“What gets us into trouble is not what we don’t know. It’s what we know for sure that just ain’t so.”

The above is a quote attributed to Mark Twain from the 2006 documentary, An Inconvenient Truth, which follows Al Gore, the former Vice President of the United States, as he lectures to the public about the dangers of climate change. With regards to the NHS, we know for sure that it will always be our saviour, but I fear this is a misconception and isn’t the case for reasons which I shall explain.

From what I have observed during almost 30 years of working in the NHS, the inconvenient truth is that sadly for many reasons the NHS appears to be dying. I feel I am looking at a set of deranged liver function tests and hoping the situation is not terminal.

The NHS was established by Labour’s Minister for Health, Aneurin Bevan, on 5 July 1948 and is funded by taxation. It provides free healthcare at the point of delivery to all UK residents. It’s a true behemoth as the 9th largest employer in the world with 1.7 million employees (2015) and has an annual budget of £190.3 billion (2022). It’s also part of the national psyche and cherished by the population. In April 2022 the NHS topped the poll at 62% when the market research company, Ipsos MORI, asked the public what made them most proud to be British.

However, there are signs that the public may be falling out of love with the NHS at a time when it’s under more pressure than ever since its inception, with long waiting lists and growing staff shortages. Existing NHS staff are suffering from even higher levels of stress and burnout from excessive workloads. So where did it all go ‘Pete Tong’? Obviously, the staff are key to any organisation’s success, so let’s delve further in.

Andrew: “You work under me and Claire. We all work under two Consultants: Dr Turner and Dr Yates.”

Phil: “So who is the chap doing that Venflon for me?”

Dr Yates: “Yates is my name, but you can call me sir. No, no seriously, if you have any worries, you can call on me day or night, this is on 24 hours a day. Alright?”

Claire: “Unfortunately it’s people like him that take their bleeps to an early grave.”

In this scene from medical drama Cardiac Arrest, the Senior House Officers Andrew and Claire introduce the new House Officer Phil to the hierarchy of their team, demonstrating succinctly a few of the doctors I have met during my career who are so imbued with altruism they sacrifice themselves on the altar of the NHS.

The problem with this altruism, a selfless concern for the well-being of others, is that the running of the NHS machine relies heavily on it from its staff. This altruistic idealism is already instilled in the vast majority of sixth form students I’ve witnessed, when they enthusiastically attend their medical student interviews locally in Edinburgh. Indeed, pretty much everyone who embarks on a career in the NHS has an overwhelming desire to care for others.

The issue is that during training and postgraduate careers, the pressures of working in the NHS, and the underlying feeling of being taken advantage of, takes its toll and the altruism starts to wane. It’s not that doctors or nurses stop caring, but they become more aware of the importance of self-preservation [1].

This leads me onto the next piece of advice from my hidden curriculum, which came from one of the registrar’s in Glasgow who took me aside one day when I was looking stressed and drained in a busy eye casualty clinic. “Look after number one, because no one else will. No one will build a statue of you in appreciation of your hard work and dedication. Remember to try and take regular breaks and pace yourself.” Therefore, to mitigate against the potential chronic stress and burnout as a healthcare professional, it’s important to look after numero uno.

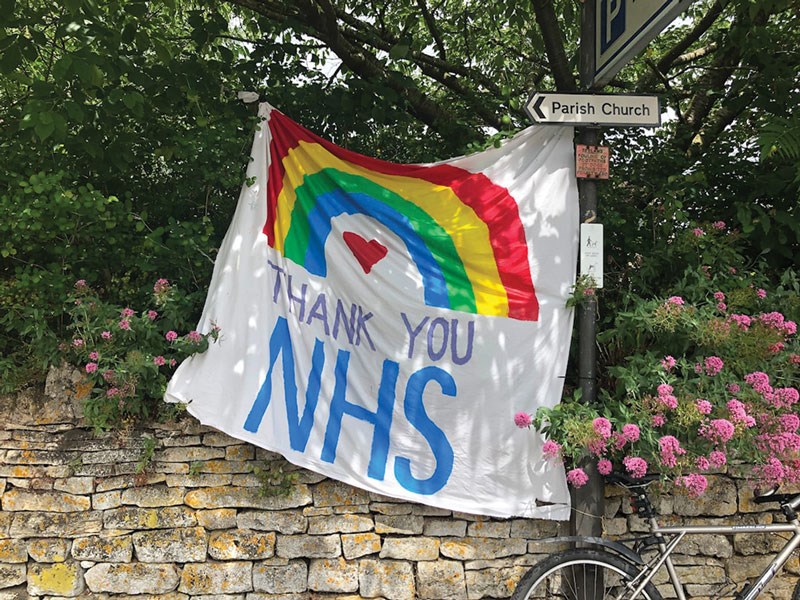

As mentioned above, there are a few members of staff that are so altruistic towards the NHS they devote their lives, to the detriment of everything else. However, for the remainder, altruism will only get you so far. So, what are the other motivating and indeed demotivating factors for any employees? There are many, but one of the most important is the financial reward, money. As Gordon Gekko says in Wall Street (1987): “What’s worth doing is worth doing for money.” However, since 2008-2009, nurses have seen a reduction in their salaries in real terms by at least 20%, junior doctors by 26%, and consultants by nearly 35%. Therefore, the message being conveyed to all NHS staff is that the work they provide is valued significantly less than it was over a decade ago. Whilst the public clapped and banged on pots and pans at 8:00pm every Thursday at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, showing love for the NHS and its staff, this was very short lived and now long forgotten. Whilst it was appreciated, it was not the reward that most staff would have wanted, which was at the very least salary parity with 2008-2009. This progressive salary reduction is a significant demotivating factor for NHS staff. There is also the fear that over time this salary erosion will drive away the talented workforce to pastures new.

“Men? Yes, er… men are here. Men are work… You work, men!”

Manuel, in this scene from Fawlty Towers, has been left in charge at the hotel reception and is speaking on the telephone to his boss, Basil Fawlty. Simultaneously, he is directing the builder, O’Reilly, and his men in their works, shortly before being punched for his efforts. In a similar fashion post-pandemic, NHS staff are being directed by their managers to work harder with increased efficiency to cope with long waiting lists which are being nudged even higher by multiple factors, including an ageing population and workforce problems caused by high sick rates, early retirements, relocations overseas in search of better pay and conditions, and increased difficulty in recruitment. The problem is that there are few incentives for higher NHS productivity, especially on a background of progressively lower salaries.

And now I need to bring up the perks of working in the NHS. Well, there aren’t any, apart from the NHS pension, but even this has seen its value gradually eroded. When I started out as a newly qualified doctor almost 30 years ago, we would joke in the doctors’ mess that our hourly rate was less than what we would earn flipping burgers in the local McDonalds. However, we looked around and thought, just like the advert for Orange mobile phones, “the future is bright!” Yes, the work was hard and intense, but observing the lifestyles of the consultants at the time and the prospects in store for us, both in financial terms and work-life balance, all seemed good and tangible. This isn’t how it turned out for my generation though and has left many feeling slightly disillusioned.

There were some perks at the time to counterbalance the poor pay and long hours. Active doctor’s messes with bars and regular parties, free onsite junior doctors’ residences, and on-call rooms were the norm, but in many places these have subsequently fallen by the wayside. Onsite staff facilities now appear to be in decline and are not deemed a priority. In my own hospital, there used to be a canteen providing hot food in the basement where all staff could gather to socialise and dine. This closed many years ago and the space is now used to store patient case notes. Staff now eat separately in their own rooms or offices with a consequent decline in socialising and camaraderie. All of this has a combined effect of lowering morale.

The UK press also needs to take some blame for battering NHS staff morale. Despite the enormous amount of good work performed by the NHS and the abundant success stories, the number of negative stories in the media vastly outweigh the positive. It seems to be a national press sport to vilify and shout from the rooftops about doctors who have been struck off by the General Medical Council rather than publicise the number of lives saved in our A&E departments every day. However, the press is in the business of selling newspapers and it seems these NHS-bashing articles are ironically what the public want.

“How dare you?” Greta Thunberg once said to the UN in a passionate speech criticising inaction over climate change. And at the risk of being mocked for following her lead I say to the British Government and recent successive Secretaries of State for Health and Social Care, “How dare you? How dare you allow the decline of the NHS and the demoralisation of its workforce to happen under your watch?” The public demands and deserves better.

However, I do not believe this is the time for political point scoring. If this situation is to be salvaged, then united cross-party discussions need to be held to establish the best way forward. In my honest opinion, the best place to start would be to address the disillusioned and demoralised NHS staff and make their lot in life better.

A recent British Social Attitudes survey showed that the overwhelming majority of people agreed that the NHS should be available to everyone (84%), should be funded through taxes (86%), and should be free of charge when needed (94%). A Health Foundation survey found that the majority of people believe that “the NHS is crucial to British society and we must do everything to maintain it”. It’s clear that the public doesn’t want change. However, from what I have seen, just like the call to arms against climate change, prompt action is needed to preserve the NHS for future generations before it’s too late. The future hangs in the balance, and I will round off with a quote by Russian author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn which comes to mind when I think of the behaviour of successive governments in recent history towards the NHS and their disconnect between words and actions:

“We know they are lying, they know they are lying, they know we know they are lying, we know they know we know they are lying, but they are still lying.”

Reference

1. Maybe this is the Self-Preservation Society referred to in the song of the same name from the famous comedy caper film The Italian Job (1969). However, I wouldn’t know as I don’t understand the context of the rest of the lyrics for example: “Babadab-babadabadab-bab-ba Jump in the jam jar gonna get straight”.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME