Meriam Islam reminds us of the importance of ‘putting our oxygen mask on first’ and avoiding burnout while we progress through our careers.

Burnout. It’s a term we hear a lot. What does it mean though? According to Merriam Webster, burnout is ‘exhaustion of physical or emotional strength or motivation usually as a result of prolonged stress or frustration’.

Though a career in medicine can be enormously rewarding, it can also be incredibly challenging. The nature of our day-to-day work results in being placed in highly pressurised environments that can build both acute and chronic levels of stress. The lack of autonomy can chip away at mental wellbeing, and sometimes all you want to do is get through the day.

This isn’t new. We have heard about burnout throughout our medical training, as if it was an inevitability that you need to either keep at bay, prepare for, or adapt to. The British Medical Association (BMA) has long recognised this issue, and in 2017 acknowledged that the mental ill health of NHS staff is a major issue resulting in presenteeism, absenteeism and poor workforce retention [1]. The feeling is ubiquitous, and yet few doctors are on long-term sick leave due to stress, and if they are, face barriers returning to work due to the associated stigma [2].

Psychological resilience is something that seems to only really crop up for other clinicians to comment on, on e-portfolio assessments or in the context of a webinar – this should not be the case – we should all be cognisant of our own psychological resilience.

So, are you burned out? Reading the above definition, I could say from one day to the next I could easily fall into this category. Is burnout a fluctuating state? If someone directly asked me if I was burned out, I would flatly deny it, but the reality is I think we are all burned out to some degree. What can we do about it?

1. Recognise and accept

A cross-sectional study of all medical doctors in the UK in 2018 found that 31.5% of doctors had high burnout scores and that generally, surgical specialties scored higher for resilience than non-surgical specialties, and foundation doctors, specialty doctors and associate specialist grade doctors had lower resilience scores than specialty trainees and consultants [3]. This is hardly surprising. Burnout has been linked to cataract surgery and is particularly high amongst UK surgical trainees across all specialties, the problem being that you have to identify that you are burnt out in order to seek help [4,5].

2. Address the problem

Health Education England describes resilience as ‘the ability to bounce back – a capacity to absorb negative conditions, integrate them in meaningful ways, and move forward.’ [6]. It is argued in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) that ‘absorbing’ any ‘negative conditions’ makes resilience a dirty word [7]. It suggests that the responsibility of our struggles lies with us alone and minimises the felt impact from our profession – dealing with responsibility, risk, uncertainty and self-doubt – ignoring the fault in poorly structured systems that are understaffed and underfunded. It is important to remember that it is okay to not feel resilient.

Placing the onus on doctors can feel unfair – yet another training module that requires completion, and the responsibility of your mental health lies on you alone. This is not true, although you should feel empowered that you can implement behavioural changes to protect your own mental health and career longevity. It is an oversimplification to assume that should doctors only have more resilience, the problem would be fixed. How are we expected to recover from our daily emotional stresses when we expose ourselves to it over and over again, in a system that is buckling under the weight of its demand? How can we help ourselves?

3. Set better boundaries at work

Setting boundaries is a kindness. It takes a lot of courage to tell people what you need and most of us are not good at vocalising what makes us feel respected and valued. Boundaries can be intimidating, but all they consist of are simple expectations and needs that help us feel safe and comfortable in relationships – work is a relationship. Employers set their boundaries in the job description (when you start and finish, the amount of annual leave you get, etc.). Work boundaries need to be a two-way street and the short-term discomfort of having this conversation is worth it.

Identify the boundaries you need to set. You can tell a colleague what hours you are and are not available to work, that you need to leave promptly on time to collect your children or that you prefer speaking on the phone rather than emailing or explicitly state how you like feedback (e.g. you prefer having written feedback so you can digest it). Think about how and when to do this. Boundaries are the rules of your relationship with work, and you need to set them early.

Our task lists can feel endless. Break free from overload and know when to decline audits or collaborative projects that you simply cannot juggle. Even when given the choice not to participate, people still take on more projects. We are so eager to join in and burn up our time on projects which may run better with fewer people. Our drive to achieve and help others is integral to our identity, and an essential component to us being where we are now as clinicians in a high-achieving specialty. The issue is that this can be an addictive cycle and you can end up overwhelmed. Naturally, fear is a major driver. The fear of missing out on opportunities or losing control sentences you to a life of doing everything yourself. The knee-jerk response can be to say yes so everyone can see how responsive you are, but sadly these fears drive us to make unproductive choices and lead us toward burnout.

Learn to be comfortable saying no. Your answer needn’t be binary, and chances are the person asking for help has no clue about what you’re juggling. Be clear about the other deadlines you have and if you don’t have the bandwidth to do what they are asking, suggest that you can show them how to do it, or just simply decline. You can also delegate tasks away that don’t require your presence. Be intentional in crafting your work life, think about your priorities a week ahead and on a two- to three-month timeline. You are the only one who knows all your goals and obligations, and you often have more of a choice than you think.

Stick to the boundaries you set. If you say you can’t stay late, do not stay late. If you stay late because a clinic is overbooked, address this later and insist that the clinic profile is revisited and discuss this with your colleagues. This is your permanant job, so you cannot be dealing with overbooked clinics daily – there will always be more patients on the waiting list but if you burn out, you help no one. Put your own oxygen mask on first. When you break these boundaries, you are teaching others that the boundary is not real and can be violated.

Consistency is key and you must restate your boundaries if needed. The more you do this, the easier it gets. If you consistently implement your boundaries, others will too. You may be the spark that ignites others to set boundaries, even if they do not have the courage to do it right away – the seed has been planted in their minds and this can be incredibly inspiring.

Finally, take every single day of paid annual leave, you have earned it and you need rest.

4. Acknowledge that anxiety can be your friend

We all feel it at various points in our lives. Anxiety has a bad rap. But there are healthy and unhealthy anxieties. Anxiety is healthy when it serves as an alarm system to let us know something is not right and promotes safety. For example. if your heart rate accelerates and your breathing quickens when you realise you have prescribed penicillin in a penicillin-allergic patient, this alerts you to a problem, and you address this. Thank you, anxiety.

The time anxiety is considered unhealthy is under two conditions: (1) when we have anxiety but there is no threat and you are stressed at home on a Sunday morning when you are not at work, and (2) if your anxiety response is out of proportion, like having a panic attack if you are asked to cover eye casualty instead of attending your normal session. If either of these things happen and anxiety is not serving a useful purpose, please seek support.

Here are some brilliant links to videos to help calm you down:

- For calming and relaxing exercises, visit:

www.mind.org.uk/need-urgent-help/

what-can-i-do-to-help-myself-cope/

relaxing-and-calming-exercises/ - If you need a quick breather, this is a serene 60-second meditation tool that can help calm you down:

www.pixelthoughts.co/ - If you fancy something more creative and meditative, try

weavesilk.com - And if you ever need urgent help and you feel you can’t talk to your friends or family, you can turn to Mind. The chances are though, other people at work will be able to relate to how you feel:

www.mind.org.uk/need-urgent-help/

5. Employ a coping mechanism

In general, better emotional intelligence (understanding the cause of our emotions) could allow us to differentiate between subjective and objective problems, and reflecting on why you feel the way you do with others over a coffee can be a good way to achieve this (everyone loves a coffee break).

This could also be achieved through support groups, potentially as an optional extra after weekly ophthalmology teaching amongst trainees, cultivating a sense of shared understanding. Reflect on regulating emotions, recognise errors and have a space to express self-doubt, which can also mitigate the impact of poor communication between colleagues at work. Moreover, mentoring others who are at higher risk of vulnerabilities, such as junior colleagues, may mitigate their risk of burnout but could be argued to require organisational change. You can always ask a junior colleague how they are doing. Sometimes, change starts with us.

Meditation, breathing exercises, yoga or cognitive skills are all great ways to manage and minimise burnout. If you can use cognitive reframing strategies to reduce intrusive thoughts, you can address negative self-talk head on.

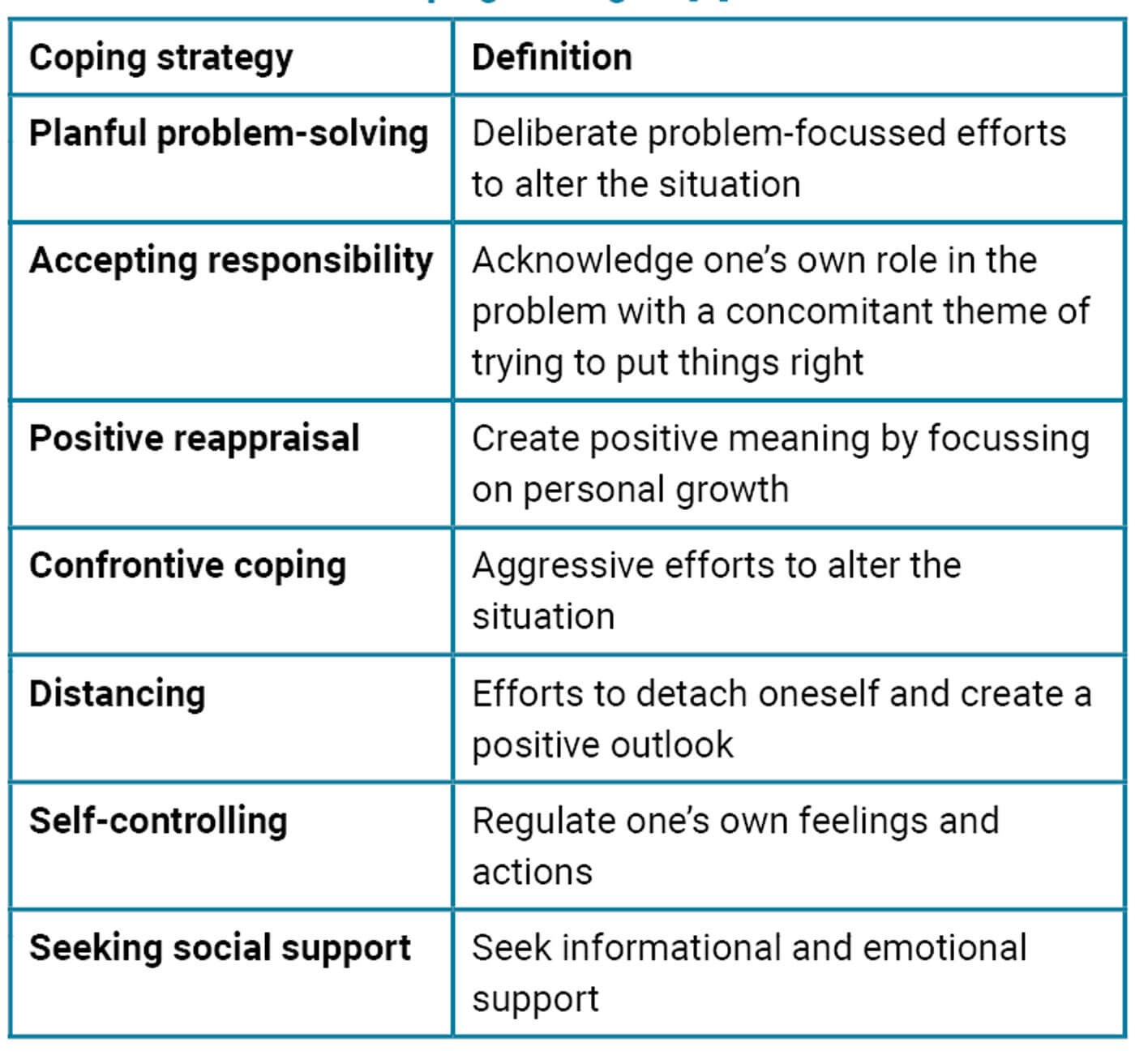

Try to employ planful problem-solving alongside positive reappraisal, accepting responsibility and self-control while seeking social support as coping mechanisms (Table 1).

Table 1: Definitions of coping strategies [7].

Finally, you don’t have to stay

You are the master of your own destiny. Though you may have been led to believe that you are only capable of being a clinician, the truth is you have many highly transferable skills, and if this job no longer provides what you need from it, it is entirely reasonable to make moves towards alternative careers. Look after yourselves, and each other.

References

1. Lemaire JB, Wallace JE. Burnout among doctors. BMJ 2017;358:j3360.

2. Henderson M, Brooks SK, Del Busso L, et al. Shame! Self-stigmatisation as an obstacle to sick doctors returning to work: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2012;2(5):e001776.

3. McKinley N, McCain RS, Convie L, et al. Resilience, burnout and coping mechanisms in UK doctors: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020;10(1):e031765.

4. Balendran B, Bath MF, Awopetu AI, Kreckler SM. Burnout within UK surgical specialties: a systematic review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2021;103(7):464-70.

5. Ansari AS, Tung ASW, Wright DM, et al. Stress and cataract surgery: A nationwide study evaluating surgeon burnout. Eur J Ophthalmol 2023;33(4):1640-9.

6. Health Education England. Definition: resilience.

https://hee.nhs.uk/hee-your-area/

wessex/education-training/doctors/

keep-calm-workshop/resilience.

[last accessed May 2023]

7. Oliver D. David Oliver: When “resilience” becomes a dirty word. BMJ 2017;358:j3604.

8. Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, et al. Dynamics of a Stressful Encounter: Cognitive Appraisal, Coping, and Encounter Outcomes. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986;50(5):992-1003.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME