Wolfram syndrome 1 (WS1) was first described by Wolfram and Wagener in 1938 and it’s a rare neurodegenerative, progressive disorder, also known as DIDMOAD (diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy, and deafness) [1]. We present an atypical case of WS with a delayed diagnosis of several decades.

Case report

A 47-year-old female was incidentally discovered to have colour vision impairment during her son’s routine eye examination. On further questioning, the patient mentioned having impaired vision since childhood, attributed to amblyopia, and has been wearing myopia correction since early adulthood. She also reported mild hearing impairment and chronic insomnia. Otherwise, she was fit and healthy and on no regular medications. The father and paternal uncle of the patient have optic nerve disease with a possible diagnosis of glaucoma and the mother is a type II diabetic.

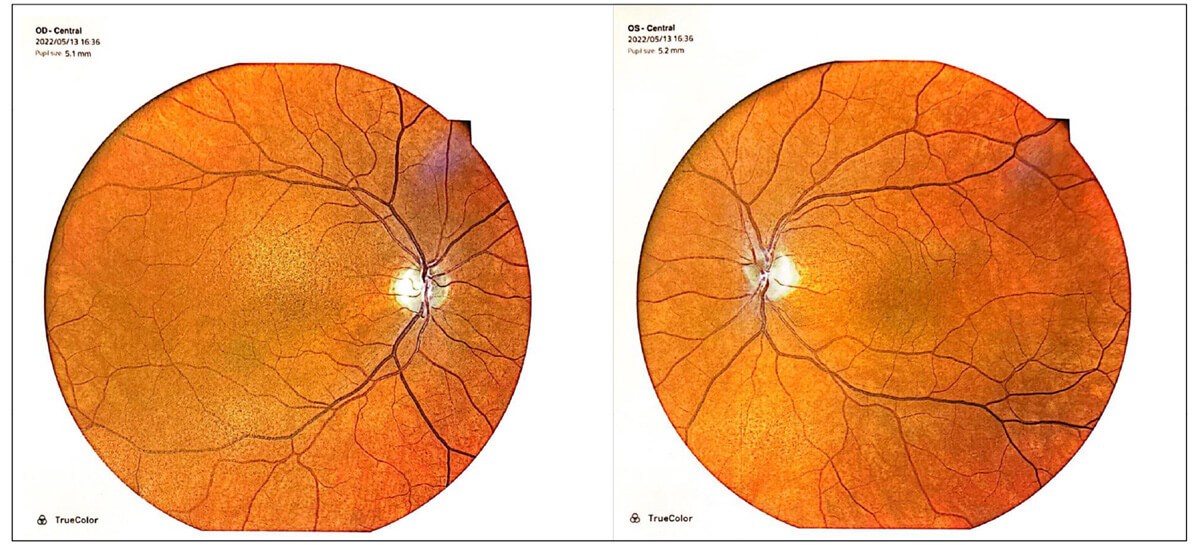

Figure 1: Fundal imaging showing bilateral pigmentary maculopathy and disc pallor.

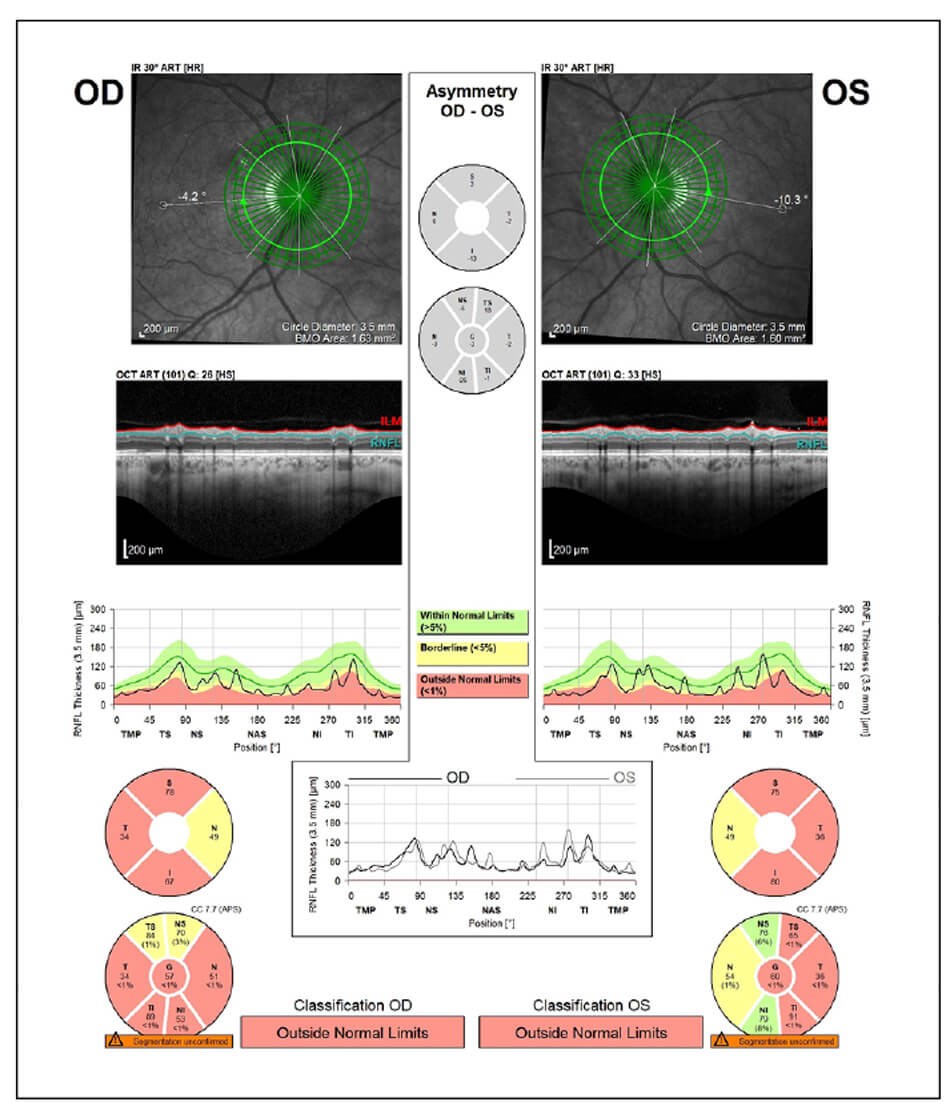

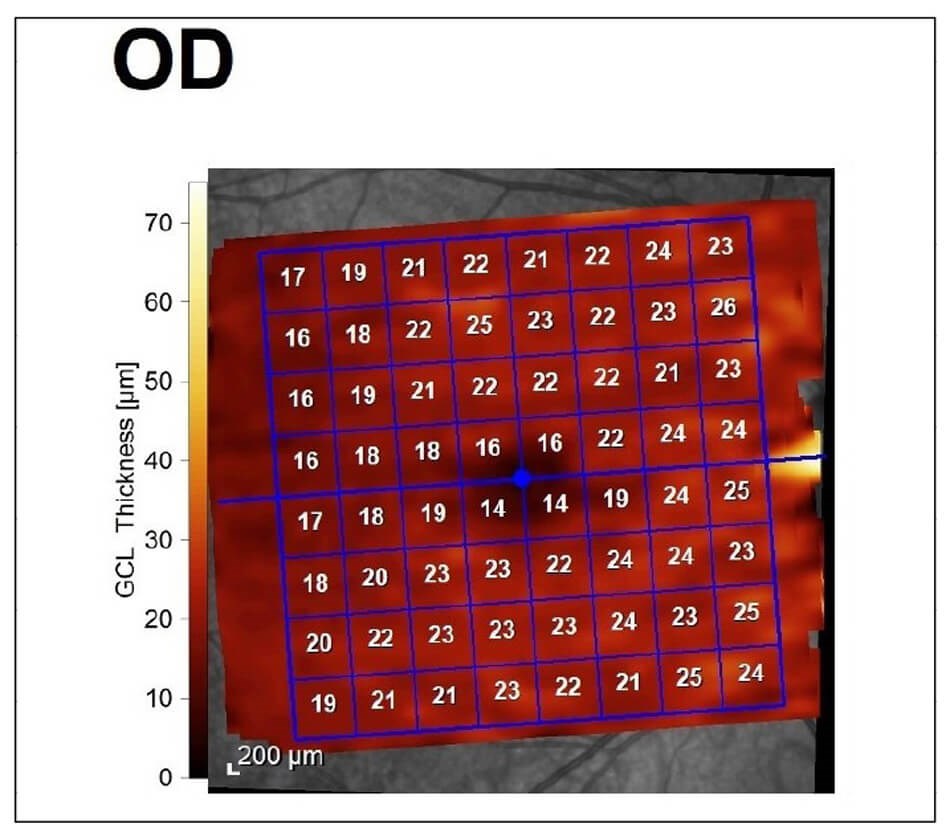

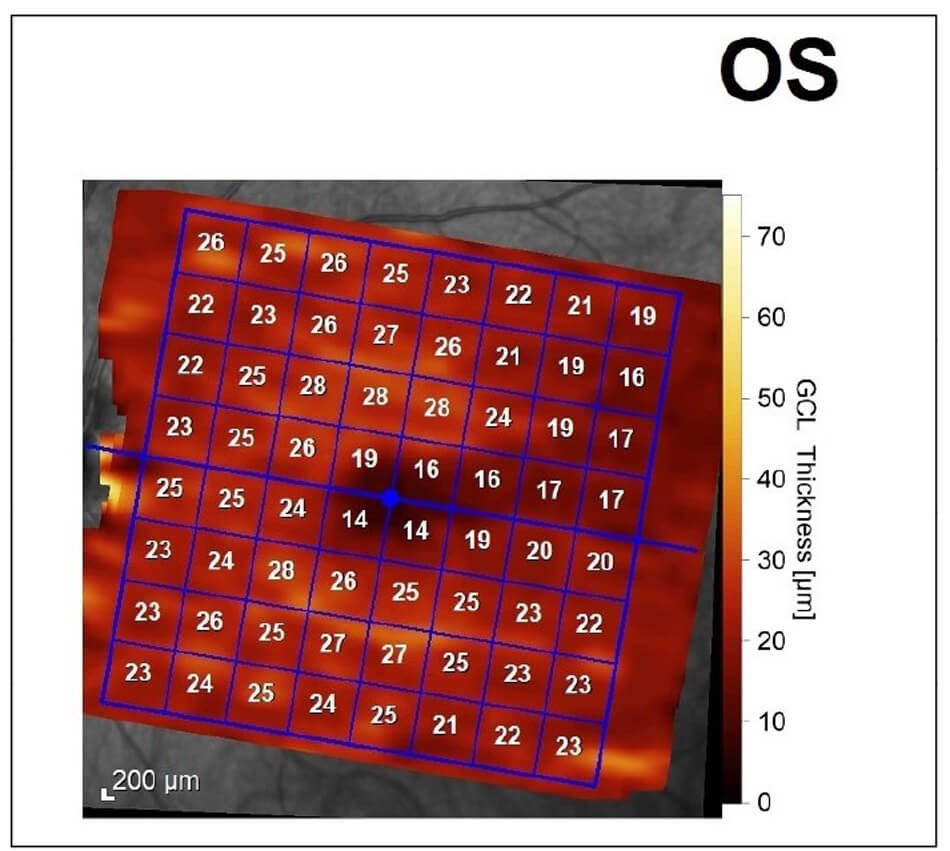

On examination, best-corrected Snellen visual acuity was 6/12 right eye and 6/9 left eye. There was no relative afferent pupillary defect. Ocular movements were full but there was a small amplitude high-frequency nystagmus. Colour vision was 1/17 on Ishihara plates in either eye. Anterior segments appeared healthy. On dilated fundoscopy, there was bilateral pigmentary maculopathy and optic nerve pallor (Figure 1). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealed bilateral diffuse retinal nerve fibre layer thinning and ganglion cell layer loss (Figure 2). Visual fields were surprisingly preserved with minimal peripheral visual loss.

Figure 2a: OCT revealed bilateral diffuse retinal nerve fibre layer thinning.

Figure 2b: Diffuse ganglion cell loss.

Figure 2c: Diffuse ganglion cell loss.

Investigations including B12 and folate levels, autoimmune screen, aquaporin 4 and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies were all normal. An MRI brain and orbits were requested which showed bilateral optic nerve atrophy involving both the orbital, canalicular and pre-chiasmatic segments of the nerves as well as atrophy of the optic chiasm. The images were compared to a previous MRI five years earlier, where atrophy was already evident but missed.

The patient was subsequently referred for genetic testing. A missense variant in the WFS1 gene homozygous state was found which was considered pathogenic. As a result, the patient was advised to consult an endocrinologist for hormonal screen which was negative and to have a hearing test which showed borderline sensorineural hearing impairment.

The diagnosis of Wolfram syndrome was made based on the existence of one major criterion, optic atrophy, and two minor criteria, sensorineural deafness and loss of function mutation in WFS1 gene. There were two further supporting features, those of insomnia and pigmentary maculopathy associated with the syndrome. Unfortunately, her parents and extended family live abroad, and we could not screen them. Further, the patient had no previous ophthalmic records available, apart from the MRI imaging, to be able to comment on progression of the optic neuropathy. The patient has been followed up for 24 months and there was no evidence of significant progression based on OCT imaging and visual fields.

Discussion

Wolfram syndrome has an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance but may rarely be due to an autosomal dominant mutation. Two different subtypes of Wolfram syndrome have been identified, WS1 and Wolfram syndrome 2 (WS2), each associated with a different disease gene, WFS1 and CISD2 respectively [2]. Wolfram syndrome 1, the more common of the two, codes for wolframin, a transmembrane protein found in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and mutation of it leads to accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER and therefore ER stress. Further, ER stress has been linked with dysregulation of intracytosolic calcium homeostasis, impairment of mitochondrial dynamics and inhibition of neuronal development. Highly metabolically active cells, like the retinal ganglion cells, are predominantly affected from the chronic ER stress resulting in apoptosis and loss of function.

Wolfram syndrome 1 is uncommon, with a reported prevalence of 1:500,000 and the highest prevalence, 1:68,000, is found in the Levant area due to greater rates of consanguinity [1]. Our patient is an Ashkenazi Jew with links to the Levant area but with no known consanguinity.

Although efforts have been made, it is still challenging to formulate correlations between genotype and phenotype, due to the high molecular complexity of WS1 with more than 200 mutations known, the absence of large patient cohorts and the variety of clinical characteristics [1]. Studies have shown that patients with absent wolframin production have more severe disease with earlier presentation than patients with residual wolframin expression [3]. Missense mutations, like our patient, and single amino acid insertions in both alleles result in milder degradation of wolframin with some residual function [3]. This may explain the favourable outcome of our patient so far.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is typically the first clinical feature of WS1 and differs from classical type I DM. In WS1, the diagnosis is earlier, autoantibodies are often absent, ketoacidosis is rare, and the doses of insulin required are lower and associated with frequent episodes of hypoglycaemia [3]. Even though DM is present in over 95% of patients with WFS1, recessive wolfram-like disease without DM, like our case, has been described [3].

The most common ocular manifestation is optic nerve atrophy presenting in the second decade of life with reduced visual acuity and colour vision [4]. Diabetic retinopathy is less commonly seen than in patients with type I or type II diabetes most likely due to less oxygen demand following loss of retinal tissue. Less common ocular features are that of pigmentary retinopathy and nystagmus, both of which were present in our patient.

There is currently no known treatment for the condition apart from supportive measures. The patients are advised to have regular hormonal level checks, hearing tests and ophthalmic reviews [1-4]. Experimental treatments focus on medications that reduce ER stress, regenerative therapy with pluripotent stem cells and gene therapy [1-4]. Unfortunately, life expectancy is shortened with approximately 65% of patients dying before 30 to 40 years due to respiratory failure or dysphagia [2].

Conclusion

Even though WS1 is a rare neurodegenerative disorder, it should be considered as differential diagnosis in patients with unexplained bilateral optic nerve atrophy. As in our case, not all patients of WS1 have the classical triad of diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus and optic nerve atrophy, and this often results in a delayed diagnosis.

References

1. Rigoli L, Bramanti P, Di Bella C, et al. Genetic and clinical aspects of Wolfram syndrome 1, a severe neurodegenerative disease. Pediatr Res 2018;83:921–9.

2. Pallota MT, Tascini G, Crispoldi R, et al. Wolfram syndrome, a rare neurodegenerative disease: from pathogenesis to future treatment perspectives. J Transl Med 2019;17(1):238.

3. Delvecchio M, Iacoviello M, Pantaleo A, et al. Clinical Spectrum Associated with Wolfram Syndrome Type 1 and Type 2: A Review on Genotype–Phenotype Correlations. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18(9):4796.

4. Urano F. Wolfram Syndrome: Diagnosis, Management, and Treatment. Curr Diab Rep 2016;16(1):6.

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.