The classification of macular holes has been modernised by OCT findings. This is a brief review and encompasses the historical literature on macular holes.

A macular hole is an anatomical discontinuation of the neurosensory retina at the centre of the macula. They are often a result of pathological vitreoretinal traction at the fovea. The formation of a macula hole often evolves over weeks to months and was famously described in stages by Gass [1]. In more recent years a new OCT based classification has been published by the International Vitreomacular Traction Study (IVTS) Group [2]. High myopia and blunt ocular trauma have also been implicated in the formation of macular holes. Epidemiological studies have shown approximately 72% of idiopathic macular holes occur in women with more than 50% of holes found in individuals aged 65 to 74 years and only 3% in those under the age of 55 [3]. There is an overall 10-15% risk of a patient with a full-thickness macular hole (FTMH) in one eye developing an FTMH in the fellow eye in five years. The risk is around 1% or less in the fellow eye if posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) is present [4].

Signs and OCT features

Stage 0: Macular holes (IVTS: vitreomacular adhesion – VMA)

This term was originally proposed to identify the OCT finding of oblique foveal vitreoretinal traction before the appearance of clinical changes.

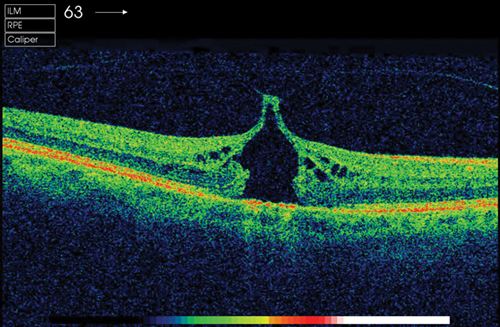

Stage 1a: ‘Impending’ macular hole (IVTS: vitreomacular traction – VMT)

This appears as a yellow spot with a flattening of the foveal depression (100-200 microns in diameter). The inner retinal layers detach from the photoreceptor layer often producing a cystic cavity.

Stage 1b: Occult macular hole (IVTS – VMT)

This is seen as a yellow ring 250-300 microns in diameter. With loss of structural support the photoreceptor layer undergoes a centrifugal displacement with a persistent adherence of the posterior hyaloid to the retina – 60% of stage 1 holes may not progress to stage 2.

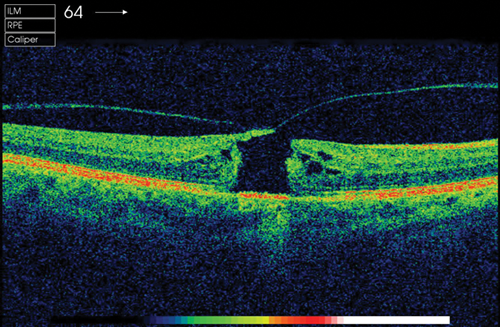

Stage 2: Small full thickness hole (IVTS: small or medium FTMH with VMT)

Consists of a FTMH less than 400 microns in diameter at its narrowest point.

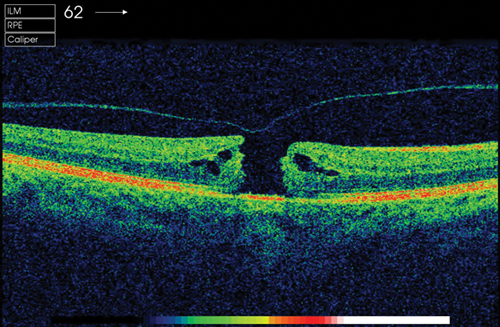

Stage 3: Full size macular hole (IVTS: medium or large FTMH with VMT)

FTMH greater than 400 microns in diameter. A grey cuff of subretinal fluid may be detected surrounding the hole. An overlying retinal operculum may be present on the posterior hyaloid overlying the hole. By definition there is persistent parafoveal attachment of the vitreous cortex.

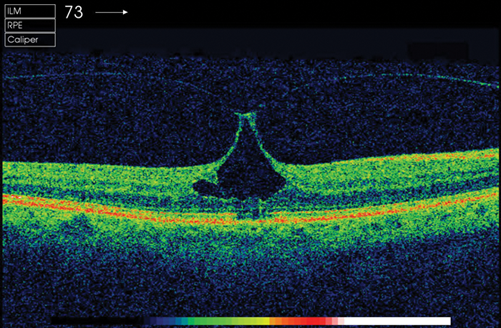

Stage 4: Full thickness macular hole with complete PVD (IVTS: small, medium or large FTMH without VMT)

FTMH where the posterior vitreous is completely detached. A Weiss ring may be present.

Figure 1: Stage 1 macular hole.

Figure 2: Stage 2 macular hole.

Figure 3: Stage 3 macular hole.

Figure 4: Stage 4 macular hole.

Evaluation

History

A thorough ophthalmic history eliciting the duration of onset of symptoms and any previous ophthalmic history. Chronicity is associated with a poorer visual outcome. Document any symptoms of distortion, anismetropia or decreased vision.

Causes of macular holes: idiopathic, trauma, cystoid macular oedema, epiretinal membrane, rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, laser injury, pathological myopia, diabetic retinopathy.

Physical examination

Slit-lamp biomioscropy of the macula and vitreoretinal interface. The Watske-Allen test is performed by projecting a narrow slit beam over the centre of the hole vertically and asking if the patient notices any thinning or breaking of the beam. Optic disc assessment is required to rule out any optic disc pits or advanced cupping. Document peripheral retinal examination to rule out any other retinal breaks or lesions.

Ancillary testing

Amsler grid testing will usually show non-specific central distortion as opposed to a scotoma. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is an extremely useful aid in the diagnosis, staging and follow-up of macula holes. OCT is adept in demonstrating the anatomy, as well as measurement of a macular hole. The presence of any over lying vitreous traction or epiretinal membrane can also be identified.

Surgical management

Preoperative discussion

It is imperative to set out the realistic goals of macular hole surgery to the patient. Particular awareness should be given to addressing the patient’s expectations. The natural history of macular hole pathology if left untreated should be explained with a likely result of poor central visual acuity with normal peripheral vision. Any delays in repair may impede the success of anatomical closure. The need for future surgery relating to any cataract which develop or retinal breaks should be explained.

The type of anaesthesia required should be explained to the patient. Usually local anaesthesia is sufficient with general anaesthesia being reserved for patient dependent factors such as claustrophobia or inability to lie flat.

The need for an intraocular tamponade with postoperative posturing should be discussed with the patient. Their ability and willingness to posture should be elicited with the appropriate duration of posturing mentioned. The surgeon should highlight the risk of intraocular pressure rising with the tamponade in place and for those patients with glaucoma an adequate pressuring lowering medication prescribed.

Vitrectomy

The goal of the pars plana vitrectomy in this instance is to separate the posterior hyaloid from the retinal surface. This may be aided after core vitrectomy with the injection of Triamcinolone Acetate to highlight the posterior hyaloid and successfully create a posterior vitreous detachment. Awareness of creating retinal breaks during this process should be paramount in the surgeon’s mind.

ILM peeling and dyes

The internal limiting membrane (ILM) acts as a cellular scaffold for the proliferation of contractile tissue involved in vitreomacular traction. Therefore, failure of the original surgery or subsequent reopening of closed holes may occur if the ILM is not removed. Some studies have shown a large difference in anatomical success rate favouring ILM peeling [5] (84% vs. 48%) in anatomical hole closure.

Indocyanine Green (ICG), Trypan Blue (TB) and Brilliant Blue (BB) have all been used to help visualise the ILM. A meta-analysis concluded there is no difference in the rate of macular hole closure between eyes that had ILM peels without dyes or with the assistance of ICG or BB [6]. The literature reveals no definitive conclusion on which dye is the best to use and it is largely surgeon dependant on which dye is favoured. If the surgeon favours ICG then the lowest concentration of ICG should ideally be used <0.05%.

Tamponades

Retinal tamponade may be created by the injection of various agents to assist with the anatomical closure at the end of macular hole surgery. Commonly used agents include air which dissipates in days, short acting gases such as SF6 (two to four weeks), medium acting gases such as C2F6 (three to six weeks) and longer acting gases such as C3F8 (six to ten weeks). In general, there is no overall consensus to which gas is the best to use. Larger chronic holes may require longer acting gases to give the best outcomes. In most cases of gas tamponade the patient is required to posture postoperatively either prone or facedown to assist tamponade of the retina.

The optimal duration of postoperative posturing is also debated, with some studies showing excellent results with one to three days of posturing [7]. This contrasts to the early days of macular hole surgery where 14 days of facedown posturing was advised. Other studies reveal similar outcomes with no posturing at all compared with 14 days of posturing [8]. There once again is no consensus over the optimal duration of posturing or if it is required. Some surgeons only posture in holes greater than 400 microns.

Complications

Cataract

The vast majority (80%) of phakic patients undergoing vitrectomy will develop a visually significant cataract in two years [9]. The risk of closed macular holes reopening following cataract surgery was shown to be increased up to sevenfold if macular oedema develops post cataract surgery [10]. Therefore, some surgeons advocate a combined procedure. The risks of combining vitrectomy with phacoemulsification include hypotony, postoperative fibrinous uveitis, iris-lens capture and macular oedema.

Retinal detachment

Studies report an incidence of 1-5% of postoperative retinal detachment following macular hole surgery [11]. The detachment is most often located inferiorly with a flap tear of the posterior vitreous base.

Endophthalmitis

Endophthalmitis has been reported to occur in less than 0.05% of vitrectomies performed for macular hole surgery [12].

Gas related complications

Air travel and high altitudes must be avoided by patients with intravitreal gas bubbles until complete dissipation has occurred. Expansive elements of the gas may cause intraocular pressure to rise and arterial occlusion to occur along with wound dehiscence or gas leakage. Most surgeons advocate the patient wearing a wrist band stating that the eye contains intraocular gas. This is important as nitrous oxide anaesthesia or gasses can cause gas bubble expansion and should be avoided.

Outcomes

Overall surgical closure rates have been reported from 91-98% with the mean postoperative visual acuity being 20/40 [13]. This is certainly better than the final acuity of an untreated macular hole. Patients who do not achieve primary hole closure tend to have less benefit from subsequent surgery. The consensus of the vitreoretinal community is to recommend surgery for stage 2 macular holes as the visual acuity results are good with surgery and it prevents further vision loss associated with stage 3 and 4 macular holes.

Conclusion

Modern day macular hole surgery provides a good treatment option for a disease that 30 years ago was deemed incurable. Advances in technology and surgical practice have enabled a relatively safe and effective operation with high rates of anatomical closure achieved.

References

1. Gass JD. Idiopathic senile macular hole. Its early stages and pathogenesis. Arch Ophthalmol 1988;106:629-39.

2. Duker JS, Kaiser PK, Binder S, et al. The International Vitreomacular Traction Study Group classification of vitreomacualr adhesion, traction and macular hole. Ophthalmology 2013;120:2611-9.

3. Eye Disease Case-Control Study Group. Risk factors for idiopathic macular holes. Am J Ophthalmol 1994;118:754-61.

4. Ezra E, Wells JA, Gray RH, et al. Incidence of idiopathic full-thickness macular holes in fellow eyes. A 5-year prospective natural history study. Ophthalmology 1998;105:353-9.

5. Lois N, Burr J, Norrie J, et al. Internal limiting membrane peeling versus no peeling for idiopathic full-thickness macular hole: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:1586-92.

6. Benson WE, Cruickshanks KC, Fong DS, et al. Surgical management of macular holes: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2001;108:1328-35.

7. Dhawahir-Scala FE, Maino A, Saha K, et al. To posture or not to posture after macular hole surgery. Retina 2008;28:60-5.

8. Tranos PG, Peter NM, Nath R, et al. Macular hole surgery without prone positioning. Eye 2007;21:802-6.

9. Passemard M, Yakoubi Y, Muselier A, et al. Long-term outcome of idiopathic macular hole surgery. Am J Ophthalmol 2010;149:120-6.

10. Bhatnagar P, Kaiser PK, Smith SD, et al. Reopening of previously closed macular holes after cataract extraction. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;144:252-9.

11. Banker AS, Freeman WR, Kim JW, et al, Vitrectomy for Macular Hole Study Group. Vision-threatening complications of surgery for full-thickness macular holes. Ophthalmology 1997;104:1442-52, discussion 1452-3.

12. Park SS, Marcus DM, Duker JS, et al. Posterior segment complications after vitrectomy for macular hole. Ophthalmology 1995;102:775-81.

13. Tadayoni R, Vicaut E, Devin F, et al. A randomized controlled trial of alleviated positioning after small macular hole surgery. Ophthalmology 2011;118:150-5.

14. American Academy of Ophthalmology Retina/Vitreous Panel. Preferred Practice Pattern®Guidelines. Idiopathic Macular Hole. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2014.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME