The management of neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD) has advanced dramatically over the past seven years, with the introduction of targeted new therapies that successfully maintain or improve vision in a majority of affected individuals.

It’s a fast moving field, with newer therapeutic options and alternative dosing regimens available, combined with a better understanding of treatment response and the role of retinal imaging in assessing re-treatment need. Recent updated guidance recommendations from European and UK retina specialists respectively help consolidate evidence and current expert opinion on diagnosis, treatment and follow-up in clinical practice.

Inhibitors of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) now represent standard of therapy for multiple malignancies in several tumour types. There has also been a dramatic benefit in intraocular neovascular diseases, such as exudative or wet AMD, following treatment with ophthalmic anti-VEGF therapies ranibizumab, aflibercept and unlicensed intravitreal bevacizumab. Indeed, nAMD may no longer be the leading cause of blindness in people over the age of 50 years where access to ophthalmic VEGF inhibitors is available.

Euretina guidance confirms ‘timing matters’ in first-line management

The European Society of Retina Specialists (EURETINA) has prepared fresh guidance for the management of nAMD. Prof Ursula Schmidt-Erfurth, from Austria, outlined principal recommendations from the planned guidance in a scientific session presentation during the 13th EURETINA congress in Hamburg, Germany, 26th September, 2013.

Most patients with nAMD who are treated with intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy are successfully controlled. Study data show a 50% reduction in the incidence of AMD-associated legal blindness in Denmark from 52.2 to 25.7 per 100,000 in people aged 50 years or older over the 10 years to 2010, with a marked and sustained decline from 2006, coinciding with the EU marketing authorisation of intravitreal ranibizumab [1]. Incidence of legal blindness attributed to other causes decreased by 33%, most of the decline occurring between 2000 and 2006.

“While highly effective, anti-VEGF therapy for nAMD requires repeated retreatment activity in a life-long strategy.”

Despite clear benefit, studies of real-world clinical practice suggest undertreatment and undermonitoring of nAMD. In an observational study involving 551 patients followed by 16 ophthalmologists, 12 months of intravitreal ranibizumab treatment induced an overall mean visual acuity gain of 3.2±14.8 letters, with 19.6% gaining more than three lines of vision [2]. Less than 40% of patients received the recommended loading dose of three initial monthly injections. Only 4.4% of patients had regular follow-up and none were monitored monthly as stipulated in the guidelines. The average visit number was 8.6, with an average injection rate of 5.1. Poor compliance with treatment recommendations was reflected in mediocre outcomes, noted Lumiere study authors.

While highly effective, anti-VEGF therapy for nAMD requires repeated re-treatment activity in a life-long strategy. The aim of the updated EURETINA guidance is to provide efficient, practical and economic recommendations for managing nAMD, including diagnosis and therapy, applicable for the entire population and all subgroups, at all times and locations. Anti-VEGF therapy is the first-line therapy in neovascular AMD, notes EURETINA guidance. The following subsections summarise headline opinion and evidence regarding specific anti-VEGF treatments, as well as recommendations on diagnosis and follow-up [3].

First-line anti-VEGF therapy: efficacy and durability

Ranibizumab

Treatment outcomes in a monthly treatment / monitoring strategy utilising spectral domain (SD)-ocular coherence tomography (OCT) are excellent. Higher dosing does not improve visual benefit, although higher dosing with ranibizumab may optimise durability comparable to a bimonthly treatment regimen. The retina becomes flatter over time with monthly and pro re nata (PRN) strategies, while best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) declines slowly.

Bevacizumab

The best results using unlicensed intravitreal bevacizumab are obtained with a fixed monthly treatment regimen. There is a slight decline in visual acuity gains with PRN dosing, while monthly monitoring is mandatory. Evaluation of secondary endpoints, including absence of fluid on OCT and change in lesion size over 24 months, significantly favoured ranibizumab therapy and a monthly regimen. For equal results, more bevacizumab injections are needed.

Aflibercept

Pivotal phase III clinical studies demonstrate that, by 52 weeks, the efficacy and safety of aflibercept 2mg every eight weeks (2q8, after three monthly loading doses) was comparable to that of ranibizumab 0.5mg every four weeks. Non-inferiority of aflibercept compared to ranibizumab for prevention of moderate vision loss was established. Treatment with intravitreal aflibercept was found to be well tolerated across all dose groups through week 96. Following 52 weeks’ proactive treatment, efficacy was largely maintained for the remainder of the study using a modified quarterly retreatment schedule. The data suggest that, after one year of aflibercept therapy, it may be possible to extend the treatment intervals based on patients’ individual visual and anatomic outcomes. That said, continuous dosing may provide the best vision outcomes.

Results of the pivotal VIEW studies show that, at 96 weeks, aflibercept and ranibizumab were equally effective in improving BCVA and preventing BCVA loss [4]. The 2q8 aflibercept group was similar to the ranibizumab-treated group in visual acuity outcomes during 96 weeks, but with an average of five fewer injections overall.

Efficacy and durability differ slightly

All intravitreal anti-VEGF substances (ranibizumab, bevacizumab, aflibercept) are efficient in the treatment of nAMD. Efficacy and durability differ slightly, noted Prof Schmidt-Erfurth. This was summed up in a concise but controversial appraisal: aflibercept > ranibizumab > bevacizumab. That said, it was observed that, with a bi-monthly dosing strategy, these modest differences are ‘irrelevant’. There is a slight loss in benefit with PRN approaches; all PRN strategies reduce visual gain, despite monthly monitoring. Morphologic biomarkers help to indicate prognosis and management needs. Timing is crucial and treat-and-extend approaches represent an approximation only. Geographic atrophy was seen in 28% of nAMD patients treated on a monthly basis.

A multicentre cohort study (SEVEN-UP) assessed seven-year outcomes in 65 ranibizumab-treated patients originally enrolled in the phase III clinical trials ANCHOR and MARINA and the open-label extension trial HORIZON [5]. Approximately seven years (mean 7.3 years) after trial entry, 37% of study eyes met the primary endpoint of 20/70 or better BCVA. Compared with baseline, almost half (43%) of eyes were stable, whereas one third declined by 15 letters or more. These findings indicate that even following long-term anti-VEGF treatment, nAMD patients are still at risk for substantial visual decline.

While a fixed monthly dosing and monitoring regimen of ranibizumab has shown to provide good visual acuity (VA) gains, results from different clinical trials demonstrate that monthly monitoring and individualised dosing can produce similar VA results with lesser dosing. A post-hoc sub-analysis of the EXCITE study suggests that early visual response to ranibizumab therapy may predict future treatment requirements [6]. This analysis categorised patients based on VA response after three months of treatment, to determine if early response to ranibizumab will be able to predict any differences in month 12 treatment outcomes in patients receiving monthly versus quarterly dosing.

Irrespective of subsequent monthly or quarterly dosing of ranibizumab, patients from categories one and three maintained the initial VA gain achieved at month three. However, in the overall study population, the proportion of patients with no worse than a four letter reduction was larger in the monthly dosage group (77%) compared with the quarterly dosage group (65%; p=0.034). In patients who gained ≥15 letters at month three, there was little difference that suggested additional benefit of monthly dosing over the quarterly dosing with respect to the 12 month VA outcome. Early VA losers, however, showed better VA stabilisation with continued monthly dosing, indicating that such patients may require more intensive follow-up and retreatment whilst on ranibizumab treatment than those who demonstrated good initial VA response.

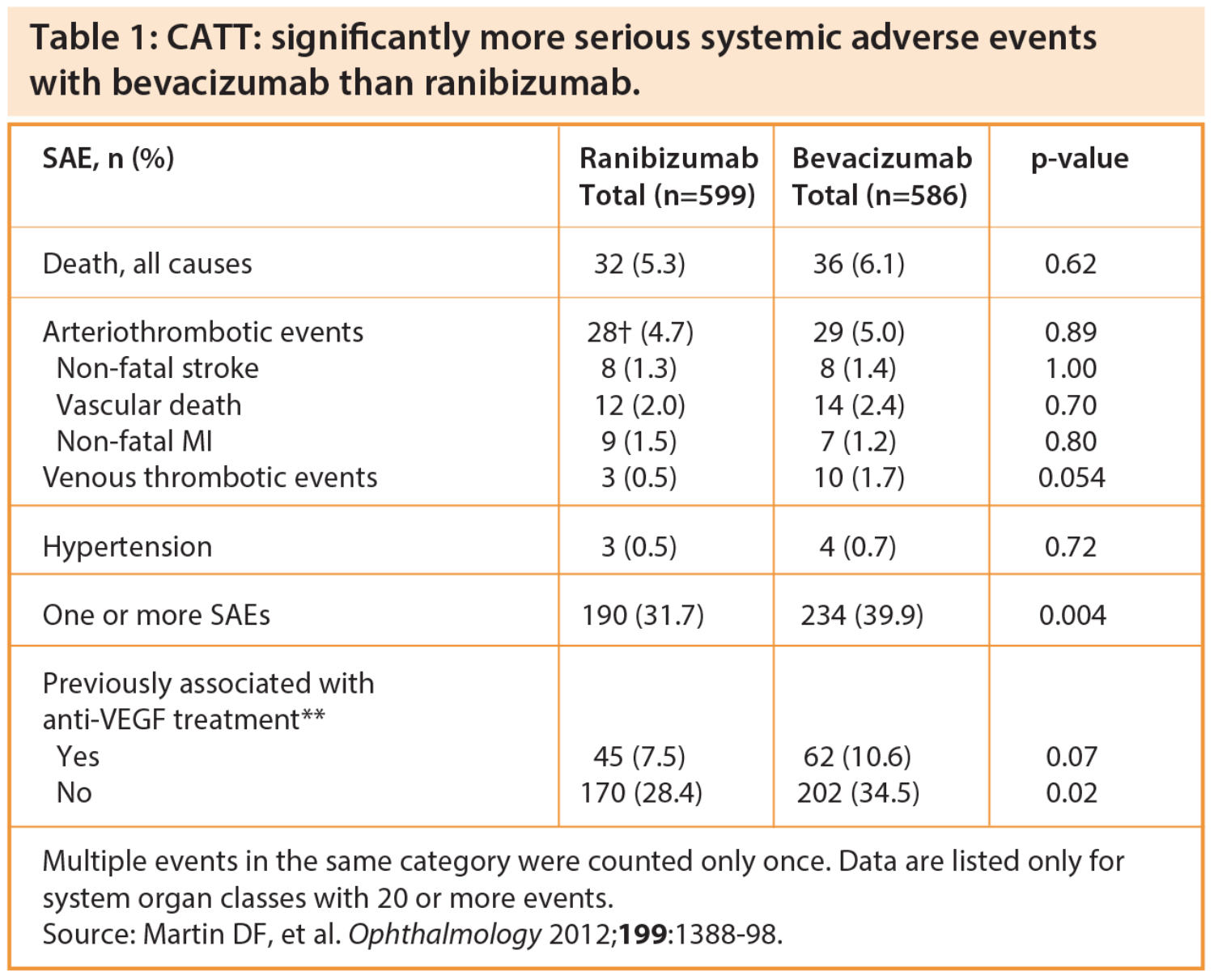

First-line anti-VEGF therapy: safety

The Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trial (CATT) highlighted significantly more serious systemic adverse events with bevacizumab than ranibizumab in nAMD patients (Table 1). Based on these data, noted Prof Schmidt-Erfurth, for every 12 patients treated with bevacizumab instead of ranibizumab, one patient would experience a serious systemic adverse event (number needed to harm = 12.2 [95% CI, 7.3-36.3]). There have also been geographic reporting clusters of severe ocular adverse events associated with intravitreal bevacizumab treatment.

Patients with AMD may be at increased higher risk of certain systemic adverse events such as stroke or arterial thromboembolic events (ATEs). Trials evaluating ranibizumab in the treatment of AMD suggest a possibility of increased stroke risk with intravitreal anti-VEGF treatment, particularly in patients with a history of stroke. Anti-VEGF compounds bevacizumab and aflibercept contain Fc (fragment crystallisable) portions and are associated with increased systemic exposure compared to ranibizumab. Intravitreal bevacizumab is associated with significant reductions in plasma VEGF levels. Additional studies involving large patient populations and extended follow-up are necessary to better assess serious but infrequent adverse events such as stroke or endophthalmitis.

A pooled safety analysis of more than 4,000 patients with nAMD, drawn from clinical practice registries in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and Sweden, found that ranibizumab has a low rate of events related to the potential (systemic) effects of VEGF inhibitors or the injection procedure [7]. The most frequent overall ocular events of particular interest were retinal pigment epithelial tears (27 patients; <1%) and intraocular pressure-related events (12 patients; <0.3%). There was a low annual incidence of stroke across all registries (0.0-0.5%).

Through two years, there was no difference between bevacizumab and ranibizumab in rates of death, myocardial infarction or stroke (APTC events), noted Daniel F Martin, CATT Study chair, in a keynote lecture at the 2013 Retina Day meeting ahead of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists’ annual congress in Liverpool.

Diagnosis and follow-up recommendations

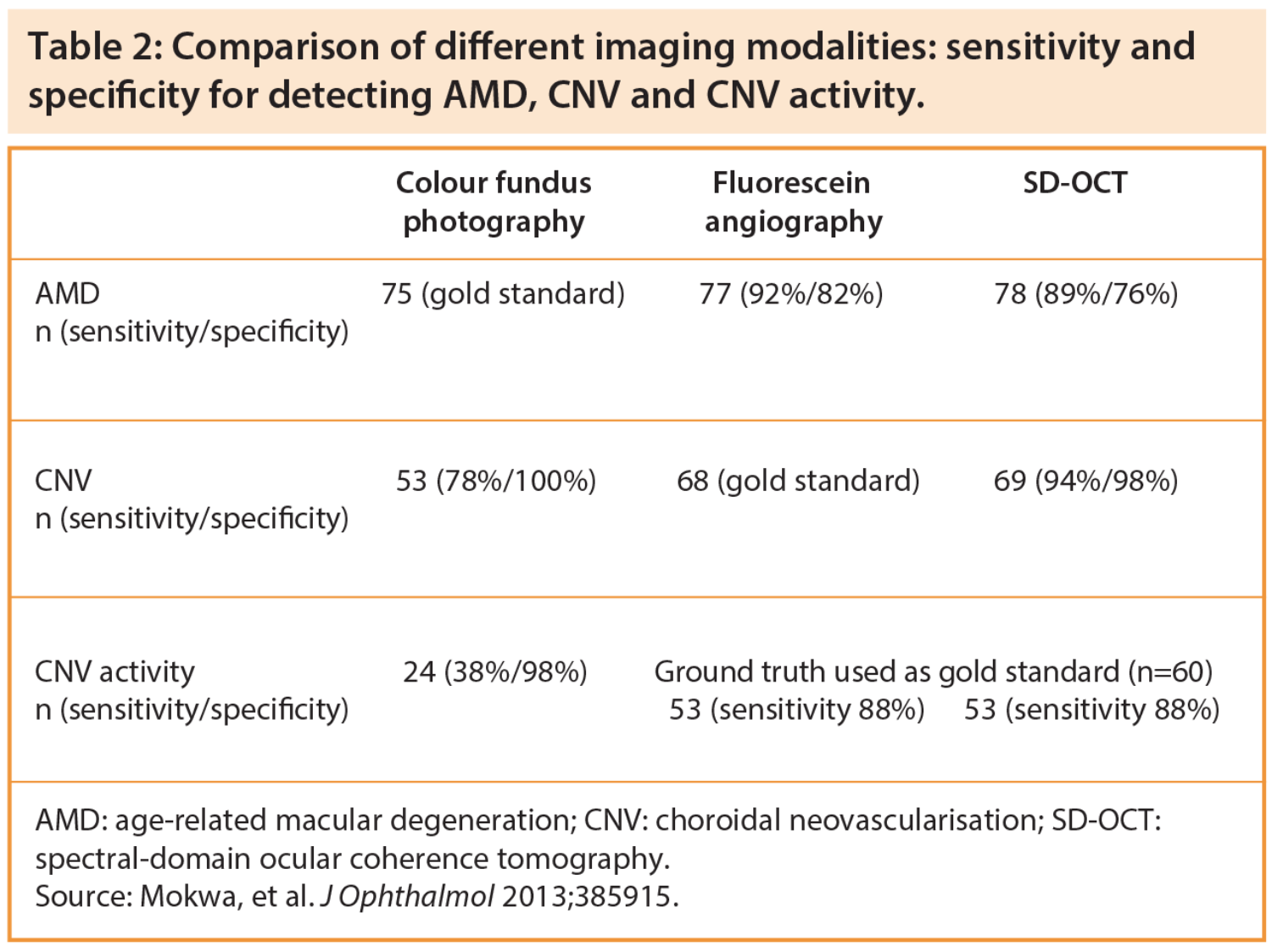

Imaging assessment using fluorescein angiography (FA) is mandatory for the primary diagnosis of neovascular AMD, when not contraindicated. It is also advisable in cases of unexplained vision loss or no morphologic response. Fluorescein angiography is also useful to help exclude retinal angiomatous proliferation (RAP) and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV) lesions. Indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) helps in diagnosing RAP and in documenting the stage of the neovascularisation process; it reveals the focal area of intense hyperfluorescence within the retina, arising from the deep capillary plexus forming the initial angiomatous lesion, which later on will form anastomosis with the choroidal circulation [9].

Non-invasive diagnostic assessment of the physiologic macula using OCT provides diagnosis of exudative macular degeneration, and allows for comprehensive follow-up before and after therapy. Spectral-domain OCT is increasingly used in clinical practice for the diagnosis and follow-up of AMD patients undergoing anti-VEGF therapy. Ocular coherence tomography is considered an excellent tool for screening and provides reliable monitoring during follow-up. Morphologic changes precede visual loss. Imaging using OCT provides measures of retinal thickening, which is responsible for part of visual acuity changes, and can show retinal cell loss, which causes irreversible visual loss.

Mokwa and colleagues compared colour fundus photography, FA and SD-OCT for the detection of AMD, CNV and CNV activity in a study involving 120 eyes of 66 AMD and control patients (Table 2) [8]. Investigators found that CNV lesions and activity may be missed by photography alone, but is of use in identifying drusen and pigmentary changes. SD-OCT was found to be highly sensitive for the detection of AMD, CNV and CNV activity, but cannot fully replace FA in the management of patients with CNV. Fluorescein angiography presented high sensitivity and specificity as a diagnostic tool for AMD and CNV if compared to SD-OCT. Both FA and SD-OCT revealed equal sensitivity to detect CNV activity, while colour fundus photography was high specific but non sensitive (Table 2).

In another study involving treatment-naïve eyes with nAMD, investigators found that atrophy of the outer retina is an important correlate for lower visual acuity in nAMD [10]. Quantitative analysis of SD-OCT retinal parameters revealed correlations between visual acuity and retinal and subretinal morphological changes in nAMD. Decreased VA after one year correlated with decreased volume of the photoreceptor layer (R=0.4, p<0.05). In the SEVEN-UP study, evaluating seven-year outcomes in ranibizumab-treated patients, macular atrophy was detected by fundus autofluorescence in 98% of eyes, with a mean area of 9.4mm2, and the area of atrophy correlated significantly with poor visual outcome (p<0.0001).

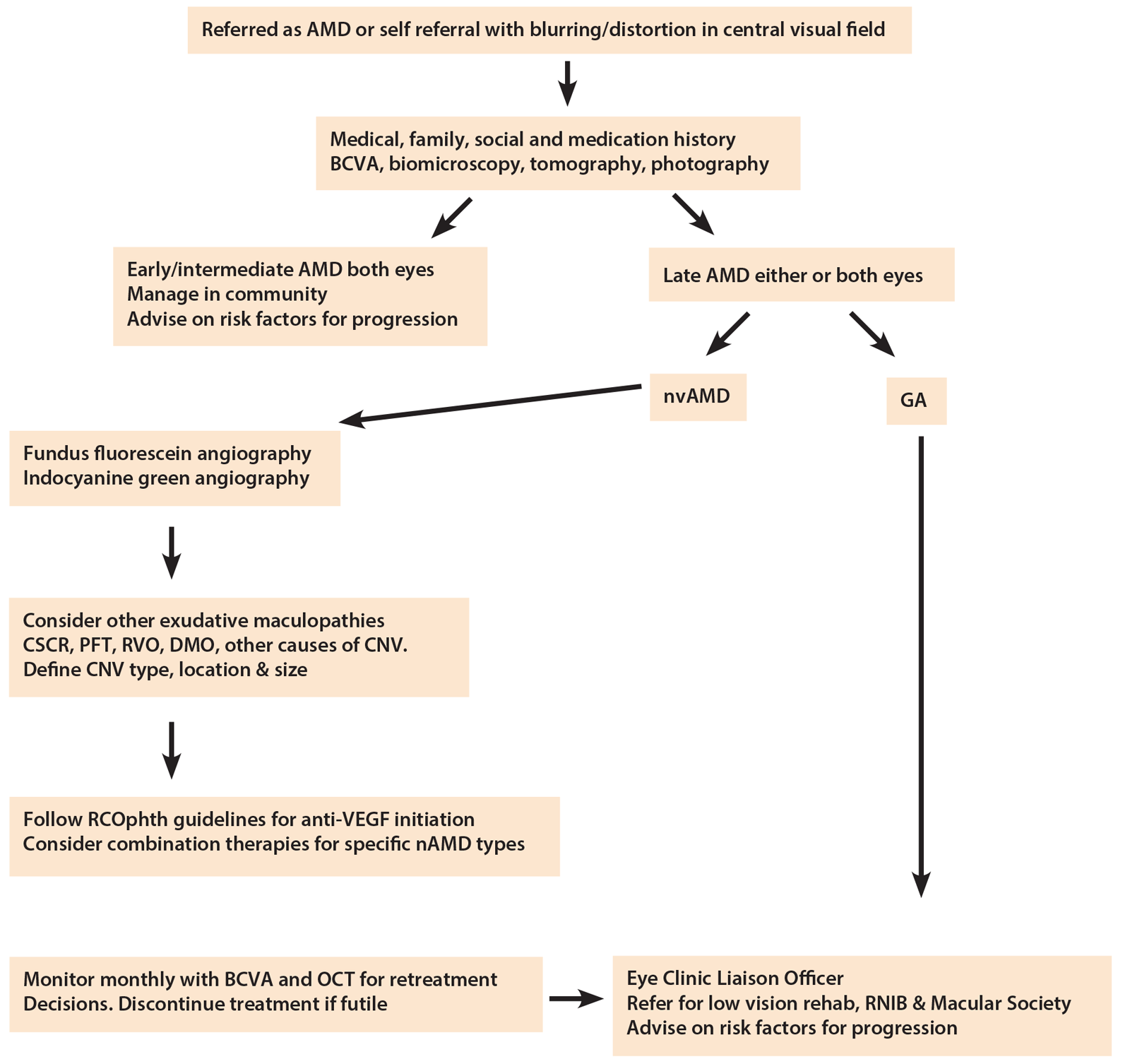

Figure 1: RCOphth AMD Guidelines 2013 - Management algorithm for age-related macular degeneration.

Key: OCT = optical coherence tomography. AMD = age-related macular degeneration. nvAMD = neovascular age-related macular degeneration (‘wet AMD’). GA = geographic atrophy (‘dry AMD’). CSCR = central serous chorioretinopathy. PFT = perifoveal telangiectasia. RVO = retinal vein occlusion. DMO = diabetic macular oedema. CNV = choroidal neovascularisation. VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor. RCO = Royal College of Ophthalmologists.

New guidelines on treatment delivery in the UK’s NHS

The Royal College of Ophthalmologists also issued in September 2013 updated guidelines for the management of age-related macular degeneration, intended to set the standards of best practice in the UK’s National Health Service and in the private sector (Figure 1) [11]. These include practical ABC recommendations on diagnosis, treatment and treatment delivery for neovascular AMD, outlined below:

a) Baseline investigations to ensure a definitive diagnosis of CNV should include BCVA, FFA and OCT:

- Stereoscopic fluorescein angiography is indicated to determine the extent, type, size and location of CNV.

- Indocyanine green angiography is useful when assessing patients with macular haemorrhage or suspected of having retinal angiomatous proliferative lesions,idiopathic polypoidal choroidopathy,or non-vascularised vs. vascularised pigment epithelial detachments.

- High resolution OCT is mandatory for diagnosis and monitoring response to therapy.

b) The treatment aim is the improvement or stabilisation of visual symptoms; the treatment recommendations should be guided by patient characteristics, type of lesion and logistics:

- Any potential role of triamcinolone as an adjunct to anti-VEGF therapy has yet to be established.

- Submacular surgery, macular translocation or radiation monotherapy are not recommended for the management of nAMD.

- In terms of anti-angiogenic therapy, ranibizumab and aflibercept can be used to treat all subfoveal CNV. Bevacizumab has similar functional efficacy as ranibizumab but it is unlicensed for intraocular use, andits ‘off-label’ status in this context should be clearly stated prior to its use in patients.

- The role of combination treatments is not yet established but photodynamic therapy (PDT) and radiotherapy continue to be investigated.

- All lesion types of nAMD benefit from treatment with licensed anti-VEGF therapy.

- Idiopathic PCV lesions respond best to PDT monotherapy or in combination with intravitreal anti-VEGF injections.

c) To ensure maximum benefit, treatment must be undertaken without delay and preferably within two weeks of initial development of symptoms or detection of a treatable lesion:

- Patients should be advised of the need for frequent monitoring when commencing a course of intravitreal drug treatment for AMD, typically every four to eight weeks depending on the licensed anti-VEGF drug used. Treatment and follow-up may need to becontinued for up to and beyond two years.

- Licensed anti-VEGF treatment will only improve vision in a third of patients, the majority will maintain vision and some 10% will not respond to therapy.

- It remains unknown whether less frequent dosing of ranibizumab or aflibercept than that used in the pivotal clinical trials will achieve the same visual benefit.

- Evidence suggests aflibercept treatment outcomes are similar to those of ranibizumab.

Challenges and emerging new approaches

Present challenges in the treatment of nAMD include identification of predictive biomarkers, establishing optimal treatment duration, dosing strategies and combination approaches, and clarifying mechanisms of inherent resistance or vision loss despite anti-VEGF therapy. Efforts to improve outcomes and overall treatment response continue.

The role of VEGF is well-established in pathologic vascularisation, including ocular neovascularisation. However, chronic VEGF neutralisation may lead to unanticipated side-effects and anti-VEGF therapies should thus be administered with caution.

Emerging new therapies under investigation as treatments for nAMD include mRNA or tyrosine kinase receptor inhibitors, as well as complement and integrin inhibitors. New modes of drug delivery, including sustained release solutions, are also under clinical evaluation. Experts comment that strategies to stop retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) loss appear to be as important in nAMD as in geographic atrophy.

References

1. Bloch SB, Larsen M, Munch IC. Incidence of legal blindness from age-related macular degeneration in Denmark: year 2000 to 2010. Am J Ophthalmol 2012;153(2):209-13.

2. Cohen SY, Mimoun G, Oubraham H, et al; LUMIERE Study Group. Changes in visual acuity in patients with wet age-related macular degeneration treated with intravitreal ranibizumab in daily clinical practice: the LUMIERE study. Retina 2013;33(3):474-81.

3. Schmidt-Erfurth U. The EURETINA guidance for the mangement of neovascular AMD. Main session 2: neovascular AMD. 13th EURETINA Congress, 26-29 September 2013.

4. Schmidt-Erfurth U, Kaiser PK, Korobelnik JF, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept injection for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: ninety-six-week results of the VIEW Studies. Ophthalmology 2013 Sep 28. [Epub ahead of print]

5. Rofagha S, Bhisitkul RB, Boyer DS, et al; SEVEN-UP Study Group. Seven-Year Outcomes in ranibizumab-treated patients in ANCHOR, MARINA, and HORIZON: a multicenter cohort study (SEVEN-UP). Ophthalmology 2013 May 3. [Epub ahead of print]

6. Awad M, Amoaku W, Yang Y, et al. Early visual response to ranibizumab in wet AMD may predict future treatment requirement – a post-hoc analysis of the EXCITE study. Poster presentation, 13th EURETINA Congress, Hamburg; 26-29 September 2013.

7. Holz FG, Bandello F, Gillies M, et al; LUMINOUS Steering Committee. Safety of ranibizumab in routine clinical practice: 1-year retrospective pooled analysis of four European neovascular AMD registries within the LUMINOUS programme. Br J Ophthalmol 2013;97(9):1161-7.

8. Yannuzzi LA, Negrão S, Iida T, et al. Retinal angiomatous proliferation in age–related macular degeneration. 2001. Retina 2012;32 Suppl 1:416-34.

9. Mokwa NF, Ristau T, Keane PA, et al. Grading of Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Comparison between Color Fundus Photography, Fluorescein Angiography, and Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography. J Ophthalmol 2013 May 8. [Epub ahead of print].

10. Ristau T, Keane PA, Walsh AC, et al. Relationship between Visual Acuity and Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography Retinal Parameters in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmologica 2013 Oct 2. [Epub ahead of print]

11. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Age-related macular degeneration: guidelines for management. September 2013. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists 2013.

TAKE HOME MESSAGE

-

Recent updated guidance recommendations from European retina specialists help consolidate current expert opinion on the management of neovascular AMD in clinical practice.

-

Baseline investigations to ensure a definitive diagnosis of CNV should include BCVA, FFA and OCT.

-

Anti-VEGF therapy is the first-line therapy in neovascular AMD.

-

Imaging using spectral-domain OCT is considered an excellent tool for screening and provides reliable monitoring during follow-up.

-

To ensure maximum benefit, treatment must be undertaken without delay and preferably within two weeks of initial development of symptoms or detection of a treatable lesion.

-

The treatment aim is the improvement or stabilisation of visual symptoms.

-

Treatment recommendations should be guided by patient characteristics, type of lesion and logistics.

-

Chronic VEGF neutralisation may lead to unanticipated side-effects.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME