where he was seen again by the senior house officer in paediatrics. The doctor agreed that Patrick’s condition had deteriorated and he was readmitted. The following morning, Patrick was seen by the consultant who felt that he was much improved.

Later that afternoon, Patrick’s medical state deteriorated. A senior nurse attended him and contacted the senior paediatric registrar, asking her to come and see Patrick immediately. Hearing Patrick’s new symptoms, the senior paediatric registrar said that she would come as soon as possible. Sadly, neither she, nor the senior house officer, went to see Patrick. Another call was made to the senior registrar, however she said that she was in an afternoon clinic that she could not leave, a circumstance frequently encountered by on-call trainees even now. She stated that she had already asked the senior house officer to attend and that she would ask again. The senior house officer later testified that the batteries in her pager had run flat, so she never received these messages.

Half an hour later, Patrick collapsed. He was unable to breathe, and he suffered a respiratory and then cardiac arrest. He was revived approximately 10 minutes later, but he suffered severe brain damage. He subsequently died and his parents claimed medical negligence.

The judge presiding over the case determined that the senior paediatric registrar was in breach of her duty of care / negligent for not having attended Patrick despite receiving multiple calls from the senior nurse.

This led to a second step, however, which centred around a question of causation. The judge had to establish whether the cardiac arrest would have been avoided if the doctor had attended. This is usually described as the ‘but for’ scenario.

There was agreement that Patrick would not have suffered a cardiac arrest if he had been intubated. However, the senior paediatric registrar maintained that she would not have intubated Patrick even if she had attended him, triggering a Bolam Test of reasonableness of that proposed action, or lack thereof. The judge now had to determine whether a decision not to intubate would also have been taken by a responsible body of medical opinion.

In order to assess this, the judge heard evidence from a total of eight expert witnesses. Five of these were called on behalf of Patrick and they clearly stated that “any competent doctor would have intubated.” The other three were called on behalf of the defendant hospital and stated the opposite: “intubation would not have been appropriate.”

The judge was now faced with contradictory opinions from experts and looked back at the case of Maynard vs. West Midlands Regional Health Authority (1984). This case concerned the necessary course of action whenever two sets of expert witnesses hold diametrically opposing views. The judge in this case stated: “In the realm of diagnosis and treatment, negligence is not established by preferring one respectable body of professional opinion to another. Failure to exercise the ordinary skill of a doctor is necessary.”

In accordance with this ruling, the judge in the Bolitho case found that the senior paediatric registrar had not been guilty of negligence, since a respectable body of medical opinion (three expert witnesses) would also not have intubated Patrick.

The judgment was appealed at several levels with the argument that “the views of the defendant’s experts simply were not logical or sensible.”

When this appeal was heard in the House of Lords, the presiding Lord stated that “the court is not bound to hold that a defendant doctor escapes liability for negligent treatment or diagnosis just because he leads evidence from a number of medical experts.”

He further stated that: “The court has to be satisfied that the exponents of the body of opinion relied upon can demonstrate that such opinion has a logical basis.”

In essence, this means that while it may be possible to find a number of medical professionals who argue that they would have acted in a particular way, it is the responsibility of the court to determine whether or not that particular course of action would have been logical / sensible / evidence-based.

So, what is the relevance of all of this to the outcomes of this edition’s survey? We clearly see a minority opinion in response to several of the questions. Does that offer some protection against an allegation of medical negligence?

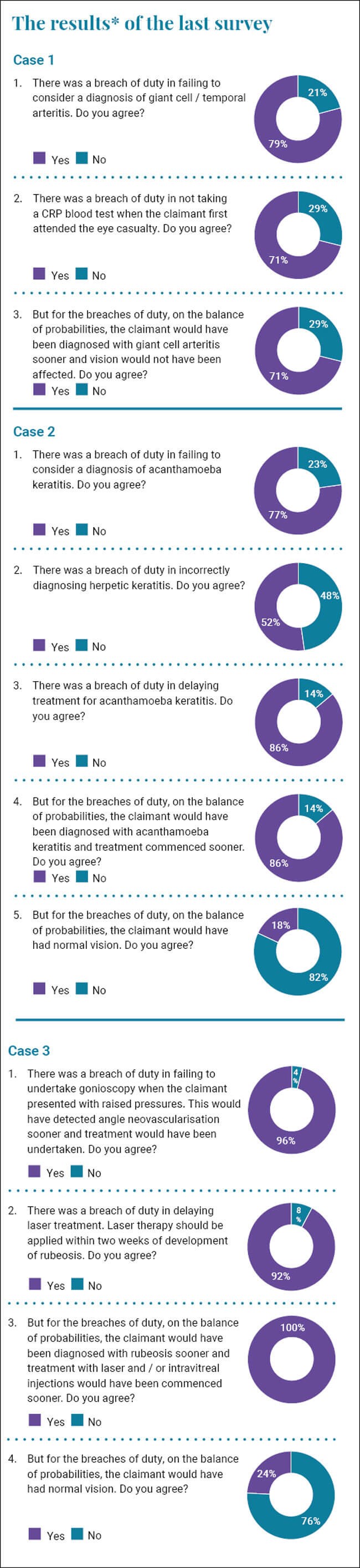

Almost 80% of respondents felt that there was a breach of duty in failing to consider the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis (GCA) while almost one in five felt that it was not a breach. Two-thirds felt it was a breach of duty not to undertake a CRP blood test and the same number feel that if the blood test had been done, the vision would have been spared.

It would seem that the court has a contrary opinion with a responsible body of medical opinion who would not have considered a diagnosis of GCA in the similar circumstances. However, does this meet the Bolitho Test? I believe that any competent ophthalmologist would have knowledge of the fact that GCA can present with fluctuating reduced vision and / or intermittent diplopia. The theoretical patient I present was of the appropriate age group. Clearly, if the patient was 40 and presented in the same way, then a diagnosis of GCA would have been extremely unlikely and therefore the balance of opinion changes.

The implications of a missed diagnosis of GCA are potentially catastrophic and blinding. The test for it is relatively cheap and easy to obtain. A reasonably competent doctor should have suspected GCA and undertaken the appropriate test and therefore I believe it was a breach of duty. As mentioned previously, it is not the expert’s role to determine this but it is the court’s decision. However, I think the counter argument that the diagnosis should not have been considered would not survive the scrutiny of the judge regarding the logic / reasonableness of it.

If my parent or your parent attended in the same circumstance and went blind because the doctor examining them did not consider the diagnosis of GCA, I think that there would be reasonable grounds for complaint, and one would expect some element of compensation. It is important to focus on the fact that all of these discussions centre around justice rather than blame after the fact, but also on prevention before the fact in the future.

In the next case scenario, two thirds of you felt that there was a breach of duty in not considering a diagnosis of acanthamoeba. I would agree with you in that it is entirely logical, sensible and appropriate to at least consider a diagnosis of acanthamoeba in a patient who wears contact lenses presenting with a red eye which does not respond to antibiotic therapy. In the vast majority of patients, it is not acanthamoeba, but it is a differential diagnosis and arguably one of the most important diagnoses to make early or definitively exclude.

There was almost a 50:50 spread in answering the next question regarding whether making a diagnosis of herpetic eye disease was a breach of duty. Making a wrong diagnosis is not a breach of duty as long as the rationale to make the diagnosis is reasonable and one that a body of medical opinion would support. Making a diagnosis of herpetic eye disease as long as the appropriate alternative diagnoses (such as acanthamoeba keratitis) were considered and excluded, even though ultimately incorrect, is not, in my opinion, a breach of duty. As previously mentioned, it will be for the court to determine this rather than the expert.

The majority of you agree that the delay to diagnosis was a breach of duty and earlier diagnosis would have meant earlier treatment. When faced with such ‘delay to diagnosis’ cases it is hard to determine when a delay turns from reasonable to a potential breach of duty. Clearly the longer the delay the more likely we are to drift into potential negligence, as we are going deeper into a timescale beyond which no reasonable doctor would have neglected the possibility of the ultimately correct diagnosis.

The last question on that case report deals with causation and loss. I agree that it is unlikely that the vision would have been normal, but it is likely that it would have been better than it was.

The responses to the final case report seem to be reasonably unanimous. We all agree that gonioscopy is vital in such cases and that laser should be done quickly when neovascularisation is detected. If we are all in agreement, then failure to undertake this gonioscopy and delays to laser should not be occurring and yet such cases are still happening. Clearly asserting that the patient would have had ‘normal’ vision is unjustified, as inevitably some visual loss would have ensued despite ‘appropriate’ treatment.

It is heart breaking to see such scenarios still happening regularly and patients coming to avoidable harm. Most importantly we need to stop our patients losing vision, but this also has a massive impact on the NHS in having to try and defend such cases and paying out significant amounts of compensation.

The final question asks how we can stop these occurrences happening again. Clearly there is no simple answer as this would have been done already. The responses focus on teaching and education, which is what I am attempting to do with this article, but how do we get appropriate penetration to the front-line clinicians who deal with these cases on a daily basis? I have been kindly invited by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists to be editor for a medico-legal section in the college’s fantastic new Inspire online learning platform. I hope that discussion of similar cases and learning points will help us all learn from errors and help keep our patients safe in the future.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME