An oculogyric crisis (OGC) is a dystonic movement disorder of the eyes which can last from seconds to hours. Although there is no published diagnostic criteria for OGC, typically the onset is acute, and it is characterised by conjugate upward deviation of the eyes with preserved consciousness [1]. Mimic presentations do exist which include paroxysmal tonic upgaze, ocular dyskinesias, ocular bobbing, ocular tics, seizures, and functional neurological disorders [2].

The pathophysiology of OGC remains unknown. It was first described in patients with encephalitis lethargica and post-encephalitic parkinsonism, however much more commonly, OGC can be attributed to medications, namely dopamine receptor blocking agents [2]. More rarely it can be associated with neurodegenerative disorders such as Rett’s syndrome or Kufor-Rakeb disease and it has been described in structural pathologies including midbrain infarcts, brainstem encephalitis and paraneoplastic syndromes.

Case

A 33-year-old Caucasian female presented to the emergency department with sudden onset involuntary left upgaze of both eyes which started whilst she was driving her car. Initially the eyes were fixed in the upper left position and the patient found the episode extremely uncomfortable. Her consciousness was preserved throughout, and she had no other subjective or objective neurological findings otherwise. After one hour the patient could briefly voluntarily bring both eyes back into central gaze position. A further one hour later the episode had resolved with no medical intervention.

She reports no other previous episode and no other recent ocular symptoms including no headache, diplopia, red eye, changes in vision nor eye pain. For the two weeks preceding she described a constant tingling sensation across her upper and lower distal limbs and had been feeling more tired than normal.

She had a past medical history of well controlled asthma and chronic back pain for which she had no recent change in medication. She had no history of seizures, tics nor functional neurological conditions. This patient had no history of alcohol excess or malabsorptive gastrointestinal illness.

Figure 1: Acute oculogyric crisis. Image used with patient consent.

On examination, she was conscious with sustained left conjugate upgaze of both eyes as shown in Figure 1. After the episode resolved, in both eyes she had 6/6 visual acuity with no diplopia on normal eye movements, normal fundus examination and normal pupillary reflexes. She had a normal neurological examination and normal vital observations.

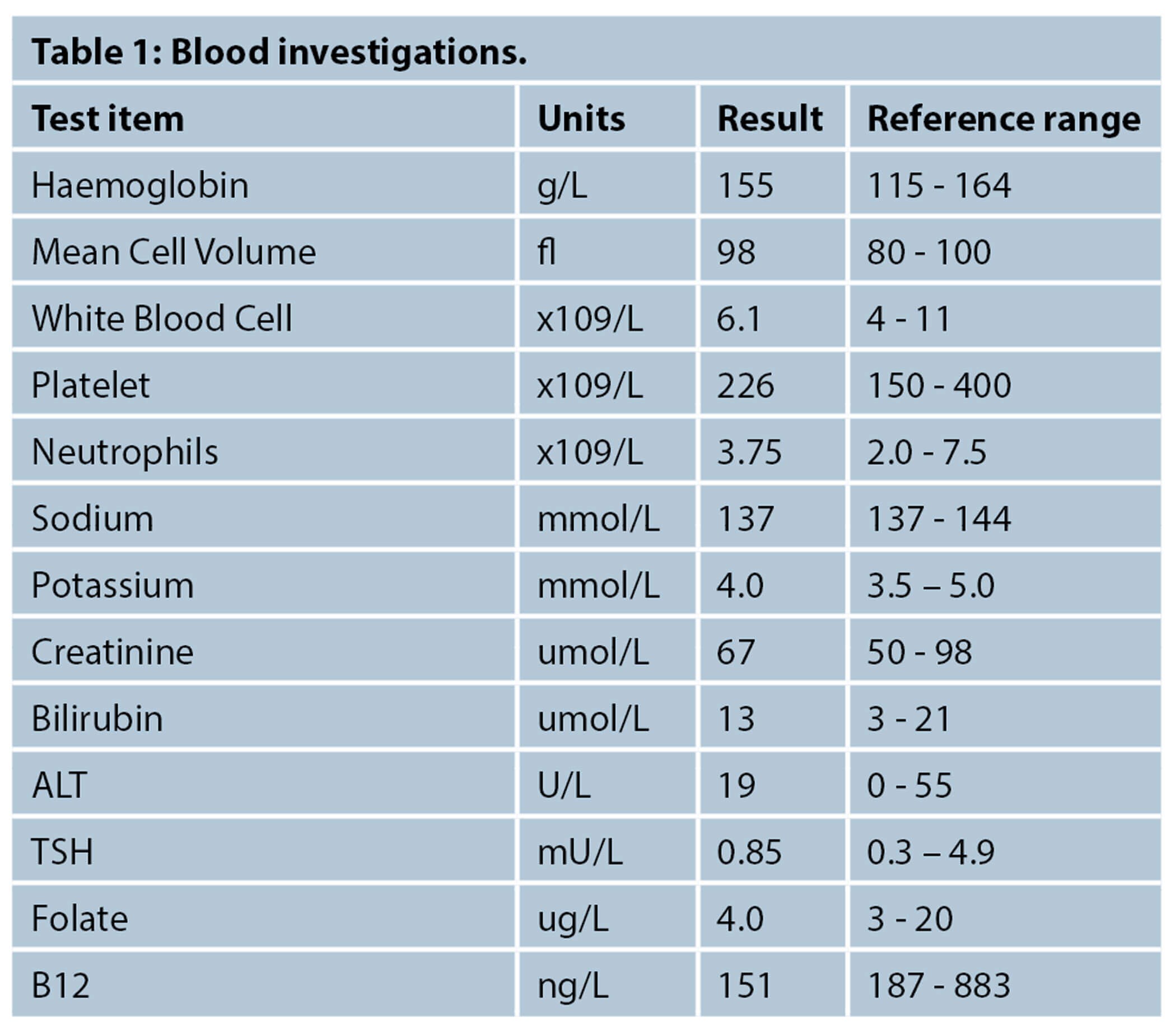

She was admitted under the Neurology team and underwent extensive investigations which returned normal results including a CT head, CT head angiogram and non-contrast MRI head. Her blood tests, included below, were essentially unremarkable other than a significant B12 deficiency 151ng/mL (200-883ng/L).

She was followed up several months after completing vitamin supplementation whereafter her sensory symptoms had resolved, and she reported no further dystonic movements.

Discussion

This patient presented with all of the clinical features of a genuine OGC without any obvious attributable trigger which presented a diagnostic interest for the medical team assessing this patient. Whilst the mimics of OGC, such as functional neurological disorder, remain a possibility, there was low diagnostic suspicion for her case. In the absence of attributable medications or structural disease, she was discharged with the diagnosis of an idiopathic oculogyric crisis.

Her case raises the question that the only noteworthy finding, significant B12 deficiency, was the cause for her sensory symptoms and possible association to the OGC. This case further demonstrates that whilst advanced imaging should be done in cases of unusual neurological presentations, basic investigations such as blood tests should not be dismissed.

B12 deficiency is relatively common, affecting approximately 3% of people between the age of 20-39 years old. It is most often caused by poor dietary intake, but can also be caused by malabsorptive problems or autoimmune diseases such as pernicious anaemia and Sjorgen syndrome [3]. The deficiency is confirmed by serum cobalamin blood testing, and whilst the clinically normal level can be controversial, it is thought that serum levels of less than 200pg/mL represents a significant deficiency [4].

B12 deficiency can present with a spectrum of haematological, gastrointestinal and neurological features. The neurological features of B12 deficiency in adults can occur at different serum levels of deficiency and are well documented. They typically include paraesthesia, fatigue, ataxia, and syncope. In advanced cases, cognitive impairment, sub-acute combined degeneration of the dorsal and lateral columns and optic atrophy are known presentations [5]. Involuntary movements are a rare but documented manifestation of B12 deficiency and can include parkinsonism, myoclonus and rarer still, dystonia [6]. There have been no published case reports of OGC directly associated with B12 deficiency, however there are published reports of ocular movement disorders attributed to the deficiency including blepharospasm and delayed saccades [7,8].

References

1. Mahal P, Suthar N, Nebhinani N. Spotlight on oculogyric crisis: a review. Indian J Psychol Med 2021;43(1):5-9.

2. Slow EJ, Lang AE. Oculogyric crises: a review of phenomenology, etiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Mov Disord 2017;32(2):193-202.

3. Shipton MJ, Thachil J. Vitamin B12 deficiency - a 21st century perspective. Clin Med (Lond) 2015;15(2):145-50.

4. Devalia V, Hamilton M, Molloy A. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders. Br J Haematology 2014;166(4):496-513.

5. Ammouri W, Harmouche H, Khibri H, et al. Neurological manifestations of cobalamin deficiency. Open Access J Neurol Neurosurg 2019;12(2):555834.

6. de Souza A, Moloi MW. Involuntary movements due to vitamin B12 deficiency. Neurol Res 2014;36(12):1121-8.

7. Edvardsson B, Persson S. Blepharospasm and vitamin B12 deficiency. Neurol India 2010;58(2):320-1.

8. Sharrief AZ, Raffel J, Zee DS. Vitamin B12 deficiency with bilateral globus pallidus abnormalities. Arch Neurol 2012;69(6):769-72.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME