The author looks at the career of William Mackenzie and the important role he played in establishing the status of ophthalmology as a recognised medical speciality.

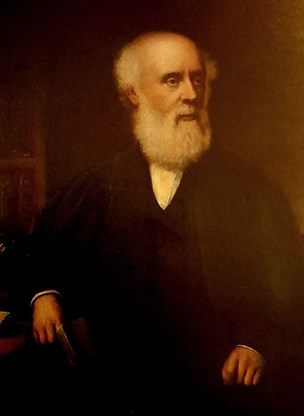

There are certain individuals who, blessed with ability and means, are destined to leave the world a better place than it was before their presence. Occasionally, these people go further and their efforts and intellect benefit not only their peers and contemporaries but also future generations. Such a person was undoubtedly William Mackenzie (Figure 1). A renowned ophthalmologist and polymath, his altruistic career established a respected medical institution and earned him a revered place in the history of his profession and in the story of his native city of Glasgow.

Figure 1: Portrait of William Mackenzie. Image provided courtesy of the

Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow (ref 96).

William Mackenzie was born on 29 April 1791 in the parish of Glasgow. The second child and only son of James Mackenzie, a successful muslin manufacturer. The family resided in a substantial villa in the then fashionable residential area of Queen Street [1].

The university years

James Mackenzie appears to have been a devoutly religious man and had aspirations that his son should pursue a career as a Minister of the Church of Scotland. To this end, William Mackenzie was enrolled at the Glasgow Grammar School. The Scottish education system prided itself on bestowing a broad curriculum upon its pupils and Mackenzie proved to be an exemplary ‘Lad o’ Pairts’ i.e., an intellectually gifted all-rounder who was also fluent in French and German. Mackenzie went on to leave school at the somewhat early age of 12 and was subsequently matriculated in the Faculty of Arts of Glasgow University, this being the traditional educational route for entrance to divinity, and hence the ministry.

However, there is no record of him graduating with a Master of Arts degree [2]. Instead, the young Mackenzie was to demonstrate a remarkable spirit of independence and in 1810, at the age of 19, enrolled in the Faculty of Medicine [3]. Mackenzie had become fascinated by the sciences and such leanings had lead to doubts and challenges regarding certain biblical assumptions, in particular the story of the creation [3]. This dramatic change in career intentions must have caused some consternation, however, theology’s loss was to be medicine’s gain.

“With many of its citizens having taken part in the Napoleonic Wars it was soon evident that Glasgow urgently required a specialist eye hospital”

Throughout his medical career, Mackenzie was to prove fortunate in the expert training he received. This pattern was established early on when between 1813 and 1815, as a junior doctor, he practised under the tutelage of Dr Richard Millar at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary [1]. The latter went on to be appointed the first Regius Professor of Materia Medica at Glasgow University in 1831. This early training was to inculcate Mackenzie with an enthusiasm for general practice, which never left him even when he became a distinguished ophthalmologist. In 1815, Mackenzie successfully obtained the Diploma of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow, the first of many honours to be bestowed upon him. Most importantly Mackenzie was beginning his medical career on a very sound academic basis.

1815 was to prove to be a seminal year for William Mackenzie.

Interest in ophthalmology

Whilst still a student, Mackenzie had become interested in the study of the structure, function and diseases of the eye. This may have seemed a somewhat unpromising branch of medicine to enter. In the early 19th century ophthalmology was in its infancy and had yet to be subjected to rigorous scientific analysis. Unqualified practitioners were still to be found and it was not necessarily always considered respectable to practice as an ophthalmologist [1]. Furthermore, for many years the medical establishment had resisted attempts by practitioners to specialise in particular branches of medicine, believing that specialisation could be viewed as a form of advertisement, luring patients away from their general practitioner [4]. Unfortunately, ophthalmology in particular lagged behind organised attempts to raise standards. Perhaps Mackenzie realised that the nascent world of ophthalmology was a branch of medicine that could particularly benefit from his formidable intellect and skills.

The question would be how best to obtain appropriate quality tuition and experience.

At this time, it was often the case that scions of well-to-do families would undertake a tour of European cities and academic establishments in order to improve their knowledge and skills. Thus, with adequate financial provision from his family, in 1815, Mackenzie departed for a three-year tour taking in London and then France, Germany, Austria and Italy [4].

Whilst visiting Vienna in 1817, Mackenzie came under the influence of leading Ophthalmologist Georg Joseph Beer. In a remarkable coincidence, the latter had also initially studied theology and later switched to medicine. In 1812 Beer had been appointed to the Chair in Ophthalmology at University of Vienna. Professor Beer was regarded as an outstanding clinician, surgeon, teacher and author. Undoubtedly Mackenzie would have benefited enormously from his stay.

And hence, in 1818, his ‘grand tour’ completed, Mackenzie returned to Britain with renewed determination to practice ophthalmology.

Early medical career

Whilst in later years Mackenzie was to achieve the highest successes in his chosen field, his early years in the medical profession were to produce their fair share of disappointments and tribulations.Initially taking up residency in Newman Street, London, Mackenzie became a member of the Royal College of Surgeons of England [1]. He attempted to set up a general practice with particular emphasis on treating disorders of the eye. However, this venture appears to have met with only limited success. More disappointment was to follow when an application to take up a lectureship in anatomy in London University was turned down. This must have felt particularly annoying since Mackenzie had just written a textbook on the lacrimal organs of the eye [1].

Understandably somewhat discouraged, in 1819 Mackenzie decided to return to his native Glasgow. This decision was to mark the successful turning point of his career.

Within months of his arrival Mackenzie became a Fellow of the Faculty of Physicians of Glasgow [3]. Soon the academic world beckoned and he was appointed Professor of Anatomy and Surgery at Anderson’s College Medical School, establishing a curriculum including the anatomy, surgery and diseases of the eye [1]. Mackenzie also wasted no time in establishing a thriving general practice.

The fruits of the industrial revolution and, in particular, the invention of the steam engine were to result in dramatic and profound changes to Glasgow. The city rapidly grew from a small university and cathedral town into a densely populated industrial metropolis. This alone would have necessitated improved eyecare, however, external events were soon to make this need even more pressing.

From 1803 troops started returning having fought in the Napoleonic wars. Those returning from Egypt were frequently inflicted with the sight-threatening disease of trachoma. This brought about an upsurge in interest in ophthalmology. Soon specialist eye hospitals were being established up and down the country [1]. A notable early example being that of London’s Moorfields Eye Hospital in 1804. With many of its citizens having taken part in the Napoleonic Wars it was soon evident that Glasgow urgently required a specialist eye hospital.

At the age of 32, William Mackenzie rose to the task with alacrity. Shrewdly he quickly enlisted the help and enthusiasm of Glasgow’s leading Ophthalmologist Dr George Cunningham Monteath, along with the city’s Member of Parliament Henry Monteath (no relation) and the Lord Provost William Smith, Esquire. These were three influential people who were impressively well connected. Before long, meticulous planning meant that a management committee had been formed, public subscriptions had been collected and a suitable premises had been procured.

Thus, on 7 June 1824 eyecare and the treatment of eye diseases took a significant step forward in Glasgow with the opening of a dedicated Eye Infirmary, located in a small house at 19 Inkle Factory Lane, North Albion Street [1]. Like most important buildings of that era, it was in close proximity to Glasgow Cathedral. The institution was to have a distinguished and successful future. As patient numbers rapidly increased and facilities required expansion, the infirmary occupied three further sites before finally being housed in Gartnavel General Hospital.

International renown

As though founding an eye hospital was not enough, William Mackenzie was soon to make another remarkable contribution to ophthalmology. In 1830 he published his ground-breaking textbook Practical Treatise on Disease of the Eye with Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown & Green of London [4]. Covering some 853 pages the text was immediately rapturously acclaimed by the medical press and it became for some time the standard reference work in ophthalmology [4].

The chapters of the text were based on Mackenzie’s teachings and personal observations, the latter being all the more extraordinary since Helmholtz’s direct ophthalmoscope did not appear until 1851. The fourth edition of this book was published in 1854 and there were also German and French editions.

By now William Mackenzie was an internationally renowned ophthalmologist and well-deserved recognition was soon forthcoming. He graduated MD from Glasgow University in 1833 and was elected FRCS in 1843. His greatest honour was bestowed in 1838 when he was appointed ‘Surgeon Oculist to the Queen in Scotland’ [4].

Mackenzie was never to experience a well-earned retirement and was still examining patients the day before he died. On 29 July 1868 he suffered severe chest pains, experienced a convulsion and was pronounced dead on 30 July, aged 77.

William Mackenzie made a remarkable pioneering contribution to the ocular health of generations of his fellow citizens and placed the teaching of his medical speciality on a sound scientific footing. He was truly a founding figure of modern ophthalmology.

References

1. Wright Thomson AM: The Glasgow Eye Infirmary 1824-1962. John Smith Publishers; 1963.

2. Wright Thomson AM: The Glasgow Eye Infirmary 1823-1962. John Smith Publishers; 1963.

3. Wright Thomson AM: The Life & Times of Dr. William Mackenzie. Robert Maclehose & Co; 1973.

4. Gibson T: The Royal College of Physicians & Surgeons of Glasgow. Macdonald Publishers; 1983.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME