The compact volume depicted in Figure 1 bears the simple title Pharmacopoeia. The book originally belonged to the author’s father, the late John King. A pharmacist by profession, John King maintained a keen interest in matters pertaining to pharmaceutical history.

Figure 1: Front cover of the pharmacopoeia.

Bound in red leather, the front cover further informs readers that it was published by the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh and the book cost the not inconsiderable amount at the time of two shillings and six pence. The Infirmary’s seal is prominently embossed on the cover.

Upon opening the book, the first page expands this information. Published in 1908, we learn that this is the third edition of the pharmacopoeia, and that it has been revised and enlarged by one Thomas Alexander, who is described as ‘Chemist to the Royal Infirmary’. The book was sold by the well-known Edinburgh firm of James Thin. Based in the South Bridge thoroughfare, this establishment was the principle academic bookseller of the time in the city of Edinburgh.

Intended as a reference formulary and an official guide to the uses and effects of medicinal drugs (including directions and dosages), the pharmacopoeia’s contents are divided into six separate sections, each dealing with a particular area of medicine. It is the third section that is entitled ‘Eye Department’. Interestingly, the term ophthalmology does not appear.

Despite covering only 12 pages, the eye section gives the modern reader a fascinating insight into the ocular conditions – and their methods of treatment – prevalent in the days before the first world war. The first page solemnly informs readers by means of a memorandum that “In the preparation of materials intended for application to the eye aseptic methods of manipulation must be followed”. Sterile distilled water is found to be the most frequently used excipient.

The formulary shows that the early twentieth century ophthalmologists had at their disposal a somewhat limited range of ocular medications such as:

1. caustics

2. collyrias (eye lotions)

3. instillations and mixtures (eye drops)

4. pills and powders

5. unguenta (ointments)

Eye diseases considered suitable for the medications described included: conjunctivitis and septic keratitis, corneal ulcers, intraocular affections, strumous affections of the eye, blepharitis and styes. The disease entity of glaucoma is not referred to.

Examination of a sample of the pharmacopoeia’s 32 medical entries proves illuminating.

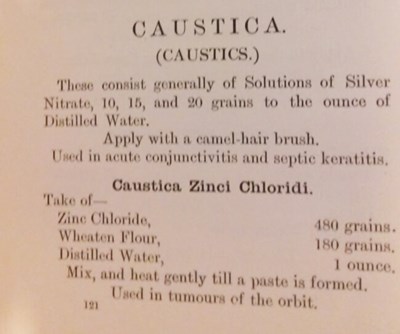

Figure 2: Caustic solutions containing silver nitrate and zinc chloride.

The use of caustic solutions to burn or corrode organic tissue is thankfully no longer undertaken in treating eye disease. However, Figure 2 shows silver nitrate and zinc chloride being used in this way to treat conjunctivitis and ‘tumours of the orbit’. Their application with a camel hairbrush may not have been particularly comfortable.

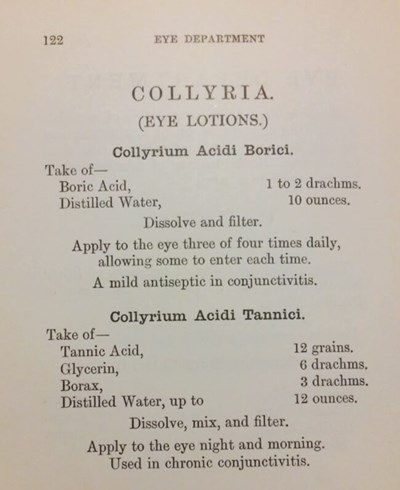

Figure 3: Conjunctivitis treatments containing boric acid and tannic acid.

Conjunctivitis is the disease most commonly treated within the ocular pages of the pharmacopoeia. Figure 3 shows eye lotion formulations containing boric acid and tannic acid also being used for the treatment of conjunctivitis.

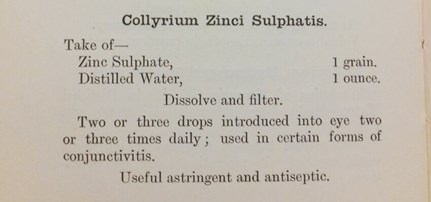

Figure 4: Formulation of zinc sulphate.

Up until recently zinc sulphate was commonly available as an over-the-counter ocular astringent and decongestant. Figure 4 shows its formulation being described as an antiseptic ‘used in certain forms of conjunctivitis’.

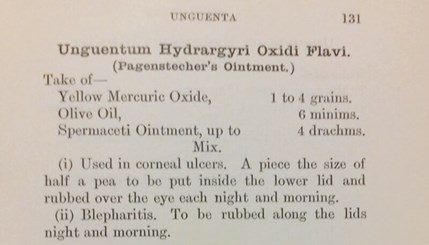

Figure 5: Formulation of Pagenstecher’s Ointment.

A corneal ulcer has always been regarded as an ophthalmic emergency. In 1908 we find it being treated by the intriguing ‘Pagenstecher’s Ointment’. The formulation of this ointment is shown in Figure 5. It is noted that the same ointment was being used to treat blepharitis.

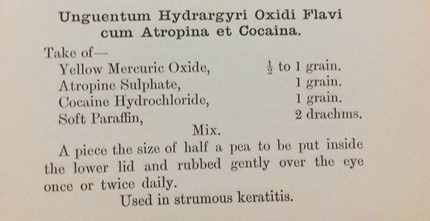

Figure 6: Formulation of ointment containing atropine sulphate and cocaine hydrochloride.

Another condition requiring urgent treatment is keratitis. It is described in the pharmacopoeia as being ‘strumous’. Its treatment was by a potent ointment containing atropine sulphate and cocaine hydrochloride. The details of its formulation are shown in Figure 6.

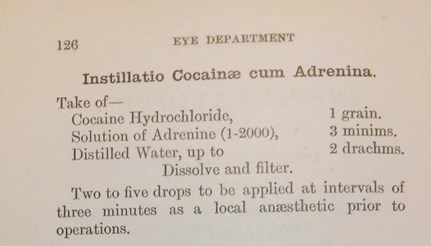

Figure 7: Formulation of local anaesthetic.

Patients requiring a local anaesthetic prior to ocular surgery could be given a mixture of cocaine and adrenaline, the formulation for which is shown in Figure 7.

The early twentieth century was a time of expanding eyecare services under the auspices of the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. In 1903 a separate eye department had been established following a generous donation from the Earl of Moray [1]. It seems likely that the pharmacopoeia described in this article would have been frequently used in this department. Within a few years the list of medications available for the treatment of eye diseases would considerably expand. However, this pocket-sized pharmacopoeia gives us an indication of the early treatment of patients with eye diseases.

Reference

1. Cullen JF. The Princess Alexandra Eye Pavillion (PAEP). Eye News 2019;25(6):6.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME