Uveitis, characterised by inflammation of the uvea – the eye’s middle layer comprising the iris, ciliary body, and choroid – remains a leading cause of visual impairment worldwide [1]. It primarily affects adults aged 20–50 years.

Untreated uveitis may cause cataracts, glaucoma, macular edema, retinal detachment, optic nerve damage and vision loss. This complex group of inflammatory eye diseases affects 38–714 per 100,000 people globally and accounts for 3–10% of vision impairment in developed countries [2].

A review recently published in JAMA by Dr Maghsoudlou and colleagues provides an updated synthesis of current evidence regarding the epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of adult uveitis [1]. This publication offers valuable insights into five key themes that define modern uveitis management.

Theme 1: Geographic variations drive different disease patterns

The review demonstrates significant geographic variations in uveitis presentation and aetiology. These differences have important implications for clinical practice, particularly in our increasingly globalised world.

In high-income countries such as the UK, infectious causes account for only 11–21% of uveitis cases, with toxoplasmosis (5–7%) and herpes-related uveitis (5–15%) being the most common infectious culprits. Conversely, in low- and middle-income countries, infections comprise up to 50% of cases, with tuberculosis-related (8–13%) and HIV-related (10–14%) uveitis being far more prevalent [3-6].

Regional disease patterns also emerge consistently. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease shows higher prevalence in East Asian populations, whilst Behçet disease demonstrates geographic clustering along historical Silk Road regions, where it can account for up to 30% of all uveitis cases [7,8].

For clinicians, this emphasises the importance of detailed travel and ethnic history when evaluating patients with uveitis, particularly in diverse populations such as those found in major British cities.

Theme 2: Age and gender patterns reveal important clinical clues

The demographic characteristics of uveitis provide valuable diagnostic insights. The review confirms that uveitis predominantly affects young and middle-aged adults, with 60–80% of cases occurring in individuals aged 20–50 years. This age distribution is crucial for differential diagnosis [9,10].

Gender patterns prove particularly informative, varying significantly by subtype. Whilst uveitis shows a slight female predominance overall (57% of cases), specific conditions demonstrate marked differences. HLA-B27-associated uveitis shows a clear male predominance with a male-to-female ratio of 1.5:1 [9,10].

Conversely, uveitis associated with multiple sclerosis shows a strong female bias (75% female), as does juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis (50–80% female) and sarcoidosis-related uveitis (55–64% female). These patterns provide important diagnostic clues when combined with other clinical features [9,10].

Theme 3: Anatomical classification determines treatment strategy

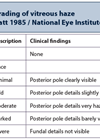

The anatomical approach to uveitis classification has proven fundamental to modern management strategies, with each location requiring distinct therapeutic approaches. The review reinforces the importance of accurate anatomical localisation using slit lamp examination [1,11].

Anterior uveitis, affecting the iris and ciliary body, represents the most common form in Western countries (41–60% of cases). It typically presents with eye pain, redness and photophobia, and is frequently unilateral (53% of cases). Anterior uveitis generally responds well to topical corticosteroids.

Intermediate uveitis, affecting the pars plana and peripheral retina (9–15% of cases), often presents more subtly with painless floaters and blurred vision. This form is typically bilateral and may be associated with systemic conditions such as multiple sclerosis.

Posterior uveitis, involving the choroid and / or retina (17–23% of cases), represents the most challenging form to treat and carries the highest risk of sight-threatening complications. Panuveitis, affecting all uveal layers (7–32% of cases), typically requires the most aggressive systemic treatment.

The anatomical distinction is crucial because treatment intensity and monitoring requirements increase dramatically as one moves from anterior to posterior disease, reflecting both increased complication risk and reduced efficacy of topical treatments.

Theme 4: Treatment revolution through evidence-based medicine

The review documents the significant evolution in uveitis treatment over the past two decades. The shift from empirical corticosteroid-dependent approaches to evidence-based, targeted immunosuppression represents a genuine paradigm change.

For anterior uveitis, topical corticosteroids such as prednisolone acetate provide first-line therapy. The evidence supports hourly initial dosing during waking hours for seven days, followed by gradual tapering based on clinical response.

The changes have been most significant in posterior uveitis management. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) have emerged as first-line systemic therapy. The SITE cohort study demonstrated that methotrexate achieved control of inflammation in 52.1% of patients with posterior or panuveitis, whilst mycophenolate mofetil controlled inflammation in 70.9% of similar patients at 12 months [12,13].

The introduction of biologic therapy has transformed outcomes for patients with refractory disease. Adalimumab, the first biologic approved specifically for uveitis, showed strong efficacy in the VISUAL trials. In patients with active disease, adalimumab extended time to treatment failure from 13 weeks with placebo to 24 weeks, whilst reducing treatment failure rates from 78.5% to 54.5% [14,15].

Adalimumab represents a genuine paradigm shift in uveitis care. What’s remarkable about the VISUAL trials is not just the numbers – extending time to treatment failure from 13 to 24 weeks – but what this means for patients’ lives. We’re talking about people who can return to work, spend time with their families, and regain independence they thought they’d lost forever. The success of adalimumab has validated the TNF-alpha pathway as a therapeutic target and paved the way for other biologics and janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors. We’re entering an exciting era where we can offer patients genuine hope for sustained remission.

Theme 5: Early recognition and prompt treatment prevent vision loss

The final key theme emphasises the critical importance of early recognition and prompt treatment in preventing irreversible vision loss. The review provides data on complications whilst demonstrating the potential for good outcomes with timely intervention.

Severe and chronic inflammation can lead to sight-threatening complications including cataracts (18–49% of cases), glaucoma (7–56%), and macular oedema (8–10%). These complications can develop despite treatment, but their frequency and severity are reduced with early, appropriate intervention [16,17].

Patients with suspected uveitis should be referred to an ophthalmologist for definitive diagnosis and treatment. Urgent same-day referral is essential for patients with vision loss, visual distortion or severe pain, particularly when accompanied by systemic features.

For infectious uveitis, the evidence supports aggressive antimicrobial treatment combined with judicious anti-inflammatory therapy. Tuberculosis-related uveitis, treated with standard World Health Organization (WHO)-recommended regimens, achieves complete resolution in 83% of patients [18]. Viral uveitis responds well to combination antiviral and anti-inflammatory treatment [19,20].

The prognosis has improved significantly with modern approaches. The VISUAL III study demonstrated that adalimumab could increase disease quiescence rates from 34–85% over three years, offering hope for sustained remission in previously refractory disease [21].

Conclusion

This comprehensive review highlights five key themes that define modern uveitis management: the importance of geographic and demographic factors in diagnosis, the central role of anatomical classification, the evolution in evidence-based therapeutics, and the critical importance of early recognition and treatment.

For practising ophthalmologists and general practitioners, these insights provide a framework for improving patient outcomes. The geographic variations remind us to consider travel and ethnic history. The demographic patterns offer diagnostic clues. The anatomical approach provides a logical treatment framework, whilst therapeutic advances offer genuine hope for patients with previously intractable disease.

The evolution from corticosteroid-dependent treatment to targeted immunosuppression and biologic therapy represents one of the great success stories in modern ophthalmology. As new therapeutic targets such as JAK inhibitors show promise, the future for patients with uveitis looks increasingly positive.

References

1. Maghsoudlou P, Epps SJ, Guly CM, et al. Uveitis in Adults: A Review. JAMA 2025;334(5):419–34.

2. Miserocchi E, Fogliato G, Modorati G, et al. Review on the worldwide epidemiology of uveitis. Euro J Ophthalmol 2013;23(5):705–17.

3. Tsirouki T, Dastiridou A, Symeonidis C, et al. A Focus on the Epidemiology of Uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2018;26(1):2–16.

4. Bajwa A, Osmanzada D, Osmanzada S, et al. Epidemiology of uveitis in the mid-Atlantic United States. Clin Ophthalmol 2015;9:889–901.

5. Barisani-Asenbauer T, MacA SM, Mejdoubi L, et al. Uveitis- a rare disease often associated with systemic diseases and infections - a systematic review of 2619 patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2012;7:57.

6. Dick A, Okada A, Forrester J. Practical Manual of Intraocular Inflammation, 1st Edition. Boca Raton, CRC Press; 2008.

7. Chang JH, Wakefield D. Uveitis: a global perspective. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2002;10(4):263–79.

8. Jabs DA, Busingye J. Approach to the diagnosis of the uveitides. Am J Ophthalmol 2013;156(2):228–36.

9. Thorne JE, Suhler E, Skup M, et al. Prevalence of Noninfectious Uveitis in the United States: A Claims-Based Analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016;134(11):1237–45.

10. Yeung IY, Popp NA, Chan CC. The role of sex in uveitis and ocular inflammation. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2015;55(3):111–31.

11. Jabs DA, McCluskey P, Palestine AG, et al. The standardisation of uveitis nomenclature (SUN) project. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2022;50(9):991–1000.

12. Gangaputra S, Newcomb CW, Liesegang TL, et al. Methotrexate for ocular inflammatory diseases. Ophthalmology 2009;116(11):2188–98.e1.

13. Daniel E, Thorne JE, Newcomb CW, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil for ocular inflammation. Am J Ophthalmol 2010;149(3):423–32.e1–2.

14. Jaffe GJ, Dick AD, Brézin AP, et al. Adalimumab in Patients with Active Noninfectious Uveitis. N Engl J Med 2016;375(10):932–43.

15. Nguyen QD, Merrill PT, Jaffe GJ, et al. Adalimumab for prevention of uveitic flare in patients with inactive non-infectious uveitis controlled by corticosteroids (VISUAL II): a multicentre, double-masked, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016;388(10050):1183–92.

16. Tomkins-Netzer O, Lightman SL, Burke AE, et al. Seven-Year Outcomes of Uveitic Macular Edema: The Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment Trial and Follow-up Study Results. Ophthalmology 2021;128(5):719–28.

17. Suhler EB, Jaffe GJ, Fortin E, et al. Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of Adalimumab in Patients with Noninfectious Intermediate Uveitis, Posterior Uveitis, or Panuveitis. Ophthalmology 2021;128(6):899–909.

18. Betzler BK, Putera I, Testi I, et al. Anti-tubercular therapy in the treatment of tubercular uveitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surv Ophthalmol 2023;68(2):241–56.

19. Thng ZX, Putera I, Testi I, et al. The Infectious Uveitis Treatment Algorithm Network (TITAN) Report 1-global current practice patterns for the management of Herpes Simplex Virus and Varicella Zoster Virus anterior uveitis. Eye (Lond) 2024;38(1):61–7.

20. Thng ZX, Putera I, Testi I, et al. The Infectious Uveitis Treatment Algorithm Network (TITAN) Report 2-global current practice patterns for the management of Cytomegalovirus anterior uveitis. Eye (Lond) 2024;38(1):68–75.

21. Suhler EB, Adán A, Brézin AP, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Adalimumab in Patients with Noninfectious Uveitis in an Ongoing Open-Label Study: VISUAL III. Ophthalmology 2018;125(7):1075–87.

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.