IMGs in the NHS

The General Medical Council (GMC) defines an international medical graduate (IMG) as someone who has obtained their primary medical qualification outside the European Economic Area (EEA) [1], meaning that an IMG is a medical doctor whose initial medical degree was earned in a country or region that is not part of the EEA.

In contrast, the Royal College of Ophthalmologists (RCOpth) characterises an IMG as someone who, regardless of where they acquired their primary medical qualification, does not have the right of indefinite residence or is not settled in the UK, as determined by immigration and nationality laws [2]. For the purposes of this article, we will adhere to the GMC definition.

The NHS, established 75 years ago, has long relied on IMGs to be able to meet its needs. Currently, IMGs make up 32.9% of doctors within the NHS. Between 2017 and 2021, while the rate of UK medical graduates entering the workforce increased by a modest 2%, IMGs entering the workforce experienced a substantial surge of 121%. In 2017, UK graduates made up slightly more than half (53%) of new doctors joining the workforce, while IMGs accounted for nearly a third (32%). If these trends continue until 2030, UK graduates are projected to comprise just over a quarter (26%) of those joining the workforce, with IMGs constituting over two-thirds (67%) [3].

The quality of life, safety and work-life balance in the UK make it an attractive destination for IMGs. Furthermore, the chance to work within the NHS, a universal healthcare system, presents IMGs with abundant opportunities for personal and professional growth. However, it’s important to acknowledge the challenges faced by IMGs globally, such as a potential loss of autonomy in decision-making, professional devaluation, a higher rate of complaints and assessment biases [4-6].

It’s concerning to note that a significant number of specialty and specialist doctors (SAS) and locally employed doctors in the UK, many of whom are IMGs, have reported instances of bullying or harassment in their workplaces [7]. New strategies have been developed to address and solve these obstacles. Such as IMG local and national induction programmes, focused support and mentoring for IMGs, and encouragement of IMG representation on college bodies.

Shortage of ophthalmologists

In 2021, Public Health England highlighted that England had about 2.5 consultant ophthalmologists per 100,000 population, which falls short of the recommended range of 3 to 3.5 specialists per 100,000. To reach that minimum recommendation, an additional 250 consultant ophthalmologists would be needed [8]. This challenge was further aggravated after the final COVID-19 restrictions were lifted as the pandemic had caused a significant decrease in cataract procedures and ophthalmology outpatient visits, leading to a substantial backlog of care. Moreover, ophthalmology had the third highest leaving rate after gaining the Certificate of Completion of Training (CCT) as well as the highest leaving rate two and three years after gaining CCT than any other specialty [3]. Consequently, the demand for ophthalmologists in the UK has surged. The country requires specialists at a pace that exceeds its ability to produce them locally, creating numerous opportunities for IMG ophthalmologists to work in the UK.

Different pathways to practice ophthalmology in the UK

To become a consultant ophthalmologist in the UK, you must be on the GMC specialist register. This can be accomplished through various routes. The first route involves completing the full seven-year UK ophthalmology training programme, leading to the award of a CCT in ophthalmology. Alternatively, if someone does not complete any part of the official seven-year programme, they can still achieve recognition as a consultant by providing evidence of equivalent experience and training. This experience and training can originate from overseas, the UK or a combination of both and is referred to as the CESR pathway, which stands for Certificate of Eligibility for Specialist Registration. From 30 November 2023, this route will go through some changes and likely to be renamed as the portfolio route.

The Royal College of Ophthalmologists has introduced a new, competency-based Ophthalmic Specialist Training (OST) programme scheduled to commence in August 2024. In order to facilitate this transition, starting from 2024, entry into OST will only be available at the year one (ST1) level. The last opportunity for entry at the ST3 level was in August 2023. Candidates with over 30 months of ophthalmology experience will be required to consider the CESR (portfolio) route to attain specialist registration [9].

Some people may aspire to complete a fellowship in the UK and return to their home country. However, it’s important to note that this also requires GMC registration. There are several pathways to obtain GMC registration. The most popular route is through the Professional and Linguistic Assessments Board (PLAB) exam which is designed for doctors who have completed their internship. Those who have completed specialised ophthalmology training have an alternative to bypass the PLAB by successfully passing either the FRCS Glasgow (Ophth) or FRCS Ed (Ophth) exams, which grants them registration with the GMC. Other avenues for GMC registration include passing the FRANZCO exams or opting for RCOphth Dual Sponsorship [10].

According to the Royal College of Ophthalmologists, due to the recent modifications in the OST curriculum, it is anticipated that there will be reduced demand for post-CCT fellowships by UK trainees. This is because they will now have the opportunity to gain Special Interest Areas (SIAs) experience before completing their CCT. Consequently, there will be increased availability for post-CCT fellowships for non-UK trainees [9].

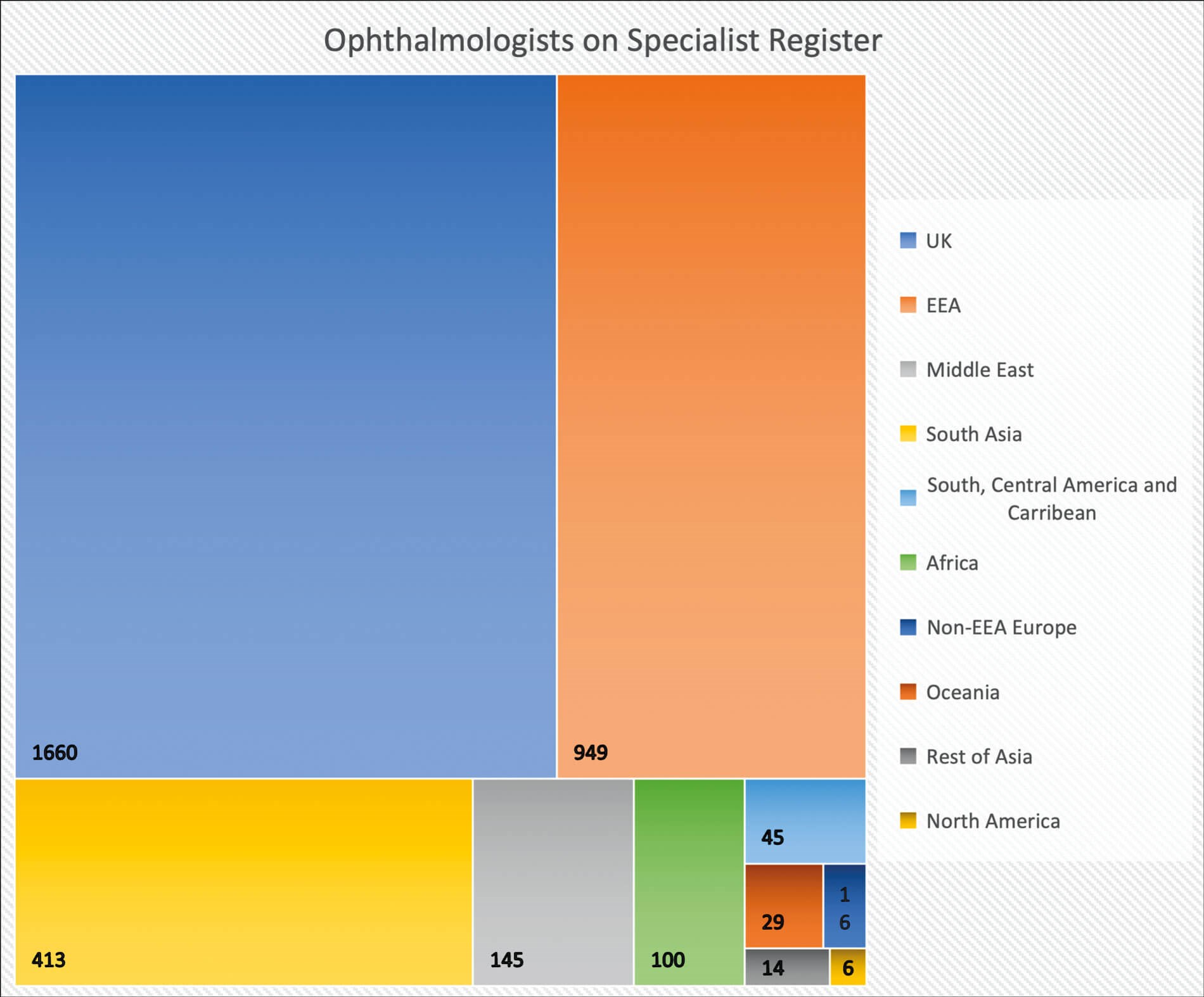

Figure 1: Distribution of specialist ophthalmologists based on place of primary medical qualification.

IMGs in ophthalmology

Currently, there are 3377 ophthalmologists on the specialist register in the UK. 49.2% of which are UK graduates, 28.1% are EEA graduates and 22.7% are IMGs. The distribution of specialist ophthalmologists based on their place of primary medical qualification is shown in Figure 1. The largest portion of specialist ophthalmologists are UK graduates, totalling 1660. Following this, there are 304 ophthalmologists from India, 227 from Greece and 140 from Italy [11].

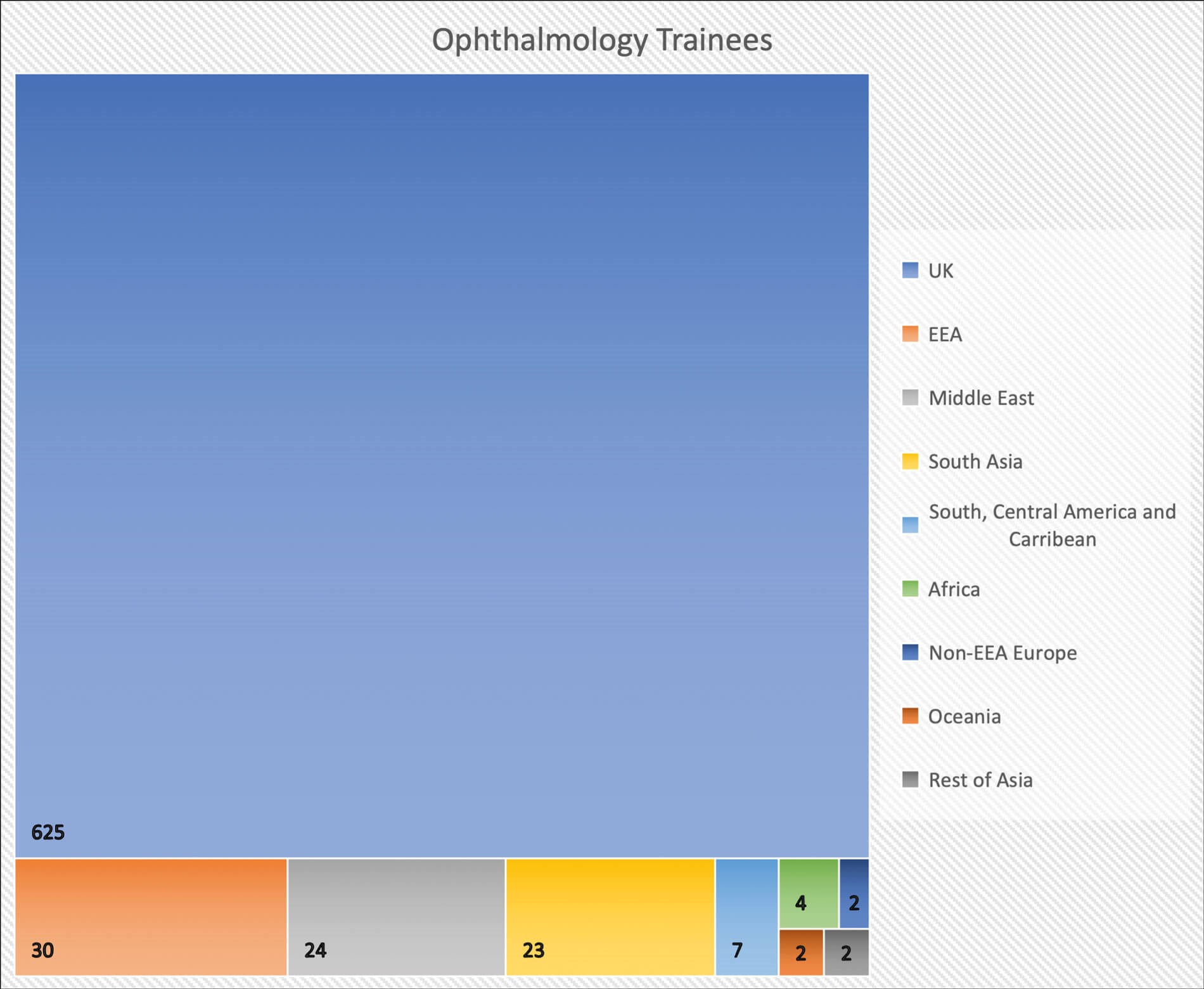

Figure 2: Distribution of ophthalmology trainees based on place of primary medical qualification.

Out of the 719 current ophthalmology trainees, only 8.9% are IMGs and 4.2% are graduates from the EEA. Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of ophthalmology trainees based on their place of primary qualification, with India contributing the highest number of IMG trainees at 15, followed by Egypt with 12 trainees. Notably, IMG ophthalmology trainees have an equal male-to-female ratio [12]. It’s worth noting that, in all specialty training programmes, except ophthalmology, the largest ethnic group was White. However, in ophthalmology, the largest group of trainees belongs to the Asian or Asian British ethnic background [3].

Out of all ophthalmology trainees, IMGs formed 15% in 2013. This has steadily dropped to 8.9% in 2023. This can be partially explained by the increase in competition to enter ophthalmology specialty training with competition ratio reaching 9.91 this year [13]. Additionally, IMGs have shown a trend of occupying a larger share of non-training posts, as they make up 60% of non-consultant and non-training doctors currently working in the UK [14].

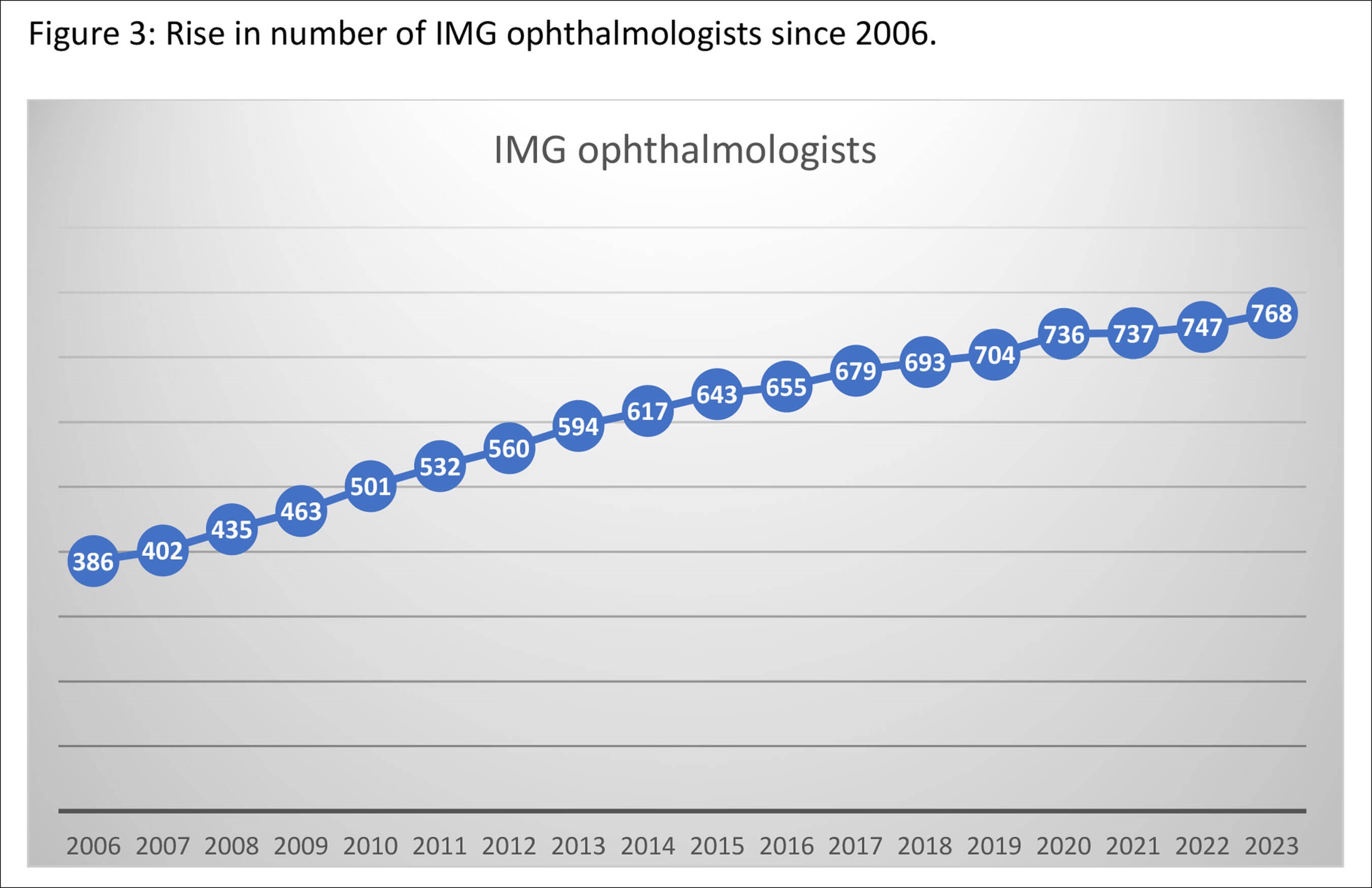

Figure 3: Rise in number of IMG ophthalmologists since 2006.

Why ophthalmology in the UK?

There has been an increased interest in pursuing ophthalmology in the UK. Notably, the number of IMG consultants is steadily increasing as shown in Figure 3. There has also been a significant rise in the number of applicants for OST, reaching 971 this year [13]. This international appeal is evident by the fact that 50% of candidates taking the FRCOphth online written exams are now from overseas [15].

The increasing influx of IMGs into the field of ophthalmology in the UK can be attributed to various factors. One key element is the inclusion of all medical practitioners on the Shortage Occupation List in the UK since 6 October 2019. This means that all medical practitioners are exempt from the Resident Labour Market Test and can apply for round one of specialty training. Furthermore, OST is an attractive option for many IMGs. It offers a seven-year run-through programme, making it the longest of its kind globally. However, this extended training duration mandates the greatest number of surgical procedures and the greatest number of objective competency assessments of surgical and procedural skills, which many IMGs find appealing. Moreover, UK ophthalmology training is rated highly, with an overall satisfaction rating of 86.5% [16].

Conclusion

Current data underscores the evolving landscape of ophthalmology in the UK, with a noticeable rise in the number of IMG specialist ophthalmologists. Conversely, there is a steady decline in the presence of IMG ophthalmology trainees. These trends not only indicate the field’s attractiveness to IMGs but also emphasise the heightened competition for specialty training positions and the evolving pathways through which IMGs can practice ophthalmology in the UK.

References

1. Working and Training in the NHS 2021. NHS Employers.

https://www.nhsemployers.org/

system/files/media/Working-and

-training-in-NHS-2021_0.pdf

2. Working in the UK. Royal College of Ophthalmologists.

https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/

our-work/ophthalmology-careers/

working-in-the-uk

3. Workforce Report 2022 - Full Report. General Medical Council.

https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/

documents/workforce-report-2022

---full-report_pdf-94540077.pdf

4. Chen PG, Nunez-Smith M, Bernheim SM, et al. Professional experiences of international medical graduates practicing primary care in the United States. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25(9):947-53.

5. Wong A, Lohfeld L. Recertifying as a doctor in Canada: international medical graduates and the journey from entry to adaptation. Med Educ 2008;42(1):53-60.

6. Woolf K, Rich A, Viney R, et al. Perceived causes of differential attainment in UK postgraduate medical training: a national qualitative study. BMJ Open 2016;6(11):e013429.

7. SAS and Locally Employed Doctors Survey Initial Findings Report. General Medical Council.

https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/

sas-and-le-doctors-survey-initial-findings

-report-060120_pdf-81152021.pdf

8. Coming Up Short. The Ophthalmologist.

https://theophthalmologist.com/

business-profession/coming-up

-short#:~:text=In%202021%2C

%20Public%20Health%20England,

additional%20250%20consultant%

20ophthalmologists%20today

9. Royal College of Ophthalmologists Training Information. Royal College of Ophthalmologists.

https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/training/

ophthalmic-specialist-training/ost-curriculum/

curriculum-2024/curriculum-2024

-frequently-asked-questions-2/

10. The Savvy IMG Ophthalmology Guide to the UK. The Savvy IMG.

https://thesavvyimg.co.uk/

ophthalmology-guide-uk/#:~:

text=Before%20you%20can%

20start%20UK,can%20be%

20in%20any%20specialty

11. General Medical Council Data Reports. General Medical Council.

https://data.gmc-uk.org/gmcdata/home/#/reports/

The%20Register/Stats/report

12. General Medical Council Data Reports. General Medical Council.

https://data.gmc-uk.org/gmcdata/home/

#/reports/Postgraduate%

20training/Stats/report

13. Competition Ratios 2023. Health Education England.

https://medical.hee.nhs.uk/medical-training

-recruitment/medical-specialty-training/

competition-ratios/2023-competition-ratios

14. The state of medical education and practice in the UK: the workforce report (2019). General Medical Council.

https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/

documents/the-state-of-medical-education

-and-practice-in-the-uk---workforce-report

_pdf-80449007.pdf

15. RCOphth 2022 Annual Report (2022). Royal College of Ophthalmologists.

https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/

uploads/2023/05/RCOphth-2022

-Annual-Report-FINAL-1.pdf

16. Training environments 2018: key findings from the national training surveys (2018). General Medical Council.

https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/

documents/training-environments

-2018_pdf-76667101.pdf

[all links last accessed October 2023]

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME