How the integration of service improvement technology, and health promotion will allow eye care professionals to overcome current and future challenges.

The future of eye care in the UK is at a precipice. Hospital attendances are increasing year on year, yet healthcare spending is at its most consistently lean since the inception of the NHS. Currently, ophthalmology clinics account for nearly 10% of all outpatient appointments, with demand expected to increase by 40% over the next 20 years [1].

However, capacity issues are current, with 67% of eye health departments using locums to fill empty consultant posts and 85% of units dependent on waiting list initiative and out of hours sessions to cope with service demands. Tragically, 22 people are estimated to lose their sight each month due to healthcare system delays. As the age and complexity of care of our patients continues to increase, eye services are set to face unprecedented pressures in an increasingly financially restricted environment: already, Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) in England have begun rationing cataract surgery [2], despite National Institute of Health & Care Excellence (NICE) accreditation as one of the most cost-effective interventions available. These issues are likely to be magnified by the extensive repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as longstanding concerns regarding low workforce recruitment and retention and the continued erosion of ophthalmic education in medical schools.

Although the above statistics make for dismal reading, we must remain hopeful, not least because our patients deserve better but also because there remain several reasons to be optimistic: ophthalmology remains a dynamic, innovative specialty which offers countless opportunities for self-development and job satisfaction. Moreover, following a coordinated campaigning effort by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists and national charities, vision health is consistently identified as a public health priority, reflected in the Government’s endorsement of the UK Vision Strategy and VISION 2020 UK at the highest level and its publishing of the first ever Public Health Indicator for eye health to measure the rate of preventable sight loss [3], and supported by the formation of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Eye Health and Visual Impairment [4].

“empowering multidisciplinary relationships and breaking down the barriers to collaboration will be key to consolidating existing improvements and tackling the challenges facing eye care”

It is no coincidence, therefore, that eye care professionals (ECPs) constitute one of the most professionally diverse employee bodies in healthcare, drawing on the expertise of ophthalmologists, optometrists, orthoptists, ophthalmic nurses, ophthalmic photographers, opticians, ocularists, general practitioners and pharmacists to improve vision in society. Indeed, multi-professional working is crucial in the delivery of successful clinical outcomes and underpins the pioneering culture of the field. It is becoming increasingly clear that the strengthening and streamlining of these collaborative ties will be crucial to tackling the challenges facing the national delivery of eye care. In particular, I propose three areas where multi-professional working is likely to have the greatest impact:

- The implementation of integrated pathways at scale

- The incorporation of technological advances to improve service delivery

- Local initiatives to promote eye health awareness and screening

Service integration

Although the imperative for training more staff is clear, the type of services that will be provided needs to be considered when planning the future workforce.

The building of strategic relationships between ophthalmologists and allied health professionals has allowed ECPs to successfully navigate primary and specialist services. However, the communication between community and hospital services is far from uniform across different regions, often involving many providers in a network of care, thus risking inefficiency, duplication of work and negative impacts on patient safety. Ultimately, multi-professional collaboration is essential to improve patient flow and establish an integrated service which would encompass, for example, glaucoma repeat measures, cataract post-op assessments and minor eye conditions, in order to free up hospital eye service capacity.

While there exist opportunities to expand the roles of the non-medical workforce to deliver more services, optometrists and orthoptists need to be empowered to take on the long-term eye care of patients through the proper integration of communication systems and the establishment of consistent national training and sustainable payment schemes, which are currently lacking [5]. In the first instance, there needs to be a national training and accreditation programme for non-medical ECPs to ensure an appropriately trained and informed workforce across the continuum of eye care. Furthermore, collaboration between specialty colleges, clinical directors, trusts and CCGs will be crucial to develop and implement these national pathways while safeguarding the opportunities for trainee ophthalmologists to develop their clinical acumen.

Finally, there is a lack of data surrounding the quality and performance of eye health services [6]. Further collaboration between community and hospital services in the development of integrated data collection and communication software, facilitated by NHS England, would allow experts to fully appreciate the capacity problems facing eye care, and use this insight to develop long-term solutions to prevent dangerous delays.

Technology

The scale and breadth of the challenges faced by health services demand a multi-faceted approach. The increasing development and implementation of technological advances have already offered many solutions to the capacity, financial and training problems in eye care.

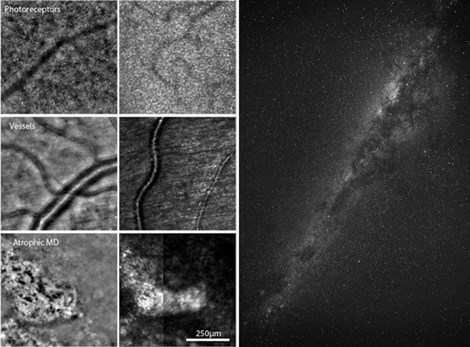

Figure 1: Plato and Aristotle spoke of mimesis as the re-presentation of nature. Left-hand side: Cellular structures visible using fundus camera (left column) vs. bright field scan (right column) adaptive optics ophthalmoscopy [7]; Right-hand side: Stars by Philippe Donn from Pexels. Both images used with permission.

Serviced by the accessibility of the ocular media and the strength of industry partnerships, ophthalmology has been at the forefront of an innovative wave of technological breakthroughs. Since the rapid clinical expansion of optical coherence tomography just over a decade ago, we have witnessed ground-breaking advancements in imaging such that we can now almost routinely visualise previously unseen structures on a cellular level to track disease and profile extraocular disease risk (Figure 1) [7,8], and use artificial intelligence to achieve superhuman retinal diagnostic performance [9]. Equally remarkable advances have been made in the realm of ocular therapeutics, with cellular regeneration and immune modulatory strategies reaching the forefront of clinical trials in dry age-related macular degeneration [10], spurred on by our emerging appreciation of this untreatable disease’s underlying pathophysiology [11].

In future, the digitalisation of ophthalmology in practice has the potential to transform patient triaging through the implementation of responsive chatbots, teleophthalmology and automated appointment platforms, all of which are in the final stages of development. Simultaneously, we are likely to experience the expansion of augmented reality use, both in simulation training and in the operating theatre to improve clinical outcomes [12].

At the foundation of all these exciting new advances is the combined effort of healthcare workers, researchers, engineers and informaticians – each drawing on their unique experiences and skills to produce clinically-applicable technology which is greater than the sum of its parts. As the place of technology in healthcare is still being debated, innovators need to work closely with policy makers, service managers and ethical committees to ensure that existing inventions can move swiftly from bench to clinic. In these negotiations, a multi-professional angle will be key to ensuring that patients receive most benefit without widening the existing inequalities in digital service provision.

Health promotion

The invention of spectacles in the 13th century is considered crucial in spurring economic development in Europe by essentially doubling the working life of skilled craftsmen [13]. There are now numerous reports demonstrating the positive economic impact of sight loss prevention initiatives.

In England, the collaboration of ECPs and public health in the implementation of the NHS Diabetic Eye Screening Programme has successfully improved the care of people with diabetes, with increasing efforts to reduce variability in screening outcomes between local services [14]. In Scotland, the introduction of new NHS-funded eye examinations has allowed patients who would not have otherwise had their eyes examined to benefit from early intervention and monitoring of glaucoma and other ophthalmic pathologies. Early analyses suggest that the policy’s economic benefits, which may be as high as £440 million (in one year), far outweigh the cost of setting-up the service (between £20 million and £30 million) [15].

However, up to 50% of glaucoma remains undiagnosed in the community, and research suggests that poorer households have not yet responded to these policy changes as quickly as more affluent households, perhaps due to the perceived pressure to buy spectacles after examinations. Moving forward, collaboration between optometrists, ophthalmologists, public health and commissioners is essential to help increase patient access to local services [16]. Tackling the associated inequalities of eye disease will require multi-professional working, which will be critical to the development and evaluation of ophthalmic outreach services to areas of relative deprivation.

Finally, multi-professional working is critical in ensuring that the ophthalmic outcomes of children improve in parallel with those of adults. Collaboration between local authorities to ensure widespread adoption of recent Public Health England child vision screening recommendations is essential to actively detect visual defects at an early stage [17]. Where appropriate, the work of paediatric eye clinic liaison officers in facilitating support for children and their families is critical, particularly for adolescents with complex disorders transitioning to adult services. Again, children of lower socioeconomic status are disproportionately impacted by visual impairment. Here, vision health charities also have an important role to play in providing information, influencing opinion and shaping policy, drawing on the diverse professional background of their members and volunteers to prevent visual loss among these hard-to-reach groups.

Conclusions

The collaboration of individuals within clinical, academic and political sectors has shaped the landscape of eye care provision to the benefit of patients. In particular, the wealth of advancements in service integration, technology and local policy within ophthalmology are the result of innovative, multi-professional working within the field. In future, empowering multidisciplinary relationships and breaking down the barriers to collaboration will be key to consolidating existing improvements and tackling the challenges facing eye care.

References

1. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Workforce Census 2018:

https://rcophth.ac.uk/

publications/workforce-census-2018/

2. Iacobucci G. Leading ophthalmologist vows to stamp out “unjustified” screening for cataract surgery. BMJ 2019;365:l2326.

3. Vision UK. England Vision Strategy priorities. 2018:

https://www.visionuk.org.uk/

england-vision-strategy-priorities-2/

4 All-Party Parliamentary Group on Eye Health and Visual Impairment. See the light: Improving capacity in NHS eye care in England. 2018:

https://www.rnib.org.uk/professionals/

health-professionals/appg-eye-capacity

5. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. RCOphth response to NHS England’s consultation on Developing the long-term plan for the NHS. 2018:

https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/

uploads/2019/08/RCOphth-response-to-

NHS-England-10-year-plan-consultation.pdf

6. The College of Optometrists. Capacity issues within ophthalmology are real and current. 2019:

https://www.college-optometrists.org/

the-college/blogs/capacity-issues-

within-ophthalmology-.html

7. Paques M, Meimon S, Rossant F, et al. Adaptive optics ophthalmoscopy: Application to age-related macular degeneration and vascular diseases. Prog Retin Eye Res 2018;66:1-16.

8. Farrah E, Webb DJ, Dhaun N. Retinal fingerprints for precision profiling of cardiovascular risk. Nat Rev Cardiol 2019;16:379-81.

9. De Fauw J, Ledsam JR, Romera-Paredes B, et al. Clinically applicable deep learning for diagnosis and referral in retinal disease. Nat Med 2018;24:1342.

10. Walsh F. Gene therapy first to ‘halt’ most common cause of blindness. BBC (online) 2019:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/

news/health-47226987

11. Morgan BP, Harris CL. Complement, a target for therapy in inflammatory and degenerative diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2015;14:857-77.

12. VRmagic. VRmagic Presents Slit Lamp Simulator. 2018:

https://www.vrmagic.com/simulators/

news-events/news/article/vrmagic-

presents-slit-lamp-simulator/

13. Landes D: The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Are Some So Rich and Others So Poor? WW Norton & Company; 1998.

14. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Diabetic Retinopathy Guidelines. 2012:

https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/

uploads/2014/12/2013-SCI-301-FINAL-DR-

GUIDELINES-DEC-2012-updated-July-2013.pdf.

15. Scottish Government. Community eyecare services: review. 2017:

https://www.gov.scot/publications/

community-eyecare-services-review/pages/3/

16. Day F, Buchan JC, Cassells-Brown A, et al. A glaucoma equity profile: correlating disease distribution with service provision and uptake in a population in Northern England, UK. Eye 2010;24:1478-85.

17.Public Health England. Child vision screening. 2017:

https://www.gov.uk/government/

publications/child-vision-screening

(All links last accessed June 2020)

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME