A 79-year-old male presented to the ophthalmic emergency department with a three week history of left eye pain. He also reported visual deterioration in the left eye over the same period. He suffered from degenerative myopia, with his spectacle prescription being -19.00/+1.00 x 90 in the right eye and -19.00/+1.00 x 75 in the left. His medical history was unremarkable apart from premature birth. He had never undergone any ocular surgical or laser intervention.

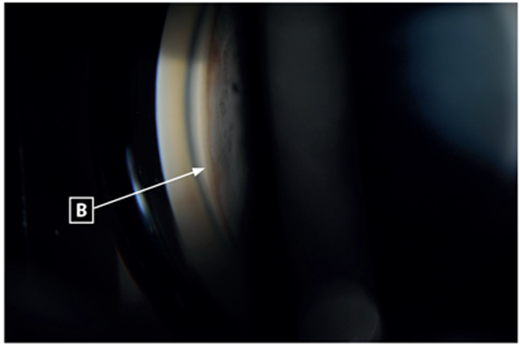

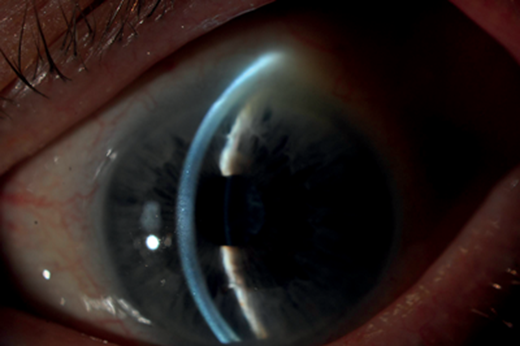

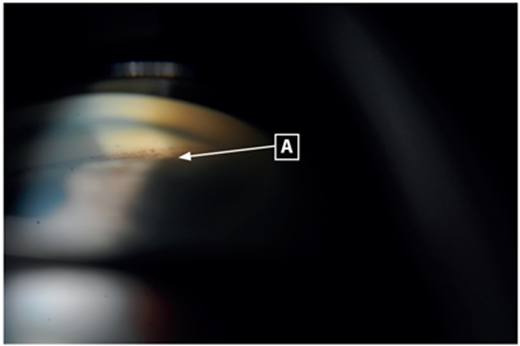

On examination, visual acuity was 6/96 in the right eye and 6/192 in the left eye. Intraocular pressures measured 11mmHg in the right eye and 40mmHg in the left. The left eye was injected, with a mid-dilated, non-reactive pupil and the cornea was cloudy. The anterior chamber appeared shallow in both eyes and there was cataract present in both eyes (nuclear sclerosis) (Figure 1). Gonioscopy revealed no visible angle structures in both eyes (Shaffer grade 0), with the left eye demonstrating extensive peripheral anterior synechiae and the right eye demonstrating appositional closure (Figures 2 and 3). There was no evidence of neovascularisation of the anterior segment.

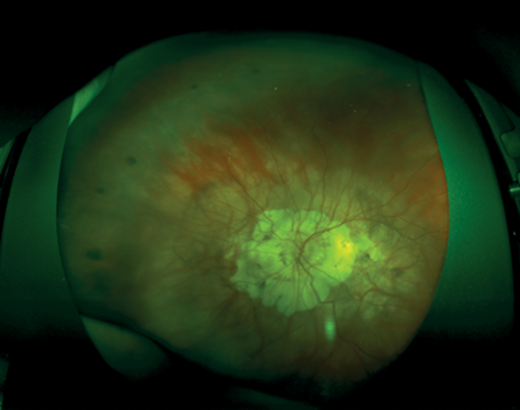

Fundus examination demonstrated bilateral myopic macular degeneration. There was extensive peri-papillary atrophy and thin optic nerve neuro-retinal rims in both eyes (Figure 4).

Biometry demonstrated axial lengths of 30.02mm in the right eye and 30.09mm in the left eye. Keratometry was 7.91mm/7.69mm x 58 degrees in the right eye and 7.80mm/7.69mm x 48 degrees in the left eye. Anterior chamber depth was 2.26mm in the right eye and 2.31mm in the left eye.

Figure 1: Slit-lamp anterior chamber photograph of left eye showing deep anterior chamber and nuclear sclerosis.

Figures 2 and 3: Gonioscopy revealed no visible angle structures in both eyes (Shaffer grade 0), the left eye demonstrating extensive peripheral anterior synechiae and the right eye demonstrating appositional closure. A: pigment above Schwalbe’s line from previous appositional closure, now synechial closure in left eye. B: indentation gonioscopy of right eye demonstrating angle opening to reveal trabecular meshwork.

Figure 4: Wide-field fundus image of the left eye. Typical myopic fundus with extensive peripapillary atrophy.

Questions

-

What is the diagnosis?

-

What are the causes and mechanisms of angle closure in patients with myopia?

-

What are some diagnoses present in myopic patients that develop angle closure glaucoma?

-

What is the treatment?

References

1. Barkana Y, Shihadeh W, Oliveira C, et al. Angle closure in highly myopic eyes. Ophthalmology 2006;113(2):247-54.

2. Michael AJ, Pesin SR, Katz LJ, Tasman WS. Management of late-onset angle-closure glaucoma associated with retinopathy of prematurity. Ophthalmology 1991;98(7):1093-8.

Answers

1. The patient has angle closure glaucoma of the left eye, but has high (axial) myopia. This is a relatively rare condition. Most commonly, the refractive error in patients with angle closure glaucoma is hypermetropia. There is also a tendency towards shorter axial lengths, smaller anterior chamber depths and thicker lenses in these patients.

2. Relative pupillary block may be the mechanism of angle closure in patients with high myopia, however, it tends to be less common compared with the rest of angle closure cases. Those who do have relative pupillary block as the mechanism usually have non-axial myopia. For example, patients with corneal myopia (e.g. keratoconus) or lenticular myopia, can develop angle closure from increasing antero-posterior lens thickness, but have normal or shorter axial lengths. Also, patients with retinopathy of prematurity may develop early or late onset angle closure due to pupillary block from anterior displacement of the lens-iris diaphragm secondary to contraction of a retrolental fibroglial mass or from an increased ratio of the thickness of the lens to the axial length of the eye [1]. Lens-related causes may contribute to a mechanical narrowing of the angle (with concomitant lenticular myopia), e.g. anteriorly displaced lens in Weill-Marchesani syndrome or ectopia lentis. Plateau iris configuration, with anterior rotation of the ciliary body forcing the peripheral iris into the angle, may be present in patients with myopia, as a mechanism of angle closure rather than pupillary block. Secondary angle-closure mechanisms such as cicatricial pupillary membranes causing secondary pupil block, neovascularisation of the angle or anterior rotation of the ciliary body may be present in patients with retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) who are also very likely to have high myopia. They can also develop relative pupillary block or have lens-related mechanical narrowing of the angle. It has been proposed that hypoxia of peripheral retina inhibits the normal growth of the ciliary body and zonules, resulting in a mismatch with the lens size and the anterior segment depth [2]. Due to the patient’s significant peripheral retinal degenerative changes, a demarcation line or ridge could not be identified in the peripheral retina. However, in view of the history of prematurity and the anterior segment findings, angle closure with a background of ROP was considered as the most likely cause. The proposed angle closure mechanism is relative pupillary block, with shorter anterior chamber depth and increased lens thickness with progressive synechial formation.

3. Retinopathy of prematurity, cataract, Weill-Marchesani syndrome, ectopia lentis, microspherophakia, Marfan’s syndrome, Plateau Iris syndrome, aqueous misdirection.

4. Careful assessment of the mechanism of the angle closure glaucoma is critical, with gonioscopy, refraction, biometry, ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) and anterior segment optical coherence tomography (OCT) an essential part of the work-up. This is especially so, as miotics can make angle closure glaucoma worse in those with lens-related angle closure mechanisms. Pupil block mechanisms will benefit from a laser peripheral iridotomy. Indentation gonioscopy can help to determine whether the angle is reversibly closed (appositional closure) or irreversibly closed (synechial closure). Generally a laser peripheral iridotomy will reduce the intraocular pressure better in appositional angle closure rather than synechial closure. This patient had peripheral iridotomies performed after medical treatment had been instituted. Iridotomy widened the angle in his right eye, but there was no change in the angle configuration of the left eye due to extensive peripheral synechiae. Despite iridotomy, the intraocular pressure remained at 38 and combined with the higher risks of cataract surgery with longer axial length (>30mm) and poor visual potential given the myopic macula degeneration, a cycloablation procedure was performed, rather than cataract extraction surgery. This reduced his intraocular pressure to 13mmHg in the left eye on only one intraocular-pressure lowering drop. Patients with suspected plateau iris configuration should have UBM to confirm the diagnosis, and consideration for argon laser peripheral iridoplasty. Lens-related angle closure mechanisms would benefit from pupillary dilatation and consideration for cataract extraction surgery and / or referral to vitreoretinal colleagues. According to the severity of glaucoma, treatment may also involve glaucoma filtration surgery by means of trabeculectomy or tube insertion [1,2].

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME