Almost two million people in the UK suffer sight loss, a number forecast to double over coming decades. Major causes of blindness are age-related macular degeneration (AMD), glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, cataract and uncorrected refractive error. Prevalence of these sight-threatening conditions is rapidly increasing, in part due to the aging population, creating escalating demand for eye care and social care services (Table 1).

Hospital eye units, understaffed, overstretched and under resourced in many areas, are struggling to adequately meet demand. Resulting treatment delays can mean patients suffer avoidable sight loss. Prompt action is needed to resolve current and future capacity issues in a sustainable manner and also to smooth out unacceptable variation in eye care provision, say patient charities, consultant ophthalmologists and allied health care professionals.

Failing trusts

Responses from NHS trusts obtained under the Freedom of Information Act indicate that two thirds are failing to meet follow-up times for neovascular AMD, according to research by the Macular Society published in November 2013.

Of the 80 trusts that responded to questions from the Macular Society, 34% confirmed they are meeting the four week follow-up times for patients affected by neovascular AMD, as recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Many blamed a lack of resources to cope adequately with demand. Close to one third of trusts questioned had not yet implemented NICE guidance relating to the availability of aflibercept (Eylea) as a first-line treatment option for patients affected by neovascular AMD.

Some trusts had also not provided funding for NICE-approved treatments to be made available for two other sight-threatening conditions. Of those surveyed, 26% have not made recommended treatments available for diabetic macular oedema and 34% have failed to make treatments available for retinal vein occlusion.

“It is unacceptable that two thirds of NHS trusts are failing patients in this way,” said Helen Jackman, Chief Executive of the Macular Society. “Many will have inevitably experienced unnecessary and irreversible sight loss due to the delays in introducing new treatments and follow-up times.”

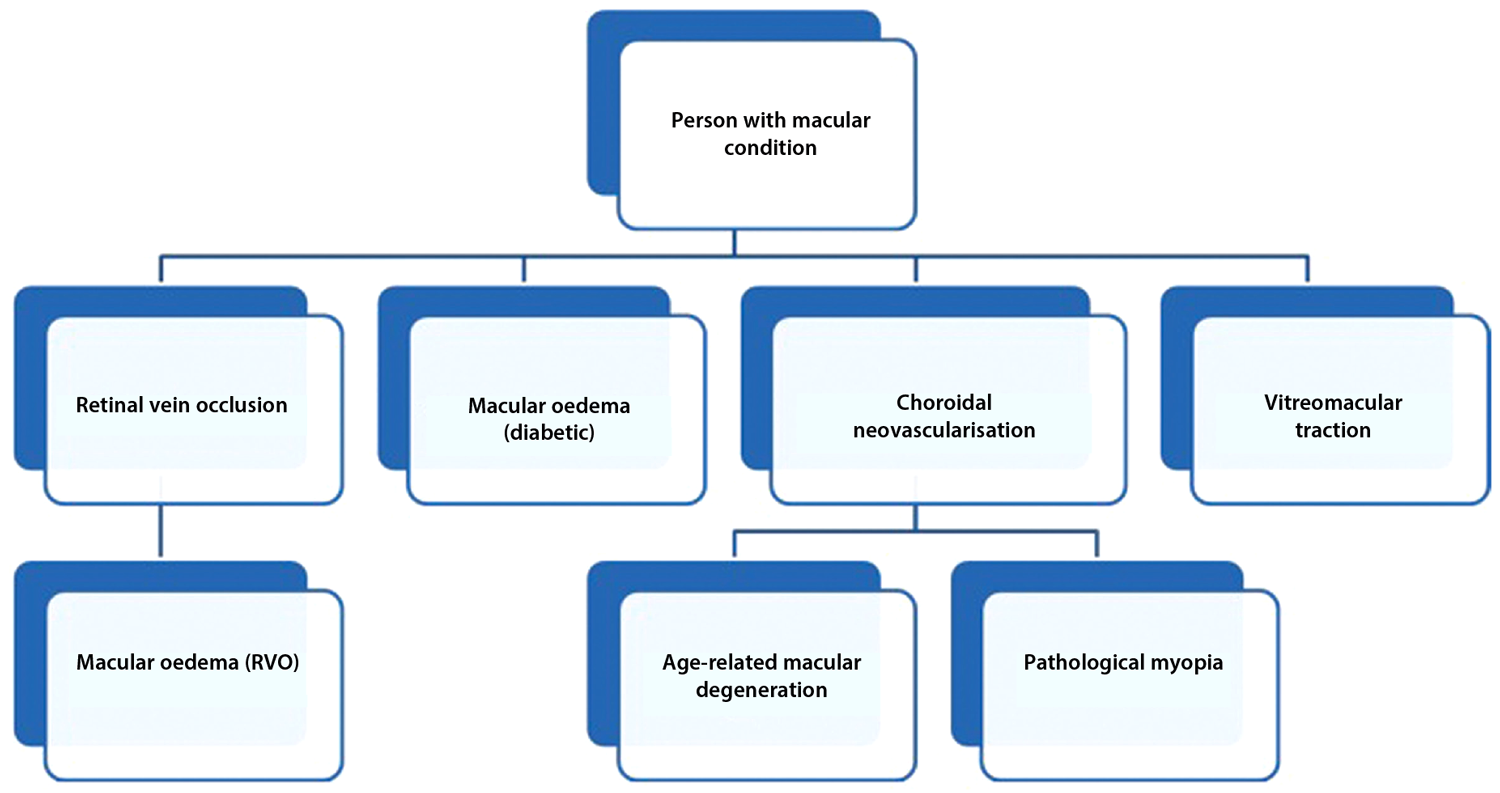

Clinical commissioning groups (CCGs), NHS England and local authorities are required to support rapid implementation of NICE guidance – within three months of publication – to ensure that approved treatment options are available for use in the NHS. Figure 1 and Table 2 detail recent developments in the NICE pathway for macular conditions. Modern stereotactic radiotherapy, shown to reduce regression of new blood vessels, has been developed as an outpatient treatment for selected patients with neovascular AMD, and may decrease the need for retreatment using intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy.

Figure 1: NICE eye conditions pathway: macular conditions.

Table 2: Related NICE guidance issued for macular conditions

TA155

Issue date August 2008,last modified May 2012

Recommendation

Ranibizumab recommended as an option for the treatment of neovascular AMD, if: BCVA is between 6/12 and 6/96; there is no permanent structural damage to the central fovea; lesion size is ≤12 disc areas in greatest linear dimension; and there is evidence of recent presumed disease progression (e.g. blood vessel growth or recent VA changes).

Condition nAMD

TA229

Issue date July 2011

Recommendation

Dexamethasone intravitreal implant recommended for the treatment of macular oedema secondary to retinal vein occlusion.

Condition MO (RVO)

TA274

Issue date April 2013

Recommendation

Ranibizumab recommended as an option for treating visual impairment due to diabetic macula oedema only if the eye has a central retinal thickness of ≥ 400µm at the start of treatment.

Condition DMO

TA283

Issue date May 2013

Recommendation

Ranibizumab recommended as a possible treatment option for visual impairment caused by macular oedema secondary to retinal vein occlusion.

Condition MO (RVO)

TA294

Issue date July 2013

Recommendation

Aflibercept injection recommended as a possible treatment for some people with neovascular AMD.

Condition nAMD

TA297

Issue date October 2013

Recommendation

Ocriplasmin intravitreal injection recommended as an option for treating vitreomacular traction, including when associated with a macular hole ≤400µm and / or severe symptoms.

Condition VMT

TA298

Issue date November 2013

Recommendation

Ranibizumab recommended as an option for treating visual impairment due to CNV secondary to pathological myopia.

Condition CNV/pMyopia

TA301

Issue date November 2013

Recommendation

Fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implants recommended for people with chronic diabetic macular oedema, provided that they are pseudophakic and have persistent DMO which has been chronic despite prior therapy.

Condition DMO

‘Saving money, losing sight’ survey reinforces serious shortcomings

Further alarming results from a recent Royal National Institute for the Blind (RNIB) survey conducted in August 2013 suggest that patients are going blind unnecessarily because of severe capacity problems in eye clinics across England [1,2]. Issues raised include:

- Concerns raised by patients about aspects of their care, including cancelled and delayed appointments, over-subscribed clinics, long waits to see a professional at each appointment and rushed consultations.

- Hospital managers are all too often ignoring the capacity crisis.

- Commissioners, who plan and fund health care services locally, are not always working with accurate information on the eye care needs of their local populations.

Drivers of capacity constraints

The RNIB surveyed staff in eye clinics across England about current and future capacity. By September 2013, 172 responses were received from a range of eye health professionals including 91 ophthalmologists and 59 ophthalmic nurses.

Survey results reveal sizeable capacity problems in ophthalmology clinics across England: 37% of respondents said that patients are ‘sometimes’ losing their sight unnecessarily due to delayed treatment and monitoring caused by capacity problems. The capacity crisis is countrywide, with clinics under extreme pressure to meet demand.

Four main drivers contribute to this lack of capacity, according to RNIB’s survey: a significant increase in demand across a range of conditions, particularly macular eye diseases; no clear strategy for coping with current and future demand; a lack of local planning of eye health and sight loss services; and an inconsistent approach to commissioning eye care services. One quarter of all commissioning groups have no lead for eye care, with poor dialogue between CCGs and ophthalmology specialists hampering commissioners’ ability to plan and deliver high quality eye care.

RNIB recommendations

RNIB states that urgent action is needed to ensure effective and efficient eye care services are in place to meet rising demand, identifying six recommendations:

- NHS England must undertake an urgent inquiry into the quality of care in ophthalmology.

- National leadership is put in place to address unacceptable variation in eye care provision.

- Hospital managers and staff must work together to identify and address capacity problems in their eye clinics.

- CCGs must properly assess and adequately fund eye clinics so they can meet rising demand for services.

- NICE must prioritise the production of its eye health clinical guidelines and Quality Standards.

- Eye Clinic Liaison Officers must be an integral part of the patient pathway.

Ophthalmology had the second highest number of outpatient attendances of any speciality in 2011/12, accounting for 8.9% of all outpatient appointments (6.8 million). For the same period, there were 620,000 finished inpatient consultant episodes related to ophthalmology, the majority carried out as day cases.

Some 81% of respondents said capacity is insufficient to meet current demand, and 51% said extra evening and weekend clinics were undertaken to meet demand. Some 94% reported that future capacity will not meet rising demand, with just 5.2% saying that there is enough capacity to adequately meet current and expected future demand.

Increased financial investment, additional clinic space and better IT clinical management systems were identified as measures necessary to increase capacity in ophthalmology clinics. Other initiatives include greater involvement by trained optometrists and nurses in undertaking clinic assessments and evaluation of images, administration of intravitreal injections, as well as recruitment of more consultants or middle grade ophthalmic medical staff.

Clinical need, not money, must shape service provision in eye clinics, say ophthalmologists

Increasing patient demand for intravitreal injections for treatment of AMD, other macular diseases and diabetic eye conditions appears to be the main catalyst for current capacity woes in many eye clinics. In some eye departments struggling to meet demand, efforts to maintain the AMD treatment schedules have resulted in serious delays in the assessment and treatment of patients with diabetic retinopathy.

Across ophthalmic services, overbooked clinics and a backlog of patients continues to hamper prompt assessment of patients with chronic eye conditions such as glaucoma, who often face rescheduled or cancelled appointments. Commissioners are also rationing cataract surgery to balance the books, while demand for low vision services has dramatically increased.

“The Hospital Eye Service does face a capacity issue, due to a recurrent backlog of patients requiring ongoing ophthalmic follow-up, but it is being controlled and managed, albeit under pressure,” commented Harminder Dua, President of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists and Professor and Honorary Consultant Ophthalmologist, Queens Medical Centre, Nottingham, UK, in a telephone interview with the author.

“Initiatives include virtual clinics, as well as earlier discharge of stable patients to community-based networks that involve general practitioners and optometrists. Properly managed, community ophthalmology initiatives can cut follow-up patient waiting lists in hospital eye clinics by up to one third.” (See section on commissioning better eye care below)

Commissioning better eye care

New guidance issued jointly by the College of Optometrists and the Royal College of Ophthalmologists outlines recommendations designed to improve the quality and efficiency of eye health services in three key areas: urgent eye care, AMD and low vision. The guidance, developed with input from clinicians, commissioners, GPs and patient groups, is designed to be of assistance to Clinical Commissioning Groups and other Local Professional Networks for Eye Health ‘as they work together to prevent avoidable sight loss’.

The new guidance shows how commissioning community services delivering urgent eye care can reduce the number of people attending hospital casualty services at a time when they are struggling to meet demand. The College also published recommendations for glaucoma services in February 2013. Recommendations to improve services for diabetic retinopathy and oculoplastics are expected soon.

AMD guidance

To minimise avoidable treatment delays, patients presenting to community optometrists with suspected wet AMD should be referred directly and urgently to a specialist macular clinic where imaging and treatment facilities are available. Electronic referrals should be introduced to improve the speed and quality of referrals.

As the colleges note, the key objective for an AMD service is to prevent or minimise sight loss. Outcomes for patients treated with ranibizumab will be best when they are seen and treated within two weeks of diagnosis and receive follow-up appointments at four-weekly intervals. Commissioners are urged to work with managers and clinicians to ensure that their services have rapid access and the capacity to meet demand in a timely manner now and in the future.

The view of the College is that, where circumstances and facilities allow, administration of anti-VEGF agents by intravitreal injection should be given by a specialist doctor trained in the procedure. Additionally, it is reasonable for non-medical health care professionals to administer anti-VEGF agents subject to certain stipulations, including consultant oversight, immediate availability of an ophthalmic specialist doctor to manage any complications and continuous audit of the injection service.

Urgent eye care

The incidence of presentations to eye casualty services has been estimated at 20-30 per 1,000 per year. Most hospital urgent eye care services report that they struggle to keep pace with demand and that a significant proportion of patients seen in these services have conditions which could be diagnosed and managed in a primary care setting by optometrists.

Joint guidance recommends minimising visual loss from sight-threatening conditions, particularly trauma, through prompt triage, diagnosis and treatment. Those diagnosing urgent eye conditions should have a slit-lamp and the necessary skills to use it. Commissioners should ensure that there is adequate availability of urgent (same day or next day) appointments in the primary care service and educate the public and referring clinicians to use them as the first port of call for urgent eye conditions to achieve a significant shift of urgent eye care from hospital to primary care settings.

Low vision services: an integral part of the eye care patient pathway and ophthalmology team

The main aim of low vision services is to enable people with loss of vision to regain or maintain as much independence and autonomy as possible. Low vision services achieve this through tailored individual tools, including rehabilitation, visual aids, emotional support and advice. Study data suggest an underprovision of emotional support and family support for visually impaired patients in the UK [3].

Access to low vision services should be prompt and flexible, as early intervention is key to securing the best outcomes. Serious consideration should be given to the provision of an eye care liaison officer (ECLO) in every eye clinic in order to facilitate this. Currently, 56% of eye clinics in England do not have ECLO support in place. Commissioners are urged to ensure low vision services have dedicated funding in their programme budget for eye health and to explore the possibility to jointly fund and provide the service with health, local authority and voluntary sector resources.

Regional variations in service provision often arise due to different approaches adopted at trust level, such as arbitrary visual acuity thresholds for provision of cataract surgery, used to restrict cataract services due to financial constraints. The effect of cataract on visual quality cannot be measured by number of lines read by the patient on an eye-test chart. Glare, haloes, star-burst and reading and driving difficulties can be present in eyes with cataract even though vision is ‘normal’ (6/6) on the eye test.

Clinicians take a different view to decide whether or not a patient should have cataract surgery. Three simple questions provide the answer: Does the patient have symptoms attributable to cataract? Does the patient need and want cataract surgery? And, having understood the risks involved, does the patient still want it? If the answers are yes, then cataract surgery should be made available.

“Trusts are also under pressure to treat ‘new patients’, which means that follow-up patients tend to be pushed back and suffer delayed or cancelled follow-up appointments,” explained Prof Dua. “A key challenge is to mitigate the risk of avoidable sight loss amongst patients on follow-up waiting lists, for example in those with diabetic retinopathy.

“The message to clinical commissioning groups and hospital managers is that clinical need and not money should drive decisions,” Prof Dua added. “Clinical need and patient choice are fundamental principles in governing eye health service standards. If you put the patient first, everything tends to fall into place.”

Joined-up thinking recommended

“It is tempting to look at capacity issues in isolation at a subspecialty service level, particularly where there is actual or impending failure to meet access targets or treatment protocols,” commented Richard Smith, Consultant Ophthalmologist, Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust. “However, this can result in a short-term improvement at the expense of another part of the service.

“Commissioners and providers will need to work together more closely to achieve a more proactive approach to capacity planning in eye care,” Mr Smith added. “There is a danger that the increasing tendency for commissioners to put eye care services out to tender may make coherent capacity planning more difficult, but I hope that as Local Professional Networks for Eye Health become established, they will take on this role.”

Use population data and electronic patient record systems to plan ahead

Existing population data (stratified by age and adjusted for ethnic mix) may be used to predict the numbers of people in each area of the country who will have the conditions that account for the bulk of the workload of the hospital eye service, one year, five years and 10 years from now. Electronic clinical record systems, where in use, allow fine-tuning of these estimates, by comparing observed versus expected prevalences for the major eye conditions.

These estimates can then be translated into projections for the numbers of consultations, surgeries, intravitreal injections, visual field tests and retinal images likely to be required, now and at various points in the future. Projections may then be made about the necessary workforce and physical facilities needed to deliver this capacity.

Electronic medical record systems that incorporate clinical data management software, including integrated image and test management results, further enhance practice efficiency, providing seamless access to all patient data for improved productivity.

Challenge complacency

Commissioners argue that they don’t get a chance to speak to front-line staff in specialist areas such as ophthalmology. Eye doctors cite a squeeze on funding and that identified investment needs often go unheeded.

“Our service is managed well,” confided another consultant ophthalmologist. “However, we have a clear need for a 30% service expansion and have done for at least three years, but while this has been talked about at length, investment has not materialised. We need more investment for on call support, wet AMD support and surgical waiting list support. We have also been asked not to apply for any more study leave funding for the next year.”

A recognised issue at present is that ophthalmologists and the commissioners who buy ophthalmology services tend to approach capacity problems reactively and in isolation. While advances in technology and therapy periodically throw wildcards into the mix, particularly where they provide effective treatment for a condition previously untreatable, much can be done through closer and regular dialogue on capacity provision. Ophthalmologists suggest regular liaison between clinicians and CCG representatives regarding ophthalmology and early implementation of NICE technology appraisal guidance, at least twice yearly, to ensure enough capacity to deliver necessary ophthalmic services.

Invited to comment on capacity issues in eye clinics, a spokesperson for a leading NHS Commissioning Support Unit replied, “Unfortunately, the key specialists in our CCGs aren’t available. However, I understand that they are working on this area with a view to planning new developments, and there should be a good story to tell in a few months’ time.”

There’s a general blanket ban in the NHS on carrying out minor cosmetic procedures to eyelids. Those who can afford private care can seek redress in the private sector. Those who cannot have to learn to live with their lumps and bumps.

References

1. RNIB. Saving money, losing sight. RNIB Campaign Report. RNIB November 2013.

2. Hives-Wood S. Patients are losing sight because of rising demand in eye clinics. BMJ 2013;347:f6877.

3. Gillespie-Gallery H, Conway ML, Subramanian A. Are rehabilitation services for patients in UK eye clinics adequate? A survey of eye care professionals. Eye (Lond) 2012;26(10):1302-9.

TAKE HOME MESSAGE

-

Patients are suffering because of severe capacity problems in eye clinics across England.

-

Increased financial investment, additional clinic space and better IT clinical management systems have been identified as measures necessary to increase capacity in ophthalmology clinics.

-

Further initiatives to extend capacity include virtual clinics and earlier discharge of stable patients to community-based networks that involve general practitioners and optometrists.

-

The message to clinical commissioning groups and hospital managers is that clinical need and not money should drive decisions.

-

Existing population data may be used to predict the numbers of people in each area of the country who will have the conditions that account for the bulk of the workload of the hospital eye service, one year and 10 years from now.

-

Commissioners and providers need to work together more closely to achieve a more proactive approach to capacity planning in eye care.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME