Corneal transplantation (CT) is a significant treatment option for a huge number of patients in the United Kingdom (UK) [1]. For an individual, CT results in a substantial improvement in quality of life. Penetrating keratoplasty with full thickness grafting has been found to increase everyday quality of life by 16.4% with quality-adjusted life year (QALY) of 3.05 years for those with severe keratoconus [2].

Although there is huge individual benefit of CT, there has unfortunately always been a paucity of corneal grafts available in the UK, making this a hugely relevant topic [3]. Despite the well-intentioned Organ Donation Bill (ODB) in 2020, the UK is still behind other countries in the number of people donating their corneas [3]. This piece reviews where the UK stands on CT and suggests what may need to be done to further improve supply to meet ongoing demand.

CT is the most commonly performed allograft transplant in the country [1]. The NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) service control organ and tissue transplantation in the UK and keep careful data on donors, grafts, and transplantation [1]. Despite this, there has been a long-standing supply versus demand issue with availability of corneal grafts lacking [3,4].

The cornea can become damaged over time and infection, distortion, perforation, and scarring can lead to distorted or severely reduced vision [1]. The NHSBT Corneal Activity report demonstrates that over the last 10 years the most common indication for CT is Fuchs Endothelial dystrophy (FED) [4]. In 2021-2022, 50% of CT recipients were over the age of 70 years old at time of surgery and 9.7% of recipients were under the age of 34 [5]. CT can substantially improve the vision of recipients and the improvement of quality of life cannot be overlooked [1,3].

Unlike whole organ donation, tissue such as the cornea is less vulnerable to ischaemia postmortem. Consequently, donor selection can be more considered and there is an opportunity to engage families in the harvesting process [3]. Once harvested and appropriately stored, corneal grafts can be stored in tissue banks and used locally or sent internationally to be used at transplant centres [3]. However, despite this organised chain, there is still demand outweighing supply, leading to significant delay in patients undergoing CT and increasingly long waiting lists [3].

In 2018, 80% of British nationals claimed to support organ donation but only 38% had opted in to the scheme [6]. At the time, uncertainty on how to participate, or concern over the complex administration of signing up, contributed to this. Additionally, agreeing to the concept of organ donation is different to supporting it on an individual basis where the issue becomes more emotional and personal.

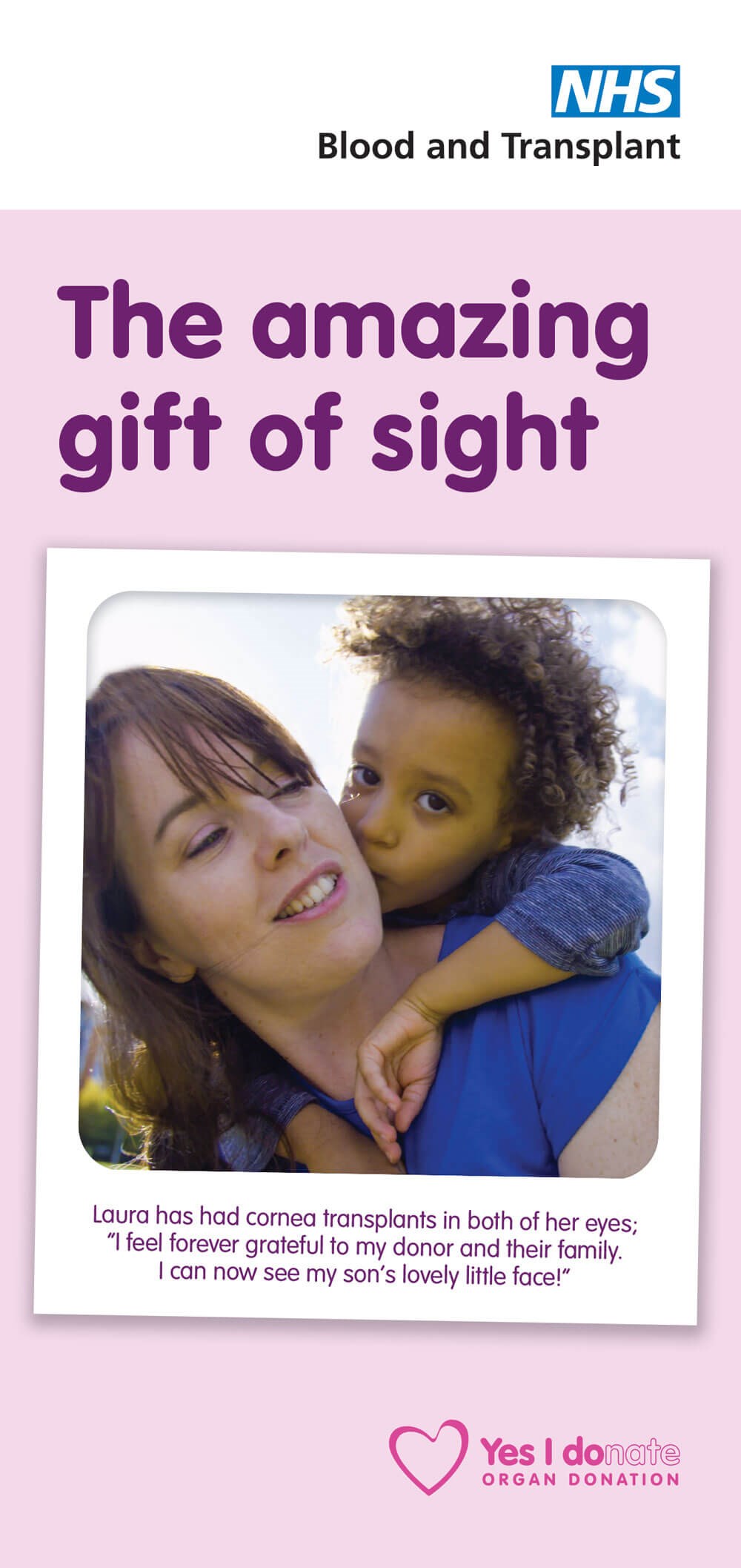

Cornea Transplantation leaflet can be

downloaded and printed from

www.organdonation.nhs.uk/get-involved/

organ-donation-campaigns/

In May 2020 the Organ Donation Bill came into effect, which revolutionised the legal framework surrounding organ donation in the UK [6]. The ‘opt-out’ scheme gives British nationals autonomy over their organs being harvested, while avoiding waste of any potential donors, and in effect it uses inertia to increase the overall supply of organs. It is however acknowledged that the population at large feel uncomfortable about donating their corneas in comparison to other organs [6]. The main contributing factors are the risk of post-harvesting aesthetic causing distress for loved ones, as well as miseducation that the whole eye must always be removed [6]. Much of the population have been misinformed to believe that having a refractive error renders their cornea futile for others [1,6].

In the UK, the year before the ODB came into effect, there were 5,323 corneas donated of which 4,608 were grafted [6]. The tissues that are not grafted may have been harvested for research purpose or due to mechanism of storage in ethanol, the tissue can occasionally become unsuitable for transplant due to degradation [3]. Interestingly, from April 2020-2021 there were only 3,474 corneas donated of which 2,484 were transplanted [5]. This is a significant decrease despite the praised opt-out scheme’s implementation. However, this period coincides with the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic [5]. The start of the pandemic evidently caused complete disarray of normal proceedings in the NHS and data shows that there was significant decrease in harvesting of all organs during this period [1]. A recent study published by Moorfields Eye Hospital shows that there was a 92% reduction in elective corneal surgery during the first five months of the pandemic when compared to the identical period the year before [7]. It could be argued that during this period there was a lack of demand for grafts which was the reason for reduced supply. It is consequently difficult to ascertain the true effect of the opt-out scheme given the unprecedented period which followed its implementation. Interestingly, early data from 2021-2022 shows that donation rates are increasing again [5]. It will be fascinating to observe trends over the next few years to see the true effect of the opt-out scheme on donation rates in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The UK requires an extra 1,500 corneas per annum to meet the demand for transplantation [8]. In the wake of Brexit and the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become even more apparent that relying on importation of health critical goods is a political issue [8]. It can be argued that the UK must look inwardly and work on national policy to improve donor ratings to ensure supply can meet demand from within the country itself.

Spain has the highest organ donation rates in the world while using an opt-out model [4]. Admittedly, it took 10 years for the donation rates to increase in Spain after the opt-out policy came into effect [4]. This however is not felt to be the root of their landslide success. Since 1991, Spain has established a network of transplant co-ordinator teams (TCTs) that organise each step of donation in hospitals nationally [4,9]. TCTs are responsible for local and regional education so that the general population are more widely versed on the process of donation and as a result can make an informed decision on opting out [4,9]. The Spanish have adopted their own ‘hybrid’ model where after death, families are involved in the decision-making process [4]. This investment into identification of donors, discussion with their family and education of the public has been vital to donation rates surpassing those of other countries [4]. This begs the question: should Britain think about doing the same? Education may well be the key to increasing donor rates, and if so, utilising points of interaction with the health service would be a good opportunity to discuss tissue donation. This could include GP appointments, antenatal bookings and visits to Accident and Emergency throughout an individual’s life.

The world of corneal transplantation is ever changing and there are significant advances in technology occurring. There is movement towards using different surgical technique to avoid requiring tissue grafts at all. The Descemet’s stripping only (DSO) method is an example of this, where the regenerative nature of the corneal endothelium is utilised for patients [10]. Cells are stripped away and endothelial cells migrate to fill the area, avoiding the need for a graft [10]. This method has been successful for patients with Fuchs dystrophy [10].

Alternatively, there are also advances being made into synthetic corneas. The CorNeat KPro is an innovative idea to use a polymeric scaffold implant. There has recently been one successful graft in a human with postoperative visual acuity at one year being maintained. The Endo Art implant is also a bio-compatible polymer implant which has had some surgical success so far [11]. These success stories may indicate a change in surgical options available, which may avoid the necessity of human tissue partially, or eventually even completely [12].

One of the other significant advances in corneal surgery over the years is the movement away from full thickness grafting and instead practising selective replacement of only the diseased corneal tissue [13]. These selective grafting techniques have given rise to the potential for one donor cornea to be used in multiple recipients. One success story used the anterior lamellar in a patient with macular corneal dystrophy, the posterior lamellar for a patient with pseudophakic bullous keratopathy, and lastly, limbal stem cells were transplanted in a child who was deficient [13]. The literature reports that splitting the corneal tissue can benefit up to five other patients [14]. Evidently, if this technique was to become more commonplace, it would significantly improve the supply versus demand issue, and the donation of one cornea could improve multiple peoples’ quality of life. However, the ethical conversation around informed consent cannot be ignored. One donor's tissue being used for multiple patients, potentially in various parts of the world, may require a more robust legal framework than there is currently in place. Complex questions of whether the donor is allowed to choose whether their cornea is separated, or regulation of whether tissue is allowed to be separated to be used internationally would need to be carefully thought out. From the donation perspective, the public may be more inclined to donate if educated that their tissue could benefit multiple peoples’ lives.

There is an argument to say that new technology will begin to improve the supply versus demand issue we currently face. Whether this is due to new surgical techniques such as DSO and selective corneal grafting, or if eventually artificial grafts negate the need for human donation, there is still a long period ahead where human tissue remains the mainstay of treatment. To achieve this, we must strive to make the conversation around organ and tissue donation more commonplace to give an opportunity for the public to ask questions and gather information. As per the Spanish model, the involvement of family is key to increasing donation after the death of a suitable donor. It could be argued that lacking donation in the British public is more an issue of lacking information and education rather than whether the public must opt-in or out. It will become apparent over the next few years as to whether the opt-out scheme itself will increase supply, or, if this battle, as many before, will only be won through better public education.

References

1. About cornea donation. NHS Organ Donation.

https://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/

helping-you-to-decide/about-organ-donation/

what-can-you-donate/about-cornea-donation/

2. Roe RH, Lass JH, Brown GC, Brown MM. The value-based medicine comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus. Cornea 2008;27(9):1001-7.

3. Gaum L, Reynolds I, Jones M, et al. Tissue and corneal donation and transplantation in the UK. Br J Anaesth 2012;108:i43-7.

4. Etheredge H. Assessing global organ sonation policies: opt-in vs opt-out. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2021;14:1985-98.

5. Transplant activity report. NHS Organ Donation.

https://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/

helping-you-to-decide/about-organ-donation/

statistics-about-organ-donation/transplant-activity-report/

6. Dimitry M, Lee H. Recent change in law and corneal transplantation in the UK. Eye 2020;35(5):1524-5.

7. Din N, Phylactou M, Fajardo-Sanchez J, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on acute and elective corneal surgery at moorfields eye hospital london. Clin Ophthalmol 2021;15:1639-5.

8. Romano V, Dinsdale M, Kaye S. Compensating for a shortage of corneal donors after Brexit. The Lancet 2019;394(10200):732.

9. Matesanz R, Miranda B, Felipe C. Organ procurement in Spain: impact of transplant coordination. Clin Transplant 1994;8(3 Pt 1):281-6.

10. Cornea Research Foundation of America - Descemet's Stripping Only (DSO).

http://www.cornea.org/Learning-Center/

Descemet-s-Stripping-Only-(DSO).aspx.

11. Lapid-Gortzak R, Auffarth G. A New Type of Corneal Availability. The Ophthalmologist.

https://theophthalmologist.com/

subspecialties/a-new-type-o

f-corneal-availability#

12. Bahar I, Reitblat O, Livny E, Litvin G. The first-in-human implantation of the CorNeat keratoprosthesis. Eye (Lond) 2022. Epub ahead of print.

13. Vajpayee RB, Sharma N, Jhanji V, et al. One donor cornea for 3 recipients: a new concept for corneal transplantation surgery. Arch Ophthalmol 2007;125(4):552-4

14. Gadhvi KA, Coco G, Pagano L, et al. Eye banking: one cornea for multiple recipients. Cornea 2020;39(12):1599-1603.

[All links last accessed July-August 2022].

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME