Hypertensive anterior uveitis can present a diagnostic challenge to clinicians working in emergency eye departments. While prompt initial control of intraocular pressure (IOP) and inflammation is essential, elucidating the underlying aetiology is critical for long-term visual outcomes.

When there is chronic or recurrent hypertensive uveitis, and especially where iris stromal atrophic changes are present, cytomegalovirus (CMV) should be high on the differential. Symptoms may be insidious in the early stages, and classic features such as posterior synechiae, keratic precipitates and photophobia may be strikingly absent [1]. Given these limitations, early diagnostic anterior chamber (AC) paracentesis and multi-specialty involvement is paramount to allow targeted treatment and prevent irreversible glaucomatous optic neuropathy.

Case report

A 67-year-old male presented to our emergency department four years ago with unexplained ‘misting’ of vision in his right eye, lasting hours at a time and sometimes associated with dilation of the pupil. He described right-eye grittiness, foreign body sensation and intermittent redness with no photophobia. Initial slit lamp examination was unremarkable; IOPs were normal with wide-open angles and no inflammation.

On subsequent review, he was incidentally found to have raised IOP in his right eye with optic disc changes suspicious of glaucoma. He was commenced on IOP-lowering drops (timolol 0.5% and dorzolamide 2%) and monitored in the glaucoma clinic.

Three years after the initial symptoms began, he presented again with right eye blurry vision, now associated with orbital pain, and his IOP measured 58mmHg with mild anterior chamber inflammation. He was treated with intravenous acetazolamide 500mg, topical IOP-lowering medications and topical steroids (dexamethasone 0.1%). On follow-up, his IOP improved to 20mmHg and inflammation settled, but his optic disc changes had progressed significantly with a cup-to-disc ratio of 0.85 in the right eye and associated glaucomatous visual field changes. Screening uveitis bloods and chest X-ray were negative. He was reviewed again by the glaucoma team who began to consider a glaucoma drainage tube to control IOP and limit progression of optic neuropathy.

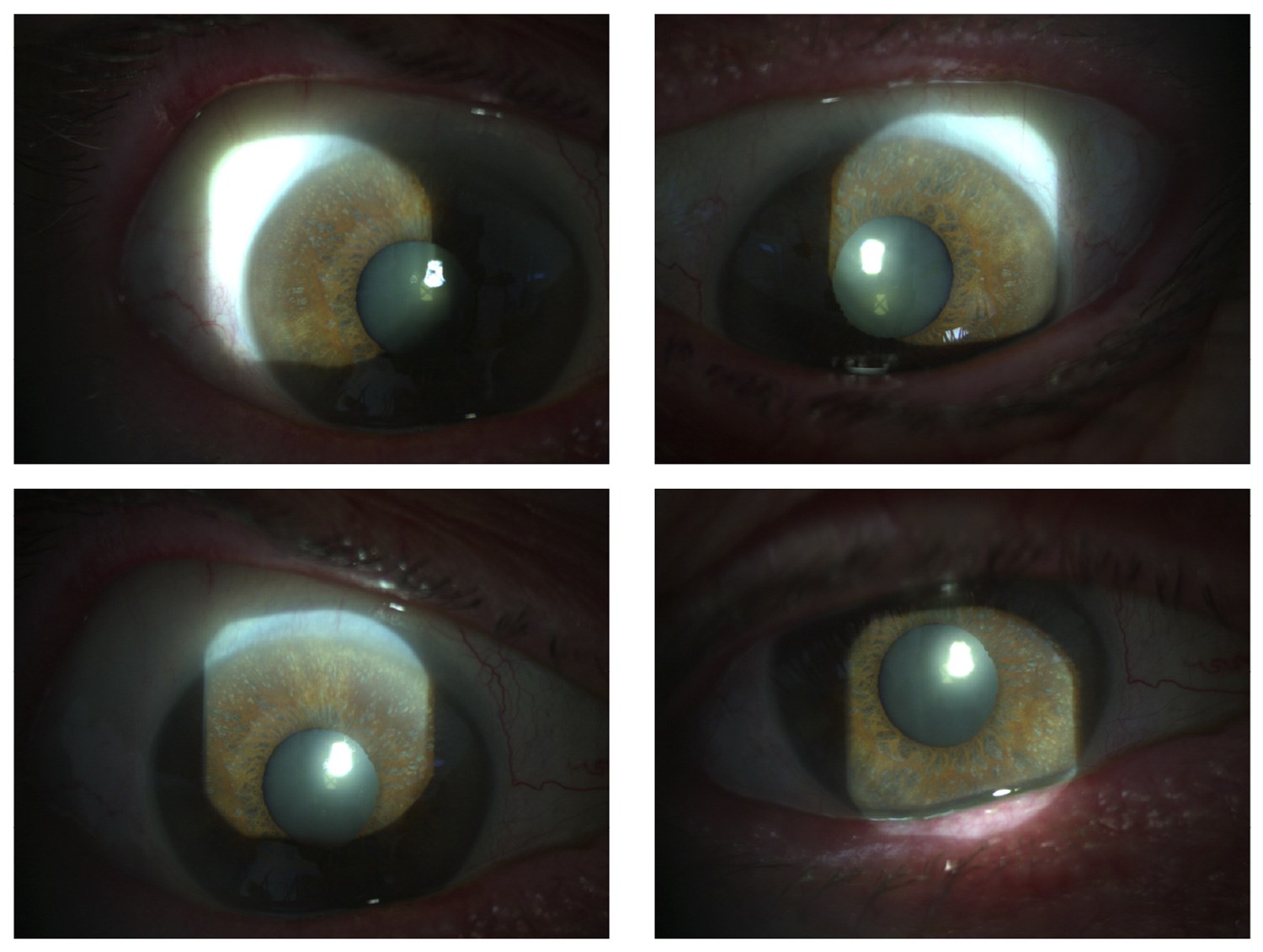

Figure 1. Right eye slit-lamp photograph. Moth-eaten sectoral iris atrophy without transillumination in patient’s right eye following CMV hypertensive anterior uveitis.

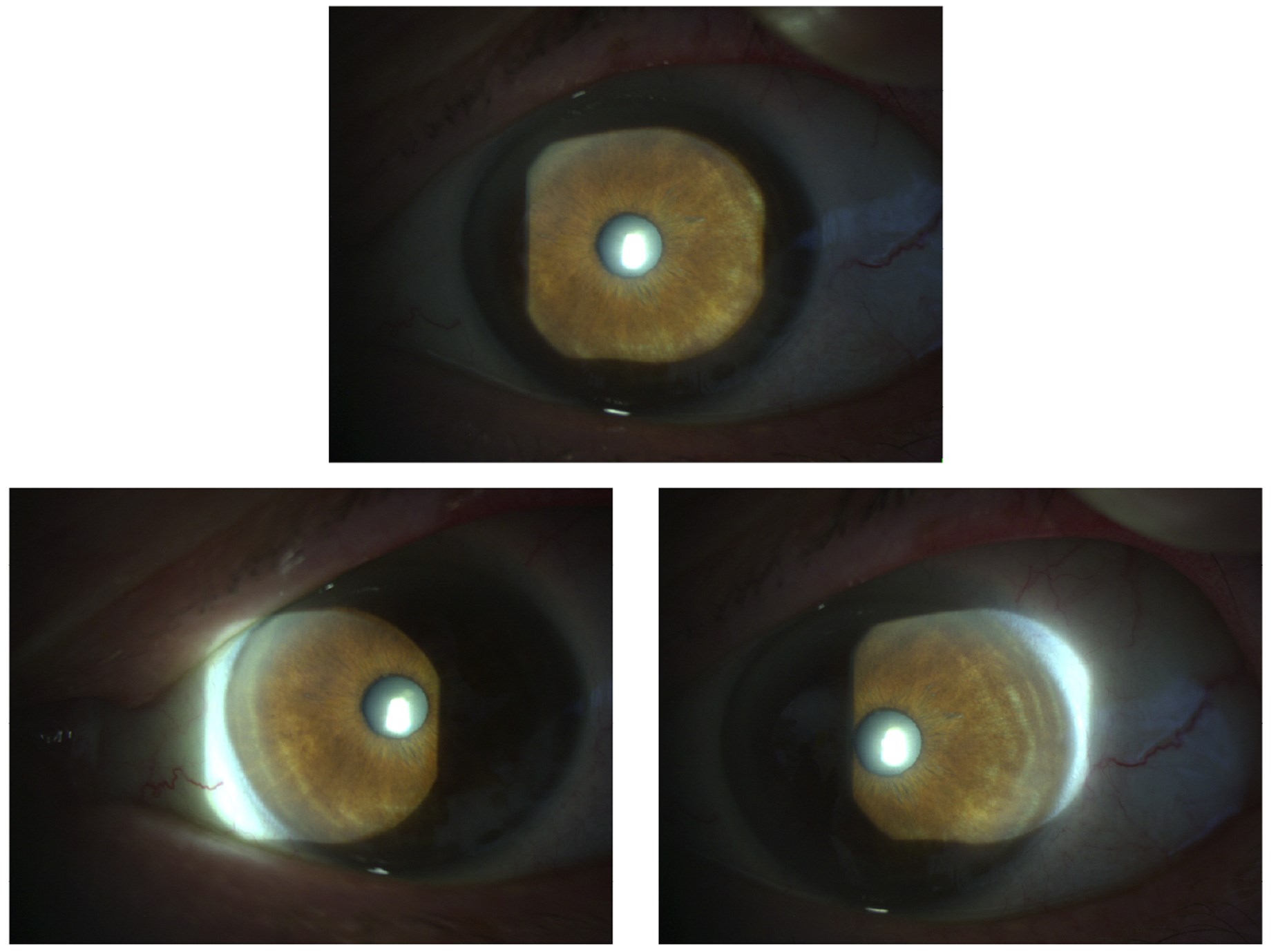

Figure 2. Left eye for comparison: healthy iris stromal appearances.

He was referred to a uveitis specialist who noted an atrophic, moth-eaten appearance of the iris (Figure 1) and suspected CMV as an underlying aetiology. Over 48 hours after the onset of a subsequent flare, an AC paracentesis was performed and PCR analysis of the aqueous sample returned positive for CMV DNA. The patient was started on oral valganciclovir 900mg twice daily for two weeks then 450mg twice daily for two months. After treatment initiation the patient reported a subjective improvement in his vision. Thus far on subsequent visits his intraocular pressures have been within normal range with no further episodes of blurry vision, although he remains under close observation.

Discussion

Cytomegalovirus hypertensive uveitis is a well-recognised yet under-appreciated cause of recurrent or chronic hypertensive uveitis, with several case reports described in the literature [2,3]. We present a case where uveitis remained undiagnosed for several years due to insidious symptoms and subtle clinical signs, while glaucomatous optic neuropathy was slowly progressing. Only after episodes of full-blown hypertensive uveitis and characteristic atrophic ‘moth-eaten’ iris changes were noted in the uveitis clinic was an AC paracentesis prompted and performed. Notably even though the tap was done over 48 hours after presentation, the aqueous sample yielded a positive PCR for CMV. This underscores that even a delayed AC tap after the initiation of steroid drops and IOP-lowering treatment for anterior uveitis can be diagnostically useful.

A collaborative approach with early multi-specialty input integrating uveitis and glaucoma expertise is critical for good long-term visual outcomes [4,5]. While our patient has developed a glaucomatous optic neuropathy, his central vision remains excellent, and we hope that continued remission after initiating antiviral treatment will protect against damaging IOP spikes. The aim would be to spare him the need for a drainage tube and future courses of topical steroids and IOP lowering drops, reducing morbidity, side effects and treatment burden, and ultimately altering the course of his disease.

Conclusion

This case highlights that in hypertensive unilateral uveitis with characteristic iris changes, CMV should be strongly suspected. Early (or even delayed) AC paracentesis for PCR confirmation is invaluable in guiding targeted treatment. Moreover, a multidisciplinary approach is critical to preserving vision and limiting glaucomatous progression.

References

1. Choi JA, Kim KS, Jung Y, et al. Cytomegalovirus as a cause of hypertensive anterior uveitis in immunocompetent patients. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect 2016;6(1):32.

2. Romano J, Godinho G, Chaves J, et al. Cytomegalovirus-Induced Hypertensive Anterior Uveitis: Diagnostic Challenge in an Immunocompetent Patient. Cureus 2024;16(1):e52826.

3. Xi L, Zhang L, Fei W. Cytomegalovirus-related uncontrolled glaucoma in an immunocompetent patient: a case report and systematic review. BMC Ophthalmol 2018;18(1):259.

4. Zhang J, Kamoi K, Zong Y, et al. Cytomegalovirus Anterior Uveitis: Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Immunological Mechanisms. Viruses 2023;15(1):185.

5. Boonhaijaroen T, Choopong P, Tungsattayathitthan U, et al. Treatment outcomes in cytomegalovirus anterior uveitis. Sci Rep 2024;14(1):15210.

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.