Vishal Shah walks us through his thought process whilst highlighting the importance of routine investigations when dealing with unusual retinovascular presentations.

Retinal changes can arise in anaemia, leukaemia, lymphoma, myeloproliferative and myelodysplastic syndrome. They are often the first manifestation of haematological disease and present an important diagnostic conundrum since while the changes are non-specific and rarely sight threatening, the underlying systemic disorder can be life-threatening.

Case presentation

A 68-year-old Caucasian lady attended the eye casualty having been referred by a minor eye conditions specialist (MECS) optometrist with suspected right-sided branch retinal vein occlusion. She reported a one-week history of a painless right-sided cobweb-like visual disturbance. There was a past medical history of hypothyroidism for which she was taking levothyroxine, but no diabetes or hypertension. There was a past ocular history of bilateral pseudophakia. Social history revealed her to be a retired GP receptionist, non-smoker with an average consumption of 15 units of alcohol per week.

Examination revealed best corrected visual acuities of 6/9 with pinhole in the right and 6/7.5 unaided in the left. The anterior compartment examination was unremarkable with healthy adnexae, white and quiet eyes, clear media, healthy irides, open angles, normal intraocular pressures (IOP) at 10mmHg and 11mmHg in the right and left respectively, and bilateral pseudophakia.

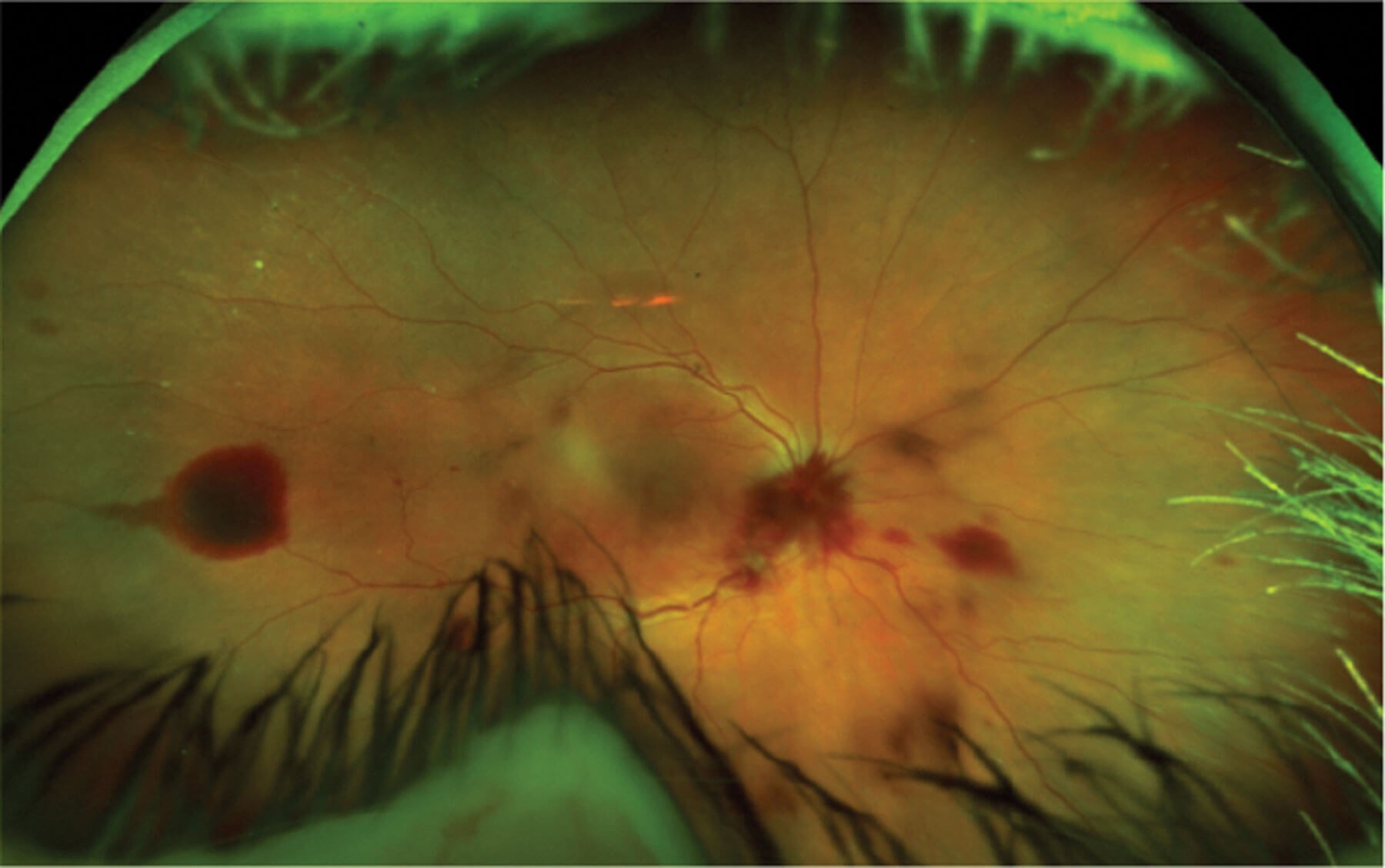

Figure 1: Widefield Optos retinal colour photography of the right eye.

Posterior segment examination revealed pre-retinal haemorrhage in the right eye that obscured much of the disc. The aspects of the disc that were visible revealed no obvious pallor or swelling. Microaneurysms were noted at the macula and multiple multi-layered haemorrhages were noted to the retinal periphery with intraretinal and pre-retinal bleeds, along with breakthrough bleeding into the vitreous cavity (Figure 1). The left eye demonstrated a pristine fundus with a pink well-perfused disc with clear margins and no cupping, a healthy macula with crisp foveal reflex and a healthy periphery with normal vasculature and no retinovascular changes, haemorrhage or exudate (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Widefield Optos retinal colour photography of the left eye.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis in this case is wide and centred on causes of retinovascular disease. At the top of my list was proliferative diabetic retinopathy with new vessels at the disc (NVD) that have bled. Against this, she was not a diabetic and the presentation was extremely asymmetric with no retinovascular changes in the fellow eye. A close second differential was ischaemic retinal vein occlusion (RVO) with NVD that has bled. Against this, she had reasonable visual acuity, no relative afferent pupil defect (RAPD), normal IOP and no neovascularisation of the iris (NVI) or neovascularisation elsewhere (NVE). Furthermore, aside from age, there were no significant risk factors for RVO and the clinical presentation did not fit, given the atypical distribution of the retinal haemorrhages, absent disc swelling and lack of cystoid macular oedema.

Other conditions further down my list of differentials were as follows: retinal artery macroaneurysm, however against this there was no history of hypertension and no exudate on examination, and ocular ischaemic syndrome, however there was no anterior chamber (AC) flare, no hypotony and the history did not suggest transient ischaemic attack (TIA).

Figure 3: OCT macula of right eye.

Figure 4: OCT macula of left eye.

Investigations and further management

Vital signs were taken and these found the patient to have a normal blood pressure at 132/73mmHg and a random blood glucose level in the normal range at 5.5mmol/l. OCT imaging was undertaken of the maculae (Figures 3 and 4) and while the view was slightly impaired by vitreous haemorrhage in the right eye, both eyes were noted to have intact retinal architecture with preserved foveal contours and no oedema to either macula.

A plan was made to work this patient up for an atypical retinal vein occlusion with screening bloods of full blood count (FBC) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and additional bloods including vitamin B12, folate, renal profile, thyroid function, lipid profile and a connective tissue diseases panel. She was also booked for urgent fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) with a plan for subsequent review in the medical retina clinic with the results.

The full blood count is shown below (Table 1), the remaining investigations came back in the normal range. The full blood count demonstrated a pancytopenia. The consultant haematologist on call was contacted immediately. They explained that the findings could represent an acute leukaemia and advised that the patient would need to come in the next day for a bone marrow biopsy. These blood test results coupled with this plan were then relayed to the patient.

In the days following on from the biopsy the patient noted a decline in her general condition with increasing breathlessness. She contacted the haematology clinical nurse specialist (CNS) who identified a further drop in haemoglobin down to 69g/L. The patient was transfused with red blood cells and with that her level increased to 83g/L. The results of the bone marrow biopsy were discussed at the haematology multisdisciplinary team (MDT) and a working diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) was made.

The patient was subsequently admitted electively for her first round of chemotherapy. During this admission she complained of generalised headaches and this led her team to arrange for computed tomography (CT) of the head. The imaging revealed bilateral acute on chronic subdural haemorrhages with no mass effect or midline shift and these were managed conservatively. The patient has since been discharged home having completed her first cycle of chemotherapy and is now undergoing preparations to receive stem cell therapy.

The FFA identified both eyes to be well perfused with no evidence of vascular occlusion or leakage. Mild masking was noted in the right eye from pre-retinal haemorrhage, and this had already reduced significantly in magnitude by the time of the FFA. The right eye is now almost entirely back to normal with a visual acuity of 6/6 and significant resolution of the retinal haemorrhages.

Introduction

Haematological disease includes any pathology that affects the haematopoietic or lymphatic systems [1]. Diagnosis is achieved via examination of the blood, bone marrow and lymph nodes [2]. Examination of the retina can reveal a range of findings such as haemorrhages, Roth spots, vessel tortuosity and cotton wool spots and such findings can thus be an important clue to underlying systemic disease [3].

Pathophysiology

Intraretinal bleeding and cotton wool spots are direct stigmata of retinal hypoxia, while vessel tortuosity is linked to dilatation caused by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) upregulation in this setting. Retinal hypoxia may be the direct result of reduced haemoglobin concentration as faced in anaemia or relate to vascular stasis as encountered in coagulopathies and myeloproliferative disease. Hypoxia of the deep capillary bed in the setting of anaemia can lead to subretinal and breakthrough bleeding into the vitreous cavity [3].

Epidemiology

Ocular involvement has been reported in 46% of cases of MDS [4]. MDS consists of clonal bone marrow diseases associated with abnormal haematopoiesis and peripheral cytopenias [5]. MDS patients have a propensity to progress to acute myeloid leukaemia, and retinal haemorrhage has been suggested as a possible prognostic factor for such progression [4]. Ocular manifestations may be even higher in leukaemia, with reports as high as 90% [6]. Leukaemia is characterised by abnormal proliferation of developing white blood cells. Acute lymphocytic leukaemia arises in the first decade while the chronic form predominates in the over 50 years age range. Acute myeloid leukaemia is commonest in the third and sixth decades of life [7].

Conclusion

Investigations prompted by the retinal examination in this case led to the identification of haematological malignancy and onward specialist referral. This ensured potentially life-saving treatment was initiated in a timely fashion and multidisciplinary input was achieved.

TAKE HOME MESSAGE

-

Haematological disease should be considered as part of the differential diagnosis whenever one is faced with unexplained retinovascular changes such as retinal bleeding or cotton wool spots.

-

The responsibility to chase investigations that you initiate lies with you.

-

Break bad news if appropriate to do so but clearly signpost the patient to the subspecialist for further questions.

-

Do not underestimate the power of the mighty full blood count; you might just save a life.

References

1. Weatherall DJ. The inherited diseases of hemoglobin are an emerging global health burden. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2010 3;115(22):4331-6.

2. Dhodapkar MV, Borrello I, Cohen AD, Stadtmauer EA. Hematologic malignancies: plasma cell disorders. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book. 2017 1;37:561-8.

3. Lang GE, Lang SJ. Ocular findings in hematological diseases. Der Ophthalmologe: Zeitschrift der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen Gesellschaft. 2011;108(10):981-3.

4. Kezuka T, Usui N, Suzuki E, et al. Ocular complications in myelodysplastic syndromes as preleukemic disorders. Jpn j Jphthalmol 2005;49(5):377-83.

5. Hasserjian RP. Myelodysplastic syndrome updated. Pathobiology. 2019;86(1):7-13.

6. Kincaid MC, Green WR. Ocular and orbital involvement in leukemia. Surv of Ophthalmol 1983;27(4):211-32.

7. Yogarajah M, Tefferi A. Leukemic transformation in myeloproliferative neoplasms: a literature review on risk, characteristics, and outcome. Mayo Clin Proc 2017;92(7):1118-28.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the patient who generously consented for their medical history and clinical experience to be written up and repurposed for this article.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME