Diabetes is rising globally, particularly in low- to middle-income countries (LMICs), where healthcare systems are under resourced [1,2]. Among its complications, diabetic retinopathy (DR) and diabetic foot disease are preventable yet frequently overlooked [3-6].

These problems often develop together due to blood vessel damage caused by prolonged hyperglycaemia. Diabetic retinopathy involves microvascular changes in the retina, while foot ulcers arise from a combination of vascular changes and peripheral neuropathy. Both complications can result in blindness or lower-limb amputation, significantly reducing patients’ quality of life [7].

In Africa, Tanzania and Eswatini often face common challenges in managing diabetes-related complications. In Tanzania’s Kigoma region, home to a population of 2.6 million, access to permanent ophthalmology and diabetes care remains limited. While in Eswatini, a country of just over one million people, struggles with a dual burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases, exacerbated by a lack of systematic diabetic eye and foot screening. This article explores two successful initiatives designed to address these challenges, highlighting achievements, barriers and recommendations for future scalability.

Methods

Two projects in Tanzania and Eswatini were developed as collaborative, multidisciplinary initiatives integrating diabetic eye and foot screening. These efforts were carried out in partnership with Queen’s University Belfast staff and local collaborators in both countries.

In Tanzania, a week-long visit to Maweni Hospital in Kigoma focused on training local staff, conducting patient screenings and facilitating follow-up treatments. Portable tools, such as the Optomed Aurora handheld camera, were used to enhance the efficiency of care delivery.

Figure 1: Diabetic eye screening in Tanzania using the Optomed camera (left) and in Eswatini (right).

In collaboration with Grace Vision in Eswatini, a foot screening approach combining the Ipswich Touch Test and the Inlow 60-second screening tool was implemented as part of a broader diabetic eye and foot health initiative funded by the World Diabetes Foundation. The Optomed Aurora handheld camera was also used to capture fundus images for DR screening. Patient education materials were co-developed with local health organisations to ensure cultural and contextual relevance.

In both countries, the UK’s NHS Grading Classification was used to grade DR severity; however, the maculopathy grading was slightly modified in accordance with the Scottish classification system to reduce unnecessary referrals to the Hospital Eye Service. Adapting classification systems to suit the local context is essential for effective and sustainable implementation.

Results

Tanzania: Diabetic eye and foot screening at Maweni Hospital, Kigoma

Kigoma’s lack of permanent ophthalmologists and endocrinologists presents significant challenges to diabetes care. In February 2024, a multidisciplinary team provided diabetes screening and treatment services at Maweni Hospital. In total, 751 patients underwent ophthalmology assessment. Immediate referrals were made for advanced care where necessary, and 14 cataract surgeries were performed. In addition, hundreds of spectacles were distributed to address refractive errors, and conditions such as glaucoma were treated.

The initiative also included diabetic foot care, with 17 patients receiving advanced wound dressings and education on foot hygiene. Local nurses were trained by the podiatrist in foot examination techniques, ensuring continuity of care after the team’s departure.

Over one week in Kigoma, 66 patients with diabetes underwent eye screening. Of the gradable images (10% ungradable); 41% had no DR; 31% had mild non-proliferative DR; 11% had moderate non-proliferative DR; and 17% had proliferative DR. Regarding maculopathy, 61% showed no signs; 19% had mild maculopathy; and 20% had referable maculopathy.

Eswatini: A scalable approach to diabetic eye and foot screening

Eswatini has a high prevalence of diabetes, yet diabetic eye and foot screening was virtually non-existent prior to 2020. A simple foot screening tool, developed through a World Diabetes Foundation-funded project, was introduced to address this gap. The tool, which requires no specialist equipment, was implemented in eye clinics, non-communicable disease clinics, and community outreach settings. Between 2020–2022, 2041 patients were screened using the tool, with around 30% found to have diabetic foot complications related to poor peripheral arterial circulation. Of these, 339 patients (16.6%) had two absent pulses (tibial and dorsal pulses) on each foot, while 259 (12.7%) had one pulse missing on each foot. Further interrogation of the data showed that patients with severe foot complications such as amputation mostly had loss of two pulses in each foot with a mean sensation score of 3/6 on the touch test.

