Historically, in NHS Grampian, ophthalmology and optometry worked separately, with even the process of optometry referral to hospital occurring only at the behest of the patient’s general practitioner (GP). Criteria for referral were not discussed and feedback after referral was rare. Unsurprisingly, optometry referrals were often thought by ophthalmology to be of poor quality, leading to little faith in the ability of optometry to manage any aspect of eye care.

Scotland’s 2006 General Ophthalmic Services Contract

In 2005, Optometry Scotland negotiated a new General Ophthalmic Services (GOS) Contract with the Scottish Government [1]. Optometry Scotland wished to make optometry the first port of call for all eye problems. They negotiated a new contract placing the emphasis on the universal provision of a free comprehensive clinical examination, rather than free refraction for a minority.

Community optometry services were envisaged on two levels. Level 1 services would be provided by all optometrists and would be funded centrally by the Scottish Government. Level 2 services would be provided by optometrists with additional skills, such as glaucoma refinement, or specialist medical contact lens fitting, and were to be funded locally.

To equip practices to a similar standard to ophthalmology, practice grants were provided for contact tonometry, threshold visual field perimetry, binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy lenses and a digital fundus camera.

All optometrists who wished to work under the new contract, had to undertake competency training. Some had to undergo retraining, and some chose not to undertake NHS work.

The new contract was implemented on 1 April 2006.

2007 eye care redesign

Simultaneously, between 2005 and 2007, the Scottish Government funded a national redesign initiative to reduce cataract waiting times and improve the delivery of eye care in general [2].

At that time, local access to eye care was haphazard, with patients randomly presenting to emergency medicine, general practice, pharmacy and optometry, or simply walking in to the eye clinic at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary.

A 2006 six week audit of ‘walk-ins’ to the eye clinic at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary showed that less than 10% of patients required the special skills of an ophthalmologist and that the majority of these were referred by optometry. Fifty percent of patients seen had no abnormality detected. Patient’s who self-referred had less than a 1% chance of actually needing an emergency appointment.

The scale of unplanned activity was considerable. In 2006, 6000 patients were seen in eye casualty, generating an additional 3000 return visits. This unscheduled activity exceeded the planned activity for similar specialties such as dermatology, gynaecology and otolaryngology. Ophthalmology’s capacity was stretched to the limits, with standing only room at the clinic and frustrated patients and doctors alike. Patient complaints about the eye service were numerous, usually about the length of time waiting at the clinic, rather than the care provided. The problem was brought to a crisis by changes in the length of general practice training, leading to two trainee posts being removed from ophthalmology for use elsewhere.

Something had to change. The current system was not working. Hospital capacity was reducing, yet patient demand for urgent eye care remained unabated. A glimmer of hope was the new GOS contract. If community optometry acted as a gatekeeper, even just to prevent patients with normal findings being seen in hospital, this might release enough capacity for those who did need to be seen.

Under the governance of the redesign programme, a decision was made to create an alliance of all affected parties, including patients, in the form of an Eye Health Network. The success, or otherwise, of the network would be determined by ophthalmology and optometry’s willingness to put aside professional differences and work together in partnership.

The Eye Health Network

The Eye Health Network commenced in 2007. The network is all encompassing, involving a patient panel, community optometry, ophthalmology, general practice, community pharmacy, emergency medicine and NHS 24. At its core are 58 optometric practices supported by a clinical decision unit (CDU) which can book directly into a daily ophthalmology urgent referral clinic (URC).

The Eye Health Network is a level 1 service with an additional optional Locally Enhanced Service contract. The Eye Health Network has formal clinical protocols for common presentations, ensuring a consistent standard of care. Optometrists have 24 hour access to advice – the CDU during normal working hours and on-call ophthalmology at other times.

Roles and responsibilities

Network roles and responsibilities are clearly defined. Optometry is promoted as the main provider of primary eye care and the best source of clinical information and guidance as to whether patients require referral to ophthalmology.

The key principle is that each optometrist works within the scope of their individual competence and seeks advice, or refers onwards, when their individual threshold of competence is reached.

Patient pathway

A clear patient pathway for acute ophthalmic presentations now exists and has been circulated to all primary care practitioners (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Patient pathway for acute ophthalmic presentations. Grampian Medical Emergency Department (GMED).

Clinical pathways

Support for optometry is in two forms. The 12 most common symptomatic eye presentations were identified and patient pathways drawn up according to best practice. As it is impossible to cover all options, anything requiring support outwith these pathways is dealt with by contacting the CDU and asking for advice.

Locally Enhanced Services / Clinical Accord

To increase the number of patients who can be treated by optometry a voluntary Locally Enhanced Service (LES) Contract was introduced in 2010 for dendritic herpes simplex keratitis, marginal keratitis, acute anterior uveitis and corneal foreign body removal. Additional educational sessions, including a skills assessment session on removing ocular foreign bodies were undertaken.

A Clinical Accord was agreed with General Medical Practice. GPs agreed to prescribe prescription-only medicines (prednisolone 1% eye drops, acyclovir 3% eye ointment) when the protocols were adhered to.

NHS Grampian provides sterile needles, Alger brush devices and tips for those who complete foreign body removal training.

These level 2 activities follow a rigid protocol and if there is doubt, clinical advice is always to be obtained. The acute anterior uveitis protocol requires all patients to be referred, timing dependent on severity, but initial treatment and follow-up is provided by optometry, supported by general practice.

Clinical decision unit

The CDU is a point of contact accessible by optometry and general practice only. Situated within the ophthalmology department, this service is nurse led, but with ready access to a doctor. It is the link between primary and secondary care issuing advice and receiving all referrals. Patients may be booked routinely to the most appropriate clinic or urgently into a daily, afternoon urgent referral clinic. The CDU allows two way communications across the primary / secondary care boundary and is an essential part of the Eye Health Network system.

Urgent referrals

Optometry practices agree to follow a code of practice to ensure patients are seen in appropriate time within the network. When a patient presents with an eye health problem, either by self-presenting or referred by another health professional, it becomes the responsibility of the practice consulted to have the patient seen and in reasonable time.

This can be by:

- fitting them in to the practice schedule

- contacting another practice and having them accept the patient

- as a last resort, telephoning the clinical decision unit helpline and asking the hospital clinic to see the patient.

The pathway for children differs in that if the practice cannot see the patient in an appropriate timescale, the CDU is contacted and a hospital URC appointment issued. The URC is a consultant-supervised clinic running five days per week for patients requiring urgent ophthalmology assessment and care.

Routine advice

All optometry practices have their own NHSmail account. Where the optometrist decides that urgent referral is not indicated, but still wishes advice on how best to manage the patient in the community, they can email the CDU. An automatic reply reminds the sender that emails are only replied to weekly.

Routine referral

Where the optometrist decides that a routine referral is appropriate, they can refer the patient directly to the CDU using a bespoke electronic referral system. This enables images, visual fields and other documents to be attached in addition to the referral. Where appointment is not required, a reply with advice can be sent.

Training

Training is given to each and every optometric member of the Eye Health Network prior to participation within the network. This is in two areas:

- a rules and responsibilities lecture

- a session working with an ophthalmologist at the urgent referral clinic or a Teach and Treat clinic

The intention of this training is not to up-skill optometrists in primary care ophthalmology, but to impart to all their role within the network and their responsibilities, to introduce them to their ophthalmology colleagues and to make them aware of network workings.

Additional evening educational meetings are held three times a year. Those registered for the Locally Enhanced Service Contract are required to attend two out of three meetings. Attendance is good; meetings are held in Aberdeen with video links to Elgin and Shetland. The content is based on issues arising within the network, ophthalmology feedback from vetting of electronic referrals and the requirements for continuing education on the LES conditions.

A Teach and Treat clinic within ophthalmology is funded by NHS Education Scotland. This allows optometrists to book sessions for ‘hands-on’ assessment of patients in a well equipped facility, supervised by a senior ophthalmologist. When Network monitoring identifies optometrists lacking skills in a specific area they are required to attend a clinic where education and assessment can be carried out.

Management

An Eye Health Network board oversees the running of the network. Key personnel are a lead clinician (ophthalmologist), a lead optometrist for the Eye Health Network, a member for clinical governance, a general practitioner, a pharmacist advisor and a patient representative. In addition, representatives from all other involved parts of the service are present.

Audit

Audit is an integral part of the service. Data have been collected and analysed in a series of audits from inception. Initial audits provided reassurance that patients were being seen in the community and that patients were not simply redirecting themselves to emergency medicine. Later audits confirmed the diagnostic accuracy of community optometry referrals to the urgent referral clinic, with agreement in 90% of cases. Further audits have led to the development of key performance indicators and a rolling programme of six monthly audits of symptomatic presentation is planned.

Impact on clinical care

Ophthalmology

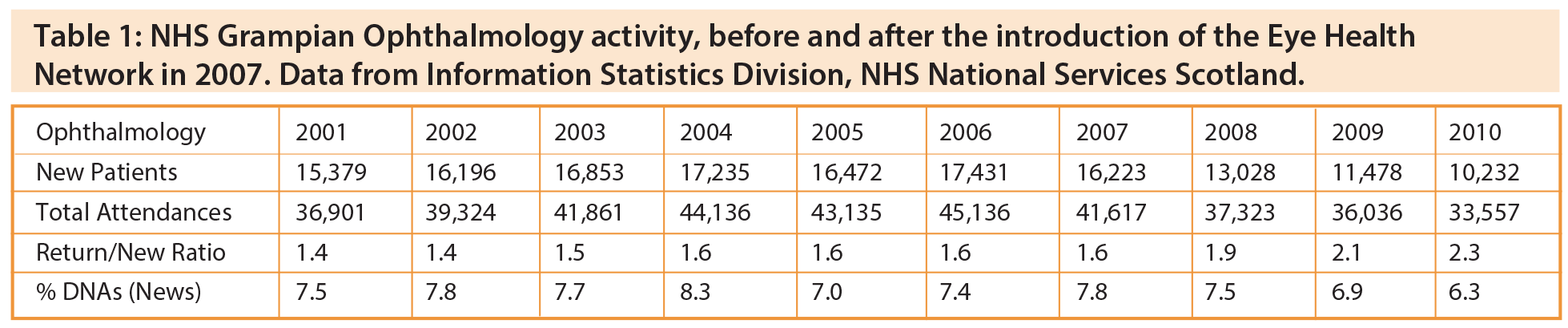

Prior to 2004 ophthalmology attendances in NHS Grampian were rising year on year (Table 1). Drivers included the introduction of retinal screening in 2002, photodynamic therapy for age-related macular degeneration in 2003 and the ageing demographic. The introduction of a community optometry glaucoma refinement scheme in 2004 seemed to staunch the rise, at least initially. The tide only really turned with the introduction of the new GOS contract in 2006, enabling postoperative cataract care and patients with ocular hypertension to be discharged to the community, and the introduction of the Eye Health Network in 2007. The introduction of an optical coherence tomography virtual clinic for diabetic macular oedema in 2008 had an additional modest benefit.

Figure 2: Rate of GOS eye examinations per 1000 population by NHS board;

year ending March 2013. Data from Information Statistics Division, NHS National Services Scotland.

Community optometry

Monitoring of NHS Grampian General Ophthalmic Services data, which is derived from payments to optometry practices, shows a different pattern. There was no significant change to the numbers being seen by community optometry before and after the Eye Health Network service change. NHS Grampian GOS figures continue to remain in line with other Health Boards in Scotland, despite the absence of an Eye Health Network or similar service arrangements in other Boards (Figure 2). We conclude that optometry had involvement with the majority of patients prior to the introduction of the Eye Health Network. However, clearer guidance and ready access to advice allows more patients to be treated to conclusion within primary care.

Discussion

The creation of the Eye Health Network has had a dramatic impact on the provision of eye care in NHS Grampian. Collaborative working has led to clarity between ophthalmology and optometry as to what can be managed in the community and what should be referred to hospital. Ophthalmology has come to a new understanding that it has responsibility for the eye care of all patients in NHS Grampian, not just those attending ophthalmology clinics. Optometry understands that ophthalmology genuinely wishes to work in partnership and that ophthalmology shares responsibility for the clinical care optometry delivered in the community.

This shared understanding, and the trust that the network generates, has led to an environment where optometry feels safe to fully step up to the professional responsibilities envisaged by the 2006 GOS contract. However, without the new funding arrangements this contract brought, it is doubtful that optometry would have been able to participate so fully in the delivery of eye care in the community.

The cornerstone to the network has been fast and effective communication. This has been engendered, not just through telephone advice, but also an NHSmail advice account and an electronic referral system that incorporates a simple mechanism where advice can flow directly to optometry indicating whether ophthalmology attendance is required, if not why not, and what the optometrist should advise the patient. This two-way flow of information is not only essential from a clinical governance point of view, but has been highly educational, leading to rapid up-skilling of optometry.

In 2014, NHS Grampian’s bespoke electronic referral system will be replaced by the role out throughout Scotland, of the same, one-way electronic referral system, currently used by general practice (SCI-Gateway), to enable optometry to refer to ophthalmology [3]. The Scottish Government Eye Health Integration Project has set a target of 95% of referrals from optometry to ophthalmology across Scotland being carried out through the new system by April 2014. This system does not include a mechanism for ophthalmology to freely communicate with optometry. Instead, only fixed messages ‘appointed routine, appointed urgent, awaiting information or not appointed’ are generated, with a dictated letter to be sent to optometry if appointment is not required. This is unlikely to encourage ophthalmology to fully utilise the ability of optometry to manage patients in the community.

The Eye Health Network has been in place for six years and continues to flourish. Whilst on its own in 2007, various initiatives in Scotland now foster closer relationships between ophthalmology and optometry, including the national introduction of Teach and Treat clinics funded by National Education for Scotland, SCI-Gateway referrals for optometry and the availability of prescription pads for independent optometry prescribers. The introduction of clinical management guidelines, similar to the network’s patient pathways, shows that the College of Optometry believes strongly that its profession should play an integral part in the delivery of eye care [4]. Lastly, the joint statements on the management of urgent eye care by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists and the College of Optometry strengthen our hope that NHS Grampian’s Eye Health Network will one day be one of many [5].

References

1. Optometry Scotland.

http://www.optometryscotland.org.uk.

Last accessed February 2014.

2. Delivering Better Health, Better Care Through Continuous Improvement: Lessons from the National Programmes. NHS Scotland.

http://www.scotland.gov.uk/

Resource/Doc/212120/0056427.pdf.

Last accessed February 2014.

3. Eye care integration: programme resources for NHS Scotland.

http://www.eyecareintegration.scot.nhs.uk.

Last accessed February 2014.

4. Clinical management guidelines. The College of Optometrists.

http://www.college-optometrists.org/en/

professional-standards/ clinical_management_guidelines/index.cfm.

Last accessed February 2014.

5. Guidance for commissioners. The Royal College of Optometrists.

http://www.college-optometrists.org/en/

commissioning/guidance-for-commissioners.cfm.

Last accessed February 2014.

TAKE HOME MESSAGE

-

Scotland’s 2006 General Ophthalmic Services Contract enabled optometry to become the first port of call for all eye problems.

-

Clearly defined network roles, responsibilities and pathways ensured appropriate use of optometry and ophthalmology capacity.

-

The key to effective partnership working is fast and effective communication.

-

A network facilitates mutual ownership, shared goals and enriched professional relationships.

Declaration of Competing Interests: None declared.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME