More effective treatments and drug delivery modalities, implantable minimally invasive glaucoma surgical (MIGS) devices, as well as accelerating clinical research programmes, will transform the surgical and clinical management of glaucoma in the near future. There is also an ever-greater emphasis on patient engagement, patient-related quality of life and real-world outcomes, and imaginative ideas on glaucoma service delivery are fast evolving.

These developments, together with practice experience and insights, were extensively reviewed during the 8th Moorfields International Glaucoma Symposium 2016.

What is the future role of implantable MIGS devices? (chairs Saab Bhermi and Emma Jones)

Trabeculectomy has persisted because the alternatives, although safer, have been predictably less effective. XEN-45 Gel Stent (AqueSys / Allergan) is a minimally invasive implantable shunt for glaucoma, has CE mark internationally, and is indicated for the reduction of intraocular pressure (IOP) in primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) patients where previous medical treatments have failed. One-year results of a multicentre study evaluating XEN-45 implantation for POAG (215 eyes) show the mean IOP was reduced by 33.7% to 13.8 ±3.7mmHg on 0.6 ±0.7 ocular hypotensive medications, with 54% of participants off glaucoma medications [1]. Ingeborg Stalmans, University Hospitals Leuven, Belgium, explained that postoperative pressures achieved using a XEN Gel Stent are reasonable for most glaucoma patients, while cases of problematic hypotony are rare.

In approaching randomised clinical trials for MIGS devices, it is necessary to assess outcomes that matter most to patients, and to assess multiple MIGS devices in head-to-head comparative superiority studies using a multiarm trial design, noted Kuang Hu.

Is dropless IOP control achievable with standalone MIGS devices?

Speaking for the debate motion that MIGS should and will be a major part of future glaucoma care, Gus Gazzard argued that most patients dislike taking hypotensive eye drops, with some heavily overtreated with topical medications. Minimally invasive glaucoma surgery procedures may offer drop freedom, or at least less intensive drop regimes. The risk benefit balance will nonetheless probably vary between different MIGS devices. Unlike trabeculectomy, long-term results for MIGS devices are lacking and current findings are misleading, as MIGS implantation is usually combined with phacoemulsification, countered John Salmon, Oxford Eye Hospital. Many patients remain on topical medication after MIGS implantation. Moreover, a MIGS procedure is not suitable for all forms of glaucoma, such as chronic angle-closure glaucoma or secondary glaucoma.

Trabeculectomy significantly reduces IOP, with 80% of glaucoma patients at risk for bleb failure achieving an IOP less than 16mmHg on no pressure-lowering medication at five-year follow-up following mitomycin C-augmented trabeculectomy [2]. More potent IOP-lowering medications will become available, and their impact is likely to be game changing. Newer glaucoma medications being investigated include a fixed combination of the Rho kinase inhibitor and norepinephrine transport inhibitor AR-13324 and latanoprost, latanoprostene bunod once daily, and a sustained release intracameral bimatoprost implant.

The patient in focus (chairs Winnie Nolan and Parham Azarbod)

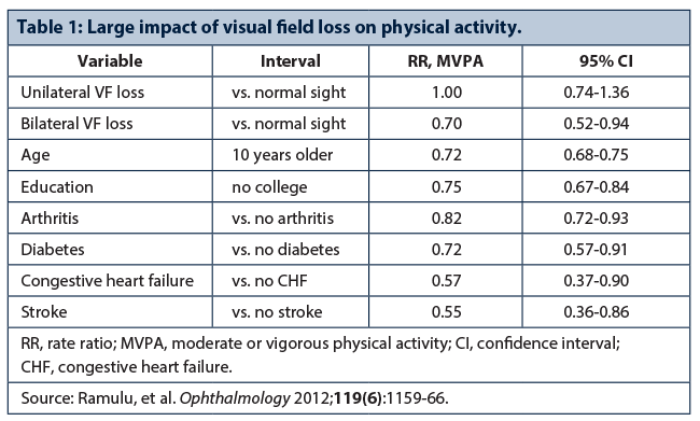

Pradeep Ramulu, John Hopkins Wilmer Eye Institute, USA, emphasised the substantial impact of glaucoma on a patient’s daily activity and behaviours (Table 1). Reading speed decreases over time in glaucoma, glaucoma severity is associated with driving cessation, with less driving reducing life space, and individuals with glaucoma are more home bound than individuals with normal vision [3]. Falls and injuries from falls are disturbingly common and are related to glaucoma severity. Fear of falling in individuals with vision loss may be closely associated with restricted physical activity. Of note, vigorous physical activity may help prevent sight loss or reduce glaucoma risk – no cases of glaucoma were seen over eight years in 781 men who ran a 10-km race in under 34 minutes [4].

Follow-up adherence may be as or more important than medication adherence in ensuring a good outcome in glaucoma care, explained Professor Shan Lin, University of California San Francisco School of Medicine, USA. A cross-sectional study in a county hospital population found that poor adherence with recommended follow-up is associated with more severe glaucoma (adjusted odds ratio 1.89, p=0.01), while patients on glaucoma medications were less adherent to follow-up recommendations (OR=3.20, p=0.01) [5]. Better workflow efficiency to reduce wait times, simplified appointment scheduling, more convenient access points, and the provision of targeted patient education and counseling by physicians, are useful strategies to improve follow-up adherence.

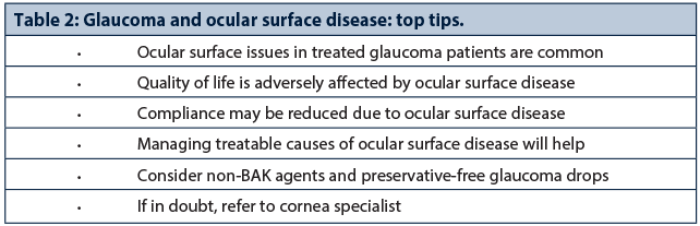

Romesh Angunawela observed that prevalence rates of ocular surface disease (OSD) in treated glaucoma patients range between 48.4% to 59.2% [6,7]. Moreover, severity of OSD symptoms is positively correlated with the number of IOP-lowering medications used. Topical use of benzalkonium (BAK) chloride causes corneal neurotoxicity, inflammation and reduced aqueous tear production, its effect is cumulative, and prolonged exposure results in cell death and disruption of the ocular surface [8]. Better control of OSD may actually improve compliance, and glaucoma specialists were encouraged to consider preservative-free topical medications for increased patient satisfaction and drop comfort, especially in younger patients (Table 2).

Patient engagement drives quality improvement

Qualitative research consistently identifies time, team and trust as the three most important topics for glaucoma patients, explained Professor Peter Shah, Birmingham & Midland Eye Centre and Good Hope Hospital. Patient-reported outcome measures are used increasingly in ophthalmic clinical trials, and may help deliver a more patient-centred approach to clinical practice. However, no single health-related quality of life instrument (patient questionnaires) covers all key domains relevant to participants. A combined qualitative instrument, a glaucoma patient-reported outcome and experience measure (POEM) has been proposed, capturing the four key glaucoma domains of knowledge and understanding, peace of mind, activities of daily living, and social relationships [9].

Prof Shah stressed that patient engagement drives quality improvement. In glaucoma patients with poor functional literacy, efforts are needed to promote health literacy to secure better compliance and disease awareness.

Hardcore research (chairs Nick Strouthidis and Ian Murdoch)

Chris Leung, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, China, discussed state of the art clinical imaging for the detection of glaucoma progression, including optical coherence tomography (OCT) retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL), optic nerve head and macular measurements. Optic nerve head surface changes can be detected prior to RNFL thinning and functional loss in experimental glaucoma. A prospective study found that a significant proportion of glaucoma patients had optic nerve head deformation, the magnitude of change in optic nerve head surface depth and anterior lamina cribrosa surface depth related to both baseline age and the averaged IOP during a mean follow-up of 5.3 years [11].

Long-term prospective follow-up studies will clarify the association between the risk of visual field progression and rate of change detected on the RNFL thickness map. Progress in anterior segment imaging and OCT angiography offers further quantifiable techniques for more precise evaluation of glaucomatous damage and disease progression.

More than 90% of patients predicted to progress to visual disability had an MD worse than 6dB in at least one eye at presentation in a retrospective study [12]. Reliable detection of significant visual field defects in primary care is therefore important. With frequent monitoring, it is possible to identify deterioration before visual field loss would likely impact on quality of life, observed Ted Garway-Heath. The IOP measurements that best predict progression rate are IOPcc (corneal compensated) and Goldmann applanation tomometry plus corneal hysteresis. Clinical trial evidence demonstrates significantly longer visual field preservation in latanoprost-treated glaucoma patients compared with a placebo-treated control arm, equating to a relative risk reduction of 52% [13].

Chris Girkin, University of Alabama at Birmingham, USA, discussed studies using quantitative imaging techniques to assess differences in optic disc, RNFL and macular structure in healthy subjects of both African and European descent. Among glaucoma patients, acquired pits of the optic nerve (APON) are associated with paracentral field loss, disc haemorrhage, notching, beta zone atrophy, low corneal hysteresis and progressive disk damage and visual field loss.

Whole-mitochondrial genome sequencing using massively parallel sequencing found a pathogenic mitochondrial DNA mutation in 50% of a cohort of high-tension POAG patients [14]. The findings support the view that mitochondrial dysfunction results in the development of glaucoma and that complex I defects play a major role in the pathogenesis of POAG, observed Professor Colin Willoughby, University of Liverpool.

Angle closure in a nutshell (chairs Gus Gazzard and Alessandra Martins)

Case series results show clear lens extraction led to a significant reduction in IOP and a reduced need for ocular hypotensive medication in eyes with primary angle closure and persistently raised IOP after laser iridotomy [15]. Three-year follow-up results from the effectiveness of early lens extraction with intraocular lens (IOL) implantation for the treatment of primary angle-closure glaucoma (EAGLE) study are expected to be published soon, explained Paul Foster. A distinguishing feature of this clinical trial is a multidimensional primary outcome measure: patient-reported outcomes (EQ-5D), IOP, and incremental cost per quality adjusted life year (QALY) gained. Practitioners are increasingly moving toward evidence-based management of primary angle-closure glaucoma (PACG), although questions remain over the optimal approach for early stage angle closure glaucoma and also in very small eyes.

Practical tips for the surgical management of angle closure

Phacoemulsification alone and combined phacotrabeculectomy both achieve good IOP control in patients with PACG and cataract, but the risk of complications is higher in those having combined phacotrabeculectomy, explained Winnie Nolan [16]. For acute primary angle closure and coexisting cataract, evidence shows that phacoemulsification and IOL implant results in a lower rate of IOP failure at two years compared with laser peripheral iridotomy [17]. Goniosynechialysis during phaco is not necessary in patients with medically well-controlled chronic angle-closure glaucoma with cataracts. For refractory acute angle closure, diode laser transcleral cyclophotocoagulation is a safe alternative to emergency lensectomy or trabeculectomy.

Practitioners were cautioned to avoid postoperative myopia in hyperopes. Lens and cataract surgery achieve good results in most cases, but trabeculectomy may be required in advanced angle-closure glaucoma. Overall, practitioners should plan for and anticipate difficulties and complications, and carefully counsel patients regarding potential surgical complications (Table 3).

Gonioscopy is often not routinely performed and is also variable and subjective among clinicians, illustrating the need to manage angle-closure glaucoma objectively and quantitatively, observed Shan Lin, University of California San Francisco, USA. Anatomic risk factors for closed angle glaucoma include anterior chamber depth, anterior chamber width, lens vault, iris thickness, angle / iris change from light to dark, and anterior chamber area. Anterior segment OCT provides an objective, repeatable and quantifiable technique, while swept source OCT creates 3D imaging of the anterior segment and can be used to assess peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS). Ultrasound biomicroscopy penetrates the iris to image the ciliary body and other structures, and is a useful backup tool for assessing the mechanism of angle closure glaucoma.

Nishani Amerasinghe, University Hospital Southampton, explained that PACG affects more than 15 million people and is a major cause of blindness worldwide. Risk factors for angle closure pathology include family history, ethnicity, increasing age and female gender. Short axial length, small corneal diameter, shallow anterior chamber, and thick relatively anteriorly positioned lens are anatomical risk factors for angle closure glaucoma.

Fishing stories from the experts (chairs Keith Barton and Dilani Siriwardena)

Unusual and interesting clinical case presentations included ocular cicatricial pemphygoid with uncontrolled IOP on multiple drops, chronic infantile neurological cutaneous and articular syndrome (CINCA), cyclodialysis clefts, schwartz-matsuo syndrome, spontaneous aqueous misdirection, and multiple tube-shunt surgeries in difficult glaucoma cases.

Mark Sherwood, University of Florida, USA, explained that approximately one in six of all cases involving primary glaucoma drainage device (GDD) implantation will ultimately require further intervention due to raised IOP, either with laser or sequential tube. Long-term efficacy data show a high initial rate of success but a relatively high likelihood of long-term failure with a sequential tube after failure of primary drainage implant, generally after six years [18]. Eyes undergoing cyclophotocoagulation tended to fail earlier but with relatively few late failures.

Most ophthalmic implanted devices are compatible and safe for magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, although some may distort radiologic images, explained Laura Crawley, Western Eye Hospital, London. The Ex-PRESS glaucoma filtration device, and gold- and platinum-weighted eyelid implants, are safe for MRI up to 3T [19]. Orbital implants after enucleation are MRI compatible.

Discussing a referred case of ocular cicatricial pemphygoid with uncontrolled IOP on multiple drops, Leon Au, Manchester Royal Eye Hospital, observed that good glaucoma assessment is essential, as is a review of past medical records to augment referral notes. In reviewing surgical treatment options, practitioners should not simply chase the pressure, but instead consider visual function, the rate of visual field progression, and risk of sight loss in the patient’s lifetime, as well as overall health and social needs. A glaucoma drainage device is probably a reasonable option to control raised IOP in a patient with ocular cicatricial pemphygoid.

Gus Gazzard described a case of blunt ocular trauma involving successful direct surgical closure of a cyclodialysis cleft, with no reformation of space one month postoperatively. Cyclodialysis clefts are frequently hidden and gonioscopy assessment may be difficult in certain instances. Anterior segment OCT or high frequency ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) may help, and a full assessment may be achieved with viscoelastic-assisted gonioscopy.

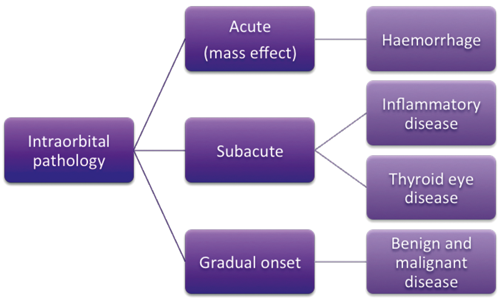

Figure 1: Intraorbital pathologies typical in a tertiary referral centre.

Glaucoma in all its guises (chairs Ananth Viswanathan and Rashmi Mathew)

Orbital disease: Intraorbital pathology may be acute (haemorrhage), subacute (e.g., inflammatory disease, such as thyroid eye disease or idiopathic inflammation) or gradual onset (benign and malignant disease), noted David Verity (Figure 1). An acute rise in orbital pressure leads rapidly to ischaemia and visual failure, with a risk of chronic compromise in orbital function. Any process embarrassing venous outflow, or an acute process which compresses the globe, can affect glaucoma. Conversely, topical ophthalmic medication can lead to periorbital hollowing due to fat atrophy, a potentially disfiguring side effect [20]. Common pathologies in a tertiary referral unit are reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, lacrimal gland inflammations, myositis and scleritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and IgG4 associated inflammation.

Corneal surgery: Leon Au reviewed glaucoma risks, both sequential and concurrent, in advanced corneal surgery. Glaucoma after graft surgery is an important cause of visual loss and graft failure. Preexisting glaucoma can complicate corneal transplantation and is associated with a significantly higher risk of corneal graft failure. In managing concurrent glaucoma and corneal disease, it is important to control the glaucoma before corneal graft surgery.

Uveitic glaucoma: Compared with matched controls, patients with noninfectious intermediate, posterior or pan uveitis face a substantial risk of ocular complications [21], observed Alastair Denniston, University Hospitals Birmingham. Common causes of visual loss in uveitis patients attending a tertiary referral uveitis service are cystoid macular oedema (CMO) (27%), cataract (18%), combined CMO and cataract (20%), and glaucoma (5%) [22]. Management principles highlighted include: assess and monitor inflammation accurately; have a systematic approach to detect patients at risk of developing uveitic glaucoma; ensure early and ongoing engagement between uveitis and glaucoma teams; control the inflammation without compromise and manage the consequences. Greater precision in the assessment of vitreous inflammation using spectral-domain OCT will help improve the clinical management of uveitis.

Optic neuropathies: Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) is a mitochondrial disease that typically causes bilateral blindness in young men, but may also affect older patients, and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of subacute blindness, said Patrick Yu-Wai-Man, Newcastle Eye Centre and Wellcome Trust Centre for Mitochondrial Research. Specialists should consider causes other than glaucoma for optic disc cupping and take a detailed clinical and family history. Pallor of the neuroretinal rim and suspicious visual field defects that respect the vertical meridian are major red flags that should not be ignored. Dominant optic atrophy can cause significant visual morbidity; it is characterised by selective retinal ganglion cell loss and is frequently misdiagnosed as normal tension glaucoma.

References

1. Barton K, Sng C, Vera V. XEN-45 implantation for primary open angle glaucoma: one-year results of a multi-center study. 12th EGS Congress, Prague, Czech Republic, 19-22 June 2016; paper submitted.

2. Casson R, Rahman R, Salmon JF. Long term results and complications of trabeculectomy augmented with low dose mitomycin C in patients at risk for filtration failure. Br J Ophthalmol 2001;85(6):686-8.

3. Ramulu PY, Hochberg C, Maul EA, et al. Glaucomatous visual field loss associated with less travel from home. Optom Vis Sci 2014;91(2):187-93.

4. Williams PT. Relationship of incident glaucoma versus physical activity and fitness in male runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009;41(8):1566-72.

5. Ung C, Zhang E, Alfaro T, et al. Glaucoma severity and medication adherence in a county hospital population. Ophthalmology 2013;120(6):1150-7.

6. Fechtner RD, Godfrey DG, Budenz D, et al. Prevalence of ocular surface complaints in patients with glaucoma using topical intraocular pressure-lowering medications. Cornea 2010;29(6):618-21.

7. Garcia-Feijoo J, Sampaolesi JR. A multicenter evaluation of ocular surface disease prevalence in patients with glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol 2012;6:441-6.

8. Sarkar J, Chaudhary S, Namavari A, et al. Corneal neurotoxicity due to topical benzalkonium chloride. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012;53(4):1792-802.

9. Somner JE, Sii F, Bourne RR, et al. Moving from PROMs to POEMs for glaucoma care: a qualitative scoping exercise. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012;53(9):5940-7.

10. Muthiah MN, Keane PA, Zhong J, et al. Adaptive optics imaging shows rescue of macula cone photoreceptors. Ophthalmology 2014;121(1):430-1.

11. Wu Z, Xu G, Weinreb RN, et al. Optic nerve head deformation in glaucoma: a prospective analysis of optic nerve head surface and lamina cribrosa surface displacement. Ophthalmology 2015;122(7):1317-29.

12. Saunders LJ, Russell RA, Kirwan JF, et al. Examining visual field loss in patients in glaucoma clinics during their predicted remaining lifetime. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014;55(1):102-9.

13. Garway-Heath DF, Crabb DP, Bunce C, et al. Latanoprost for open-angle glaucoma (UKGTS): a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385(9975):1295-304.

14. Sundaresan P, Simpson DA, Sambare C, et al. Whole-mitochondrial genome sequencing in primary open-angle glaucoma using massively parallel sequencing identifies novel and known pathogenic variants. Genet Med. 2015;17(4):279-84.

15. Dada T, Rathi A, Angmo D, et al. Clinical outcomes of clear lens extraction in eyes with primary angle closure. J Cataract Refract Surg 2015;41(7):1470-7.

16. Tham CC, Kwong YY, Leung DY, et al. Phacoemulsification versus combined phacotrabeculectomy in medically uncontrolled chronic angle closure glaucoma with cataracts. Ophthalmology 2009;116(4):725-31.

17. Husain R, Gazzard G, Aung T, et al. Initial management of acute primary angle closure: a randomized trial comparing phacoemulsification with laser peripheral iridotomy. Ophthalmology 2012;119(11):2274-81.

18. Schaefer JL, Levine MA, Martorana G, et al. Failed glaucoma drainage implant: long-term outcomes of a second glaucoma drainage device versus cyclophotocoagulation. Brit J Ophthalmol 2015;99(12):1718-24.

19. Reiter MJ, Schwope RB, Kini JA, et al. Postoperative imaging of the orbital contents. Radiographics 2015;35(1):221-34.

20. Sira M, Verity DH, Malhotra R. Topical bimatoprost 0.03% and iatrogenic eyelid and orbital lipodystrophy. Aesthet Surg J 2012;32(7):822-4.

21. Dick AD, Tundia N, Sorg R, et al. Risk of ocular complications in patients with noninfectious intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis, or panuveitis. Ophthalmology 2015 [Epub ahead of print].

22. Durrani OM, Tehrani NN, Marr JE, et al. Degree, duration, and causes of visual loss in uveitis. Br J Ophthalmol 2004;88(9):1159-62.

Acknowledgements

The article reports presentations and highlights from the 8th Moorfields International Glaucoma Symposium, 30-31 January 2016, Royal College of Physicians, London, UK. The meeting was supported by an educational grant from Théa Pharmaceuticals. Symposium planning and programme directors Nick Strouthidis, Winnie Nolan and Keith Barton reviewed the draft manuscript, and approved the final version for publication submission. Editorial development was provided by Rod McNeil, BA, MBA, which was funded by Théa Pharmaceuticals.

Declaration of Competing Interests

Keith Barton has received lecture honoraria from Allergan and Pfizer, and educational grants / research funding from AMO, New World Medical, Alcon, Merck, Allergan and Refocus. He is on the advisory boards for Glaukos, Alcon, Merck, Kowa, Amakem, Thea, Alimera, Refocus and Ivantis, and works as a consultant for Alcon, Aquesys, Ivantis, Refocus and Carl Zeiss Meditec. He also holds shares in AqueSys, Ophthalmic Implants (PTE) Ltd, Vision Futures (UK) Ltd (Director), London Claremont Clinic Ltd (Director) and Vision Medical Events Ltd (Director).

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME