Further to my last article in Eye News (print issue) describing the diagnostic approaches to various clinical scenarios in glaucoma, the approach to angle-closure glaucoma (ACG), a situation terrifying for patient and registrar alike, will be discussed. Please refer to the previous article on the approach to postoperative trabeculectomy complications for a discussion on the utility of classification and algorithmic approaches in medicine and ophthalmology (Eye News 2016;23(2):42-4).

Presentation

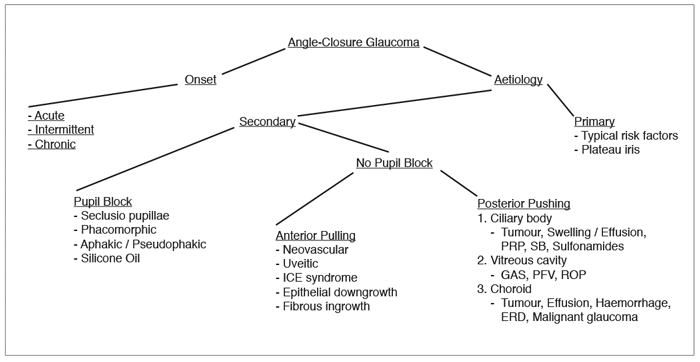

The patient with ACG is often thought of as presenting with acute, painful, unilateral loss of vision, seeing coloured haloes, suffering from nausea and vomiting, and having a fixed, mid-dilated pupil, corneal oedema, and a shallow anterior chamber (AC) in a phakic eye with high intraocular pressure (IOP) and a closed angle on gonioscopy. Certainly, this represents one of the most dramatic presentations in the field of glaucoma, and one every ophthalmologist should be able to recognise and treat expeditiously. However, ACG offers a much richer and diverse experience, from the sudden and dramatic to the slow and mundane. Both situations, however, are capable of resulting in significant loss of optic nerve function. As previously discussed, an organised approach will save time and stress as one arrives at a diagnosis, from which point appropriate decisions can be made (Figure 1). Fundamental to the diagnosis of the conditions below is skillful indentation and non-indentation gonioscopy (see resources below).

Figure 1: Angle-closure glaucoma algorithm.

ICE: iridocorneal endothelial. PRP: panretinal photocoagulation. SB: scleral buckle.

PFV: persistent fetal vasculature. ROP: retinopathy of prematurity. ERD: exudative retinal detachment.

Classification and algorithm

My initial classification of ACG involves two features: onset and aetiology. Onset is described as acute, intermittent or chronic. The above case description exemplifies acute ACG. The dramatic presentation of reduced vision, painful red eye, corneal oedema, headache, nausea and vomiting are a result of the acute, sudden rise in IOP. If bouts of acute angle closure are less severe and self-resolving, this is termed intermittent ACG. The IOP is normal between episodes, with less severe versions of the above symptoms spontaneously resolving. Examination clues include a narrow angle on gonioscopy and evidence of previous episodes of acute ACG: glaucomflecken, iris atrophy, zonule laxity. In cases of slow, gradual angle closure by either apposition or development of peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS) (differentiated by indentation gonioscopy), the IOP may be only slightly raised, but usually with evidence of significant glaucomatous optic nerve damage. This represents chronic ACG.

The first branch in the aetiological approach to ACG differentiates primary and secondary causes. In the former, the closed angle is due to a constellation of predisposing risk factors in the absence of a definite secondary cause. The risk factors for primary ACG include a small anterior segment (hyperopia, nanophthalmos, microphthalmos, microcornea), shallow AC (usually less than 2-2.5mm), family history of primary ACG, anterior iris insertion in certain ethnic groups and iris configurations, and the absence of adequate iris decongestion during mydriasis. Plateau iris is usually categorised under the primary category. In plateau iris configuration, an anterior iris insertion and anteriorly positioned ciliary processes result in a characteristic plateau appearance on gonioscopy, despite a patent iridotomy. If a patient with plateau iris configuration suffers from episodes of ACG with high IOP, this is called plateau iris syndrome, and can be treated with miosis, laser iridoplasty or endocyclophotocoagulation of the anterior ciliary processes.

“ACG...represents one of the most dramatic presentations in the field of glaucoma, and one every ophthalmologist should be able to recognise and treat expeditiously.”

In secondary ACG, there is a defined reason or cause of the angle closure. Trainees are often tempted to proceed directly to the 'anterior pulling versus posterior pushing' causes of secondary ACG, bypassing an important preceding step in our algorithm: pupil block. In pupillary block, there is obstruction to the flow of aqueous between the posterior and anterior chambers, resulting in a pressure gradient behind the iris and leading to angle closure. Treatment generally involves creating an iridotomy / iridectomy for an alternate path of aqueous flow, or addressing the native or synthetic intraocular lens. Seclusio pupillae involves 360 degrees of posterior synechiae, completely occluding aqueous flow. Phacomorphic pupillary block, strictly speaking, is due to any pupil block where the native lens is thought to have a major role.

However, it usually refers to an intumescent lens and / or anterior displacement of the lens. This can occur in cases of zonular laxity or frank lens dislocation. Aphakic and pseudophakic pupil block can occur from adhesions between the iris and the remaining capsule, intraocular lens or anterior hyaloid face. Intraocular lens malposition, or inadvertent reversed insertion of a posteriorly vaulted lens, can also result in pseudophakic pupil block. Finally, in cases of retinal surgery where a silicone oil fill remains in the eye, the oil can obstruct the normal flow of aqueous in aphakic and, occasionally, pseudophakic cases. A peripheral iridectomy remedies this situation, but uniquely must be created inferiorly due to silicone oil’s lower specific gravity than aqueous (resulting in aqueous fluid accumulation inferiorly in the posterior chamber).

If a pupil block situation has been ruled out, the algorithm proceeds to the aforementioned anterior pulling / posterior pushing branches. In anterior pulling mechanisms, a cohesive and subsequently cicatricial force within the iridocorneal angle serves to close it, resulting in PAS seen on gonioscopy. Depending on one’s practice, the most common causes are neovascular / rubeotic glaucoma and inflammatory / uveitic causes. Neovascular causes broadly include vascular, inflammatory / infectious, neoplastic and iatrogenic causes, with the most common being proliferative diabetic retinopathy. With respect to uveitis, one of its major mechanisms for causing visual loss is from secondary glaucoma.

Again, this can be approached by way of secondary open-angle causes (trabeculitis, debris, chronic damage to trabecular apparatus, steroid-induced), secondary ACG (acute: ciliary body inflammation; subacute: seclusio pupillae; chronic: PAS), and mixed mechanisms. As such, chronic uveitis can result in an anterior pulling mechanism of secondary ACG. Finally, more rare causes of secondary anterior pulling ACG include angle closure from abnormal contractile cells invading the angle. These include abnormal endothelial cells in the iridocorneal endothelial (ICE) syndrome, epithelial cells in epithelial downgrowth, and fibroblasts in fibrous ingrowth.

In posterior pushing secondary ACG, an anteriorly-directed force behind the iris serves to close the angle. These causes can be divided into those from the ciliary body, vitreous cavity and choroid. Ciliary body tumours can exert a mass effect, thereby causing either a localised or diffuse ACG, depending on the extent of the lesion. Ciliary body swelling and effusions can also cause a mass effect, but often are thought of causing posterior pushing ACG from anterior rotation, forward displacement of the lens-iris diaphragm and subsequent angle closure. Causes include uveitis, heavy panretinal photocoagulation, a tight scleral buckle, and sulfonamide medications (most notoriously topiramate, a sulfamate).

For the vitreous cavity, a gas overfill after vitreoretinal surgery or pneumatic retinopexy can cause ACG. Persistent fetal vasculature and retinopathy of prematurity can cause secondary ACG due to contractile retrolental tissue. For choroidal causes, a large choroidal tumour, effusion, haemorrhage or exudative retinal detachment can all cause posterior pushing ACG by way of mass effect. Malignant glaucoma is also included here due to theories regarding its cause secondary to acute choroidal expansion and subsequent pressure gradients between the posterior and anterior segments causing forward displacement of the ciliary body-lens-iris complex. Malignant glaucoma can thus be included in any portion of the posterior pushing category that serves to remind the user, as long as it is indeed remembered.

Conclusion

Figure 1 depicts the algorithm to ACG and is a useful figure to commit to memory. It offers a simple approach that concludes with a small number of diagnostic options based on careful examination techniques. Not only will this prove useful at the slit-lamp, but similar to our previous algorithm will provide a clear and elegant approach to such a case in the examination scenario. As always, the more a memory aid is customised to ones own preferences, the more effective it will be, and is thus encouraged.

Further reading

-

Damji KF, Freedman SF, Moroi SE, et al (editors): Shields Textbook of Glaucoma, Sixth Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

-

Quigly HA. Angle-closure glaucoma-simpler answers to complex mechanisms: LXVI Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol 2009;148:657-69.

-

Gonioscopy.org: www.gonioscopy.org

Last accessed July 2016.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME