The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) each conduct independent assessments of benefit-risk profile when evaluating applications to market new or modified medicines, and their respective decision-making is guided by distinct legislation, procedures and societal expectations [1]. Expert contributions from healthcare professionals as well as patients’ organisations represent integral components of regulatory drug evaluations.

The author outlines regulatory approaches to the authorisation of new medicines in the European Union and US, explaining initiatives designed to bring innovative novel drugs faster to market, and charts recent progress made in the ophthalmology space.

Understanding the centralised European regulatory system

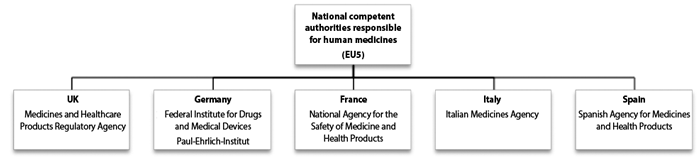

The EMA is the body in the European Union (EU) responsible for the evaluation, supervision and pharmacovigilance of medicine products. The EMA also supervises the safety of medicines in the EU after they have been authorised, and can also give scientific opinions on medicines at the request of member states or the European Commission. Following authorisation, EMA and the national competent authorities of the EU continue to monitor the benefits and risks associated with an approved medicine in real life, and provide updated safety advice where applicable to enable informed decisions when using or prescribing a medicine. Figure 1 shows the main scientific committees of the EMA and Figure 2 details the national competent authorities of the EU5 countries.

Figure 1: EMA and its scientific committees.

There are two main methods of securing marketing authorisation for a medicine. The centralised authorisation procedure, via the European Commission after EMA evaluation, results in a single marketing authorisation valid through the EU. The other route is via national authorisation procedures in individual EU member states, through national authorisation, mutual-recognition procedure, or decentralised procedure. Some medicines for specific disease groups are subject to mandatory evaluation by EMA, such as rare diseases, HIV, cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, diabetes, auto-immune and viral diseases, all biotech products, gene therapy, monoclonal antibodies and other innovative products.

The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) is responsible for preparing the EMA’s opinions on all matters concerning medicines for human use. The CHMP conducts the initial assessment of medicines for which an EU-wide marketing authorisation is sought, and is responsible for several post-authorisation and maintenance activities, including the assessment of any modifications or extensions (variations for additional new indications) to an existing marketing authorisation.

The evaluation by the Agency’s scientific committees takes up to 210 active days plus possible ‘clock stops’ (for the applicant to provide answers to questions from the CHMP), at the end of which the CHMP adopts an opinion on whether the medicine should be marketed or not. This opinion is then transmitted to the European Commission, which has the ultimate authority for granting marketing authorisations in the EU. Under EMA’s accelerated assessment mechanism, the time limit of 210 days may be reduced to 150 days. After a request for accelerated assessment has been granted, at any time during the marketing authorisation application evaluation, if the CHMP considers that it is no longer appropriate to conduct an accelerated assessment the CHMP may decide to continue the assessment under standard centralised procedure timelines.

A European public assessment report (EPAR) is published by the CHMP for every centrally authorised medicine that is granted a marketing authorisation. This provides a full scientific assessment report supporting the CHMP’s opinion in favour of granting the authorisation.

Progress made in 2015 with ophthalmology medicines

In 2015, the EMA recommended 93 medicines for marketing authorisation, including 39 new active substances (one third for the treatment of cancer). There were 54 extensions of therapeutic indications, as well as approval of 18 orphan medicines, and three medicines authorised under exceptional circumstances. Table 1 shows ophthalmology medicines which received an opinion from the EMA in 2015 (new marketing authorisation applications and extensions of indications).

Orphan designation is assigned by the EMA to a medicine intended for use in treating a rare condition, defined as one affecting not more than five in 10,000 people in the European Union. The medicine must fulfill certain criteria for designation as an orphan medicine so that it can benefit from incentives such as protection from competition once on the market. Designated orphan drugs are products that are still under investigation and are considered for orphan designation on the basis of potential activity. Demonstration of quality, safety and efficacy is necessary before a product with orphan designation can be granted a marketing authorisation.

Sponsors who are successful in obtaining orphan designation for a particular drug benefit from protocol assistance and, if subsequently approved, a 10-year market exclusivity. New orphan medicines securing marketing authorisation by the EMA’s CHMP in 2015 include Unituxin (dinutuximab) for patients with brain cancer (neuroblastoma), Blincyto (blinatumomab) for patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, and Hetlioz (tasimelteon) for blind adults with sleep-wake disorder.

Tasimelteon was designated an orphan medicine in 2011. Following marketing authorisation approval last year, it is indicated for the treatment of Non-24-Hour Sleep-Wake Disorder (Non-24) in totally blind adults. Tasimelteon is a dual melatonin receptor agonist (DMRA) with selective agonist activity at the MT1 and MT2 receptors believed to act in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. The Hetlioz EPAR notes that Non-24 should be suspected in any totally blind individual who presents with a chronic history of sleep-wake disorder. As many as 70% of totally blind patients are expected to have Non-24, with an estimated prevalence of 1.5 to 2.2 persons per 10,000 in the EU. Study data showed significant improvement with daily dosing of tasimelteon compared with placebo, both in increasing night-time sleep and decreasing daytime-sleep duration.

Orphan designation was granted last year by the European Commission to Italian firm Dompé farmaceutici for recombinant human nerve growth factor for the treatment of neurotrophic keratitis. Estimated to affect approximately 4.2 in 10,000 people (equivalent to around 215,000 people), neurotrophic keratitis is a condition of the cornea caused by damage to the trigeminal nerve. The nerve damage results in a lack of sensitivity in the cornea, and to dryness, ulceration and scarring that interferes with vision. Clinical trials with recombinant human nerve growth factor in patients with neurotrophic keratitis are ongoing. Orphan designation of the medicine had been granted in the United States for neurotrophic keratitis.

Hybrid medicine is defined by the EMA as a drug that is similar to an authorised medicine containing the same active substance, but where there are certain differences between the two medicines such as strength, indication or pharmaceutical form.

The EU granted marketing authorisation last year for Raxone (idebenone, Santhera Pharmaceuticals), the first approved medicine for the treatment of visual impairment in adolescent and adult patients with Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON). The application for a marketing authorisation used Mnesis (45mg tablets) as a ‘reference medicine’, authorised since 1993 in Italy for treatment of cognitive and behavioural deficits due to cerebral pathologies of vascular or degenerative origin. Raxone contains the same active substance idebenone but at a different strength.

The proposed mechanism of action in LHON is that idebenone mitigates inactive-but-viable retinal ganglion cell dysfunction by shuttling electrons onto complex III of the mitochondrial transport chain, thereby bypassing the deficient complex I, restoring production of cellular energy and decreasing oxidative stress in affected cells. Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy is a maternally inherited disease characterised by acute or sub-acute painless vision loss in one eye, generally followed by a similar vision loss in the second eye, typically within two to four months. Most patients (~97%) progress to a bilateral VA of 20/200 or worse within one year of disease onset. The prevalence of LHON is estimated at between one in 15,000 and one in 50,000 worldwide.

Efficacy data supporting Raxone for LHON come from a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase II trial, RHODOS, and from an open label expanded access program and a natural history case record survey. The data demonstrated a consistent pattern whereby a larger proportion of patients treated with Raxone (two tablets three times a day) had vision improvement compared with untreated or placebo-treated patients. Raxone was authorised under ‘exceptional circumstances’, because it has not been possible to obtain complete information about the drug due to the rarity of LHON.

Figure 2: The EMA committees contain members nominated by the medicines regulatory authorities of the EU Member States (the ‘national competent authorities’) and four committees have members representing patients’ organisations. The national competent authorities of the EU5 countries is shown above.

Over the pond: novel drug approvals expedited in the United States

The FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) is responsible for ensuring that prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) drugs marketed in the United States are safe and effective.

When companies (sponsors) submit a new drug application (NDA) to the FDA to introduce a new drug product into the US market, it is the responsibility of the company seeking to market a drug to test it and submit evidence that it is safe and effective. The NDA application will contain data from specific technical viewpoints for review, including chemistry, pharmacology, medical, biopharmaceutics and statistics. A team of CDER scientists review the sponsoring company’s NDA containing study data, proposed labeling and regulatory dossier. If positive, an FDA approved label will outline the official description of a drug product, such as treatment indication, who should take it, adverse events, and patient safety information.

An Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) refers to generic drug applications, abbreviated because sponsors are generally not required to include preclinical and clinical data to establish safety and effectiveness. A generic drug product must contain identical amounts of the same active ingredient(s) as the brand name product. Applicants must demonstrate scientifically that its product performs in the same manner as the innovator drug and is therapeutically equivalent.

The CDER approved 45 novel drugs last year, approved as new molecular entities (NMEs) under NDAs, or as new therapeutic biologics under Biologics License Applications (BLAs). The corresponding figure for 2010 was 21, although submissions of applications for NMEs and novel new BLAs by the biopharmaceutical industry have generally remained relatively stable over the past 10 years.

While maintaining rigorous standards for demonstration of effectiveness and safety, CDER has used several regulatory methods to help bring innovative novel drugs faster to market, including four expedited development and review pathways:

- Fast track: refers to drugs with a new and unique mechanism for treating a medical condition, with potential to address unmet medical needs.

- Breakthrough therapies: where preliminary clinical evidence demonstrates that the drug may result in substantial improvement on at least one clinically significant endpoint (i.e. study result) over other available therapies. Breakthrough status is designed to help shorten development time of a potential new therapy.

- Priority review: a designation used for novel new drugs that may offer a potential to provide a significant advance over existing medical care, entailing a FDA review target of within six months instead of the standard review period of 10 months.

- Accelerated approval: refers to early approval based on markers that predict a reasonable benefit, and once granted, the drug must undergo additional testing to confirm that clinical benefit.

The accelerated approval programme allows early approval of a drug for a serious or life-threatening illness that offers a benefit over current treatments. Other FDA drug review and approval designations include:

- First-in-class: a drug with a new and unique mechanism for treating a medical condition (representing 36% of novel drugs approved in 2015).

- Orphan drugs: approved for small populations of patients with rare diseases; 47% of novel drugs approved in 2015 were approved to treat rare or ‘orphan’ diseases affecting 200,000 or fewer Americans.

- First cycle: drugs approved without request for additional information that would delay approval and lead to another review cycle (87% of new drugs approved in 2015).

- First approved in US: drugs approved in the United States before receiving approval in any other country.

A cohort study of FDA-approved novel therapeutics between 1987 and 2014 showed that many newly approved drugs by the FDA have been associated with an increasing number of expedited development or reviews programmes [2]. Of 774 drugs approved by the FDA during the study period, one third represented innovative first-in-class agents. Overall, the FDA drug review and approval process has improved, with the median approval time for new molecular drugs reduced from 19 months to 10 months.

The priority review process by the US FDA applies to drugs considered a significant improvement over the available alternatives, while under the EMA framework, accelerated approval applies to a medicine that is of major public health interest. A study of all priority review drugs approved by both regulatory agencies in the period 1999-2011 shows a significantly lower average review time by the FDA (9.2 ± 8.4 months) than the EMA average review time (14.6 ± 4.0 months) [3]. Almost two-thirds (64%) of the novel drugs approved by the FDA in 2015 were ‘first approved in US’.

Both the EMA and FDA regulatory agencies share information on marketing authorisation procedures, changes to marketing authorisations and post-authorisation surveillance for products under review both in the US and in the EU. This includes the exchange of assessment reports and review documents and ad-hoc exchanges between US and EU experts.

Breaking development: PRIME time at EMA

A scheme to allow for quicker development and accelerated assessment of medicines of major public health interest was introduced in the first quarter of 2016 by EMA. Known as PRIME (PRIority MEdicines), the scheme will provide enhanced scientific and regulatory support to companies developing priority medicines, defined as drugs that may offer new therapeutic options where no current treatment options exist, or offer a major therapeutic advantage over existing treatments.

The objective is accelerated assessment of new priority medicines to benefit patients as early as possible, and encourage medicine developers to focus on treatments with a potential significant benefit. These aims are aligned with a proposed EU Medicines Agencies Network Strategy to 2020, actively supporting patient-focused innovation and timely patient access to new beneficial and safe medicines.

Eligibility criteria for PRIME are expected to mirror those of the accelerated assessment procedure. That means demonstrating preliminary clinical evidence indicating the medicine has the potential to bring significant benefits to patients with unmet medical needs, and hence be of major public health interest. The PRIME scheme is limited to innovative products under development and yet to be placed on the market, i.e. where there is an intention to apply for an initial marketing authorisation through the centralised procedure.

References

1. Ciociola AA, Cohen LB, Kulkarni P; FDA-Related Matters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. How drugs are developed and approved by the FDA: current process and future directions. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109(5):620-3.

2. Alqahtani S, Seoane-Vazquez E, Rodriguez-Monguio R, Eguale T. Priority review drugs approved by the FDA and the EMA: time for international regulatory harmonization of pharmaceuticals? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2015;24(7):709-15.

3. Kesselheim AS, Wang B, Franklin JM, Darrow JJ. Trends in utilization of FDA expedited drug development and approval programs, 1987-2014: cohort study. BMJ 2015;351:h4633.

TAKE HOME MESSAGE

-

A European public assessment report (EPAR) is published by the CHMP for every centrally authorised medicine that is granted a marketing authorisation, providing a full scientific assessment report.

-

Orphan designation is assigned to a medicine intended for use in treating a rare condition, defined as one affecting not more than five in 10,000 people in the European Union; sponsors who are successful in obtaining orphan designation for a particular drug benefit from protocol assistance and, if subsequently approved, a 10-year market exclusivity.

-

The EMA introduced PRIME in the first quarter of 2016, a scheme designed to allow for quicker development and accelerated assessment of medicines of major public health interest.

-

The FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research has used several regulatory methods to help bring innovative novel drugs faster to market, including four expedited development and review pathways: fast track, breakthrough, priority review and accelerated approval.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME