Steven Kerr of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh explores the medical career of Arthur Conan Doyle, his relationship with his mentor Joseph Bell and his fascination with ophthalmology.

Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle was born in Edinburgh on the 22 May 1859. By the time of his death 71 years later his name (minus the Ignatius) was to become associated with some of the most significant crime and adventure fiction the world had ever seen. Today, almost 90 years after his passing, Doyle remains among the most admired novelists, and is celebrated around the globe as the creator of arguably the most famous fictional sleuth of all time, Sherlock Holmes.

It is of course well-known that Doyle trained and worked in medicine before turning his hand to writing professionally, although whether as a child Doyle himself had intended to take either career path is debatable. Indeed, in his 1924 autobiography Memories and Adventures he recalls telling a schoolmaster of his ambition to become a civil engineer, only to receive the reply, “Well Doyle, you may be an engineer, but I don’t think you will ever be a civil one.[1]”

Later in the same book, Doyle writes that (having returned to Scotland from schooling in Stoneyhurst, Lancashire) “It had been determined that I should be a doctor – chiefly, I think, because Edinburgh was so famous a centre for medical learning [1].” While the description of Scotland’s capital is undoubtedly accurate, Doyle’s phrasing hardly suggests a person in sole control of his destiny at the time, although he would be acutely aware of the sacrifices made by his mother, Mary, to provide for her family despite the alcoholism and increasing mental illness of her husband, Charles Altamont Doyle.

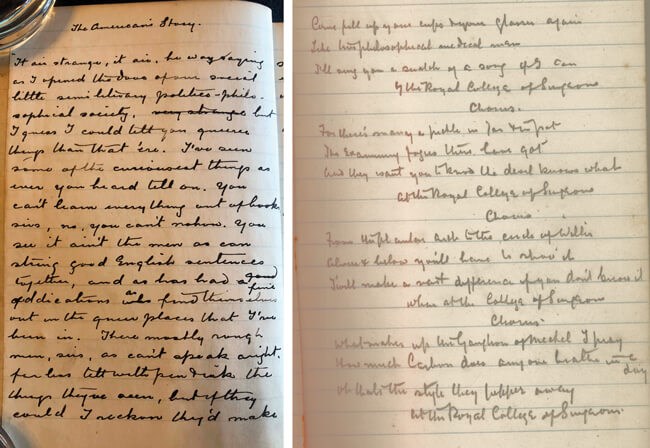

Left: Page 1 of handwritten draft The American’s Story. From the collections of The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh.

Right: ‘The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh’ – handwritten poem by Arthur Conan Doyle.

From the collections of The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh.

Arthur commenced studies at the University Medical School in 1876. He modestly claimed to be little more than average academically, describing himself as “always one of the ruck, neither lingering nor gaining.” Nonetheless, he graduated MB and CM August 1881 [2] and four years later added the advanced Doctor of Medicine degree [3]. More significantly though, it was during his university years that the student doctor took his first serious steps into the writing of fiction. In October 1879 he earned £3 from the weekly Edinburgh magazine Chambers’ Journal for his short adventure story The Mystery of Sasassa Valley. This was followed that same year by The American’s Tale, Doyle’s first to be published in the monthly London Society journal.

“It could be argued that almost as valuable to the degrees Doyle earned was his meeting certain lecturers, whose characters he found lent themselves very well to his literary creations”

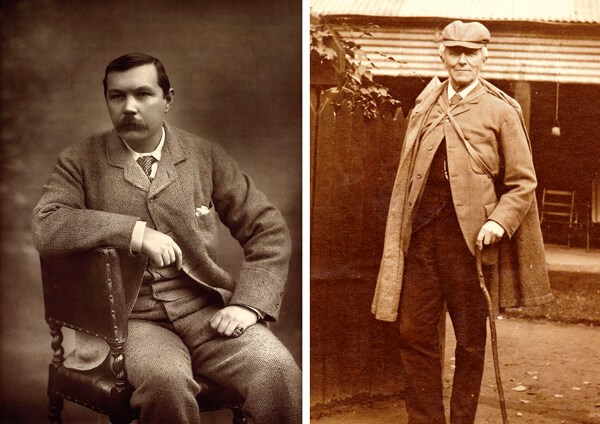

Left: Arthur Conan Doyle. Photographed by Herbert Rose Barraud, 1893.

Right: Joseph Bell in deerstalker. From the collections of The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh.

There is something pleasingly analogous about Doyle’s handwritten draft of The American’s Story (as Doyle’s initial title had it) and his gradual conversion from man of medicine to man of words, in that the story is written in a medical notebook. Entitled ‘Notes on Medicine Session 1879-80. Compiled from the Clinical Class from the infirmary wards, and from epitomes of the Systematic class’, the notebook – acquired by the Library of The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh in 2004 – includes revision notes on the constitutional complications of gout, treatments of rheumatism, and clinical details of named patients and their symptoms. But it also has 30 pages dedicated to the aforementioned short story (about the death of Joe Hawkins in Montana (“Alabama Joe as he was called thereabouts. A regular out and outer he was, ‘bout the darndest skunk as ever man clapt eyes on”) and a humorous poem celebrating the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh itself, the second verse of which reads:

‘For there’s many a pickle in jar and in pot;

The Examining fogies there have got;

And they want you to know the devil knows what;

At the Royal College of Surgeons.’

A third short story, The Gully of Bluemansdyke was published by London Society in 1881, the year of Doyle’s graduation.

Joseph Bell

Of his academic years, Doyle was to write in his autobiography that “There was no attempt at friendship, or even acquaintance, between professors and students at Edinburgh. It was a strictly business arrangement [1].” However, it could be argued that almost as valuable to the degrees he earned was his meeting certain lecturers, whose characters he found lent themselves very well to his literary creations. For example, there was William Rutherford, Professor of Physiology & Anatomy, and who partly inspired (both in physique and personality) the bearded, domineering zoologist Professor Challenger in The Lost World. But even more significantly, there was Joseph Bell.

Joseph Bell was the last of a great Edinburgh surgical family dynasty spanning over a century-and-a-half [4]. Born in Edinburgh in 1837, he was schooled at the Edinburgh Academy and qualified MD from the University in 1859. Probably destined to be a surgeon given his family history, Joseph immersed himself in a life of medicine, starting during his academic years when he served as President of The Royal Medical Society of Edinburgh, one of the oldest students’ societies in the world [5]. Like his great-grandfather, grandfather and father before him, he was to become a Fellow of The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, admitted in February 1863. He also served separate terms as Secretary and Treasurer of the same institution, eventually becoming RCSEd President in 1887. In addition he edited the Edinburgh Medical Journal for over 20 years.

“Specific diagnoses based on deduction also came readily to Bell, who regularly used real patients with which to test his students, challenging them to identify ailments through simple observation and logic”

In the operating theatre, Bell was an outstanding paediatric surgeon, and was an obvious choice to become the first surgeon to the new Department of Surgery in the Royal Hospital for Sick Children in 1887. His care of young patients was renowned, and often to the disregard of his own well-being, illustrated by the time when – as a young practitioner – he contracted diphtheria from a child patient [6]. In a diary entry from June 1864 Bell wrote: “Since Monday I have been confined to bed with pretty bad diptheric sore throat...which I probably acquired by direct contact from sucking child Brittain’s throat.”

He had inserted a pipette into the child’s windpipe and sucked out harmful mucus from the child’s throat, but in the process (and perhaps unsurprisingly) caught diphtheria himself. The illness was to leave Bell with a slight limp, noted by Doyle who was to describe his teacher as having “a jerky way of walking.” That said, in the same description of Bell there is also the suggestion of the classic image of Sherlock Holmes, perhaps reminiscent of the screen depictions by Basil Rathbone or Peter Cushing. “He was thin, wiry…with a high-nosed acute face, penetrating grey eyes and angular shoulders [1].”

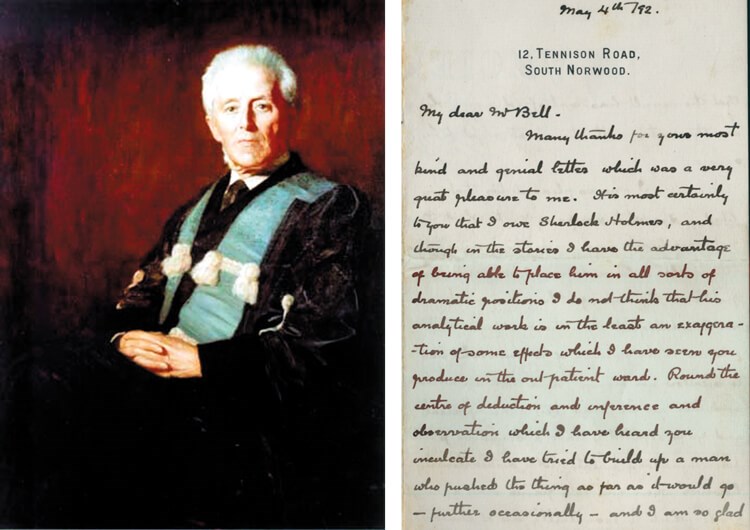

Left: Joseph Bell in FRCSEd gown. From the collections of The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh.

Right: Letter from Arthur Conan Doyle to Joseph Bell, 4 May 1892.

From the collections of The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh.

Joseph Bell’s early surgical career had involved working as assistant to the legendary James Syme, and he also served two years as demonstrator in anatomy to John Goodsir, the distinguished anatomist credited as the first to introduce the compound microscope to Edinburgh. Both Syme and Goodsir helped instil in Bell the importance of observation and attention to detail, and by the time he was appointed lecturer in surgery at the Extra Mural School of Medicine (run, not by the University, but conjointly by the surgeons and physicians of the two Edinburgh Royal Colleges), Bell was recognised among the capital’s medical students as not only a fine surgeon, but also something of a genius in diagnostic acumen.

One such student was Arthur Conan Doyle, who enrolled in Bell’s clinical surgery class in 1878 and quickly became enamoured with Bell’s often entertaining – almost playful – manner of demonstrating the value of observation. This was well illustrated by his legendary routine in which – extolling the benefits of using all five senses to observe – he would dip a finger into a bitter solution and taste the foul concoction. Wincing with revulsion, he would invite his students to do the same which, of course, they all did. He would then point out that each had failed this particular test of observation by not noticing that he had dipped his index finger into the solution, but his middle finger into his mouth.

Specific diagnoses based on deduction also came readily to Bell, who regularly used real patients with which to test his students, challenging them to identify ailments through simple observation and logic. On one occasion he demanded a diagnosis of a man with a peculiar limp, to which a nervous student suggested hip-joint disease. Bell’s response is truly Sherlockian.

“Hip-nothing! The man’s limp is not from his hip, but from his feet. Were you to observe closely, you would see that there are slits, cut by a knife, in those parts of the shoes where the pressure of the shoe is greatest against the foot. The man is a sufferer from corns, gentlemen. But he has not come here to be treated for corns. We are not chiropodists, gentlemen. His trouble is of a much more serious nature. His is a case of chronic alcoholism. The rubicund nose, the puffed, bloated face, the blood-shot eyes, the tremulous hands and twitching face muscles, the quick, pulsating temporal arteries. These deductions, gentlemen, must, however, be confirmed by absolute and concrete evidence. In this instance my diagnosis is confirmed by the fact of my seeing the neck of a whisky-bottle protruding from the patient’s right-hand coat pocket [5].”

It is also worth noting that Bell was no stranger to criminal investigative procedures. On several occasions throughout the 1870s he assisted Dr Henry Littlejohn, Edinburgh’s first Medical Officer of Health, Professor of Medical Jurisprudence and Chief Surgeon to the City Police. Perhaps the most famous of these cases was the 1878 murder of Elizabeth Chantrelle, poisoned by her French husband Eugene. In a scenario reminiscent of the fictional murder plots Doyle was to make his specialty, Eugene claimed to have found his wife in bed overcome by a gas leak. However, Littlejohn and Bell discovered that in the preceding months Chantrelle had purchased large quantities of opium from city pharmacists. They also traced a gasfitter who had worked on the Chantrelle home and who noted that the linguistics teacher had expressed a curious interest in the workings of the house’s gas supply. Nor did it go unnoticed that a large insurance policy was in place against Mrs Chantrelle’s life.

Duly found guilty and sentenced to hang, Chantrelle is said to have turned to the attending Littlejohn and muttered, “Give my compliments to Joe Bell. He did a good job in bringing me to the scaffold.” Ironically, through his crime Chantrelle himself was to inspire a legendary literary figure – Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll.

Although Doyle was to acknowledge in his autobiography that he thought of Bell’s “eagle face, of his curious ways, of his eerie trick of spotting details” [1] in 1887 when writing the first Sherlock Holmes story, A Study in Scarlet, it would be wrong to suggest Bell was the sole inspiration for Sherlock Holmes. The author recognised the influence that Edgar Allen Poe’s fictional French detective C. Auguste Dupin had on his work; the aforementioned Littlejohn (who lectured Doyle in forensic science) almost certainly played a part in the character’s development; and of course many will argue that the only person who can legitimately claim to be Sherlock Holmes is Doyle himself.

However, there can be little better primary evidence as to the sleuth’s inspiration than a letter from Arthur Conan Doyle to Joseph Bell, the lecturer who had become his friend, dated 4 May 1892, a year after a serialisation of Holmes stories in The Strand had gained national recognition. The letter, one of a set of seven held by the Library of The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh states: “It is most certainly to you that I owe Sherlock Holmes, and though in the stories I have the advantage of being able to place him in all sorts of dramatic positions I do not think that his analytical work is in the least an exaggeration of some effects which I have seen you produce in the outpatient ward [7].”

That same year Doyle was actually to let slip to a journalist (Harry How) the level of inspiration Bell had given him for Holmes. How wrote an article in The Strand naming Bell, which led to some consternation for his former student, as illustrated in another letter in which Doyle writes: “I fear that one effect of your identity being revealed to the readers of The Strand will be that you have ample opportunity for studying lunatic letters, and that part at least of the stream which pours upon me will be diverted to you [8].”

Arthur Conan Doyle and ophthalmology

Despite Doyle’s modesty about his academic skills, the oft-held belief that he was a failed physician who found professional redemption in writing is probably unfair. Soon after graduating in 1881, he found employment as ship’s surgeon on the steamship Mayumba on a voyage to the West Indies, caring for the health of some 30 passengers, until its return in early 1882 [2]. Doyle then moved to the south of England to commence private practice as a GP, first for a brief spell to Plymouth, and then to Portsmouth where he was to hold a respected – though not especially lucrative – practice for almost a decade in the suburb of Southsea, his income supplemented by around £10 to £15 a year from his writing [9].

It was during this time that he developed an interest in the treatment of the eye, and as well as performing eye tests he regularly – in Doyle’s own words – “amused himself” by correcting refractions and assisting noted Ophthalmologist Vernon Ford at the Portsmouth Eye and Ear Infirmary. In 1888, Doyle wrote to his sister, Lottie, indicating that he was considering a permanent switch to ophthalmology, and signalled his intention to study the specialty further in major European cities like Paris and Berlin, before setting up practice on Harley Street. This best-laid plan did not materialise as intended, however, and by 1890 Doyle was still in Southsea. However, on an unrelated trip to Berlin that year he had a chance meeting with dermatologist Sir Malcolm Morris. Morris had achieved Doyle’s aim of success on Harley Street and warned the younger man (now married and with an infant daughter) that he was wasting his medical career in the provinces. Learning of Doyle’s interest in the eye, Morris advised that Doyle abandon practice in England and study ophthalmology in Vienna.

“In 1888, Doyle wrote to his sister indicating that he was considering a permanent switch to ophthalmology, and signalled his intention to study the specialty further in major European cities”

Doyle took Morris at his word, and enrolled in classes at the city’s general hospital, the Allgemeines Krankenhaus. Alas, the training venture was not a successful one. Doyle quickly found both his practical experience in ophthalmology and his knowledge of technical German to be lacking. The intended six months stay in Austria’s capital lasted barely a third of that, and the family returned to England in March 1891. Doyle was, however, undeterred in his pursuit of specialising in ophthalmology, opening a practice in London only the following month and joining the Ophthalmological Society of the United Kingdom. He recognised that his skills would probably not extend to hugely complex surgeries of the eye, but he believed he could make a decent living on the more standard procedures of refractions and retinoscopy, of which he had experience, and which were often ignored by larger practices.

His new building also had the advantage of being large enough to accommodate a writing room. This was perhaps just as well, as patients visiting his surgery were to prove scarce in the proceeding weeks, and Doyle’s diary indicates that he abandoned the practice of ophthalmology less than a month after starting. The same year, The Strand magazine was founded and began regularly publishing his Sherlock Holmes stories, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Like so many episodes of Doyle’s personal life though, his brief experience in treatment of the eye provided him with material to use in his writing. For instance, in the 1892 Holmes short story The Adventure of Silver Blaze, “an ivory-handled knife with a very delicate, inflexible blade,” is found to have been used to inflict a small wound on the leg of the eponymous racehorse. In the story it is described by Holmes as “a very delicate blade devised for very delicate work,” and identified by his medically trained colleague Dr Watson as a cataract knife [10]. In addition, Dr James Ripley in the 1894 work The Doctors of Hoyland is described early in the tale as enjoying spending “half the night performing iridectomies and extractions upon the sheep’s eyes sent in by the village butcher, to the horror of his housekeeper, who had to remove the debris next morning.”

Thus, by supplying even the smallest points of reference to be included in the stories of one of the greatest authors of all time, Doyle’s brief foray into ophthalmology can probably be considered a successful one.

References

*Title of Article - Inscription on the grave of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930).

1. Doyle AC: Memories and adventures. Wordsworth Editions: London, UK; 2007.

2. Lycett A: Conan Doyle: the man who created Sherlock Holmes. Weidenfeld & Nicolson: London, UK; 2007.

3. Ravin JG, Migdal C. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle: the author was an ophthalmologist. Surv Ophthalmol 1995;40(3):237-44.

4. Macintyre I, MacLaren I (eds): Surgeons Lives, Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. An anthology of College Fellows over 500 years. The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK; 2005.

5. Liebow EM: Dr. Joe Bell: model for Sherlock Holmes. University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, USA; 1982.

6. Mackaill A, Kemp, D: Conan Doyle & Joseph Bell: the real Sherlock Holmes. The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK; 2007.

7. Letter from Arthur Conan Doyle to Joseph Bell. May 1892. Held by The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. Ref: GD 16/1/2/1/2

8. Letter from Arthur Conan Doyle to Joseph Bell. May 1892. Held by The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. Ref: GD 16/1/2/1/5

9. Snyder C. There’s money in ears, but the eye is a gold mine: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s brief career in ophthalmology. Arch Ophthalmol 1971;85(3):359-65.

10. Craig PC. Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes through the eyes of an ophthalmologist. Trans Pa Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 1972;25(1):42-3.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME