As indicated in an earlier article in Eye News [1] Dr Cullen was invited in 2000 to the Singapore National Eye Centre (SNEC) as visiting Professor with a specific remit to set up a specialist neuro-ophthalmology service, which was the one ophthalmic subspecialty not then available in this tertiary referral centre already in operation since 1990. From many previous visits to the region he was already aware that the pattern of eye disease there was very different from that seen in the western world [2].

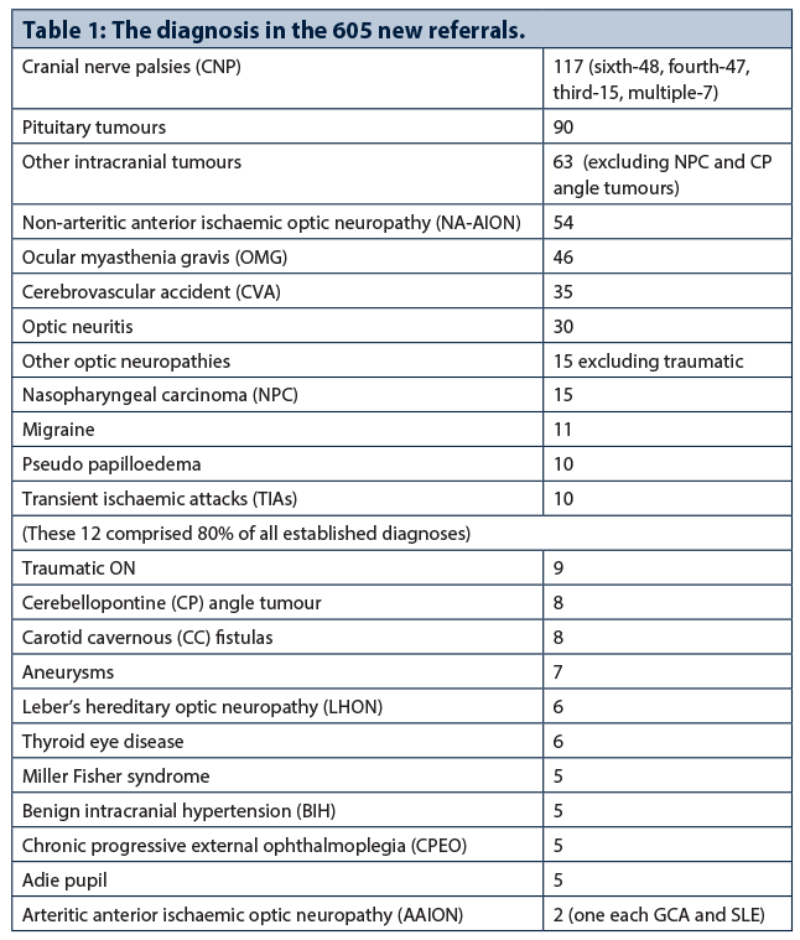

In March 2014 with the arrival of a full-time neuro-ophthalmology fellow (LK Thavaratnam) to our service we were in a position to obtain accurate figures for the incidence of the various conditions seen over the following nine months in one neuro-ophthalmological clinic. During this period 605 new patients were seen and there were a total of 1283 attendances.

Material, methods and results

All patients attending had a full neuro-ophthalmic examination performed including formal perimetry either by Humphrey field analysis or by Goldman perimeter, as indicated following initial examination. This examination was performed by the attached registrar or fellow but all patients without exception were also seen by the senior consultant to confirm the diagnosis and before further investigation or onward referral was arranged. Aside from the diagnoses shown in Table 1 there were 20 other diagnoses of one or two cases each.

Discussion

As can be seen, cranial nerve palsies (CNP) were again the commonest conditions encountered as reported in 2009 from our initial survey carried out in the neuro-ophthalmology clinics of all the public hospitals in Singapore [3].

It should be noted that unexpectedly in our current study fourth nerve involvements were equally common as sixth, which latter palsy is to be expected because of the high incidence of nasopharyngeal cancer in the region. The vast majority of all our CNPs including the fourths were of ischaemic origin and thus expected to recover spontaneously within six to 12 weeks.

Pituitary tumours were the second most commonly seen condition because one of the main neurosurgical referral centres is located in the Singapore General Hospital campus, as is SNEC. We had also arranged for the main neurosurgeon carrying out treatment (usually trans-sphenoidal hypophysectomy) to conduct a weekly session in SNEC alongside our neuro-ophthalmology clinics. Other intracranial tumours were the third commonest condition seen, usually referred from the neurosurgical department. Thus we had a very close association with the neurosurgeons and all the SNEC neuro-ophthalmology staff including attached registrars and fellows attended their weekly neuro-radiological / neurosurgical meeting.

Non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (NA-AION) is the commonest optic neuropathy seen in Singapore [4] and likely to be so in other parts of Asia, associated with the high incidence of diabetes and vascular disease in this part of the world.

Ocular myasthenia gravis (OMG) is also very common and we would expect to have one or two patients in every clinic. This OMG tends to remain ocular, unlike the classical variety seen elsewhere, which is expected to become generalised within two years, yet our OMG can remain purely ocular for many years and even indefinitely. A useful trick in establishing the diagnosis which is mainly from the history is to ask the patient to take a ‘selfie’ in the evening when ptosis develops whereas the ptosis is often absent during the day at clinic times.

Sixty to seventy percent of our optic neuritis (ON) is of the anterior variety rather than retrobulbar often due to an infective cause or of autoimmune cause [5], and not commonly associated with multiple sclerosis, thus quite different from that reported in northern hemisphere patients. It is essential therefore when describing ON to indicate whether it is of the anterior or retrobulbar variety, which is not always made clear especially by non-ophthalmologists.

The incidence of the other conditions listed are more or less the same as would be expected in any neuro-ophthalmology service, except for arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (AAION) associated with giant cell arteritis (GCA) which is rarely seen in southeast Asia thus the condition will be discussed in more detail below.

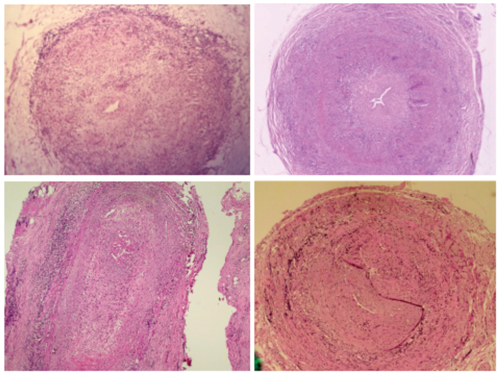

Figure 1: Temporal artery biopsies showing typical pathological features of giant cell arteritis (GCA). The top two are from Edinburgh, the bottom two from Singapore.

AAION and giant cell arteritis (GCA)

As can be seen in the table there were two new cases of AAION diagnosed in the nine month period, only one of which was proven to have GCA on biopsy, the other was due to recurrent systemic lupus (SLE). The prevalence of GCA in the region is extremely low as compared with that reported from the northern hemisphere, and only 12 cases were diagnosed in Singapore (population five million) over 15 years – their details are given in Table 2, but the pathological process as seen in Figure 1 is the same as in the UK. The condition was specifically looked for in all our patients presenting with ischaemic optic neuropathy and central retinal artery occlusion, an urgent erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) being mandatory at presentation. Because of the main author’s extensive experience with GCA in the UK the possibility of other cases being missed is unlikely.

All 12 cases were confirmed by biopsy and over the same period only about the same number of negative temporal artery biopsies were performed. As GCA is so rarely encountered in Singapore, life is in fact made a lot easier for local ophthalmologists dealing with acute visual loss in elderly patients. In all our cases with AAION the optic disc was infarcted pale and swollen at outset as seen in Figure 2. The pathology of this optic nerve infarction in GCA is well illustrated in a 2009 paper by the main author [6].

Figure 2: Fundus photograph shows an infarcted pale oedematous optic disc as in acute arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (AAION). Haemorrhages as shown are not a constant feature.

Variable figures for prevalence of GCA have been reported; in an early 14-year study in the Lothian region of Scotland [7] the incidence was 1.3 cases per 100,000 population per year with 50% having visual or ocular symptoms. In the over 50 year age group the incidence increased to 4.23/100,000/year and now with an older population than in 1979 the prevalence is certainly higher.

A recent study in the Lothian region (population now circa 800,000) revealed that in the five-year period from 2010-2015 723 temporal artery biopsies were performed, of which 158 (21.8%) were positive showing active disease and a further 80 (11.0%) demonstrated suppressed or treated GCA, giving a total of 32.8% positive biopsies. These figures thus show an increase in the incidence of GCA from 10 cases per annum in 1979 to more than four times that number today, thus from expecting to encounter less than one GCA patient per month in the past a case will now present every week in the Lothian region, the explanation of which in the main must be associated with substantial increased ageing of the population in the past 36 years.

Four of our 12 Singapore cases were of the more dangerous occult variety as first described in the UK in 1967 [8], two patients had sequential disease, with one eye already blind at presentation and in both these patients long-term corticosteroid treatment was required [9]. All patients with both classical and occult GCA should be followed up long-term in the eye clinic and not elsewhere, and it is essential that a current ESR result is available at the time of the patient review so this blood test must be arranged prior to the clinic visit [9].

Because of the serious consequences of failure to diagnose GCA as a cause of acute visual loss in the elderly it is one of the commonest eye conditions leading to medical negligence claims in the UK. In all postgraduate ophthalmological examinations, therefore, candidates are invariably questioned regarding GCA but examiners should be aware that those candidates working overseas may have never seen a case and indeed no such patient may have presented to their department with the condition within the standard period of training.

References

1. Cullen JF. 50 Years a consultant in neuro-ophthalmology. Eye News 2013;19:6-9.

2. Cullen JF. Final observations of a European neuro-ophthalmologist in Southeast Asia. Asian J Ophthalmol 2009;11:25-8.

3. Lim SA, Wong WA, Fu E, et al. The incidence of neuro-ophthalmic diseases in Singapore: a prospective study in public hospitals. Ophthalmic Epidemiology 2009;16:65-73.

4. Por YM, Cullen JF. Ischaemic optic neuropathy – the Singapore scene. Singapore Med J 2007;48:246-51.

5. Cullen JF. Optic neuritis in Southeast Asia: a different pattern of disease. Asian J Ophthalmol 2011;12:88-90.

6. Cullen JF. Temporal arteritis 50 years on. Brit J Ophthalmol 2009;93:833-4.

7. Jonasson F, Cullen JF, Elton RA. Temporal arteritis – a 14 year epidemiological clinical and prognostic study. Scot Med J 1979;24:111-7.

8. Cullen JF. Occult temporal arteritis: a common cause of blindness in old age. Brit J Ophthalmol 1967;51:513-25.

9. Cullen JF, Chan Joy, Wong CF, Chew WC. Giant cell (temporal) arteritis in Singapore, an occult case and the rationale of management. Singapore Med J 2010;51:73-7.

Declaration of Competing Interests: None declared.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME