Rod McNeil reviews plans, activity and solutions to better address the post-COVID backlog and bolster sustainable service recovery.

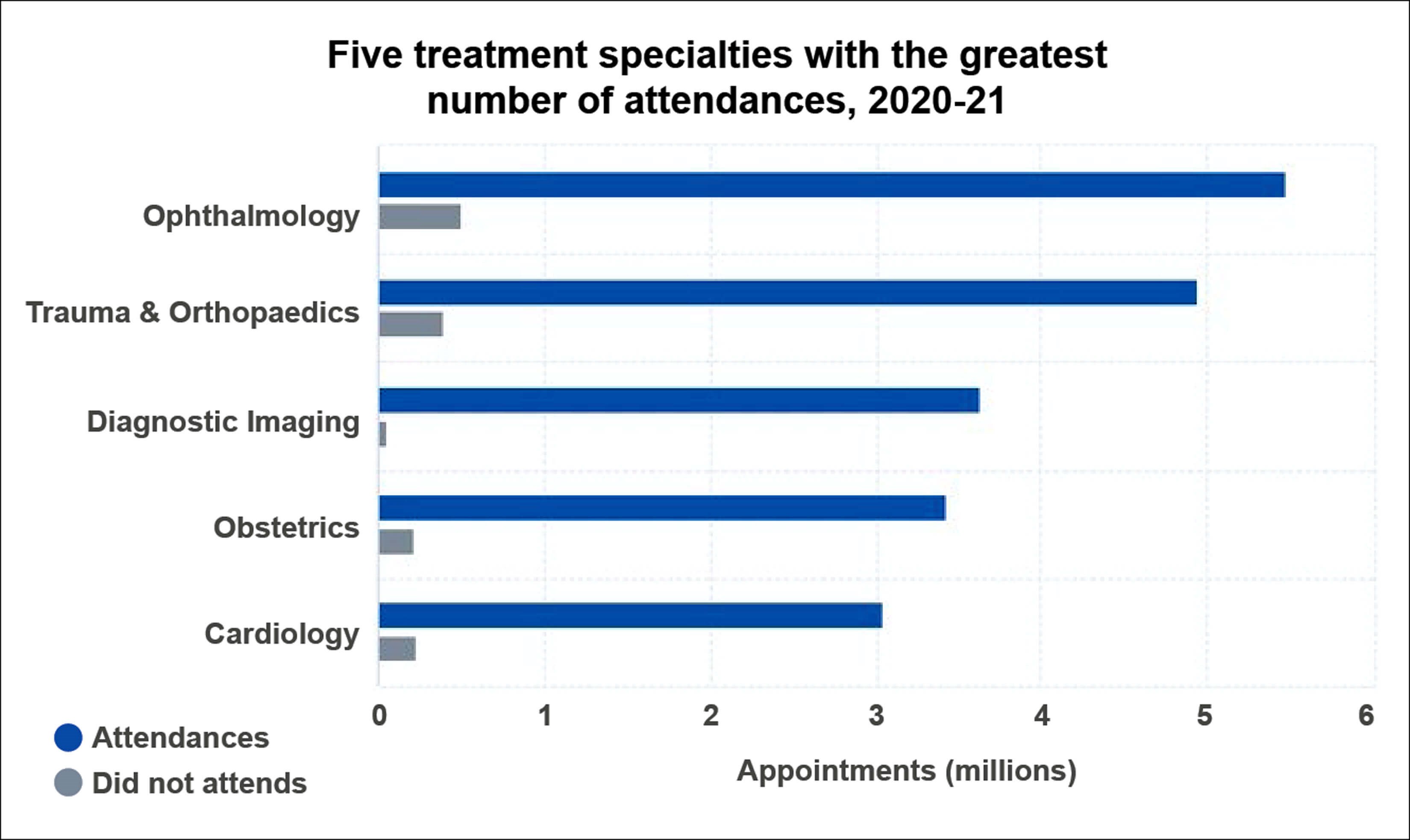

Ophthalmology was the busiest outpatient specialty during the three years to March 2020 across the English NHS and again recorded the highest levels of attendances during 2020–21, with 5.5 million visits, compared with 4.9 million in trauma and orthopaedics, and 3.6 million for diagnostic imaging specialties (Figure 1) [1].

Figure 1: Outpatient attendances by specialty, 2020-21.

Source: NHS Digital. Hospital Outpatient Activity 2020-21.

Across specialties, ophthalmology had the lowest ratio between Attended and Did Not Attend appointments, with approximately 10.8 attendances for each appointment where the patient did not attend.

Return to pre-pandemic performance

As of February 2022, six million people were on the waiting list for elective care, up from 4.4 million before the pandemic and an increase of 36% [2]. Hidden demand likely means that the true waiting list could be significantly higher. The National Audit Office estimated that elective care waiting lists would hit 12 million by March 2025 if half of ‘missing’ referrals for elective care return to the NHS but activity increases only in line with pre-pandemic plans [3].

Government funding for elective recovery includes more than £8 billion from 2022/23 to 2024/25, supported by a £5.9 billion capital investment. The latter includes £2.1 billion to modernise frontline digital technology, improve cyber security and use of data and redesign care pathways.

The NHS Chief Executive describes the COVID-19 elective care backlog as a multi-year challenge [2]. By November 2021, elective and diagnostics activity levels in many areas had recovered towards or above pre-pandemic levels, revealing good progress.

The NHS national plan for tackling the COVID-19 backlog of elective care, published in February 2022, outlines what it calls realistic but ambitious actions and principles to help local NHS organisations use additional investment to build on current momentum, and go “further and faster”, i.e., transforming services, harnessing the potential of data and technology, and expanding the workforce and physical capacity [2].

The plan sets out a progressive agenda for how the NHS will recover elective care over the next three years, capturing a range of ambitions:

- Waits of longer than one year for elective care are eliminated by March 2025.

- Some 95% of patients needing a diagnostic test receive it within six weeks by March 2025.

- By March 2024, 75% of patients who have been urgently referred by their GP for suspected cancer are diagnosed or have cancer ruled out within 28 days.

- Transforming the model of care and making greater use of technology to reduce waiting times for first outpatient appointments over the next three years.

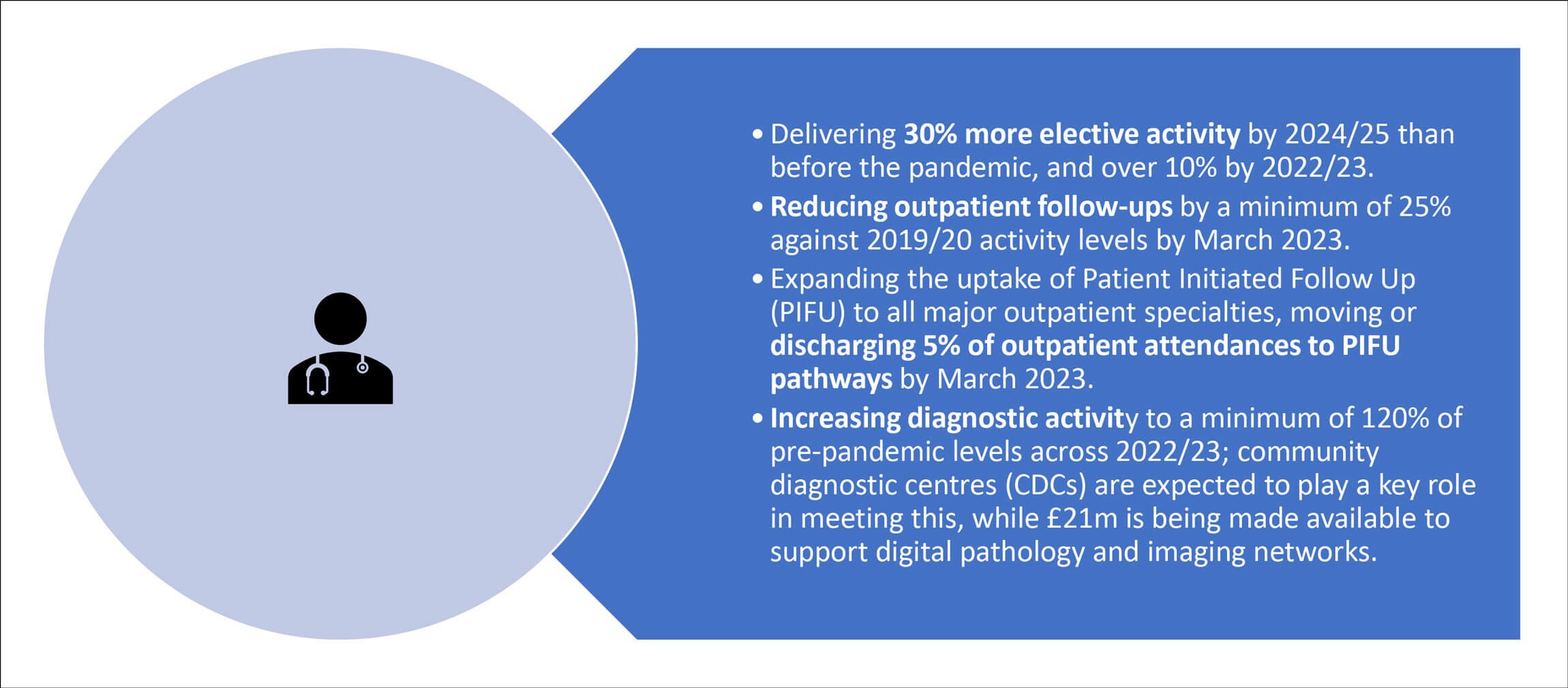

- Deliver around 30% more elective activity by 2024/25 than before the pandemic, over 10% by 2022/23.

Several other targets that will directly impact ophthalmology are summarised in Figure 2. Three strategies will be utilised to tackle the backlog of elective care: expanding community diagnostic centres, increasing surgical capacity through surgical hubs, and improving patient pathways to reduce avoidable delays.

Figure 2: Targets from NHS Planning Guidance 2022-23.

Expanding community diagnostic services

Routine diagnostic appointments postponed during the pandemic have led to a backlog of patients waiting for tests. Community diagnostic centres (CDCs) are seen as an essential part of the overall aim to more clearly separate urgent and elective care, by taking patients requiring diagnostic services away from acute areas. The NHS announced 40 CDCs in October last year, with plans to increase this to at least 100 centres in the community and high street settings over the next three years. It is hoped that focused CDCs will enable the delivery of bundles of tests in a single appointment, enabling faster diagnosis.

One cited case study is the Finchley Memorial CDC, established in Central London in July 2021 and providing MRI, CT and ultrasound scanning, blood testing and ophthalmology services. Having conducted more than 8000 diagnostic tests across five modalities by November 2021, the centre aims to deliver a further 32,000 tests by the end of March 2022, split across eight modalities. The patient journey time through ophthalmology testing averages 40 minutes.

Increasing surgical capacity through surgical hubs

Ophthalmology and orthopaedic patients comprise approximately 22% of those waiting to be admitted to hospital for surgery. Elective surgical hubs, within a hospital as a distinct unit or ringfenced theatre for example, will be expanded across the country. Many are already being piloted to help fast-track the number of planned operations, including cataract removal, hysterectomies and hip and knee replacements.

Expansion of surgical hubs and community diagnostic centres will undoubtedly help bolster the capacity of ophthalmology services. Hubs effectively support high flow cataract surgery. Moorfields Eye Hospital has used surgical hubs to cut the time cataract patients spend in hospital to around 90 minutes. Elsewhere, ‘Super Saturdays’ have expanded capacity.

In terms of improving patient pathways, telephone or video consultations will form a key feature of frontline triage across most specialties. Ongoing development of the NHS e-Referral Service will enable the sharing of images to support clinical teams to undertake more effective triage, while improving patient experience.

Independent minded

The NHS elective recovery plan describes an intention to make greater use of the independent sector to boost capacity [2]. Private independent providers delivered close to half of NHS cataract procedures in England in 2021, markedly up from 11% in 2016 [4]. In a position statement in November 2021, the Royal College of Ophthalmologists called for private providers to ensure equitable access for all patients needing surgery and to rapidly increase access to surgical training in the independent sector [4].

Reduced surgical opportunities, especially of routine cataracts, make it difficult for ophthalmologists to successfully complete training. Moreover, if less complex cataract cases are increasingly referred to the independent sector, this could have significant implications for the financial viability of NHS eyecare units which deliver comprehensive care, including out of hours and subspecialty work.

Consultant Ophthalmologist Imran Rahman, CEO of Community Health and Eyecare Ltd, the largest provider of community-based ophthalmology services in the UK, commented: “Community-based services, which can reduce the burden being faced by the NHS, offer an existing solution that must be fully utilised. There are now 300,000 people waiting at least a year for surgery, a rise of almost 200-fold from before the pandemic. Cataract surgery, for example, has a recommended maximum wait time of 18 weeks but the average wait time has now reached nine months, with some patients waiting as long as two years.”

He said that community-based services offer local solutions to ease the backlog of essential procedures. For example, local eyecare clinics can offer treatment to the 500,000 patients who are currently waiting for ophthalmology services, thus reducing the NHS burden and providing a more convenient local service for patients.

Reducing outpatient follow-ups

The Royal College of Ophthalmologists has also published a briefing on NHS guidance on reducing outpatient follow-ups, including a target to cut outpatient follow-ups by 25% [5]. Potential steps to reduce in-person outpatient appointments include delivering diagnostic services outside of the hospital, offering patient-initiated follow-up appointments where clinically appropriate, and implementing robust discharge guidelines and referral refinement criteria. Ophthalmology as a specialty faces significant challenges in safely reducing outpatient follow-ups in the short term, faced with long backlogs and follow-up appointments often essential to prevent and manage chronic eye diseases.

Medical workforce pressures

More specialty training places for ophthalmology are needed to meet increased patient demand in the future. The NHS plan acknowledges the demand to grow and support the workforce and the need to more systematically train, recruit and retain staff. Health Education England, responsible for long-term workforce planning, education and training of healthcare staff, will merge with NHS England and NHS Improvement. The aim is to deliver a more coordinated approach and better alignment of service, financial and workforce planning, central to recovering elective care. Increasing consultant posts, increasing trainee numbers and actively retaining senior surgeons are all required to maintain capacity [6].

Service redesign across ophthalmology

It is estimated that eye units face a potential 50% increase in cataract surgery workload per week in the post-COVID era, underscoring the need to reset and transform cataract service pathways [7]. Lin et al. propose development of a comprehensive patient-centred care pathway using the principles of value-based healthcare, termed “the cataract integrated practice units”. This involves development of a surgical database that incorporates all aspects of patient need from education to individual follow-up through the cataract journey.

After nine months of curtailed elective cataract surgery, rates of posterior capsular rupture (PCR) increased across all surgeon grades and was not related to case complexity, shown in a single-centre, retrospective note review: PCR rates were 1.67% during the period February 2019 to January 2020, compared with 3.55% during the period January to July 2021. Postoperative cystoid macula oedema rates increased during the COVID-related curtailment and were not related to the proportion of diabetics or increased PCR rates. Study authors highlight the need for more support and guidelines for ophthalmic surgeons of all grades returning to surgery after an extended break, to improve patient safety [8].

High flow cataract surgery

Mixed cataract surgery lists, involving both routine and complex cases, and complex-only lists, benefit from many of the high flow cataract surgery principles. Sunderland Eye Unit has a dedicated complex-sedation list able to complete 8–10 cases by applying high flow principles to every list. Some independent service providers running high flow lists are now including complex cases and may only exclude those needing a general anaesthetic.

Updated guidance from the Royal College of Ophthalmologists recognises that high flow cataract surgery principles are applicable to all but the most highly complex cases and recommends that high flow approaches should be used in all cataract surgery settings [9]. It states that most case complexity is deliverable in stand-alone local anaesthetic day case units. It emphasises that high flow on the day processes can develop only within a whole pathway approach, backed by a strong commitment from provider and commissioner senior leaders.

Immediately sequential bilateral cataract surgery (ISBCS) offers an alternative to delayed sequential bilateral cataract surgery in the right setting and can help to decrease surgical scheduling and follow-up visits.

Implementing a high-volume medical retina virtual clinic utilising a diagnostic hub also has potential to review patients efficiently and safely, and potentially transform the management of patients with medical retina conditions [10].

Timely care of glaucoma patients: backlog of glaucoma patients whose appointments had been deferred and were classified as ‘low risk’

Rapid Glaucoma Assessment Clinics have proven an effective approach to deliver high-throughput clinical assessments for large numbers of ‘low-risk’ glaucoma patients with deferred appointments. A recent evaluation confirmed that these rapid assessment clinics, based on data-driven risk stratification, enable rapid identification of patients thought to be at low risk who may need escalation of care [11].

Of 479 patients attending and assessed, 82.3% were deemed ‘low risk’ and booked for further routine review in the stable monitoring service with a nine-month follow-up interval, with 15% scheduled for further formal assessment within a four-month interval, and 2.7% expedited for formal face-to-face clinic review within two months. Over 10% of ‘low risk’ patients required an immediate escalation in treatment. The authors comment that simple, rapidly-acquired ‘red-flag’ markers of possible harm and risk factors for harm enables identification and treatment of those patients most at risk during the recovery period [11].

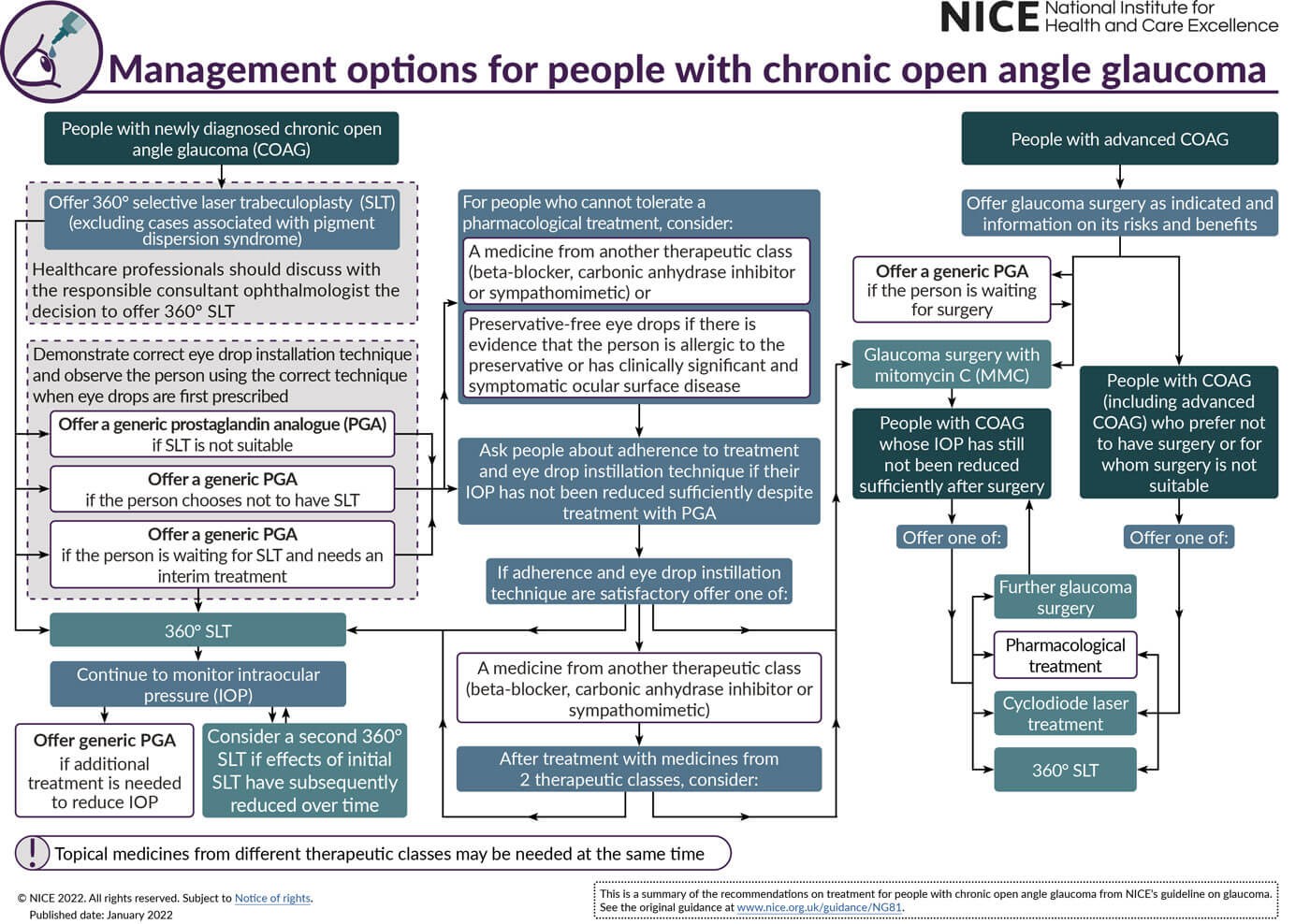

Figure 3. NICE glaucoma guidance, updated January 2022.

The role of 360o selective laser trabeculoplasty

The updated guideline on glaucoma diagnosis and management from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence reflects the new recommendations on selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) as a first-line treatment for ocular hypertension (OHT) and chronic open angle glaucoma (COAG), and clarifies that people with suspected COAG should be offered treatment if they are at risk of visual impairment within their lifetime (Figure 3) [12]. People newly diagnosed with glaucoma (excluding cases associated with pigment dispersion syndrome) and OHT, at risk of visual impairment within their lifetime, should initially be offered SLT treatment rather than eye drops.

Development of an optometrist-delivered SLT service may help address current and future demand for SLT and is expected to benefit the NHS. As Konstantakopoulou et al. observe, successful rollout of an optometrist-delivered service should be preceded by the drafting of national standard training and treatment protocols. Management of glaucoma patients by appropriately trained non-medical professionals could also significantly boost clinic capacity [13].

Paediatric and orthoptic service perspectives

Paediatric ophthalmology suffered significant service loss as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, a specialty considered vulnerable to capacity issues and the consequence of delayed or cancelled appointments. During the initial pandemic peak, the paediatric ophthalmology unit at Alder Hey Children’s Hospital saw outpatient clinic appointments reduced by 87.2%, ophthalmic surgery by 90.9%, outpatient referrals to ophthalmology by 50.2% and ward reviews by 50% [14]. Teleophthalmology solutions, although offering potential, may be difficult to implement in the paediatric population.

A survey of orthoptic service in the UK and Ireland during the interim recovery period (summer 2020) of the COVID-19 pandemic reported that the average backlog of patient appointments had increased to 26 weeks [15]. During the reopening of orthoptic clinics for in-person appointments, teleconsultation remained in frequent use (92%), but with greater risk assessment and triage to identify those requiring in-person appointments.

Expanding workforce capacity and necessary training opportunities

A lack of elective activity during the COVID-19 pandemic meant fewer opportunities for surgical training, with evidence showing that breaks from performing regular surgery impact technical skills and competencies [8]. Expanding workforce capacity makes it easier to provide the necessary training opportunities. To maintain elective care during any future COVID-19 wave, ophthalmologists in training need sufficient opportunities to develop the clinical skills to progress. Poor surgical exposure and difficulty in obtaining adequate cataract surgery experience underscore the competing challenges of service provision and training opportunities [16].

There were an estimated 2.5 ophthalmology and medical ophthalmology consultants per 100,000 population as of March 2021, well short of the estimated 3–3.5 consultants needed to deliver services in hospitals. As well as extending the number of consultant posts, more Staff, Associate Specialist and Specialty (SAS) doctors and specialty registrars are needed to deliver ophthalmology services [16].

The House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee believes that while prioritisation of the elective backlog is understandable, a “new targets culture” risks unintended consequences, including compromising the quality and safety of patient care. It asserts that workforce shortages are a key limiting factor on success in tackling the backlog, with shortages in most specialties. “We continue to believe that giving hope to NHS staff that the appropriate number of new staff will be trained in the future is the biggest single measure the Government can take to gain the confidence of frontline staff that it has a grip of this problem,” [17].

References

1. NHS Digital. Hospital Outpatient Activity 2020–21. 2021:

https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/

publications/statistical/hospital

-outpatient-activity/2020-21

(Last accessed March 2022).

2. NHS England. Delivery plan for tackling the COVID-19 backlog of elective care:

https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/

wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2022/02/C1466

-delivery-plan-for-tackling-the-covid

-19-backlog-of-elective-care.pdf

(Last accessed March 2022).

3. National Audit Office. NHS backlogs and waiting times in England:

https://www.nao.org.uk/report/nhs

-backlogs-and-waiting-times-in-england/

(Last accessed March 2022).

4. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Three Steps to sustainable patient care: the RCOphth view on the independent sector and the delivery of NHS cataract surgery:

https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/

wp-content/uploads/2021/11/

RCOphth-Three-Steps-to-sustainable

-patient-care.pdf

(Last accessed March 2022).

5. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Implementing NHS guidance on reducing outpatient follow-ups: briefing:

https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/

wp-content/uploads/2022/02/

RCOphth-briefing-on-reducing

-outpatient-follow-ups.pdf

(Last accessed March 2022).

6. Magennis P, Begley A, Dhariwal DK, et al. Oral and maxillofacial surgery (OMFS) consultant workforce in the UK: reducing consultant numbers resulting from recruitment issues, pension pressures, changing job-plans, and demographics when combined with the COVID backlog in elective surgery, requires urgent action. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2022;60(1):14-9.

7. Lin PF, Naveed H, Eleftheriadou M, et al. Cataract service redesign in the post-COVID-19 era. Br J Ophthalmol 2021;105(6):745-50.

8. Theodoraki K, Naderi K, Lam CFJ, et al. Impact of cessation of regular cataract surgery during the COVID pandemic on the rates of posterior capsular rupture and post-operative cystoid macular oedema. Eye (Lond) 2022;3:1-6.

9. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. High flow cataract surgery. Ophthalmic Services Document. Version 2.0:

https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/

wp-content/uploads/2022/02/

High-Flow-Cataract-Surgery_V2.pdf

(Last accessed March 2022).

10. Hanumunthadu D, Adan K, Tinkler K, et al. Outcomes following implementation of a high-volume medical retina virtual clinic utilising a diagnostic hub during COVID-19. Eye (Lond) 2022;36(3):627-33.

11. Jayaram H, Baneke AJ, Adesanya J, Gazzard G. Managing risk in the face of adversity: design and outcomes of rapid glaucoma assessment clinics during a pandemic recovery. Eye (Lond) 2021;10:1-5.

12. NICE. Glaucoma: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline ng81:

https://www.nice.org.uk/

guidance/NG81/resources/

glaucoma-diagnosis-and-management

-pdf-1837689655237

(Last accessed March 2022).

13. Konstantakopoulou E, Jones L, Nathwani N, Gazzard G. Selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) performed by optometrists-enablers and barriers to a shift in service delivery. Eye (Lond) 2021;13:1-7.

14. Wood M, Gray J, Raj A, et al. The impact of the first peak of the COVID-19 pandemic on a paediatric ophthalmology service in the United Kingdom: experience from Alder Hey Children’s Hospital. Br Ir Orthopt J 2021;17(1):56-61.

15. Rowe FJ, Hepworth LR, Howard C. Orthoptic service survey in the UK and Ireland during the interim recovery period (summer 2020) of the COVID-19 pandemic. Strabismus 2021;29(4):252-66.

16. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Response from The Royal College of Ophthalmologists (RCOphth) to the HEE Strategic Framework Call for Evidence:

https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/

wp-content/uploads/2021/09/

RCOphth-response-to-HEE

-Strategic-Framework-Call-for

-Evidence-6-Sept-final-1.pdf

(Last accessed March 2022).

17. The House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee. Clearing the backlog caused by the pandemic. HC 599:

https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5802/

cmselect/cmhealth/599/report.html

(Last accessed March 2022).

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME