Is there a crisis in ophthalmic education? The British Undergraduate Ophthalmology Society surveyed medical students and junior doctors to evaluate current ophthalmology teaching across medical schools in the UK.

British medicals schools are currently not obligated to include ophthalmology within their undergraduate curriculum [1]. Although ophthalmology is taught in some form at medical school, the lack of national guidance has amplified the discrepancies in teaching between the medical schools [2]. Undergraduate medical education was overhauled following the publication of Tomorrow’s Doctors by the General Medical Council (GMC) [3].

The drive to unpack the overcrowded curriculum to one that encompasses fundamental and clinically relevant knowledge and skills, and focused on common conditions, has led to small niche specialties such as ophthalmology being marginalised [2,3]. The crisis in ophthalmic education is not specific to the UK but has been recognised internationally [4,5,6].

The eyes are often affected by systemic disease and so ophthalmology has great relevance in many specialties, including diabetes and endocrinology, neurology, neurosurgery, otorhinolaryngology, rheumatology and cardiology. Patients with an acute eye problem most often present to either general practice (GP) or accident and emergency (A&E) in the first instance. Eye complaints account for 2-3% of all GP and 1.5-6% of all A&E consultations [7]. Empowering non-specialists with basic ophthalmic knowledge could potentially allow common eye complaints to be treated in A&E or in the community, thereby helping to reduce patient anxiety, allow care to be delivered closer to home and lessen the workload for specialists, whilst allowing them to address the more serious ocular pathologies. Most importantly, examination of the visual system constitutes part of the full physical examination [1]. Therefore, all doctors graduating from medical school must have adequate ophthalmic knowledge.

Presently there is a poverty of published data examining trainee perceptions of undergraduate ophthalmology teaching. The aim of the study was to evaluate current ophthalmology teaching in the UK from the medical student and junior doctor’s perspective.

Materials / subjects and methods

An online anonymised SurveyMonkey© questionnaire targeting medical students (third year or above) and foundation year doctors, was made available between April and September 2014. An invitation to complete the survey was sent out by email via the British Undergraduate Ophthalmology Society’s (BUOS) mailing list (paid members and those subscribed to emails) and the BUOS medical school representatives utilising their respective local mailing lists. The survey was also advertised on the BUOS website and social media (Facebook and Twitter). Reminders were sent out halfway through the study period and one week prior to the closing date. An incentive (Amazon / iTune vouchers) for completing the survey was advertised to maximise response.

The questionnaire assessed perceptions regarding undergraduate ophthalmology teaching in four areas – delivery method, content, duration and effectiveness. The survey consisted of 35 questions in three sections, designed to take approximately 10-15 minutes. The first section gathered demographic data. The second section was subdivided with questions focusing on the type(s) of teaching methodology utilised (didactic lectured based teaching, small group teaching (SGT) and problem-based learning (PBL)) and the experiences from them; clinical skills taught and learned; and clinical attachments (excluding electives and student selected study modules). The final section contained open questions regarding the overall perception of their ophthalmology teaching, whether students felt enough time was allocated to the field, and if they felt confident in their ophthalmic knowledge.

Responses were analysed independently by three authors. Statistical analysis was undertaken using the software provided on SurveyMonkey© and Microsoft Excel 2016. Ethical approval was not required for this study.

Results

Demographics

In total, 1070 responses were obtained; of which 98 incomplete and 37 duplicated entries were excluded, thus leaving 935 responses for analysis. Responses were obtained from students from all 32 UK medical schools (Table 1). Twenty-three percent were from third year students, 31% from fourth year students and 36% from final year medical students. Durham and St Andrews University were excluded from the study as they only teach pre-clinical medicine. A small proportion of the respondents were foundation year doctors (n=84, 9%) and were grouped into the undergraduate medical school from which they graduated.

Table 1: Proportion of responses from each medical school.

Medical school: University of Aberdeen

Proportion n (%): 45 (4.8)

Medical school: Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry,

Queen Mary’s, University of London

Proportion n (%): 24 (2.6)

Medical school: University of Birmingham

Proportion n (%): 22 (2.4)

Medical school: Brighton and Sussex Medical School

Proportion n (%): 37 (4.0)

Medical school: University of Bristol

Proportion n (%): 3 (0.3)

Medical school: University of Cambridge

Proportion n (%): 21 (2.2)

Medical school: Cardiff University

Proportion n (%): 19 (2.0)

Medical school: University of Exeter

Proportion n (%): 10 (1.1)

Medical school: University of Dundee

Proportion n (%): 35 (3.7)

Medical school: University of Durham

Proportion n (%): 0

Medical school: University of Edinburgh

Proportion n (%): 30 (3.2)

Medical school: University of Glasgow

Proportion n (%): 70 (7.5)

Medical school: Hull York Medical School

Proportion n (%): 37 (4.0)

Medical school: Imperial College School of Medicine

Proportion n (%): 35 (3.7)

Medical school: Keele University

Proportion n (%): 5 (0.5)

Medical school: King’s College London School of Medicine

Proportion n (%): 24 (2.6)

Medical school: Lancaster University

Proportion n (%): 7 (0.7)

Medical school: University of Leeds

Proportion n (%): 57 (6.1)

Medical school: University of Leicester

Proportion n (%): 17 (1.8)

Medical school: University of Liverpool

Proportion n (%): 88 (9.4)

Medical school: University of Manchester

Proportion n (%): 25 (2.7)

Medical school: Newcastle University

Proportion n (%): 30 (3.2)

Medical school: University of East Anglia

Proportion n (%): 46 (4.9)

Medical school: University of Nottingham

Proportion n (%): 44 (4.7)

Medical school: University of Oxford

Proportion n (%): 17 (1.8)

Medical school: Plymouth University Peninsula Schools of Medicine and Dentistry

Proportion n (%): 14 (1.5)

Medical school: Queen’s University Belfast

Proportion n (%): 9 (1.0)

Medical school: University of Sheffield

Proportion n (%): 45 (4.8)

Medical school: University of Southampton

Proportion n (%): 13 (1.4)

Medical school: University of St Andrews

Proportion n (%): 0

Medical school: St George’s, University of London

Proportion n (%): 16 (1.7)

Medical school: Swansea University

Proportion n (%): 26 (2.8)

Medical school: University College London

Proportion n (%): 46 (4.9)

Medical school: University of Warwick

Proportion n (%): 18 (1.9)

Total: 935

Ophthalmology teaching

Ophthalmology was incorporated into the medical curricula in some form in all 32 medical schools. Thirty-one schools provided teaching in didactic lecture form, 31 schools provided small group teaching, whilst 14 schools provided PBL teaching. All 32 schools provided clinical skills teaching and a clinical placement in ophthalmology.

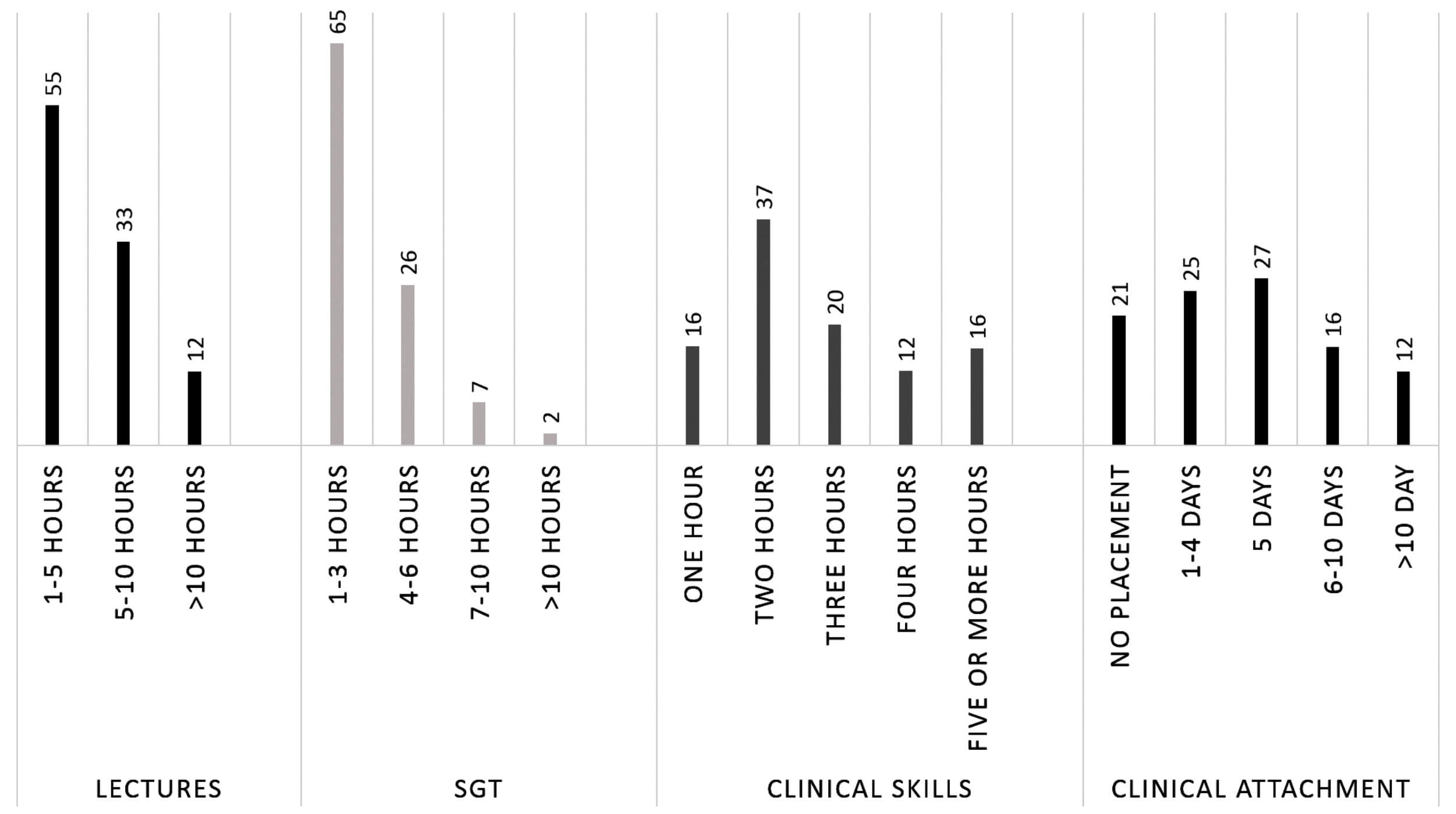

Figure 1: Time allotted to various teaching modalities.

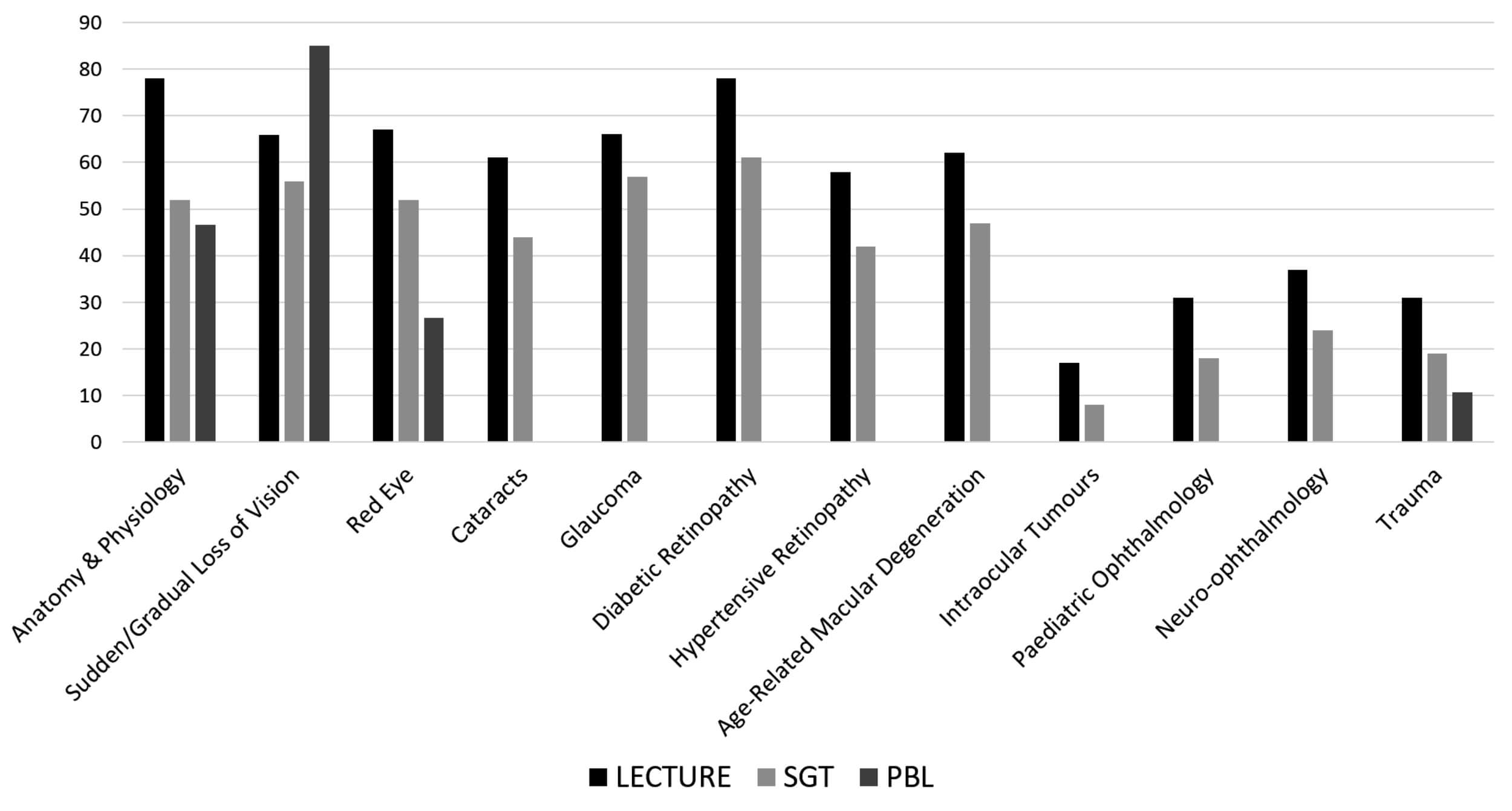

According to the medical students, teaching was delivered via lectures (98%), SGT (69%), PBL (62%), clinical skills (88%) and a clinical attachment (68%). The range of total time spent in each of the respective modalities utilised are summarised in Figure 1. The topics taught and methodology used by medical schools are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Topics covered during teaching.

Ophthalmology was taught in the form of didactic lectures in 31 of 32 medical schools. Of those students affirming lecture-based teaching (n= 920), 55% received a total of one to five hours of lecturing. Sixty-eight percent of students (n=616) thought the range of topics covered in lectures was adequate. However, when asked about the amount of time dedicated to lectures, over half of the respondents (59%) stated they would prefer more lectures.

Similarly, ophthalmology teaching was delivered in small group teaching at 31 medical schools. Of the students taught in small groups, 69% (n=534) felt the topics covered were ample but 67% (n=550) felt the time allocated was not adequate.

The 14 medical schools which incorporated ophthalmology teaching into PBL either had at least one stand-alone scenario dedicated to ophthalmology (54%, n=315), or amalgamated with other specialties such as neurology and endocrinology (46%, n=265). PBL sessions dedicated to ophthalmology were delivered once (31%, n=159), twice (17%, n=87), thrice (11%, n=55), or four or more times (5%, n=29). When included with other systems, ophthalmology was covered once (27%, n=137), twice (16%, n=85), thrice (6% n=32) or four or more times (4%, n=20). Sixty-two percent of students felt that the topics covered were adequate.

Table 2: Percentage of clinical skills taught in the undergraduate medical curricula of UK medical schools.

Clinical Skill Taught: Direct ophthalmoscopy

Percentage: 79

Clinical Skill Taught: Indirect ophthalmoscopy

Percentage: 22

Clinical Skill Taught: Pupil examination

Percentage: 62

Clinical Skill Taught: Instilling eye drops

Percentage: 19

Clinical Skill Taught: Intraocular pressure measurement

Percentage: 6

Clinical Skill Taught: Confrontational visual fields

Percentage: 76

Clinical Skill Taught: Slit-lamp examination

Percentage: 22

Clinical Skill Taught: Visual acuity measurement

Percentage: 48

Clinical Skill Taught: Colour vision

Percentage: <1

Clinical Skill Taught: Ocular motility

Percentage: 1

Ophthalmic clinical skills were included within the undergraduate curricula at all 32 medical schools. The clinical skills taught are summarised in Table 2; the commonest clinical skills taught included direct ophthalmoscopy, visual field examination, visual acuity and pupil examination. Clinical skills were taught using more than one modality, most commonly small group teaching (65%, n=611). This took place either in a simulation lab (47%, n=389) or at the bedside or in clinic (43%, n=353). The overwhelming majority of students felt that the methods of teaching were adequate (99%). However, 53% (n=438) stated they would like more time to practise. In relation to time allocated to clinical skills teaching, 30% (n=245) felt more teaching was necessary. Approximately half of respondents (47%, n=391) who had formal clinical skills teaching did not feel confident in examining the eyes and visual system.

Clinical attachment

All 32 medical schools offered a clinical attachment in ophthalmology excluding electives and student selected components. The most common duration of a clinical attachment length was five days, and half of the respondents (50%, n=361) felt more time should have been allocated to such learning opportunities. During their clinical attachment 32% (n=235) of students did not receive any formal teaching. Of those students who did receive teaching, only 29% (n=2120 felt it was satisfactory.

General consensus

Overall, half (52%, n=427) of all senior medical students do not feel confident in their ophthalmic knowledge and would like more time dedicated to ophthalmology. Seventy-five percent (n=609) felt their respective medical schools’ methodology in delivering ophthalmology was inadequate.

Foundation year doctor experience

Thirty-seven percent of foundation doctors are not confident in examining the visual system and 39% feel they have inadequate knowledge in ophthalmology. Over half of all junior doctors (56%) would have liked more ophthalmology teaching in preparation for starting work.

Discussion

Innovative basic and clinical research over the past two decades has revolutionised the practice of ophthalmology; new therapies and investigative modalities have led to a significant rise in demand for eye care. Of the 82.1 million outpatient consultations, ophthalmology has the second highest number of attendances constituting 8.3% of all NHS appointments [8]. The past 10 years has seen an increase of approximately two million more eye consultations [8]. With an ageing population and increasing obesity associated illness, the pressure will increase on the already stretched services.

Despite the increasing demands, ophthalmic education has deteriorated over recent years – globally [2,4,5,6]. This survey of students and newly qualified doctors illustrates a worrying recognition of lack of training in ophthalmology which is not replicated in any other specialty. The results echo what previous studies have highlighted; curtailing of ophthalmology teaching and lack of adequate exposure is producing a significant number of doctors hesitant in dealing with eye complaints [9]. Doctors must be able to examine the eye and interpret their findings in order to diagnose and treat, as well as being able to make appropriate referrals and seek specialist intervention in a timely manner [9,10,11]. Inability to do this could not only lead to sight or life-threatening consequences but have medico-legal implications [12].

Furthermore, if an aspiration of government policy is to move healthcare into the community then general practitioners along with optometrists will play an integral role in delivering primary eye care. These doctors will need to be proficient and confident in managing eye problems and this will only be possible by providing the appropriate foundations at an undergraduate level.

This study is not without its limitations. Primarily, this survey is not a snapshot of teaching at an exact time point and this is reflected in the diversity in responses from students within the same schools. Whilst there should be no reason to question the honesty in individual response, given that this was an independent anonymous survey, the variation and potentially conflicting results reflect the evolution of curriculum at individual schools. Thus, had analysis been undertaken collectively and not broken down by medical school, then results would have been far more negative. Many individual responses centred around students not having the same opportunity as their peers and missing out on ophthalmology teaching at the same school. However, student attendance and engagement will also affect the results, as ophthalmology is perceived to be less important compared to other sub-specialties such as cardiology or respiratory medicine. As ophthalmology tends to be less heavily weighted in final examinations students are willing to risk not studying it in depth and to concentrate on other material.

Despite the limitations of such a survey, in particular, inclusion of students who have not yet had all their ophthalmology teaching, answers affected by recall bias and excluding questions related to assessments, the survey has raised a number of important issues. As highlighted by Albert and Bartley [13], instead of watching the decline in ophthalmology education we should take the initiative to overcome this crisis. The survey suggests medical schools are making efforts to include ophthalmology within the curriculum and ophthalmologists should take an active role within medical school teaching faculties and guide those designing the curriculum in terms of what all students must know and how best this can be delivered [14].

Additionally, in a clinical setting, students must be welcomed into the department and given a basic overview, many students in this survey commented they felt out of their depth on their attachment.

Although three-quarters of students in our study population would prefer more time allocated to ophthalmology, medical schools are struggling to strike the balance. We must work towards integrating ophthalmology teaching within other specialties such as general practice, emergency medicine, neurology and diabetes and endocrinology. Students must be encouraged to take responsibility for their own learning and guided to cover vital topics by utilising other teaching modalities such as computer assisted learning (CAL) packages, online revision resources and extracurricular courses. In the UK, only seven schools required a pass in ophthalmology to complete the year [15].

It has been well established, competency based assessments yield results therefore students on an ophthalmology placement should have compulsory outcome specific assessments [13]. These outcomes should reflect the skills needed in general practice or A&E, such as taking an ophthalmic history, measuring visual acuity, direct ophthalmoscopy and basic anterior segment assessment [16].

In the absence of a national core curriculum for ophthalmology, there is variation in ophthalmology teaching across the UK where medicals schools are left to ascertain what is necessary. Although the Royal College of Ophthalmologists has provided some recommendations, the GMC must stipulate guidance for medical schools to ensure uniformity in baseline ophthalmic knowledge upon graduation. Keeping in mind the impact of the dwindling place of ophthalmology education at medical school, a greater effort must be made both at undergraduate and foundation level training to address this serious issue which is affecting the quality and efficiency of service delivery across the NHS.

References

1. GMC. General Medical Council. Tomorrow’s Doctors: Outcomes and standards for undergraduate medical education. London. London: GMC 2009.

2. Baylis O, Murray PI, Dayan M. Undergraduate ophthalmology education - A survey of UK medical schools. Medical Teacher 2011;33:468-71.

3. GMC. General Medical Council. Tomorrow’s Doctors: Recommendations on undergraduate medical education. London: GMC. 1993.

4. Noble J, Somal K, Gill HS, Lam WC. An analysis of undergraduate ophthalmology training in Canada. Can J Ophthalmol 2009;44:513-8.

5. Shah M, Knoch D, Waxman E. The state of ophthalmology medical student education in the United States and Canada, 2012 through 2013. Ophthalmology 2014;121:1160-3.

6. Fan JC, Sherwin T, McGhee CN. Teaching of ophthalmology in undergraduate curricula: a survey of Australasian and Asian medical schools. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2007;35:310-7.

7. The College of Optometrists and The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Commissioning better eye care

https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/

wp-content/uploads/2014/

12/urgent-eye-care-template

-25-11-13-2013-_PROF_264.pdf

Last accessed September 2019.

8. Health and Social Care Information. Hospital Episode Statistics: Hospital Outpatient Activity – 2013-14. 2015

https://digital.nhs.uk/

data-and-information/publications/

statistical/hospital-outpatient-activity/

hospital-outpatient-activity-2013-14

Last accessed September 2019.

9. Statham MO, Sharma A, Pane AR. Misdiagnosis of acute eye diseases by primary health care providers: incidence and implications. Med J Aust 2008;189:402-4.

10. Clarkson JG. Training in ophthalmology is critical for all physicians. Arch Ophthalmol 2003;121:1327.

11. Office UFP. The UK Foundation Programme Curriculum. 2010.

12. Sheldrick JH, Vernon SA, Wilson A. Study of diagnostic accord between general practitioners and an ophthalmologist. Br Med J 2002;304:1096-8.

13. Albert DM, Bartley GB. A Proposal to Improve Ophthalmic Education in Medical Schools. Ophthalmology 2014;121:1157-8.

14. Mottow-Lippa L. Ophthalmology in the medical school curriculum: reestablishing our value and effecting change. Ophthalmology 2009;116:1235-6.

15. Welch S, Eckstein M. Ophthalmology teaching in the medical schools: a survey in the UK. Br J Ophthalmol 2011;95:748-9.

16. Yusuf IH, Salmon JF, Patel CK. Direct ophthalmoscopy should be taught to undergraduate medical students—yes. Eye 2015;29:987-9.

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.

Acknowledgements

This study was undertaken as a joint collaboration between the British Undergraduate Ophthalmology Society and the Education Committee of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists. The authors would like to thank all BUOS representatives in publicising the survey. The authors would also like to express gratitude to Mark Batterburry for his guidance and initial advice on starting this project. No research funding was granted for this project.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME