Neuro-ophthalmology is a complex and difficult subspecialty in ophthalmology. It has several connections to neurology, neuro-surgery, rheumatology as well as many other medical specialties. Working in an multidisciplinary team (MDT) environment is key to success in this subspecialty as mistakes can lead not only to increased morbidity but also to mortality.

Over two articles (Part 2 is available here) I will discuss several clinical scenarios, the importance of identifying these cases and the need for urgent investigations and treatment.

Case 1

An elderly 77-year-old female presented to a nearby hospital emergency clinic with a few days history of horizontal and vertical diplopia and right upper lid ptosis. She was seen by the consultant on call and, following orthoptic assessment, it was felt that she had partial right III cranial nerve (CN) palsy. As she was not having any significant pain, no pupil involvement was noted and she was looking frail, she was diagnosed with microvascular right III CN palsy. She had basic blood test which was normal and was given a follow-up in six weeks for orthoptic assessment. The next morning the patient collapsed with severe headaches and was taken to hospital where she was diagnosed with a subarachnoid haemorrhage from a burst aneurysm. She had urgent neuro-surgical intervention and survived with permanent complete right III CN palsy.

Comment: Microvascular cranial nerve palsies are diagnoses of exclusion. All III CN palsies need MRA or CTA depending on availability. Partial III CN palsies can develop over days to involve pupil and even complete III CN palsy which is pupil sparing could harbour an aneurysm in 10% of cases.

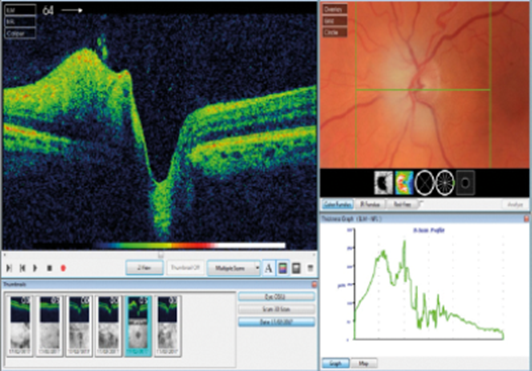

Figure 1: Swollen left optic nerve in an elderly patient with a non-crowded optic nerve.

Case 2

An elderly 75-year-old male presented to the emergency clinic following being referred by his local optician. He saw his optician with a complaint of a large scotoma in the field of his left eye, noted to have a swollen left optic nerve and sent urgently to the hospital (Figure 1). On examination he was found to have swollen left optic nerve with reduced visual acuity (0.2 Log MAR) and left relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD). Fundoscopy of the right eye was normal with healthy optic nerve (C/D ratio 0.5) and visual acuity of 0.1 Log MAR. He had no headaches or tender temples and there was no jaw claudication or systemic concerns. His medical history included investigation for iron deficiency anaemia. He had blood tests for ESR, CRP, FBC, glucose and lipids, as well as a request for an MRI head scan. He was given a diagnosis of non arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (NAION) and discharged from the emergency clinic. His blood test came back showing raised ESR and CRP with anaemia on FBC. No action was taken on the results but the patient presented to the emergency clinic two days later with visual acuity of hand motion (HM) and full blown swollen optic nerve. He was diagnosed with giant cell arteritis (GCA) causing right arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (AAION) which was confirmed on the temporal artery biopsy (TAB). He was treated with high dose steroids and referred to rheumatology for monitoring and tailoring of his steroid treatment.

Comment: Silent GCA can happen and lead to severe visual loss without any significant systemic features. It is really important to have high suspicion levels in any unilateral swollen optic nerve in elderly patients and check inflammatory markers with appropriate action taken on the results. NAION is extremely rare to happen in non-crowded optic nerves (C/D was 0.5 in the right eye).

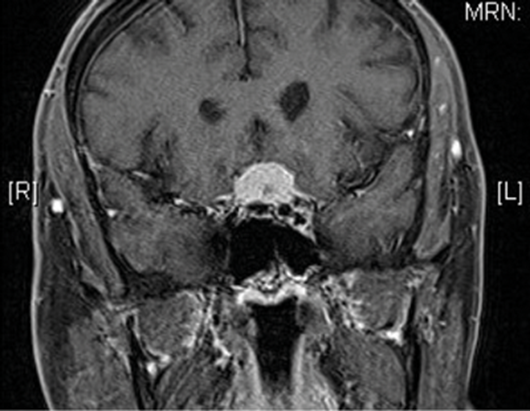

Figure 2: Large pituitary lesion compressing the left optic nerve and chiasm.

Case 3

A 35-year-old male presented to our emergency clinic with a history of acute reduction of vision in his left eye. He did not have any medical or ophthalmic history. He had a fall with head trauma a few weeks earlier. No loss of consciousness was documented and no hospitalisation was needed at the time. On assessment, his vision was down to perception of light (PL) in his left eye with RAPD. Fundus examination was unremarkable in both eyes. He was felt to have left optic neuritis or traumatic optic neuropathy following the head trauma (although this was considered as unlikely as happened two weeks earlier and was felt to be minimal). Before considering offering steroid treatment, the patient underwent urgent neuro-imaging which unexpectedly showed a large pituitary lesion compressing the left optic nerve (Figure 2).

He was referred for urgent neuro-surgical opinion and had surgical intervention. This resulted in improvement of his visual functions in his left eye.

Comment: Brain tumours could present in various ways. Detailed history is extremely important in neuro-ophthalmology and when something does not fit or you have suspicions, clinicians need to arrange neuro-imaging. Pituitary lesions, especially adenomas, could bleed (pituitary apoplexy), which could lead to sudden expansion of the lesion and sudden change in visual functions. This could happen following pregnancy, trauma and major surgery.

Case 4

An elderly 76-year-old male presented to the emergency clinic after being seen by his optician routinely. His optician noted a homonymous visual field loss. The patient is a known vasculopath with hypertension and diabetes in his medical background. Automated field test confirmed right sided homonymous hemianopia. The patient denied any previous strokes. He was given 300mg of Aspirin and put on 75mg clopidorgel and urgently referred to the local stroke service for further assessment. He went on to have neuro-imaging and carotid Doppler and found to have an occipital lobe infarct.

Comment: Homonymous hemianopias (HH) are cerebral vascular accident (CVA) or tumour until proven otherwise. They should be treated with the same urgency as any other stroke. The same should apply to amaurosis fugax cases. TIAs carry around 10% risk of developing CVA if not investigated and risk factors controlled and, in theory, the same applies to amaurosis fugax. The ABCD2 score helps guide to the urgency of stroke appointment.

In the next article, further cases will be discussed with a summary of the cases that makes neuro-ophthalmology challenging but also interesting.

Further reading

1. Miller MR, Newman NJ, Biousse V, Kerrison JB: Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-ophthalmology – The essentials. 2nd edition. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007.

2. Kline LB: Neuro-ophthalmology – Review Manual. 6th edition. Slack inc.; 2007.

3. Pane A, Miller NR, Burdon M: The Neuro-ophthalmology Survival Guide. Mosby; 2007.

4. RCOphth Unmissables Seminar. March 2017.

Acknowledgment

This article is based on a training day at the Royal College of Ophthalmologists in 2017 run by Susan Nollan and Tim Matthews.

Part 2 of this topic is available here.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME