Introduction

My first ophthalmology on-call was nine years ago and it was a fairly traumatic experience. I was an FY2 in a Welsh district general hospital and I was on my own – at least, that’s how it felt to me. Actually, I was the first rung in a three-tier ladder of emergency ophthalmology cover in the region. However, there was no sign of the other two rungs as I wandered up to the dingy eye room we occupied on the ENT ward.

At this point in time, my ophthalmic expertise extended to being able to check vision, use fluoresceine drops (but not check pressure), sometimes see cells in the anterior chamber and, on two previous occasions, successfully view the optic disc with a 78D lens. It took me several hours to stagger through four patients with relatively simple eye problems and I felt like a fraud. I remember phoning my second on-call hoping that he might attend and provide some desperately needed confirmation to my extremely shaky diagnoses, but to no avail. After leaving my shift hours late, I spent the forthcoming weekend catastrophising about hindsight diagnoses I had missed. Looking back, it is something of a miracle I wasn’t put off the specialty entirely.

The learning curve and the culture

I have since discovered my experience was not unusual. Many of my colleagues have tales of fear, uncertainty and isolation to accompany their early on-call experiences and there are, perhaps, a couple of factors influencing this.

First, ophthalmology is a discipline so specialist it comprises a knowledge base and skill set almost entirely absent from contemporary undergraduate medical training, with most medical schools providing only a week of experience. The outcome is that the majority of new doctors graduate with a threadbare understanding of how to assess a few eye problems and no real ability to manage any of them. Add two years of (usually) ophthalmology-free foundation training and you have a new ST1, ready to start their journey into the ocular.

Secondly, most eye services provide out-of-hours eyecare using the traditional model of non-residential on-calls. As such no one is expected to be on site after five unless there is an emergency to see. This can result in a very isolated and daunting novice experience, lacking the camaraderie and arms-length supervision of most acute inpatient specialties. Although in some large units trainees work shift patterns and there is always someone on site to ask, these tend to be the exception. Most new trainees cut their teeth on their own in a little room with an on-call consultant at home who they must pluck up the courage to call for advice. Combine this with a large dose of imposter syndrome and it is no surprise that new trainees look terrified as their first on-call duties approach. Yet the steep learning curve in ophthalmology is easy to forget once you have ascended it.

Bootcamp didactic talk.

The difficulty of inducting new trainees

In recent years, there has been an attempt to address this situation by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists (RCOphth). Following a 2017 College survey [1] about supervision and perceived safety levels in eye casualty and out of hours services around the country, the RCOphth Training Committee published two documents pertaining to the induction and supervision of new trainees [2,3]. The first is a recommended list of items that should be covered in the induction of a new trainee. Comprising 17 bullet points, it comprehensively covers the bulk of clinical ophthalmology. The second is a statement that all new trainees should receive early training in managing ocular emergencies and should be supernumerary for on-call and eye casualty services initially.

The General Medical Council (GMC) have made it clear that the traditional ‘sink or swim’ model is not acceptable [4,5], and eye departments face a huge challenge in reforming this previously widespread approach. So, how do we as a profession support our new trainees, flatten the learning curve and address that 17-point list on an annual basis, whilst maintaining a service?

There is relatively little published literature about this challenge. In 2019, the team at Manchester Royal Eye hospital designed a week-long crash course aimed at training up new ST1s in the relevant clinical skills to survive as fledgling ophthalmologists [6]. They reported great success with positive feedback from all participants and subjectively increased confidence levels going into clinical practice. A 2019 paper from the Scheie Eye Institute of Pennsylvania focussed on the benefits of a ‘buddy system’ to improve the confidence of new residents, but also reported that on-call bootcamps resulted in a significant improvement in the confidence of new trainees [7].

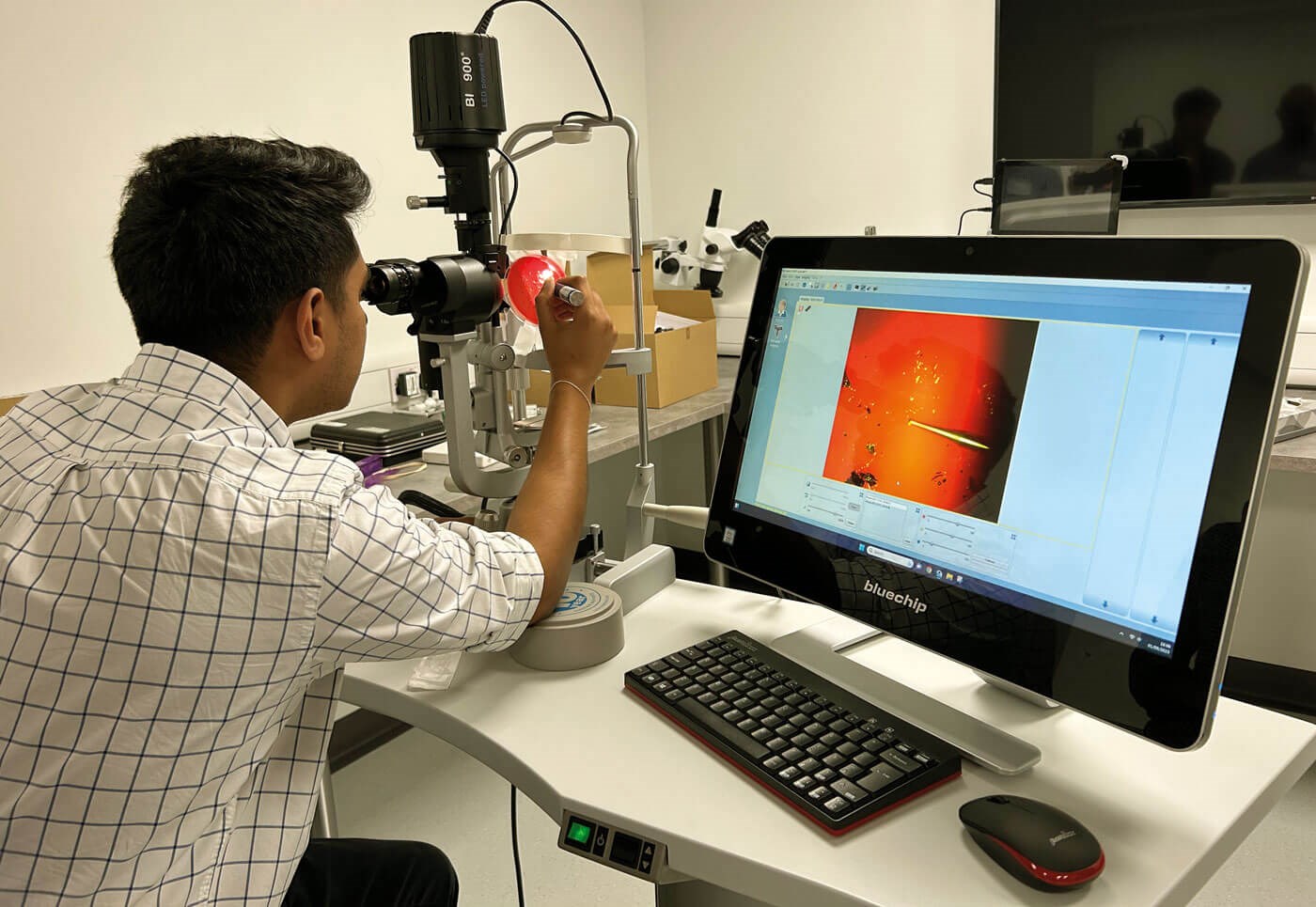

Slit-lamp skills station.

Small group scenario.

Creating a bootcamp

This year, across Scotland we received a bumper intake of ST1 trainees which brought this issue of induction into the foreground. With the remit of the College’s 17-point list, two days at the end of August and a large room with a screen and three slit-lamps, a few of us set out to create our own ophthalmology bootcamp.

What was included?

We wanted this course to be applicable to new ST1 trainees and other novices, such as GP trainees, who would be covering ophthalmology on-calls as part of their training. This required a course curriculum that assumed no prior experience or specialist knowledge. Therefore, we aimed to cover foundational basic sciences in clinically relevant anatomy, physiology and optics before progressing into ophthalmic history taking and all the various examination skills. Further talks covered adjunctive investigations such as OCT and ultrasound. Common acute presentations were divided into red eyes, vision loss and diplopia and were discussed in the context of triage, assessment and correct documentation. Skills included foreign body removal, corneal suture removal, corneal scraping and Goldmann tonometry.

What was the format?

Given that the list of subjects was long and included several fairly heavy topics, we worked to pare each topic down to a few essential learning objectives. Didactic lectures were limited to a maximum of 30 minutes per topic and were interspersed with small group interactive scenarios which built on the knowledge acquired from previous talks. These scenarios took the form of role-play activities between a ‘patient’ and an ‘examiner’ with a third person acting as observer. The ‘patient’ was provided with a script describing the symptoms and signs of disease that might commonly be seen on call. Different scenarios were rotated between the groups over 30 minutes with the participants regrouping at the end to debrief with the faculty members to ensure the learning objectives had been met.

With a broad range of topics to be covered in a short space of time, we were wary of learner fatigue. To ensure the most important learning objectives of the course were retained, we spiralled the course curriculum to ensure that key objectives were re-visited in subsequent sessions. For the skills sessions and slit-lamp tutorials, we used video slit-lamp microscopes to demonstrate correct technique and to allow for faculty to observe and critique learners.

What was needed?

We hosted nine delegates at ST1 / GPST1 level and to cater for the limited space in our department and to increase reproducibility, the course was designed to be conducted in one large room. Two full-time facilitators were aided by five other part-time facilitators who would support or teach certain sessions around their clinical commitments. The faculty were comprised of four consultants, one ST6 and two ST3s. However, the course could have been run with as few as three full-time facilitators for nine participants.

The set up for didactic talks and small group scenarios was very simple and only the seating needed to be re-arranged between sessions. The scenarios, complete with clinical photographs, had been designed in advance by the faculty and printouts were given to the delegates to lead them through these.

Three video slit-lamp microscopes were used for the slit-lamp and clinical skill’s sessions. The delegates were divided into groups of three, rotating through each skill station which was supervised by a faculty member. To simulate corneal suture removal, we purchased simulation eyes and placed multiple corneal sutures in advance of the session. Delegates were then given a short talk on correct technique and observed while they practised suture removal on the model. Corneal foreign body removal was simulated using agar plates, embedded with pieces of rust and dirt. Corneal scraping was simulated with grapes marked with permanent marker and mounted on sticks. Goldmann tonometry was practised on each other with the supervision of a facilitator. For these skills, delegates were given the opportunity to achieve a workplace-based assessment sign-off as a simulation if they were able to demonstrate the correct knowledge and technique.

What were the challenges?

Given the relatively short space of time in which to deliver the course, the main challenge involved compressing many bulky topics into short, bite-sized sessions and keeping those sessions to time on the day. With several talks being 10-15 minutes long, there was very little room for error and even a slight over-run could quickly build up to a significant delay later in the day.

Another difficulty was finding the appropriate date for the course. As this was a cross-deanery event, allowances had to be made for local inductions to take place in the first week of August. However, to be most effective, the course needed to happen before the new trainees joined the on-call rota. In the end, the last week of August was the only date that could accommodate faculty and departments across sites. This worked out well as the new trainees came to the course with enough experience in ophthalmology for them to appreciate the relevance of course content and were highly motivated to engage.

How was the course received?

We received excellent feedback from all participants. One hundred percent of participants rated the course 5/5 and all felt the course would change their practice going forward. Each session was scored individually and all sessions received an aggregate score of 4.78/5 or higher.

Following the success of the pilot we hope to expand the bootcamp to become Scotland-wide next August.

Conclusion

The steep learning curve for new ophthalmology trainees remains a legacy of scarce undergraduate teaching and limited foundation posts in our specialty. The RCOphth have recommended a thorough induction to ophthalmology for all new trainees. However, this can be extremely challenging for individual departments to arrange on an annual basis during changeover. We designed a two-day ST1 bootcamp to cover the key topics and skills required of a junior ophthalmologist on-call. Following a successful pilot of nine participants and having received excellent feedback, we aim to expand the reach of the course to the whole of Scotland, hopefully relieving the burden on individual departments.

References

1. King C, Tytko A, Spencer AF, Mead A. Royal College of Ophthalmologists: National Survey of ST1 Supervision. Eye 2019;33(6):866-7.

2. Recommended Induction for Ophthalmology (2017). The Royal College of Ophthalmologists.

https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/

uploads/2020/05/RCOphth-Guidance

-On-Induction-For-Ophthalmology.pdf

3. Acute Services Training (2017). The Royal College of Ophthalmologists.

https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/

wp-content/uploads/2020/05/

Acute-Services-Training-For-Website.pdf

4. The Trainee Doctor: Foundation and Specialty including GP Training (2011). The General Medical Council.

https://www.foundationprogramme.nhs.uk/

wp-content/uploads/2015/03/The_Trainee

_Doctor_1114.pdf_56439508.pdf

5. Leadership and management for all doctors (2012). The General Medical Council.

https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/

ethical-guidance-for-doctors/leadership

-and-management-for-all-doctors

6. Walkden A, Young JF, Spencer AF, Ashworth J. Determining the needs of ophthalmic trainees entering into specialist training and how they can be met. Adv Med Educ Pract 2019;10:201-6.

7. McCoskey M, Shafer B, Nti A, et al. First-Year Ophthalmology Residency Call Structure and Its Association with Resident Anxiety and Confidence. J Acad Ophthalmol 2019;11(1):e9–15.

[all links last accessed October 2023]

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME