The people of the United Kingdom voted by 52% to 48% to leave the European Union (EU) in June 2016, a referendum decision intended by a slim majority to restore national self-determination and achieve what many believed to be a favourable outcome for Britain. The author considers priorities that will shape exit from the EU, the projected economic impact and thought-provoking perspectives on prospects for post-Brexit Britain.

What is happening?

The Prime Minister set out in January 2017 the 12 principles which will guide the Government in fulfilling the democratic will of the people of the UK (Table 1). “We do not approach these negotiations expecting failure, but anticipating success,” Theresa May stated.

In a preface to the Government’s White Paper outlining its vision on EU exit negotiations [1], David Davis MP, Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union, explained: “The referendum result was not a vote to turn our back on Europe. Rather, it was a vote of confidence in the UK’s ability to succeed in the world – an expression of optimism that our best days are still to come. Whatever the outcome of our negotiations, we will seek a more open, outward-looking, confident and fairer UK, which works for all.”

There will be no attempt to remain in the EU by a backdoor solution, nor will there be a second referendum on membership. The Government’s free market rhetoric is impressive too: “a sovereign UK and a thriving EU will be at the heart of a new global Britain” [1].

How will this happen?

On 29 March 2017, the Government triggered Article 50 [2] of the Treaty on European Union and formally notified the European Council of the UK’s intention to withdraw from the EU, with a deadline of March 2019. Priorities for exit negotiations are securing a comprehensive agreement while seeking to advance and protect shared European values. Of note, the Prime Minister proposed a bold and ambitious Free Trade Agreement between the UK and the EU. “We recognise that it will be a challenge to reach such a comprehensive agreement within the two-year period set out for withdrawal discussions in the Treaty,” wrote Theresa May. “But we believe it is necessary to agree the terms of our future partnership alongside those of our withdrawal from the EU.”

The Great Repeal Bill will repeal the European Communities Act 1972 on the day of exit from the EU and return power to UK institutions, convert EU law at the moment of exit into UK law before leaving the EU, and finally create powers to make secondary legislation.

This legislation will, wherever practical and appropriate, in effect convert the body of existing EU law into UK law. This means there will be certainty for UK citizens and for anybody from the EU who does business in the UK. In order to achieve a stable and smooth transition, the Government’s overall approach is to convert the body of existing EU law into domestic law, after which Parliament (and, where appropriate, the devolved legislatures) will be able to decide which elements of that law to keep, amend or repeal once the UK has left the EU. This ensures that, as a general rule, the same rules and laws will apply after EU departure as they did before. However, the Great Repeal Bill will end the general supremacy of EU law.

What are the immediate prospects for the UK economy?

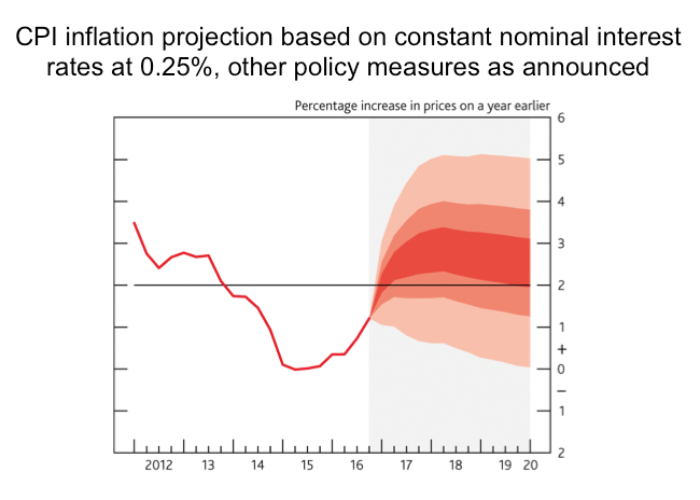

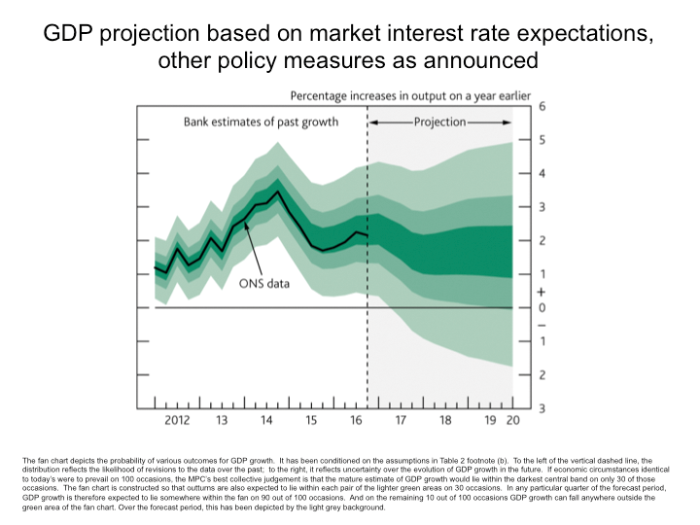

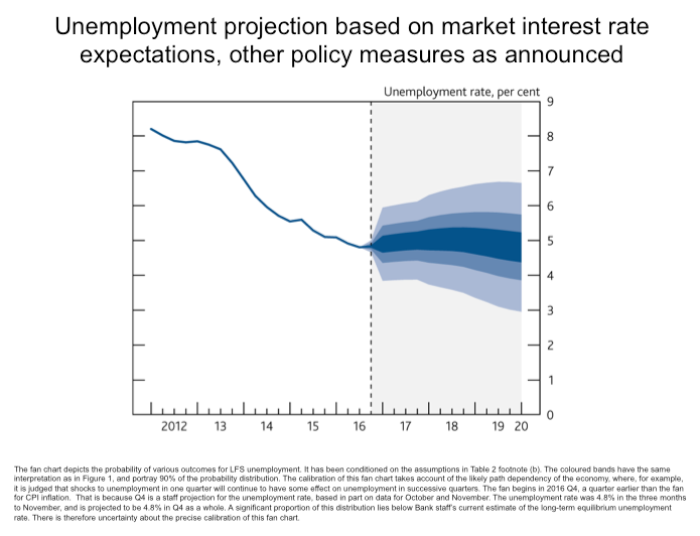

The Bank of England observed in its February 2017 Inflation Report that growth has been stronger than envisaged in the immediate aftermath of the vote to leave the EU when survey evidence pointed to a sharp slowdown in activity [2]. Overall, the central growth projection leaves the level of gross domestic product (GDP) around 1% higher in three years’ time than projected last November. Annual growth in real GDP is forecast at 2% in 2017, 1.6% in 2018 and 1.7% in 2019. Relative to expectations just before the EU referendum, however, the level of GDP is still around 1.5% lower in the medium term despite the significant monetary, macroprudential and fiscal support since then. Forecasts and projections on key economic indicators from the Bank of England are detailed in Tables 2 and 3 and Figures 1-3 [2].

Table 2: Forecast economic indicators, Bank of England. [2]

Table 3: Other forecasters’ central projections, Bank of England. [2]

The World Bank pointed to weak investment and subdued growth amidst heightened uncertainty, in the January 2017 global economic prospects report [3]. Stagnant global trade, subdued investment, and heightened policy uncertainty marked another difficult year for the world economy. Global growth in 2016 is estimated at a post-crisis low of 2.3% and is projected to rise to 2.7% in 2017. Although fiscal stimulus in major economies, if implemented, may boost global growth above expectations, risks to growth forecasts remain tilted to the downside due to heightened policy uncertainty in major economies.

After slowing to 1.6% in 2016, growth is projected to recover somewhat in 2017-19, although the range of possible outcomes has significantly widened after the elections in the United States and the UK’s decision to leave the EU. Growth projections for 2017 and 2018 have been revised down for the Euro Area and, especially, for the UK. Uncertainty about the Brexit process is expected to weigh on growth in 2017-18 in the UK and, to a lesser extent, in the Euro Area. Growth in the Euro Area in 2017 is projected to slow marginally to 1.5%, as the unwinding of the income boost associated with lower oil prices, increased policy uncertainties, and lingering banking sector concerns offset the benefit of more favourable financial conditions. Growth is expected to remain broadly stable in 2018 and 2019, at 1.4%, leading to a very gradual narrowing of the output gap.

Figure 1: Consumer Price Index (CPI) projection, Bank of England. [2]

Figure 2: Gross Domestic Product (GDP) projection, Bank of England. [2]

Figure 3: Unemployment projection, Bank of England. [2]

What do others think of Britain’s post-Brexit prospects?

To gauge the spectrum of sentiment and perspectives on prospects for Britain following EU withdrawal, the author undertook a series of interviews with respected economists and policy specialists from the Adam Smith Institute, Capital Economics and King’s College London.

“Most of us felt that leaving the EU would be fine if we remained within the single market, similar to the Norway option, with flexibility to forge our own trade deals with the rest of the world,” commented Sam Bowman, Executive Director of the Adam Smith Institute, one of the world’s leading think tanks. “But it is undeniable that leaving the single market will harm the UK economy with decreased productivity overall, at least in the short- term, although forecasters believe substantial job losses in the medium term are unlikely.”

“The obvious question concerning post-Brexit relates to what sort of deal we secure with EU member states,” continued Mr Bowman. “It would be much better if we secured a comprehensive trade deal but there isn’t much time to achieve that. The decision to call a general election for June is probably the right move. Assuming the election result gives Theresa May a bigger majority, she is more likely to get the backbench support she needs for negotiating a compromise transitional arrangement that avoids short-term disruption by having to revert to World Trade Organisation-rules and disruptive trade tariffs. This should make the exit from the EU much softer hopefully and entail a phased adjustment to free movement.”

“Events post Brexit will punish Britain soon enough”

Mr Bowman considered: “I don’t really believe that the EU will try to punish Britain for leaving. Why? Because it is going to be quite harmful to Britain to leave the EU so therefore they won’t need to punish us, as events and reality will do that soon enough.

“The EU single market is a deep and comprehensive trade deal. It is likely therefore that we will be poorer by leaving, at least in the short-term, but people considered national sovereignty and immigration were more important. It is possible that other things that we do will offset that and perhaps make us richer than otherwise would have been the case with the power that we have outside the EU. For example, by securing rapid trade deals with the US, China, India, South Korea, Japan and Mexico through a mutual recognition approach.”

“I suspect this is not positive news for the National Health Service (NHS),” added Mr Bowman. “Tax receipts will either fall or stagnate, which means NHS funding will continue to be quite tight. But the big issue facing the NHS is staffing and employment. If we end freedom of movement eventually, as seems likely, that will make it much more difficult, costly and time-consuming for the NHS to employ those it wants to employ from overseas. A quasi-Swedish system might be achievable whereby everyone who has a job offer from the NHS qualifies for a work visa. But this doesn’t necessarily solve the NHS recruitment challenge.”

“The economic benefits of EU membership have been greatly exaggerated”

Capital Economics, a global independent macroeconomic research company, was among the first to predict sterling’s decline to around $1.20 if the UK voted in favour of Brexit. Significantly, the company believes Brexit will be rather less damaging than many forecasters predict.

Roger Bootle, Executive Chairman of Capital Economics, explained: “The economic benefits of EU membership have been greatly exaggerated. I don’t think there is any convincing evidence that being in the EU and the single market specifically has conferred prosperity upon its members, certainly not in more recent years.”

He argues that the EU is a failing project, with an increasingly uncertain political landscape ahead, and that Britain can thrive with greater prosperity outside the single common market.

“There are lots of interferences and burdens that accompany EU membership, notably regulatory harmonisation and tariffs. Britain has to impose the EU common external tariff on imports from the outside world and if we were outside the EU we wouldn’t have to do that. That holds out the prospect of a great surge in trade and all the beneficial effects that come from that. On top of that there is the question of the annual contribution to the EU budget, albeit in net terms less than 0.5% of Britain’s GDP.

“Those who argue that exit from the EU is very much to our disadvantage tend to use a model of international trade called the gravity model, which assumes there are overwhelming advantages to conducting trade with people that are geographically close to you,” continued Mr Bootle. “Second, they assume that Britain will find it difficult to get free trade agreements with other countries around the world. There is powerful evidence showing this is complete nonsense. Actually the EU is a poor trade negotiator and you don’t have to be Albert Einstein to understand why: it has to get 28 different member states to agree on everything before moving forward.”

A bold comprehensive free trade agreement with the EU is a tenable prospect but it’s by no means in the bag. “And given the pressure of time, it’s going to be tough to secure such an agreement for day one post-Brexit,” Mr Bootle added. “The fall of the pound has been extremely helpful and we desperately need to export more and import less, with a rebalancing of the economy towards production of more traded goods and services. Britain will continue to be extremely successful in business and financial services, high-tech manufacturing and in health and scientific research, leadership strengths that are unlikely to diminish as a result of Brexit.

“The economic and social benefit of free movement is a vexed issue and you must draw a distinction between the overall level of GDP and the level of GDP per head of population to properly evaluate the impact on real world living standards. My own view is that we should seek to preserve access to quite significant levels of net migration of highly skilled people.”

“Brexit-associated reductions in migration will hit per capita GDP growth”

An empirical research analysis by Portes and Forte suggests that a sharp fall in migration post Brexit could shrink GDP per capita by more than 3% over the period to 2030 [4]. The broad scenarios (not forecasts) depicted imply that the negative impacts on per capita GDP will be significant, potentially approaching those resulting from reduced trade. By contrast, the increase in low-skilled wages resulting from reduced migration is expected to be relatively modest.

EU migration to the UK could fall by well over half over the period from now to 2020, resulting in net EU migration falling by more than 100,000, according to estimates from the National Institute of Economic and Social Research. The reduction in migration would also lead to a significant reduction in GDP per capita – up to 3.4% over the period to 2030.

Jonathan Portes, Professor of Economics and Public Policy in the Department of Political Economy, King’s College London, commented on economic prospects post-Brexit: “The immediate Brexit developments have shown that one should not be too over confident in making predictions. My view remains pretty much what it was a year ago, which is that, over the medium to long-term, Brexit will make us poorer. We shouldn’t exaggerate or understate the likely impact. The most likely outcome is that Brexit will make Britain significantly poorer, but not disastrously poorer. That is to say it will knock a few percentage points off per capita GDP over the next 15 years or so relative to what it would otherwise have been.

“That impact will be noticeable but Britain will still be an advanced rich economy. However, there will be a noticeable slip in living standards relative to other comparable factors. But these are predictions only. Things could be considerably worse or considerably better. But I don’t believe there is any plausible scenario under which Brexit will make Britain better off.”

“Based on our estimates,” continued Prof Portes, “Brexit will lead to a sharp reduction in migration to the UK and that is likely to have quite significant negative economic consequences. But it is important to emphasise both the uncertainty about these estimates and that it is not the end of the world. Free movement has resulted in a large increase in migration and that has been good for the British economy, and reversing free movement is likely to reverse that benefit. Economies don’t just benefit from highly skilled workers. They benefit from workers who come here to work to fill gaps in the labour market, increasing the flexibility of the economy and increasing productivity by having labour available in the right place at the right time to do the right things. The claim often made that most European migrants are unskilled is just not true.”

On the likely future landscape following EU withdrawal, Prof Portes observed: “An extended transitional agreement under which we effectively for practical purposes see very little change, under which we leave the EU in a political sense but stay linked through a common economic and legal framework, would obviously make the benign economic scenario much more likely. And this would provide a great deal more time for adjustments and make it more likely that major negative outcomes can be avoided or mitigated.”

Amidst policy drift stemming from an unpredictable political landscape here and in the Euro area, sluggish economic growth over the near term appears likely. Nevertheless, there may well be good reasons to be cheerful about Britain’s outlook after Brexit. The shock of uncertainty in denting confidence and hence investment and spending patterns may have been overplayed. Breaking free from the perceived shackles of Strasbourg and Brussels may spur or necessitate bolder and broader domestic and international policy initiatives that strengthen the national interest.

What concerns ophthalmologists?

Conversations with consultant ophthalmologists underscore current concerns about the consequences of Brexit:

- “My personal concerns are about the potential impact of Brexit on Ireland and the future of UK / Ireland borders. On the research funding front, there is talk of retrenchment or realignment by the Medical Research Council.”

- “The economy will drive everything to do with the public purse and hence NHS funding. For successful Brexit negotiations, there must be a win-win solution for Britain and EU member states.”

- “Human resources for eye care is a concern. We take too many staff from parts of the world that can ill afford it. Some European countries have too many doctors while others, like the UK, do not have enough. Anything that reduces the ability to redistribute human resources is a bad thing.”

Medicines regulation?

At the end of April, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and heads of national competent authorities met to discuss how the work related to the evaluation and monitoring of medicines will be shared between member states as a result of UK withdrawal from the EU. Although negotiations on the terms of the UK’s departure have not yet officially commenced and one cannot prejudge their outcome, said the EMA, work will now start on the basis of the scenario that foresees that the UK will no longer participate in the work of EMA and the European medicines regulatory system as of 30 March 2019.

Due to the current restrictions of the pre-election period, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) were unable to comment further at this time. It has said previously that the MHRA will be engaging widely with its stakeholders to fully understand and maximise the opportunities of Brexit.

For the MHRA, playing a full, active role in European regulatory procedures for medicines remains a priority. In a prior statement, the MHRA said: “We contribute significantly in both the centralised and decentralised regulatory procedures, including new rapporteur and reference member state (RMS) appointments, and maintain our programmes for implementing EU legislation as required by our obligations as a Member State. We are also fully engaged in European and national scientific advice services and in delivering our EU inspection-related duties.”

References

1. The United Kingdom’s exit from and new partnership with the European Union. Presented to Parliament by the Prime Minister by Command of Her Majesty. February 2017. Crown Copyright 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/

uploads/system/uploads/

attachment_data/file/589189/

The_United_Kingdoms_exit_from

_and_partnership_with_the_EU_Print.pdf.

Last accessed May 2017.

2. Inflation Report. Bank of England. February 2017.

www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/

Pages/inflationreport/2017/feb.aspx.

Last accessed May 2017.

3. World Bank Group. 2017. Global Economic Prospects, January 2017 Weak Investment in Uncertain Times. Washington, DC: World Bank. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

4. Portes J, Forte G. The economic impact of Brexit-induced reductions in migration. National Institute of Economic and Social Research. December 2016.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME