As elective cataract services restart post-COVID, how do we establish which patients should be a priority? The authors share their findings from a review of ‘urgent’ referrals received by the ophthalmology department in NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde.

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in the variable suspension of elective surgical procedures in the UK since March 2020, affecting routine cataract surgery provision. Re-mobilisation plans related to prioritising clinical needs have been developed by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists to aid ophthalmic services in the setting of reduced outpatient capacity [1-4].

A high–low traffic light system was proposed to represent risk of harm due to delays. Levels of referrals identified same day emergencies, urgent (within seven days), then appointments within 14 days, within 30 days and above 30 days [2]. This document only advised that complicated postoperative cataract patients should be prioritised for review within 14 days, and severely visually impaired cataract patients should be seen within 30 days due to the potential risk for harm if subjected to delays.

However, there is no system that we are aware of that advises optometrists or primary eye care services regarding the urgency of cataract referrals (either prior to, or in response to, COVID-19 limitations) [5-7]. This creates an obvious issue during a time of limited clinical capacity or theatre access. Currently in the West of Scotland, patients can only be referred to outpatient services as ‘urgent’ or ‘routine’. Traditionally, urgent appointments are expected to be seen within two weeks. The 2011 Patients Right Act (Scotland) outlines urgency of referral as an individual clinical decision, yet it advises that all referrals should be both appointed and treated within 18 weeks (in accordance with the Scottish Referral to Treatment targets) [8,9]. Obviously these ambitions have not been achieved in the light of the COVID-19 capacity restrictions, elective service suspensions and staff redeployments [10]. It should be noted that there is no ‘soon’ referral category in NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde, so outside of emergency referrals only two levels of clinical prioritisation exist for referring optometrists in the West of Scotland (urgent and routine) [6,7].

“If all patient referrals become urgent, then none will be urgent, so this pressure to request sooner engagement on referrals must be resisted”

In light of this, we wanted to evaluate recent cataract referrals which had been requested as ‘urgent’, to identify any objective or subjective optometric comments prompting the request for higher prioritisation.

Methods

This study was discussed with the West of Scotland Ethics Committee and as it was deemed to be an audit of established clinical practice, no additional ethical permissions were required. The principles of the Declaration of Helsinki were maintained throughout this audit.

We performed a retrospective review of all electronic ‘urgent’ referrals received by the ophthalmology department in NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde between 1 September 2018 and 31 August 2020. We selected those with a referral diagnosis of cataract and reviewed the referral letter details to identify documented evidence for this requested degree of urgency.

Results

We identified 128 ‘urgent cataract’ referrals in this two-year period. All the referrals originated from community optometrists in the West of Scotland, with an average of five urgent cataract referrals received per month (range 1-14). These referrals related to 62 males and 66 females, with a median age of 67.7 +/-14.7 years (range 22-90).

Objective information

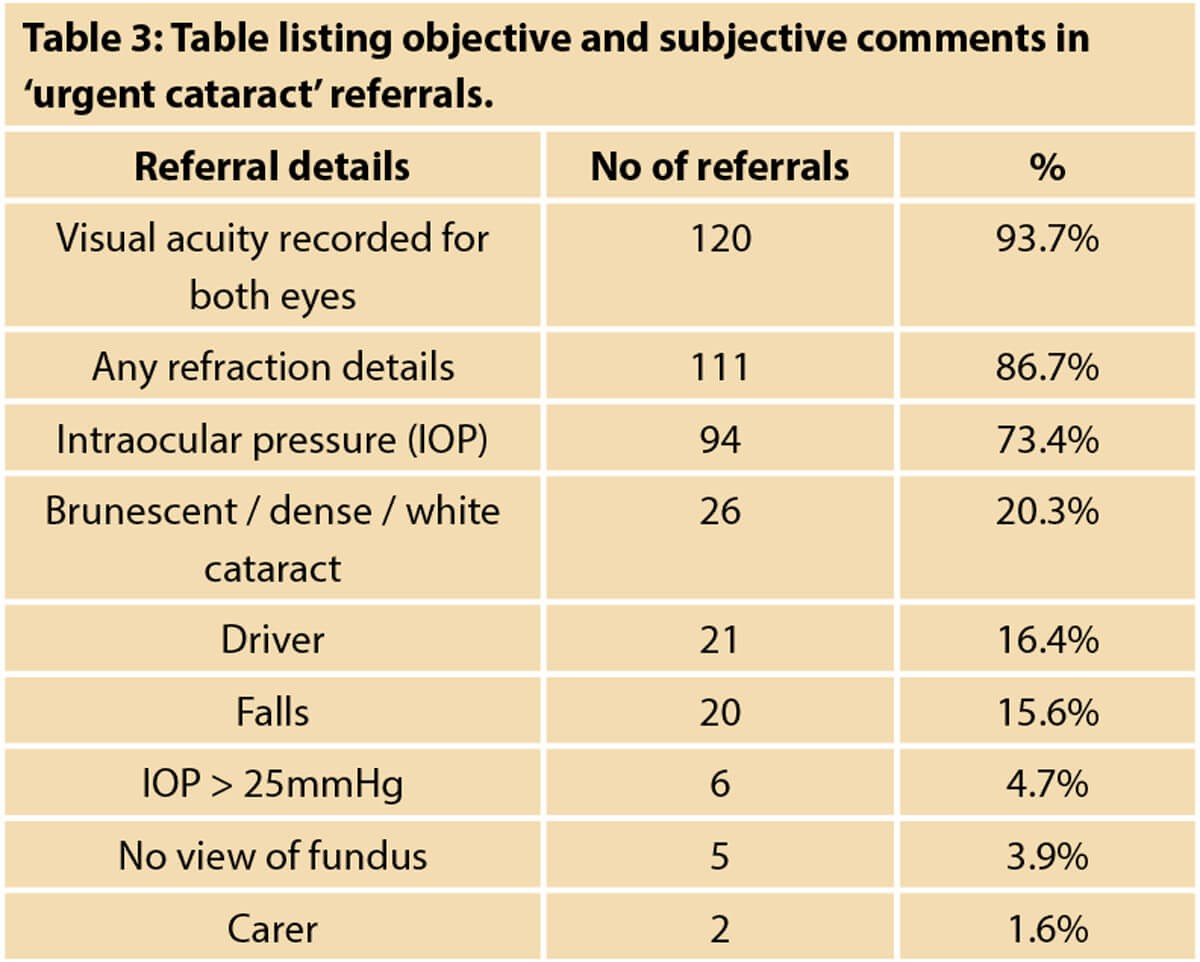

Visual acuity for both eyes was documented in 120 patients (93.7%). Any refraction measurement was documented for 111 patients (86.7%). Intraocular pressure was documented for 94 patients (73.4%). A dense cataract (brunescent, white, or no fundal view) was described in 31 patients (24.2%). Four patients (0.7%) had an additional primary diagnosis other than cataract included with their urgent referral.

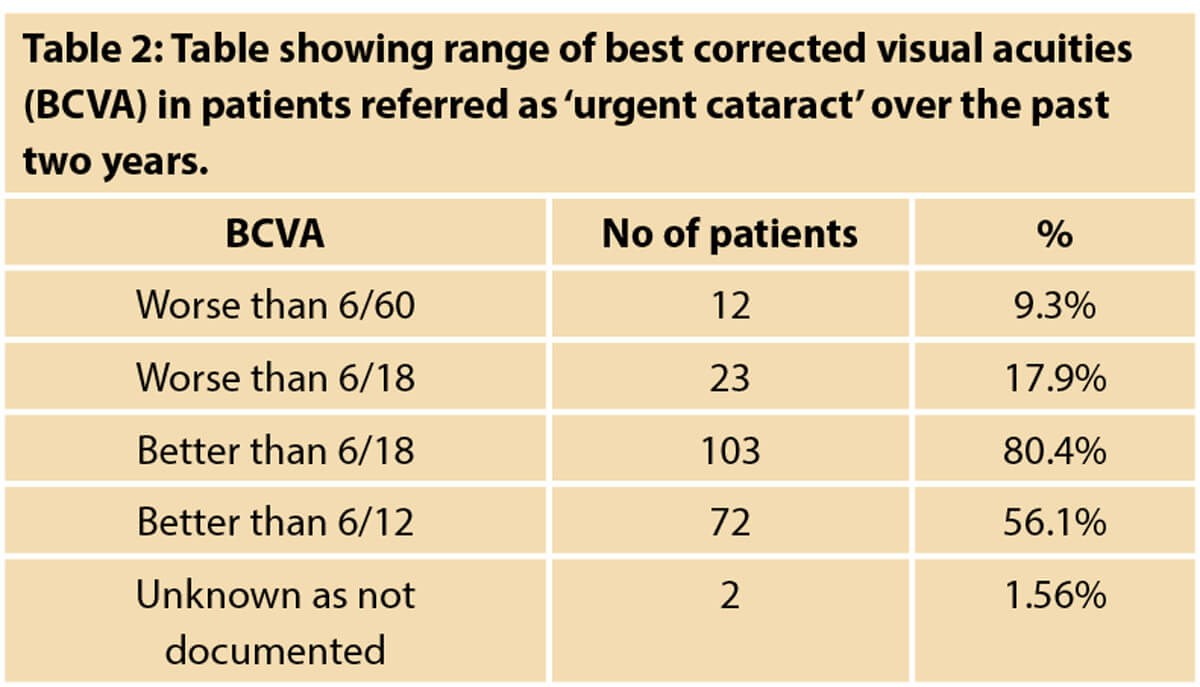

Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA)

Twenty-three patients (17.9%) had BCVA worse than 6/18 Snellen, of which 12 patients (9.3%) had BCVA worse than 6/60 Snellen. It was also noted in this ‘urgent’ referral group that 103 patients (80.4%) had BCVA of 6/18 or better, of which 72 (56.25%) were BCVA 6/12 or better.

Subjective free text comments

Additional personalised free text comments were present on 92 referrals (71.8%), including concerns with recent falls (20 patients; 15.6%), unable to work or perform daily activities (14 patients; 10.9%). Other comments included “being a driver” in 21 cases (16.4%), “only eye” in eight cases (6.3%), terminal ill-health (three patients; 2.3%), and “main carer” in two patients (1.6%). “Delay in assessment” was highlighted for nine patients (7%) (see tables).

Accuracy of diagnosis

The conversion rate of visually significant cataract requiring surgery in this ‘urgent’ referral group was 86.7% (111/128 patients). Of the other 17 referrals, eight were discharged without requiring cataract surgery and six received a non-cataract diagnosis. The remaining three referrals had been re-categorised as ‘routine’ prior to assessment.

Discussion

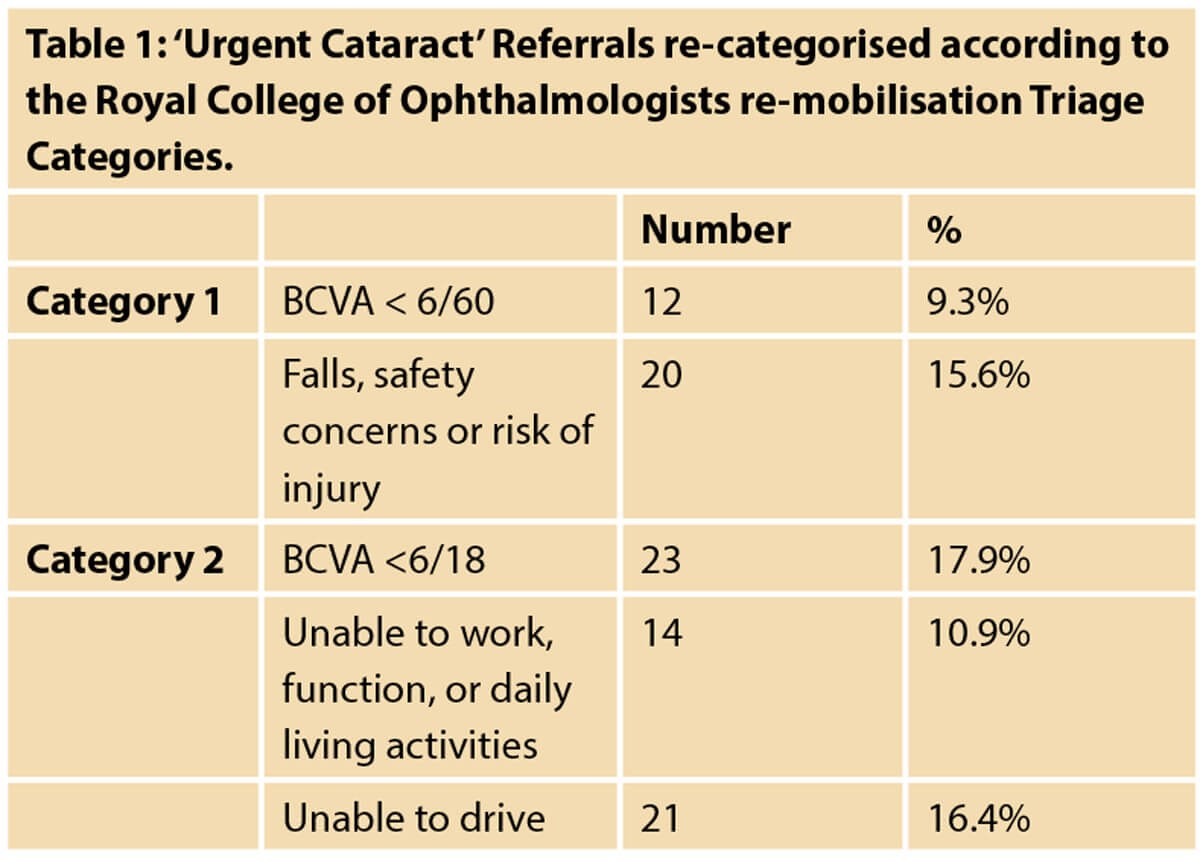

The Royal College of Ophthalmologists’ guidance for prioritisation of ophthalmic outpatient appointments published in May 2020 in response to the COVID-19 restrictions suggested two higher prioritisation categories to identify patients who are at greatest risk of harm from delay to appointment [1-3]. Priority 1 patients included those with “BCVA worse than 6/60 or at risk of fall / injury, or inability to function”, and Priority 2 patients with “cataract with BCVA worse than 6/18 and unable to drive / work / function”. These guidelines recommended patients meeting these criteria should receive an ophthalmology appointment within 30 days.

Retrospectively applying these guidelines to our referral cohort highlights the challenge and controversy in identifying urgent cataract patients based on BCVA alone [5]. Only 9.3% (12 patients) met the priority 1 level of vision with 56.2% (72 patients) having BCVA better than 6/12.

The variability within community optometric referral behaviour was demonstrated when judging clinical urgency based on cataract patients’ activities of daily living. Only 20 cases (15.6%) reported loss of mobility / independence / falls, and 14 cases (10.9%) reported loss of employment. Unsafe vision for driving was only described in 21 cases (16.4%), 42.9% of which (9/21) had a BCVA recorded better than 6/12.

Although the majority of these urgent cataract referrals (92/128; 71.8%) contained additional subjective comments describing how visual loss was affecting the patient’s individual circumstances, this information fell outside the RCOphth Category 1 or 2 clinical prioritisation guidelines in 49 cases (equating to 53.2% of this ‘additional comments’ sub-group).

A referring optometrist may assume that the hospital eye service will downgrade urgent referrals to routine based on clinical findings or service capacity. Analysis of the referrals found a lack of significant clinical information (no documented visual acuity for both eyes in eight referrals (6.3%), no recorded refraction of any type (recent / historic) in 17 (13.3%) and intraocular pressure was missing in 34 (26.6%). Without these three measures, 46% of referrals did not contain sufficient clinical information to enable clinicians to evaluate the level of urgency or priority for those patients prior to a hospital clinical appointment. We only identified three referrals which had been downgraded to ‘routine’.

National Institute of Health & Care Excellence (NICE) guidance is clear that any decision to refer for surgery is multi-factorial, that shared decision making with patients is essential and access to surgery should not be restricted based on visual acuity alone [5]. However, our analysis of ‘urgent’ referrals demonstrates that there are variable sub-groups of patients who have greater levels of visual impairment at presentation and who would benefit from greater surgical prioritisation. The Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) national report and many cataract service redesign proposals all promote the use of patient surgery decision making aids (PSDMA) to streamline clinical prioritisation decisions [11-13]. These PSDMA assume that patients at greatest risk are being effectively identified in the community as higher priority and the correct patients are streamlined to secondary care. Our study would suggest inconsistencies exist in the judgement of urgency of cataract referrals between patients and community optometrists.

As elective cataract services restart in a post-COVID landscape, we can expect both a large backlog of cataract referrals with an increased volume of advanced disease presentations and potential harm due to delay [14]. It would be helpful if the College of Optometrists and the Royal College of Ophthalmologists could provide specific guidance for the referring optometrists to ensure best prioritisation of the ‘urgent’ referral pathway. If this does not happen, then optometrists will continue to apply subjective criteria to make ‘urgent’ cataract referrals, which will likely compound the pressure on clinical capacity and make it more difficult to identify those who should be of greater priority. If all patient referrals become urgent, then none will be urgent, so this pressure to request sooner engagement on referrals must be resisted, or targeted justification provided to enable objective decisions to be made. The ‘Getting It Right First Time’ principles should also apply to referrals to ensure efficient and effective patient prioritisation [11].

We had wondered if the effect of national Tier 4 lockdown restrictions would influence the rate of ‘urgent’ cataract referrals as community optometrists were closed for several months from March 2020. However, although lockdown unequally divided the two-year study period, there was no difference observed in the rate of ‘urgent’ referrals received (mean of five per month pre- and post-March 2020).

Conclusion

Our study has demonstrated variability in the quality of the objective and subjective information provided in ‘urgent’ cataract referrals from community optometrists in West of Scotland over this two-year period. We propose objective referral guidelines are developed to ensure best utilisation of cataract service capacity with appropriate prioritisation for those patients with greater levels of visual impairment. Such directives should preserve and protect the limited availability of urgent clinical appointments for the correct patients, by ensuring adherence to ‘Getting It Right First Time’ and ‘Realistic Medicine’ principles in the recovery period following COVID-19 service disruption and beyond.

References

1. Royal College of Ophthalmologists Ophthalmic Service Guideline. Restarting and Redesigning of Cataract Pathways in response to Covid 19 Pandemic. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists, August 2020:

www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/

uploads/2020/08/Resumption-of-Cataract

-Services-COVID-August-2020-2.pdf

2. Royal College of Ophthalmologists: Guidance Document: Prioritisation of ophthalmic outpatient appointments. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists, London, May 2020:

www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/

uploads/2020/06/Prioritisation-of-ophthalmic

-outpatient-appointments.pdf

3. Royal College of Ophthalmologists: Guidance Document. Prioritisation of ophthalmic procedures. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists, London, May 2020:

www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/

uploads/2020/05/Prioritisation-of-ophthalmic

-procedures-COVID19-1.pdf

4. Royal College of Ophthalmologists: Guidance Document. Guidance on the Resumption of Cataract Services during COVID. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists, London, May 2020:

www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/

uploads/2020/05/Resumption-of-Cataract

-Services-During-COVID-1.pdf

5. NICE Guideline NG 77: Cataracts in Adults. 2017:

www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng77/

chapter/Recommendations#referral

-for-cataract-surgery

6. College of Optometrists. Urgency of Referrals. College of Optometrists 2020:

https://guidance.college-optometrists.org/

guidance-contents/annexes/

annex-4-urgency-of-referrals/

7. College of Optometrists. Examining patients who present as an emergency. College of Optometry 2020:

https://guidance.college-optometrists.org/

guidance-contents/knowledge-skills-and

-performance-domain/examining-patients

-who-present-as-an-emergency

8. Scottish Government. NHS Scotland Waiting Time Guidance. Scottish Government July 2012:

www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/

mels/CEL2012_33.pdf

9. Scottish Government. Treatment Time Guarantee Guidance. Patient Rights Act (Scotland) 2011:

www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/

mels/CEL2012_32.pdf

10. Public Health Scotland. Inpatient, Day Case and Outpatient Stage of Treatment Waiting Times Quarterly data ending 30 September 2020:

https://beta.isdscotland.org/

find-publications-and-data/healthcare

-resources/waiting-times/nhs

-waiting-times-stage-of-treatment

11. MacEwan C, Davis A, Chang L. Ophthalmology GIRFT Programme National Specialty Report. December 2019:

https://gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk/

wp-content/uploads/2019/12/

OphthalmologyReportGIRFT19P-FINAL.pdf

12. United Kingdom & Ireland Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery & Royal College of Ophthalmology Cataract Surgery Guidelines for the Post COVID-19 Era: Recommendations. May 2020:

www.ukiscrs.org.uk/resource/Post-COVID

-cataract-surgery-guidelines-UKISCRS

-May-2020_FINAL.pdf

13. Lin PF, Naveed H, Eleftheriadou M, et al. Cataract service redesign in the post-COVID-19 era. Br J Ophthalmol 2020 Jul;Epub ahead of print.

14. Foot B, MacEwen C. Surveillance of sight loss due to delay in ophthalmic treatment or review: frequency, cause and outcome. Eye (Lond) 2017;31(5):771-5.

(All links last accessed April 2021)

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.

Acknowledgements: A version of this paper won Best Quality Improvement e-poster at the Virtual Scottish Ophthalmological Club meeting in February 2021.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME