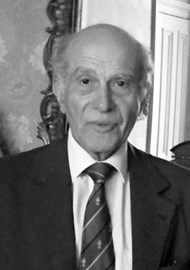

On the sad passing of Eye News’ first editor and long-term contributor JF (Barry) Cullen, his friend Hector Chawla takes a look at the life and career of this effervescent character and giant of the ophthalmology world.

Barry Cullen was a titan of ophthalmology though the very notion would never have crossed his mind because he was one of those rare figures who pass through life, modestly unaware of the impact they have on a world that is always the better for their having been in it.

But titans have to begin somewhere, and Barry took the first steps at University College Dublin where he qualified in1952. After the registration year, he moved into his chosen speciality at the Dublin Eye and Ear Hospital then on to Newcastle, from which centre he was allowed to present himself successfully for the Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons of England six months short of actually being eligible to sit it – an honour which merely confirmed the pattern of everything in a hurry.

In 2018 the University of Edinburgh awarded Barry an inscribed silver salver tray

to thank him for his excellent teaching over the years.

Then followed a career-changing year in the Wilmer Institute at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where Frank Walsh – a pioneer in neuro-ophthalmology – drew him into the mysteries of the eye and the brain, leaving him spellbound by the subject for the remainder of his life.

Returning to the UK, however, brought him face to face with the disheartening task of searching for a permanent post when, out of the blue, Edinburgh University advertised for a Senior Lecturer in Ophthalmology and his appointment began a close association with the Professor, George Scott, who entrusted Barry with the internal planning of the new Eye Pavilion which was due to open in 1969.

As though that were not enough, at the same time he turned his attention to the medical staff. He wanted them to be trained and not just left to absorb the subject by service driven osmosis. The most junior doctor in the professorial unit was therefore relieved of commitments in the clinics for six months in the first year. The Friday afternoon teaching sessions he began and ran are still a sacrosanct part of the ocular week. As for the nurses, he realised that by promoting Edinburgh as the centre for the Ophthalmic Nursing Diploma, he would attract the best nurses who, once trained, might be persuaded to stay and he pressed those with lower qualifications to aim for higher ones, the acquisition of which he then facilitated. Such concern for staff welfare, not just the healthcare professionals, was justly appreciated by everyone on the hospital payroll.

(L-R) JF Cullen, Dr Sohan Singh Hayreh, Princess Alexandra, Professor George Scott, October 1969.

Barry was an effervescent character, radiating enthusiasm and a chuckle, more like a cackle, was never far away. He was first described to me as a blur, talking rapidly. The explanation for this asynchrony between brain and tongue was simple; his thought processes, juggling with several subjects at any one time, were always too rapid for his words which never quite caught up and were certainly too rapid to stop him from saying “gambit” when he really meant “gamut”. One learned never to take his first answer to any question as definitive because he would be thinking of something else when he replied. The key technique was to pause until it was considered possible that the question and answer might be in alignment.

Senior staff PAEP 1991: Back row from left; M Chisolm, J Simmonds, S Abbott, P Gibson, A Harper, M Studley,

B Snowden, S Gairns. Front row from left; B Fleck, B Dhillon, S Bartholomew, JF Cullen, H Chawla, A Adams, G Millar.

But his genial flood of words concealed a serious mind, ever reflecting on how to improve the quality of patient care. He was one of the first to foresee the age of the sub-specialist, to recognise that certain ocular disorders were becoming too complicated for the generalist and that the days when everyone would have a go at whatever surgical problem presented, now belonged to the1930s. However, reforming medical practice sanctified by long tradition, was rather like swimming for the shore against an ebb tide. Yet he persisted and his plans for the ophthalmology of tomorrow were certainly not lost on the doctors of tomorrow – the medical students. Like the Pied Piper he enticed a procession of the better graduates to follow him into the labyrinths of the eye from where they never escaped. And it was not only medical students from Edinburgh. The message spread along the pre-examination grape-vine, and from all corners of the globe came the response – the Far East, the Middle East, Africa, Europe. In due course, these trainees returned home, to be replaced again and yet again. Such a cosmopolitan influx, drawn to Edinburgh by Barry, naturally expected to find a department equipped with the latest. But ophthalmology is an expensive speciality and although money was forever scarce, Barry always seemed to find a way to loosen the purse-strings – a touch of intrigue, a cascade of honeyed words and lo, Edinburgh was the first centre in the UK outside Moorfields to have an Argon Laser. Somewhat later, in a now established pattern, he unearthed sufficient funds to build a new operating theatre.

As well as being expensive, the hallmark of an eye hospital is a very crowded out-patient department. Barry’s clinics were, as might be guessed, the most crowded of all and generally conducted in an atmosphere of anxiety allaying good humour. The action would spread from the consulting room, to the ante-room, to along the corridor to the telephone – the patient, a cloud of medical students, trainees, opticians, staff in search of a decision and Barry – flitting between like the Scarlet Pimpernel, sought here, sought there, sought everywhere.

Barry and Lakana Kumar Thavaratnam at the Singapore National Eye Centre.

In his chosen field he was supreme, reserving an amused tolerance for those who could not come to any intracranial conclusion before they had first deployed complicated radiology and indeed sometimes after they had, when he then provided them with a diagnosis from the history, over the telephone.

Yet despite the pressing demands for his special expertise he still found time for other interests in the correction of drooping eyelids in children and corneal reconstruction. And if that were not enough, there were diabetic eye disease, chairing the College Examination Committee, meticulously looking after the funds of the Ross Foundation Charity and helping to launch Eye News. Not to be forgotten is, that in addition to all that, he was a prime mover in identifying the relationship between temporal arteritis and ischaemic optic neuropathy – a seminal contribution to the prevention of irreversible visual loss.

When he retired in in 1994, his unique importance to Edinburgh was celebrated and his departure lamented at a dinner that filled the great hall of the College of Surgeons. But retirement turned out to mean an invitation to Singapore for two years that went on to become seventeen. The department of neuro-ophthalmology there, that he created from scratch, raised the name of the National Eye Centre as a celebrated referral unit and the Centre responded by creating the Barry Cullen International Fellowship to fund and foster sub-speciality training. As in Edinburgh, it was concern for the education and the future placement of his pupils in Singapore that turned Barry into an iconic figure who was treated by his new family with God like reverence and deep grateful affection, attested by the tributes that poured in from the Far East when the news of his death broke.

Politics never far away, he played a vital role as ambassador, furthering the interests of the Edinburgh College of Surgeons in setting up joint examinations with Singapore, Malaysia and Hong Kong. The College, in addition to the honorary FRCSEd it had conferred years before, awarded him its highest honour – the Gold medal, this latter being but one of a catalogue of accolades that would require a separate tribute to list.

Although it might be tempting to think it was all work and no play, that would not be true. He was equally competent at the bridge table and on the golf course. He began the Scottish Ophthalmological Golfing Society (SOGS) and conjured forth a silver cup from some hospital in Glasgow as a trophy.

I owe my career to Barry. He opened doors for me which he had first bothered to find, for a retinal fellowship in America, then discovered further doors to open on my return. Similar claims can be made by just about every trainee who worked with him. His death was shockingly swift, but it was as he would have wanted and it spared him the indignities of old age.

He was a towering figure in medicine, a man of deep principle and one whom it was very easy to love. He leaves behind him a very close-knit family – Ann whom he married 66 years ago, Paul, Stephen, twins David and Peter, Sally and 11 grandchildren. He also leaves a legacy of professional skill, compassion, care for patients and staff and devotion to his subject as revealed by his myriad papers in major journals, the last as recent as 2019. He was too humble to think himself in any way special. Well, he was right about most things, but on that point he was wrong.

(L-R) Baljean Dhillon, Barry Cullen and Hector Chawla.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME