Corneal hysteresis (CH) is gaining recognition as a valuable parameter in the management of glaucoma. Corneal hysteresis is defined as the difference between the inward and outward pressure responses of the cornea during deformation. This measurement reflects the viscoelastic properties of the cornea, which include its elasticity (ability to regain shape) and viscosity (ability to dissipate energy).

Corneal hysteresis is therefore a measure of the cornea’s ability to absorb and dissipate energy when subjected to a force, such as during an intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement.

Corneal hysteresis values are expressed in millimetres of mercury (mmHg). They are repeatable and exhibit individual variation. Average CH values in non-pathological eyes typically range from 10.2–10.7mmHg.

A higher CH value indicates a more elastic and resilient cornea, while a lower value suggests a stiffer or less deformable cornea. Corneal hysteresis is clinically significant and associated with various eye conditions, including glaucoma.

Biomechanics of cornea

The biomechanics of the cornea focus on its structural and mechanical properties, which are crucial for maintaining its shape, transparency, and refractive function. Primarily governed by the stroma, which provides tensile strength through its organised collagen matrix, the cornea exhibits both elastic and viscoelastic behaviour, enabling it to withstand and recover from mechanical stress. Factors such as IOP, hydration, age, and disease influence its biomechanical integrity. Advanced measurement techniques, like CH and elastography, aid in assessing these properties. Understanding corneal biomechanics is vital for managing conditions like keratoconus, optimising refractive surgeries, and designing treatments such as collagen cross-linking to enhance corneal strength and stability.

Corneal hysteresis measurement devices

Currently, there are three devices on the market used to measure CH [1].

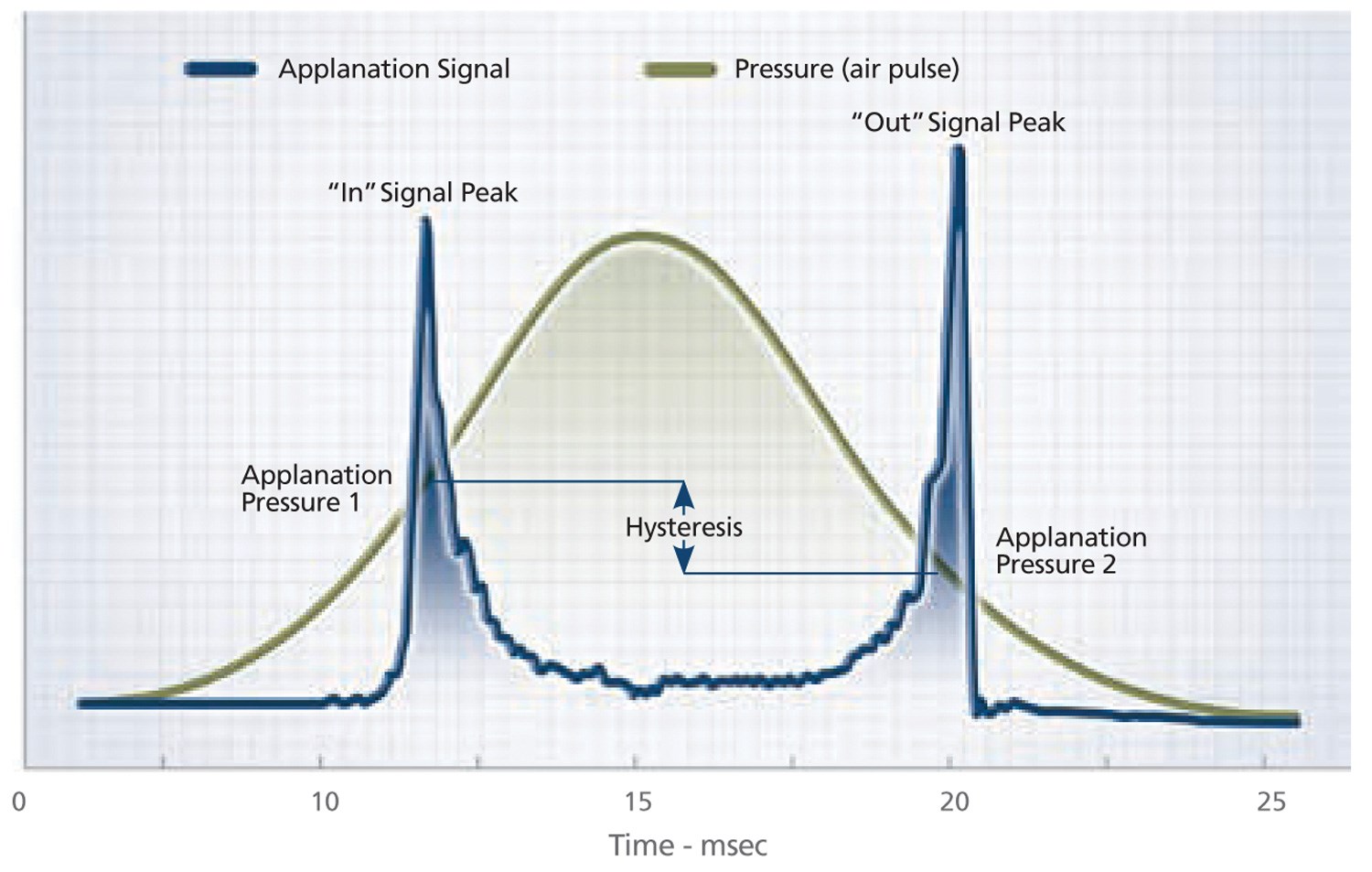

Figure 1: Ocular response analyser pressure profile.

1. Ocular response analyser (ORA; Reichert, Inc)

The ORA uses a quick jet of air to indent the cornea and an electro-optical system is used to measure the applanation pressure, once when the cornea is displaced inward, and again when it is displaced outward. The cornea has viscoelastic properties and therefore it resists inward movement caused by the air pulse and reverts to its primary position due to its elastic nature. There is a delay between these applanation events. The first inward applanation pressure is termed pressure 1 (P1) and the second or outward pressure event is classified as pressure 2 (P2) (Figure 1).

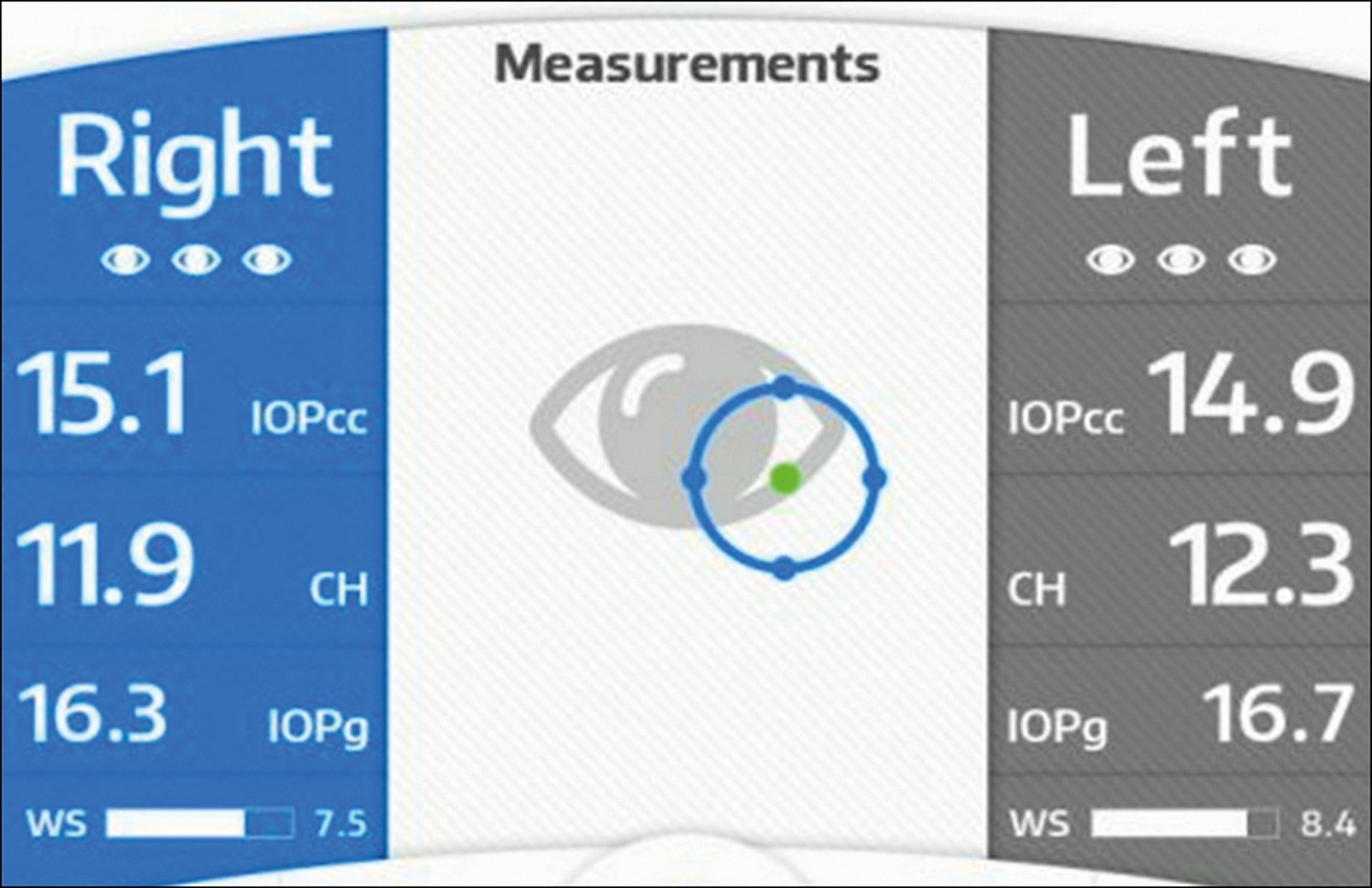

Figure 2: Ocular response analyser measurements.

Measurements produced by the ORA (Figure 2)

- IOPg: ‘The Goldmann-correlated IOP’ is analogous to Goldmann tonometry and is the average of applanation P1 and P2.

- IOPcc: ‘Corneal-compensated IOP’ is a pressure measurement that utilises CH to provide a pressure value that is more reproducible and less influenced by intrinsic corneal properties, such as central corneal thickness (CCT).

- CH: ‘Corneal hysteresis’ is the difference between P1 and P2.

- CRF: ‘Corneal resistance factor’ is an algorithmic measure of the cornea’s overall resistance. It is derived from the formula P1-kP2, where ‘k’ is the constant determined from an empirical analysis of the relationship between both P1 and P2 and CCT.

- WS: ‘Waveform signal’ is for reliability.

2. Corneal Visualization Scheimpflug Technology (Corvis ST; Oculus)

Similar to the ORA, the Corvis ST utilises an air pulse, but a high-speed Scheimpflug camera is used to calculate corneal movement. The camera can record up to 4300 images per second, creating a highly detailed visualisation of the cornea’s movement. The device calculates a biomechanically corrected intraocular pressure (bIOP), similar in concept to the IOPcc from the ORA, but derived through different means. Unlike the ORA, the Corvis ST does not directly measure CH. However, the calculated bIOP incorporates CH effects, making it a functional alternative. Parameters from the Corvis ST are not directly comparable to those from the ORA, as the two devices use distinct measurement techniques and algorithms.

3. Brillouin microscopy (BM)

This is an emerging method offers a non-contact three-dimensional evaluation of corneal biomechanics. It relies on the light scattering and is independent of the IOP. However, its application in evaluating corneal biomechanics in glaucoma patients remains unexplored.

Corneal-compensated intraocular pressure

Central corneal thickness has long been considered a risk factor for glaucoma. However, CCT is a geometric measurement and does not fully capture the biomechanical behaviour of the cornea [2]. Central corneal thickness significantly affects IOP readings obtained via Goldmann applanation tonometry (GAT). Intraocular pressure is underestimated in thin corneas and overestimated in thick corneas.

The connection between CCT and GAT IOP can make it difficult to evaluate CCT as an independent risk factor for glaucoma. To accurately assess its role, IOP measurements that are not influenced by CCT would be needed. The IOPcc, measured using the ORA, has been proposed as an alternative metric that accounts for corneal properties and minimises the influence of CCT. Unlike GAT IOP, IOPcc shows little to no correlation with CCT, providing a more reliable estimate of true IOP.

Research by Susanna, et al. demonstrated that IOPcc correlates better with glaucoma progression, particularly with rates of visual field loss, compared to other tonometers [3]:

- ORA IOPcc: Strongest correlation with visual field loss progression (R² = 24.5%)

- GAT: Moderate correlation (R² = 11.1%)

- iCare Tonometer: Weak correlation (R² = 5.8%).

Central corneal thickness’ role as a glaucoma risk factor is important but limited by its indirect influence on IOP measurement. Corneal-compensated IOP, being less affected by corneal properties, represents a more reliable tool for assessing glaucoma risk and progression.

Corneal hysteresis as a risk factor for glaucoma

A prospective cohort study by Susanna, et al. followed 287 eyes of 199 glaucoma suspects with normal baseline visual fields for an average of 3.9 years to assess CH as a risk factor for glaucoma [4]. During follow-up, 19% of eyes developed glaucomatous visual field defects. Baseline CH was significantly lower in eyes that developed glaucoma (9.5mmHg) compared to those that did not (10.2mmHg; p=0.012). Each 1mmHg lower CH was associated with a 21% increased risk of glaucoma (p=0.013), and this relationship remained significant in multivariable analysis (hazard ratio = 1.20; p=0.040). These findings highlight CH as an independent risk factor for glaucoma development.

Zhang B, et al. conducted a cross-sectional study which analysed CH data from 93,345 participants in the UK Biobank cohort, aged 40–69 years, to evaluate its distribution, associated factors, and clinical relevance [5]. The mean CH was 10.6mmHg, with lower CH values associated with male sex, older age, black ethnicity, self-reported glaucoma, and lower diastolic blood pressure. Higher CH was linked to smoking, hyperopia, diabetes, systemic lupus erythematosus, and higher deprivation scores. A significant association between lower CH (<10.1mmHg) and self-reported glaucoma was observed, suggesting that CH may serve as a valuable biomarker for glaucoma detection, particularly in those with low CH values. The findings give further support to a threshold of <10mmHg, which has been used as a rule of thumb for low CH when estimating risk of glaucoma.

Difference in corneal hysteresis between normal and glaucoma patients

In a cross-sectional study of Chinese patients in Singapore, involving 443 participants Narayanaswamy, et al. compared CH and IOP in primary angle-closure glaucoma (PACG), primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), and normal eyes [6]. Corneal hysteresis was significantly lower in PACG (9.1mmHg) and POAG (9.5mmHg) compared to normal eyes (10.4mmHg). After adjusting for age, sex, and IOP measured by GAT, the lower CH remained significant in PACG compared to controls (9.4 vs 10.1mmHg; p=0.006).

In a study by Pillunat, et al. from Dresden, Germany, normal tension glaucoma (NTG) patients were defined as open-angle glaucoma patients with a history of untreated IOP ≤21mmHg, and these patients were compared with healthy controls [7]. Corneal hysteresis adjusted for age, axial length, CCT, and IOP was significantly lower in NTG patients (8.99 ±1.40mmHg; n=38 eyes) than in controls (9.86 ±1.42mmHg; n=44 eyes; p=0.005). There was no difference in adjusted CH between POAG and NTG patients (p=0.978). However, both POAG and NTG patients were currently receiving medical treatment for their glaucoma, leaving open the possibility that topical medications may have altered ocular biomechanical properties.

Corneal hysteresis as a risk factor for progression

The first link between CH and visual field progression was identified by Congdon, et al. in 2006 [8]. This observational study included 230 participants, of whom 85% had primary POAG and 15% were glaucoma suspects. The findings showed that lower CH was significantly linked to greater visual field progression, an association not observed with central CCT [9].

Susanna, et al. conducted a prospective observational study involving 199 patients suspected of having glaucoma, with a mean follow-up period of 3.9 years [10]. Glaucoma progression was defined as a Glaucoma Hemifield Test result outside normal limits or a Pattern Standard Deviation of <5% on three consecutive automated perimetry tests. Among the 54 eyes that developed repeatable visual field defects during follow-up, CH values were significantly lower compared to those whose visual fields remained stable. The study concluded that lower CH values were associated with a higher risk of developing glaucomatous visual field defects over time.

Medeiros, et al. investigated the relationship between CH and the rate of visual field index loss over time in 68 patients with diagnosed glaucoma (114 eyes), followed for an average of four years [11]. The study found that CH had a stronger association with glaucoma progression than IOP or CCT. Specifically, each 1mmHg decrease in CH was linked to a 0.25%/year-faster rate of visual field progression (p<0.001).

Zhang, et al. expanded the analysis beyond subjective visual field progression by investigating the relationship between CH and retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL) thinning [12]. This prospective study followed 186 eyes of 133 patients over an average of 3.8 years, with a median of nine visits. Retinal nerve fibre layer measurements were obtained using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography, and adjustments were made for potential confounding factors. The study found that lower CH was significantly associated with faster RNFL thinning, with each 1mmHg decrease in CH linked to a 0.13μm/year faster rate of RNFL decline (p=0.011).

Conclusions

Corneal hysteresis is a novel clinical parameter that reflects the ocular tissue’s response to transient compression and release, as measured by an air puff tonometer. While its interpretation can be complex due to the influence of various factors, CH provides valuable additional data. This information enhances the clinical assessment of glaucoma suspects and patients, offering insights into disease risk and progression that complement traditional diagnostic tools.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

-

Surrogate marker: Corneal hysteresis may reflect the biomechanical properties of deeper eye tissues, such as the lamina cribrosa and peripapillary sclera, which are linked to glaucoma risk.

-

Risk factor: Lower corneal hysteresis is a predictor of visual field loss in patients suspected of having glaucoma.

-

Progression: In glaucoma patients, reduced corneal hysteresis is associated with a higher risk of disease progression and faster visual field decline.

-

IOPcc advantage: Corneal compensated intraocular pressure, which minimises the influence of corneal artifacts, demonstrates a stronger correlation with glaucoma progression rates than IOP measured using Goldmann tonometry.

-

Clinical use: Measuring corneal hysteresis is recommended for all patients at risk for glaucoma and those already diagnosed.

References

1. Elhusseiny AM, Scarcelli G, Saeedi OJ. Corneal Biomechanical Measures for Glaucoma: A Clinical Approach. Bioengineering (Basel) 2023;10(10):1108.

2. Jammal AA, Medeiros FA. Corneal hysteresis: ready for prime time? Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2022;33(3):243–9.

3. Susanna CN, Ogata NG, Daga FB, et al. Association between Rates of Visual Field Progression and Intraocular Pressure Measurements Obtained by Different Tonometers. Ophthalmology 2019;126:49–54.

4. Susanna CN, Diniz-Filho A, Daga FB, et al. A Prospective Longitudinal Study to Investigate Corneal Hysteresis as a Risk Factor for Predicting Development of Glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2018;187:148–52.

5. Zhang B, Shweikh Y, Khawaja AP, et al. Associations with Corneal Hysteresis in a Population Cohort: Results from 96 010 UK Biobank Participants. Ophthalmology 2019;126:1500–10.

6. Narayanaswamy A, Su DH, Baskaran M, et al. Comparison of ocular response analyzer parameters in Chinese subjects with primary angle-closure and primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2011;129(4):429–34.

7. Pillunat KR, Hermann C, Spoerl E, Pillunat LE. Analyzing biomechanical parameters of the cornea with glaucoma severity in open-angle glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2016;254:1345–51.

8. Congdon NG, Broman AT, Bandeen-Roche K, et al. Central corneal thickness and corneal hysteresis associated with glaucoma damage. Am J Ophthalmol 2006;141:868–75.

9. Murtagh P, O’Brien CJ. Corneal Hysteresis, Intraocular Pressure, and Progression of Glaucoma: Time for a “Hyst-Oric” Change in Clinical Practice? Clin Med 2022;11(10):2895.

10. Susanna CN, Diniz-Filho A, Daga FB, et al. A Prospective Longitudinal Study to Investigate Corneal Hysteresis as a Risk Factor for Predicting Development of Glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;187:148–52.

11. Medeiros FA, Meira-Freitas D, Lisboa R, et al. Corneal hysteresis as a risk factor for glaucoma progression: A prospective longitudinal study. Ophthalmology 2013;120:1533–40.

12. Zhang C, Tatham AJ, Abe RY, et al. Corneal hysteresis and progressive retinal nerve fiber layer loss in glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2016;166:29–36.

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.