Can you give us a brief overview of the organisation and its hope for the future?

Orbis International is a global non-governmental organisation (NGO) which is dedicated to the prevention of blindness. We’ve now been going since 1982. We’re very focused on work in a relatively small number of countries in the world, about 19, but we tend to work for a long period of time and really in-depth because that’s what we’ve got to do. These countries are in real need and we know are going to be receptive to what we can do with them.

We work very much in partnership with them and hope that one day, with the right support and resources, they will be able to serve more people in their own population and I think that’s a very real possibility. I say we work in a relatively small number of countries, but I believe we have a really big impact. Last year, for example, thanks to UK supporters, we delivered around 10 million medical and optical treatments including antibiotics for trachoma and surgeries etc… Over the last four years across India and Bangladesh we’ve provided 6.1 million screenings to children to find those with visual problems. Most of those had refractive error and needed spectacles and we issued them with the spectacles they required.

What are the most common conditions faced around the world?

Ninety percent of people with vision loss live in low- and middle-income countries, so there’s a huge number of people who require our support. The most common causes of blindness and vision loss in the world are cataract and refractive error – just a simple need for glasses, such a simple thing that people can’t always access – and a cataract operation just takes 15 minutes! It is an extraordinary thing that there are still tens of millions of people in the world who are blind from these conditions. As a teaching organisation, we work with governments to develop their own health systems. We always work very closely with governments to make sure we work within their health programs and health strategies, and we have found this to be a successful method of working throughout the world. This may start off in a very small way in a country, but it is important to develop relationships that are very substantial, both within government but also within national organisations.

The epidemiology in one country will be different from another, it could be inherited diseases, cataracts or neglected tropical diseases, but often the conditions are treatable and very simply so. For example, we are working with the International Trachoma Initiative to eliminate trachoma in the world and I think we’ve got a real chance of doing that within the next 10 years and making it a major success like smallpox.

Children receiving eye exams at Orbis supported vision centres and schools in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.

What are the challenges faced in treating refugees?

This is a very good question to ask because refugees are a challenging group of people to treat. The very first thing I think we need to address about working with refugees is to make sure that it is stable and secure, not only for them, but also for the volunteers and the doctors and nurses and the ancillary people we send, that they are going to be in a safe environment, so security is really important in the approach to working with refugees. We tend not to do the emergency work, the sort of work that Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) do, for example, who do go into very dangerous zones. By the time we get there it’s normally stabilised and that’s quite important, but working with refugees, there are important considerations to be made and be respectful of. Many of these refugees are gathered together in cultural groups and sadly many times that’s why they’ve been persecuted and expelled from their home. And there are medical issues to consider. So, a lot of work needs to go in initially to find out where we can help.

The other issue is to find partners we can work with in those countries and we’re beginning to do that now. We’ve started off by working with the Rohingya community in southeast Bangladesh in Cox’s Bazar, thanks to funding from the Qatar Fund for Development. There are around 900,000 people there. What we found when we first went in, in 2018, was that 30% of these refugees had eye problems and that’s a gargantuan number in comparison to the number you would find in the in the UK or in America. What this taught me was that most of these conditions were completely treatable or avoidable and, secondly, the treatment for them is very straightforward, not expensive, and relatively easy to do once you’ve got the resources.

So, working with partners in affected countries, identifying who those partners are, and forming those friendships and professional relationships is really important. Then you can start working together, once you’ve identified the model that will work in that particular country, which will be different in different countries, and then you can start to expand that model, we can fundraise for that model and really start making a difference.

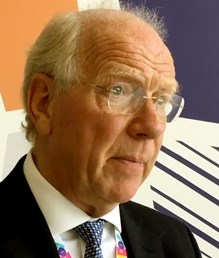

Robert Walters volunteering with Orbis, 2008.

What can governments do to contribute to the aim of eradicating avoidable blindness?

I think there are many ways of looking at that. I think the first point is that in developed countries those governments can provide both expertise and money to underdeveloped countries, where the most need is. Organisations such as the Department For International Development (now the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office) will provide funds for example, it set aside £50 million for the treatment of neglected tropical diseases, which would include eye diseases.

Regarding governments in the countries where we work, there’s a great deal they can do, but don’t always have the necessary resources and their GDP is very low. We work with governments to establish sustainable healthcare models. Organisations like Orbis need to approach governments in an understanding and culturally sensitive way. To say that we recognise that you have a need and how can we help you to strengthen and develop your eye health services. We would never want to go in and say we know all the answers because we don’t, but they know many of the answers and we know others. Governments have set budgets and one of our jobs in terms of advocacy is to advocate for the causes we believe in and try to convince those governments to spend a little bit more money of their budget to have a greater impact in a certain area.

How can ophthalmologists get involved?

An ophthalmologist can get involved in charitable work overseas and there are many ways they can do that. Organisations like Orbis have what we call a volunteer faculty, which are professional people of all levels, like ophthalmologists, biomechanical engineers, nurses and administrators. You need a whole team approach as each would be useless on their own. UK ophthalmologists can also get involved with exchange programs with countries of need, by offering fellowships or having twinning programs with other countries like the VISION 2020 LINKs Programme.

One of the first people I ever met was a man called Professor El Hadi Ahmed El Sheikh, who was a professor in the Sudan and Khartoum. I first went as a volunteer and we developed a good friendship and we corresponded as to how we could help each other. He taught me a lot and I would send him equipment and bits and bobs that he required as you could not get them where he was. I think even on a one-to-one basis you can develop a meaningful and productive relationship with eye surgeons, nurses and other professionals elsewhere in the world. I would encourage all ophthalmologists young and old to spread their wings because it’s an incredibly satisfying, enjoyable and educational experience.