Benign essential blepharospasm (BEB) is a rare neurological condition which causes involuntary sustained or intermittent muscular contraction of both eyelids and upper facial muscles which cause closure of eyelids, abnormal facial expressions and distress [1].

The term dystonia is an umbrella term which refers to a group of conditions considered movement disorders [2]. People with BEB, like those with dystonia, experience repetitive movements, contractions and contortions [3]. The condition BEB is a focal dystonia of the eyes but can progress to the lower face affecting two or more close areas [4]. Lower facial muscle involvement, including the mouth, tongue and jaw is characteristic of Meige syndrome, which changes the classification from focal to segmental dystonia [5].

The true incidence of BEB is uncertain as many people remain undiagnosed. In one study, only 10% of people were accurately diagnosed with BEB during their first encounter with a medical professional. In another study, 60% of BEB patients saw at least five physicians before they received a definitive diagnosis in a period of between one and five years [6].

Figure 1: Benign essential blepharospasm with phenotype Miege syndrome.

Worldwide, BEB prevalence is estimated 16 to 133 cases per million [7]. In the UK, it affects the lives of around 7000 adults annually [8]. The condition is more prevalent in women, with a ratio of 2.3:1 in men [9,7]. Women also show significantly worse disease [10]. People with BEB can experience severe spontaneous closure of the eyes and functional blindness which can be disabling [11]. Furthermore, repetitive facial and eye movements have been linked to cause social anxiety [12].

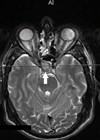

The aetiology of BEB is unknown, however the basal ganglia of the brain in the area that controls blink co-ordination to the neurons of facial muscles is affected [13]. Evidence from neurophysiology and neuroimaging (see Figure 2) shows the involvement of several brain regions (see letters A, B and C) [15].

People with BEB also experience ocular complaints such as dry eyes and sensitivity to light. Mental health issues, specifically depression, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders are also common in BEB and are referred to as non-motor symptoms [1,16]. One study concluded that non-motor symptoms are a part of the condition’s clinical spectrum, and non-motor symptoms have been shown to significantly affect quality of life (QoL) [17-19]. It has detrimental negative impact on activities of daily living and perceived stigma [20].

Figure 2: Abnormal neural activity at rest in BEB [14].

Botulinum toxin (BTX) is considered the treatment of choice for BEB due to its safety and effectiveness [21]. The drug is injected subcutaneously or intramuscularly into affected muscles. Although BTX offers temporary relief, it is not understood why the duration of its treatment efficacy varies [22]. Whilst it can last between three to six months, in many cases effectiveness can be for a period of six to eight weeks [23]. However, there is no contraindication to a shorter treatment cycle. In fact, Jankovic, et al. suggest that six-week treatment cycles are clinically safe [24]. Therefore, it may be concluded that a three-monthly scheduled treatment plan is an economical rather than QoL decision.

Importantly, early introduction of BTX is recommended – it is safe as a long-term therapy and will benefit the patient and family / social interaction, which leads to less depression [12]. Leplow, et al. found practitioners’ partnership during the administration of BTX played a vital role in education, reducing treatment intervals, reducing psychological stress, and preventing worsening conditions [25]. Prompt access to treatment is therefore important.

In part, the UK Rare Disease Framework 2023 prioritises helping patients get a final diagnosis faster, increasing awareness among healthcare professionals, better co-ordination of care, and improving access to specialist care, treatment and drugs. Specifically, the areas explored in this study relevant to people with BEB were improving access to treatment and raising awareness amongst service providers and others of the effects of the condition on family, social relationships, and work [26]. The largest patient-public involvement exercise for BEB also identified the need for more rapid diagnosis as a priority for patients [27].

Despite numerous QoL studies, there are no qualitative studies on the lived experience of BEB in regard to treatment and care. Giving BEB patients a more influential voice provided insightful information on the challenges of their daily life, specifically on seeking treatment and care. It helped to readdress local treatment and optimise quality of care [17]. This research sought to address the gap between policy, theory and practice, and identify knowledge gaps in the literature.

Participants

A purposive sample of 10 patients representing the cross section of patients frequenting the Eye Dystonic Clinic were identified and invited to take part in the study. Interviews were digitally recorded verbatim. Non-English-speaking patients were excluded due to translation cost. All participants gave consent to be interviewed individually and collectively as a group and for the data to be used for research purposes. The sample included seven females and three males with BEB; the age range was 51–88 years.

Figure 3: Superordinate and subordinate themes of BEB.

Data analysis

An inductive thematic analysis was adopted to examine, organise and analyse the narrative data. NVivo software (NVivo qualitative data analysis software; QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 10, 2014) was employed. The analysis undertaken broadly took place over five stages: familiarisation (reading transcripts and listening to recordings in detail to gain an overview of content), thematic analysis (developing a coding scheme), indexing (applying the codes systematically to the data), charting (re‐arranging the data according to the thematic content to allow comparative), and mapping and interpretation (defining key concepts, delineating the range and nature of phenomena, creating typologies, findings associations, providing explanations and developing strategies).

Guided by this approach, a transcript was developed, and 21 initial codes were included in the framework. The coding framework was reviewed, discussed and revised until reflective of participant views and a final agreed version. The codes were subsequently grouped into five overarching themes. The coding of each theme and subtheme until final interpretation of findings was reached.

Results

The data was examined in relation to the WHO (2020) element of quality of health service (effective, safe, people centred, timely, equitable, integrated and efficient), employing the use of a practitioner and researcher’s lens [28]. Interpretive phenomenological analysis was the chosen methodological approach to facilitate ‘action’ to deliver high-quality outpatient care that takes account of the physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual wellbeing of patients. Ethics was granted for patient participants’ involvement. The findings highlighted issues that are common to many people with rare conditions and some that were specific to individuals with BEB disorder.

The first theme illustrates a critical area of impact for individuals with BEB – a lack of knowledge which also affected primary care professionals, the incredible debilitating physical and psychological health. The second theme, loss of social richness, reflects the participants’ inability to interact due to poor vision and feelings of depression, anxiety and perceived stigma. The third theme focused on fleeting normality and how temporary periods of normal blink with botulinum toxin treatment inspired hope. The final theme highlighted was the battle for adequate care, representative of the unpleasant interaction experienced when patients desperately demand an earlier appointment when their eyelid spasm returns sooner than their previously planned appointment.

Discussion

This study explored the experiences of living with BEB from the individual’s perspective and the collective views of service users. Some experiences were previously identified in the literature example: clinicians’ lack of knowledge which impaired their diagnostic abilities [6]; the physical and psychological burden of depression and anxiety [1]; the varying effects of botulinum toxin BTX [22,23]; the effects of BEB on daily activities and the effects of perceived stigma and its impacts on QoL [20] demonstrated a real need to respond to the needs of participants to reduce periods of delayed treatment. However, the lives of people with BEB can be improved with prompt diagnosis and referral to treatment. And a patient-centred approach while scheduling appointments as shorter treatment cycles have been shown to be clinically safe [24].

Conclusion

This study directly sought to raise awareness of BEB and improve the clinical environment for people with BEB. The study demonstrated diagnostic and referral delays led to untimely treatment which resulted in a period of ‘incredible debilitation’ – they affected vision, caused functional limitation and decreased psychological health. Specialist dystonia eye clinics provided hope but are often overbooked which results in untimely treatment. Clinic reorganisation was effective, and the introduction of person-centred care helped in the amelioration of BEB physical and psychological symptoms.

The introduction of the dystonia telemedicine clinic provided safety netting and promptly assessed clinical symptomology to offer reassurance to BEB patients. It provided an integrated approach to expediting patients to the main eye dystonia clinic for timely treatment. In addition, further training for junior doctors, optometrist and specialist nurses provided an equitable approach to treatment and care. Finally, the introduction of more central and satellite eye dystonia clinics provided an efficient means of establishing timely treatment in secondary care. However, the co-ordination of referral from primary to secondary care still presents a significant barrier to BEB treatment, QoL and the reduction of perceived stigma.

References

1. Valls-Sole J, Defazio G. Blepharospasm: Update on epidemiology, clinical aspects, and pathophysiology. Front Neurol 2016;7:45.

2. Lewis L, Butler A, Jahanshahi M. Depression in focal, segmental, and generalized dystonia. J Neurol 2008;255(11):1750–5.

3. Gürsoy AE, Ugurad I, Babacan-Yıldız G, et al. Effects of botulinum toxin type a on quality of life assessed with the WHOQOL-BREF in hemifacial spasm and blepharospasm. Neuro, psych brain res 2013;19(1):12–8.

4. Tolosa E, Martí M J. Blepharospasm-oromandibular dystonia syndrome (Meige’s syndrome): Clinical aspects. Adv Neurol 1988;49:73–84.

5. Hwang CJ, Eftekhari K. Benign Essential Blepharospasm: What We Know and What We Donʼt. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2018;58(1):11–24.

6. Wakakura M, Yamagami A, Iwasa M. Blepharospasm in Japan: A Clinical Observational Study From a Large Referral Hospital in Tokyo. Neuroophthalmology 2018;42(5):275–83.

7. Defazio G, Livrea P. Epidemiology of primary blepharospasm. Mov Disord 2002;17(1):7–12.

8. https://www.dystonia.org.uk/blepharospasm

9. Coscarelli JM. Essential blepharospasm. Semin Ophthalmol 2010;25(3):104–8.

10. Müller J, Kemmler G, Wissel J, et al. The impact of blepharospasm and cervical dystonia on health-related quality of life and depression. J Neurol 2002;249(7):842–6.

11. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/

Benign-Essential-Blepharospasm-Information-Page

12. Streitová H, Bareš M. Long-term therapy of benign essential blepharospasm and facial hemispasm with BTX A: retrospective assessment of the clinical and Quality of Life impact in patients treated for more than 15 years. Acta Neurol Belg 2014;114(4):285–91.

13. Berardelli A, Rothwell JC, Day BL, Marsden CD. Pathophysiology of blepharospasm and oromandibular dystonia. Brain 1985:108(Pt3):593–608.

14. Baker RS, Andersen AH, Morecraft RJ, Smith CD. A functional magnetic resonance imaging study in patients with benign essential blepharospasm. J Neuroophthalmol 2013;23(1):11–5.

15. Jiang W, Lan Y, Cen C, et al. Abnormal spontaneous neural activity of brain regions in patients with primary blepharospasm at rest. J Neurol Sci 2019;403:44–9.

16. Conte A, Berardelli I, Ferrazzano G, et al. Non-motor symptoms in patients with adult-onset focal dystonia: Sensory and psychiatric disturbances. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016;22 (Suppl 1):S111–4.

17. Ferrazzano G, Berardelli I, Conte A, et al. Motor and non-motor symptoms in blepharospasm: clinical and pathophysiological implications. J Neurol 2019;266(11):2780–5.

18. Hall TA, Mcgwin G, Searcey K, et al. Health-related Quality of Life and psychosocial characteristics of patients with benign essential blepharospasm. Arch Ophthalmol 2006;124(1):116–9.

19. Pekmezovic T, Svetel M, Ivanovic N, et al. Quality of Life in Patients with focal dystonia. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2009;111(2):161–4.

20. Lawes-Wickwar S, McBain H, Hirani SP, et al. Which factors impact on quality of life for adults with blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm?. Orbit 2021;40(2):110–9.

21. Costa PG, Aoki L, Saraiva FP, Matayoshi S. BTX in the treatment of facial dystonia: evaluation of its efficacy and patientsʼ satisfaction along with the treatment. Arq Bras Oftalmol 2005;68(4):471–4.

22. Jinnah HA, Berardelli A, Comella C, et al. The focal dystonias: Current views and challenges for future research. Mov Disord 2013;28(7):926–43.

23. Calace P, Cortese G, Piscopo R, et al. Treatment of blepharospasm with botulinum neurotoxin type A: Long-term results. Eur J Ophthalmol 2003;13(4):331–6.

24. Jankovic J, Comella C, Hanschmann A, Grafe S. Efficacy and safety of incobotulinumtoxinA (NT 201, Xeomin) in the treatment of blepharospasm: A randomized trial. Mov Disord 2011;26(8):1521–8.

25.Leplow B, Eggebrecht A, Pohl J. Treatment satisfaction with BTX: a comparison between blepharospasm and cervical dystonia. Patient Prefer Adherence 2017;11:1555–63.

26. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/

england-rare-diseases-action-plan-2023/england

-rare-diseases-action-plan-2023-main-report

27. Murta FR, Waxman J, Skilton A, et al. The first UK national blepharospasm patient and public involvement day; identifying priorities. Orbit 2020;39(4):233–40.

28. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/

detail/quality-health-services

[All links last accessed April 2025]

Declaration of competing interests: This study was funded by the Burdett Nursing Trust.