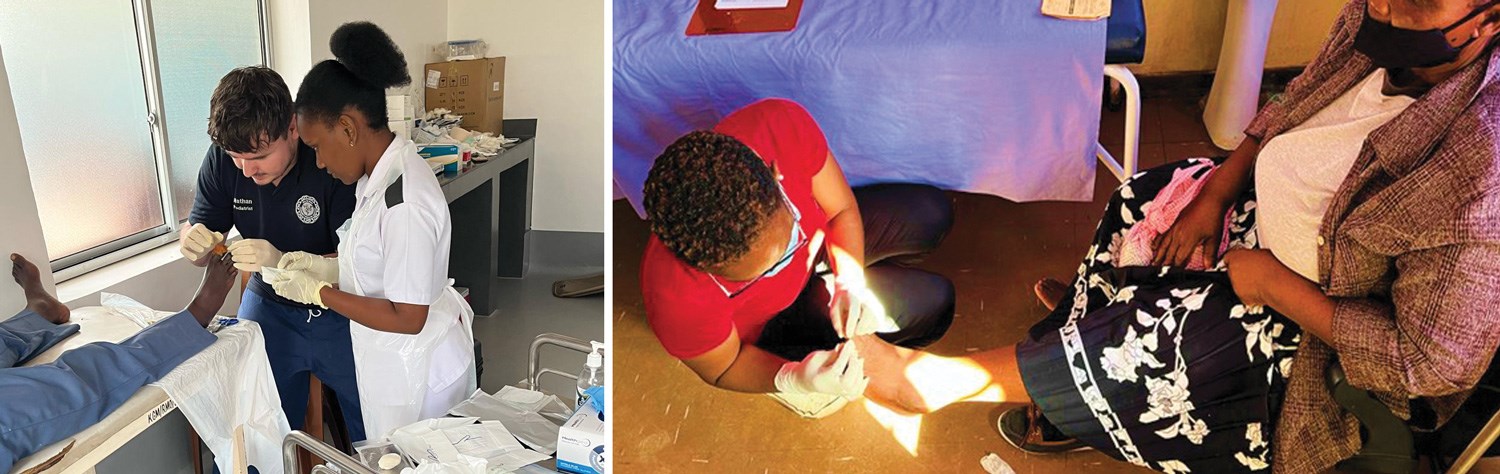

Figure 2: Foot screening in Tanzania (left) and Eswatini (right).

Figure 3: Pathology detected during foot and eye screening in Tanzania (left) and Eswatini (right).

Diabetic retinopathy severity was assessed based on the worse-affected eye. Of the 2041 participants who underwent both foot and eye assessments, 202 (9.9%) had missing DR data, and 163 (8.0%) had ungradable fundus images. Among the 1676 participants with gradable images, 1064 (63.5%) showed no signs of DR; 434 (25.9%) had mild retinopathy; 47 (2.8%) had moderate DR; and 131 (7.8%) had sight-threatening proliferative DR. Maculopathy in the worse-affected eye was also evaluated. Of the total cohort, 208 participants (10.2%) had missing data for maculopathy, and 171 (8.4%) had ungradable images. Among the 1662 participants with gradable images, 282 (17.0%) had mild maculopathy, and 71 (4.3%) had referable maculopathy.

Additionally, the project raised awareness of diabetic eye and foot complications, empowering patients to prioritise preventative care. The development of a training video during Covid-19 restrictions allowed for remote dissemination of skills, ensuring the intervention’s scalability.

Challenges and barriers

Despite these successes, both initiatives faced some challenges. Resource constraints, including limited equipment and staff shortages hindered service delivery. In Eswatini, a single government podiatrist and ophthalmologist served the entire country, emphasising the need for task-shifting to train other healthcare workers. Late presentation of patients with advanced complications, including necrotic toes and severe visual impairment (Figure 3), highlighted the urgency of improving early detection and referral systems. Staff turnover and a lack of confidence in performing screenings were additional barriers. High turnover rates among nurses in Eswatini, coupled with rotational duties, led to a loss of screening skills. These challenges underscore the importance of continuous training and quality assurance mechanisms.

Similar challenges were identified in Kigoma, Tanzania. No permanent podiatrist, ophthalmologist or endocrinologist are present, therefore task shifting and patient education are essential to improve health outcomes for people living with diabetes.

Conclusions

The findings from these initiatives demonstrate the transformative potential of simple, low-cost interventions in resource-limited settings. The use of portable tools like the Optomed Aurora cameras and a non-specialist-dependent foot screening tool highlights the feasibility of integrating such programmes into routine healthcare. Patient education emerged as a critical component of both initiatives. Empowering patients to understand and manage their diabetes complications is essential for improving health outcomes. However, systemic barriers, such as inadequate funding and infrastructure, must be addressed to ensure the sustainability and scalability of these programmes.

Future efforts should focus on incorporating eye and foot screenings into primary healthcare services, supported by training videos and standardised protocols. Implementing quality assurance measures is essential to protect patients and improve the accuracy and reliability of screenings. Awareness campaigns about diabetes complications should be prioritised to encourage early presentation. As the prevalence of diabetes continues to rise, particularly in resource-limited settings, scaling up such efforts is more urgent than ever.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the entire teams in Kigoma and Eswatini for their invaluable contributions to this project, with special acknowledgment to Nathan Gibson, Rebecca Thomas, Benedict Leonard-Hawkhead (Tanzania), Pauline Roberts and Roger Roberts (Eswatini). We extend our heartfelt gratitude to all the participants and hospital staff who supported and contributed to this work.

References

1. Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, et al. Global Prevalence of Diabetes: Estimates for the year 2000 and projection for 2030. Diabetes Care 2004;27(5):1047–53.

2. https://diabetesatlas.org/idfawp/resource-files/

2021/07/IDF_Atlas_10th_Edition_2021.pdf

3. Ting DSW, Cheung GCM, Wong TY. Diabetic retinopathy: global prevalence, major risk factors, screening practices and public health challenges: a review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2016;44(4):260–77.

4. Yau JWY, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, et al. Global Prevalence and Major Risk Factors of Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetes Care:

http://care.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/

doi/10.2337/dc11-1909

5. Hashemi H, Rezvan F, Pakzad R, et al. Global and Regional Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy; A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Global and Regional Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy ; A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Semin Ophthalmol 2022;3(37):291–306.

6. Teo ZL, Tham YC, Yu M, et al. Global Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy and Projection of Burden through 2045: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2021;128(11):1580–91.

7. Ramsey DJ, Kwan JT, Sharma A. Keeping an eye on the diabetic foot: The connection between diabetic eye disease and wound healing in the lower extremity. World J Diabetes 2022;13(12):1035–48.

[All links last accessed July 2025]