Using some captivating artwork, Iheukwumere Duru describes key features of pigment dispersion syndrome.

Pigmentary dispersion syndrome (PDS) leads to pigmentary glaucoma (PG) in approximately 35-50% of patients with the condition [1]. PG is the leading cause of non-traumatic blindness in the young adult population between 20 and 40 years of age [2]. As such, it is important for ophthalmic trainees and healthcare professionals alike to be able to identify key clinical features seen in PDS, in order to quickly diagnose this condition, preventing the insidious onset of glaucoma and thus optimising patient care.

What is pigment dispersion syndrome?

PDS is a bilateral ocular disorder, in which pigmented cells (melanin granules) [3] from the posterior surface of the iris are spontaneously released and deposited on structures in both the anterior and posterior chambers. The deposition of these iris pigment cells on the trabecular meshwork (TM) result in its blockage. This blocks the conventional aqueous humor pathway [4] consequently, patients are prone to developing raised intraocular pressures resulting in ocular hypertension or worse, pigmentary glaucoma, a secondary open angle glaucoma seen in 35-50% of patients with PDS [1].

How does PDS present?

Patients with PDS may complain of blurred vision or haloes, particularly after exercise [5]. Patients who present late may have visual field defects in keeping with progression to glaucoma.

Why is pigment released?

Iris pigment is released when the mid-peripheral region of the iris bows posteriorly. This results in the apposition and subsequent rubbing of the iris to the lens zonules. This close apposition between the iris and the lens zonules creates a ‘one-way flow system’, in which aqueous humor travels from the posterior chamber to the anterior chamber but is unable to travel backwards. This configuration can also be described as a ‘reverse pupillary block’. This increases the pressure in the anterior chamber which further contributes to the posterior bowing of the iris onto the lens zonules.

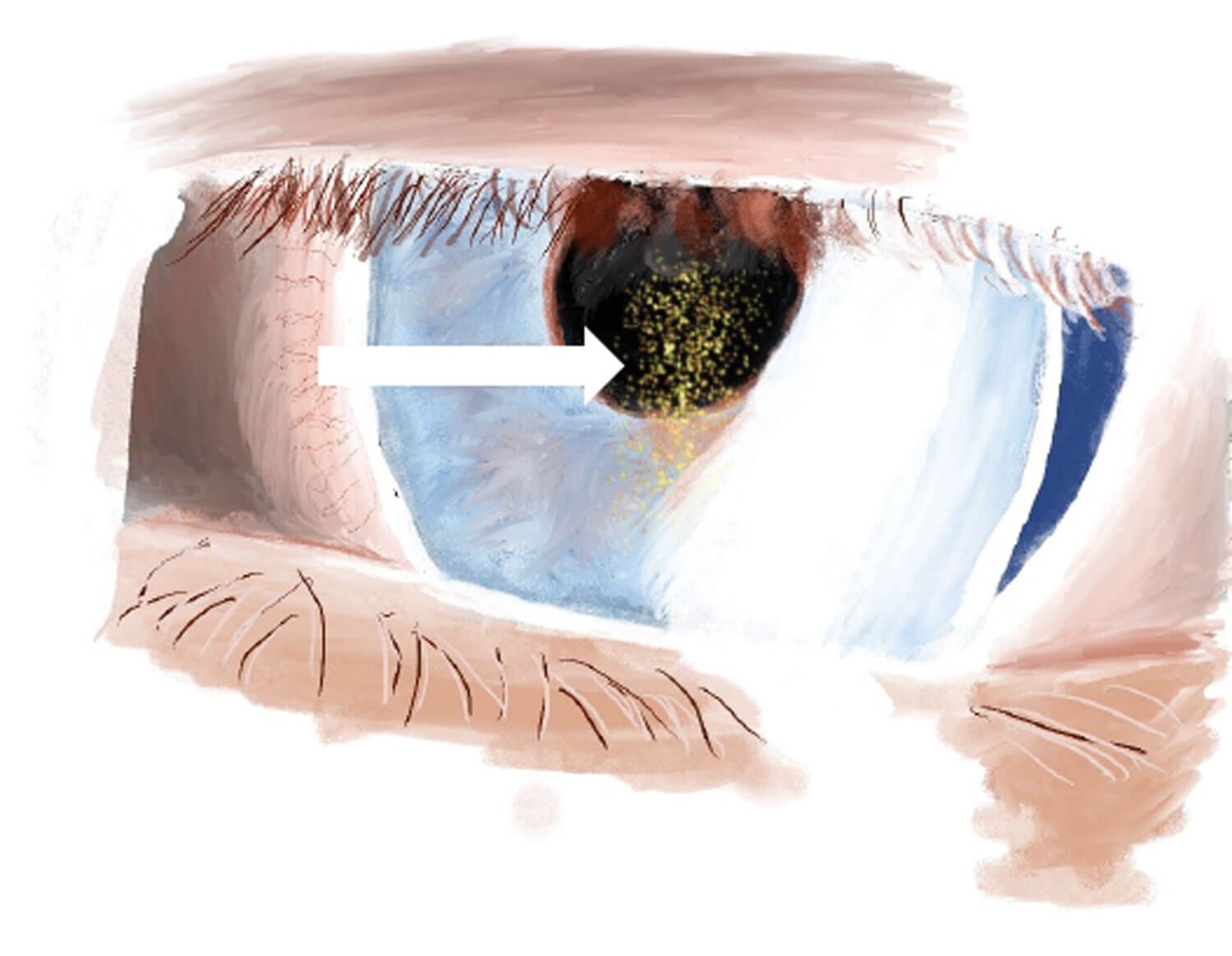

Figure 1: Krukenberg spindles are centrally located pigment cells on the corneal endothelium which display a vertical orientation. They are transported by convective currents within the aqueous humor. These cells are distributed on both the extra-endothelial layer and intra-endothelial layer into which they are phagocytosed. Due to their small size, the patient’s vision is generally not affected [3]. The central vertical orientation of Krukenberg spindles is what differentiates them from other melanin pigment depositions, which are more diffuse. However, the absence of this sign does not rule out PDS [7,8].

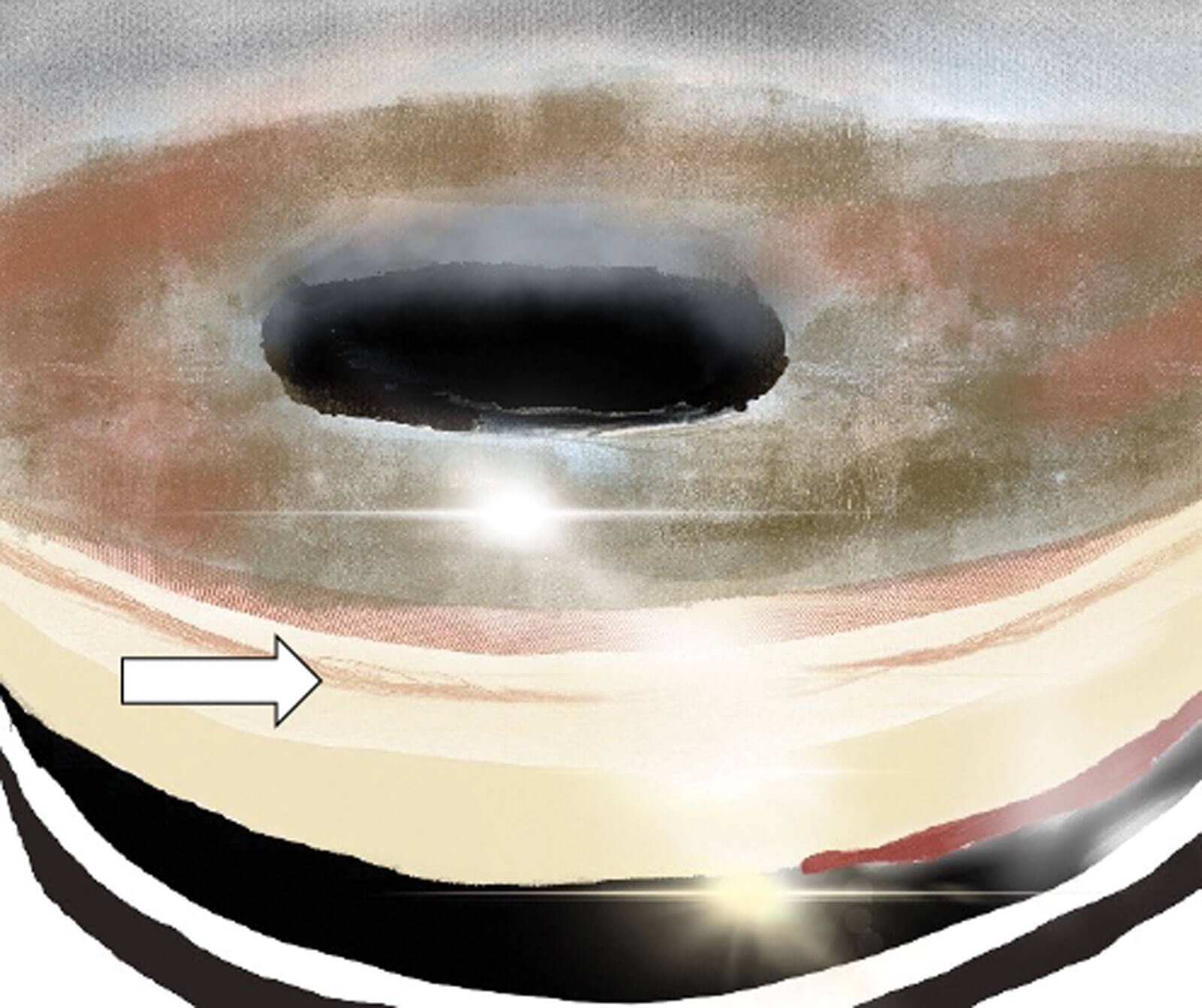

Figure 2: Gonioscopy showing pigment accumulation in the trabecular meshwork (TM) [9]. This pigment is distributed 360 degrees on the TM compared to pseudoexfoliation syndrome (PEX) in which the pigment is mainly deposited inferiorly on the TM.

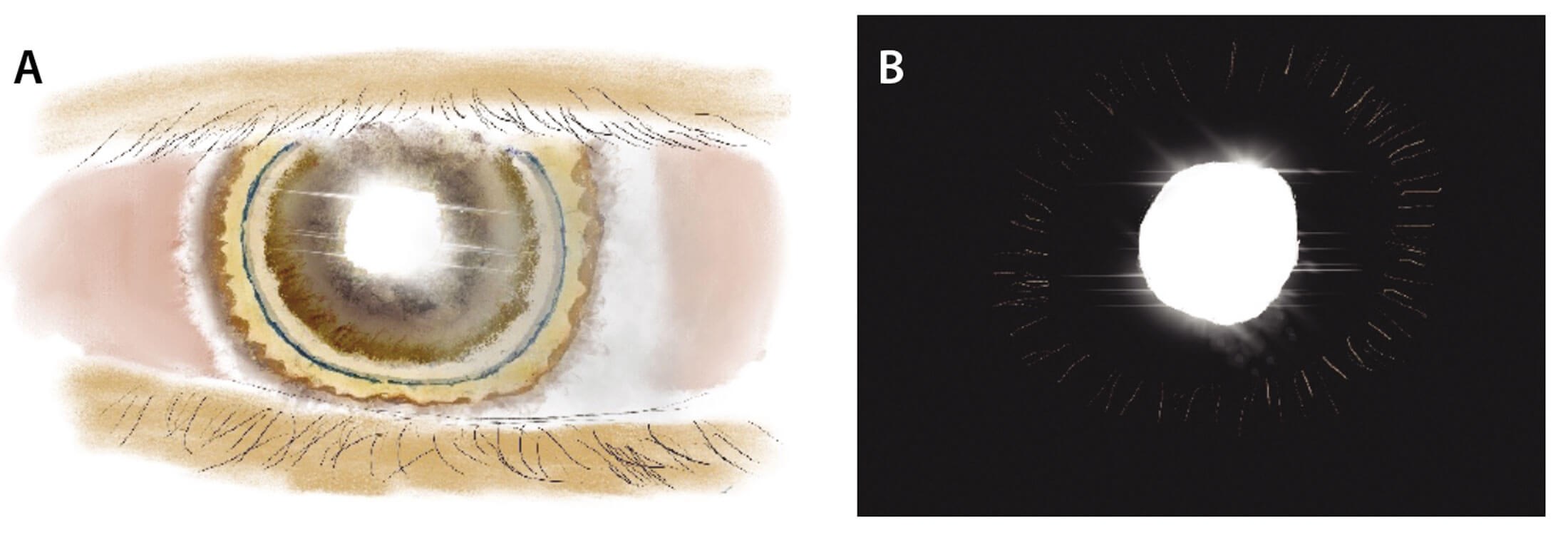

Figure 3: A&B: Mid-peripheral iris trans-illumination defect [5,10]. This is seen in approximately 86% of patients with PDS [5]; C: Iris atrophy showing diffuse iris trans-illumination defect. It is important to differentiate the typical mid-peripheral iris trans-illumination defects seen in A&B from blotchy iris defects which can be seen in light irises or secondary to iris atrophy – C [5,11].

What clinical features should we look out for?

PDS usually presents with a triad of clinical features. From anterior to posterior, these are:

- Krukenberg spindles seen on the corneal endothelium – see Figure 1

- A 360-degree accumulation of pigment on the trabecular meshwork (TM) – see Figure 2

- Mid-peripheral trans-illumination defects of the iris, which are arranged in a radial fashion – see Figure 3.

Pigment deposition is not restricted to the TM and can thus be deposited in other anterior segment structures. As such, other signs to look out for are Scheie’s lines where pigment is deposited on the posterior lens surface at the vitreo-lens junction in the ligament of Weiger. Pigment can also be deposited on other anterior segment structures such as schwalbe’s line, the anterior iris surface causing heterochromia, anterior lens capsule and even in filtration blebs [6].

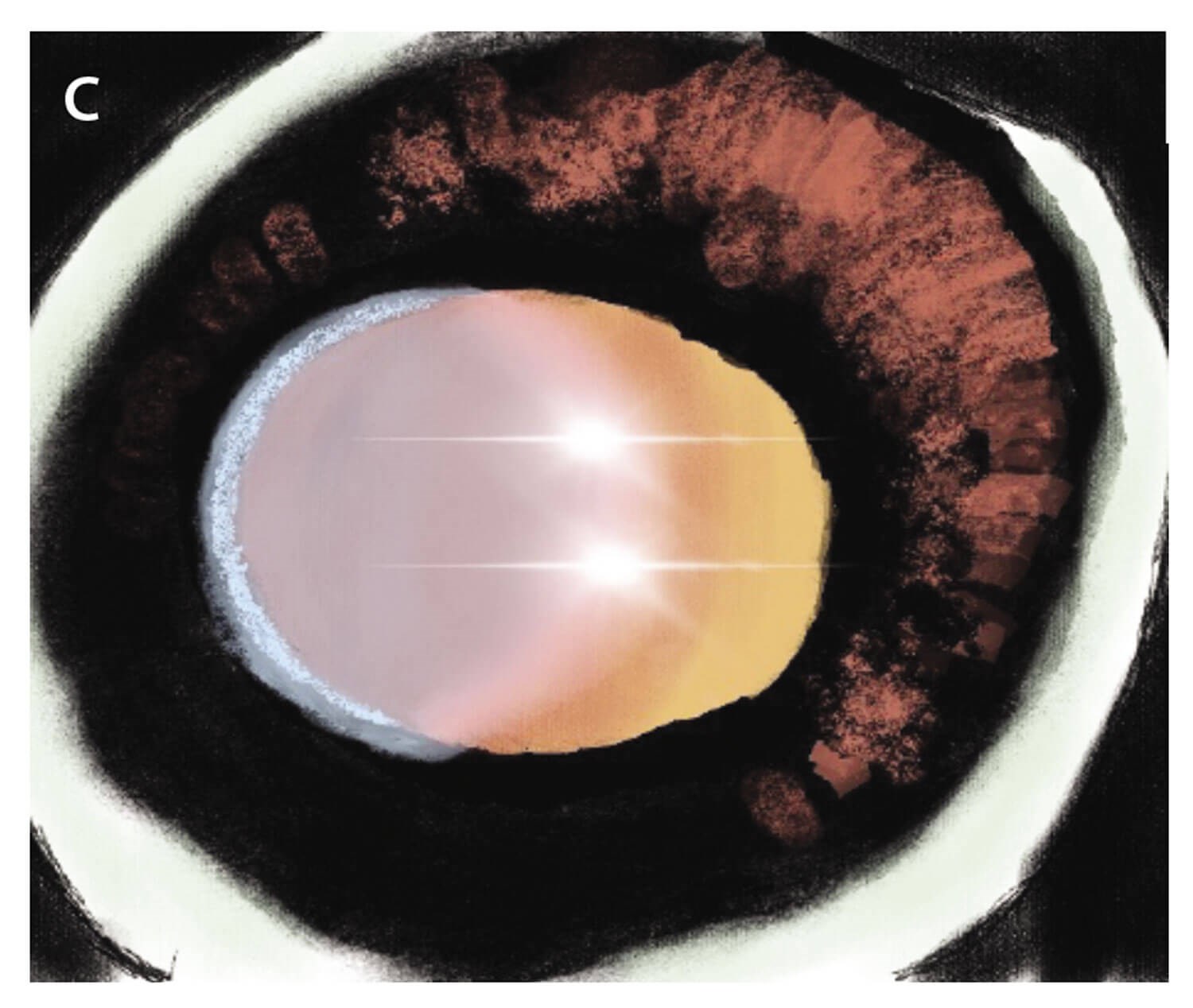

Figure 4: Ultrasound biomicroscopy showing posterior bowing of the iris towards the zonules [5].

Posterior bowing of the iris can be assessed using ultrasound biomicroscopy (see Figure 4). This may also be seen on anterior segment optical coherence tomography where one can see posterior bowing of the iris in the mid peripheral region.

Summary of clinical features

Pigment deposition in anterior chamber

- Corneal endothelium – Krukenberg spindles

- Pigment throughout the trabecular meshwork

- Mid-peripheral iris trans-illumination defect

- Others, e.g. Scheie’s line, other structures in anterior segment, e.g. bleb

Posterior Iris bowing – Ultrasound biomicroscopy or anterior segment OCT.

How should patients with PDS and PG be assessed in clinic?

As well as looking for the aforementioned clinical signs, standard glaucoma investigations should be carried out, including a visual field test, intraocular pressures (IOP) and disc assessment. Furthermore, it may be useful to assess retinal nerve fibre layer thickness on spectral domain optical coherence tomography scans (SD-OCT) as thinning of the ganglion cell layer complex will be associated with PG as opposed to PDS. Aside from these, it is not usually necessary to carry out other further investigations, unless other causes for pigment release are suspected.

What risk factors are associated with PDS?

Pigment dispersion syndrome is an autosomal dominant condition (AD) with particular association to chromosome 7q36. Thus family history is an important risk factor to consider in patients suspected of having PDS or PG [12]. It is important to note that PDS shows incomplete penetrance, thus not all individuals with the genotype will be symptomatic [5]. PDS is also strongly associated with myopia and occurs mostly in young Caucasian men [5,9].

Summary of risk factors

• Family history – Autosomal dominance with incomplete penetrance

• Myopia

• Male sex

• Caucasian

What are the main differentials?

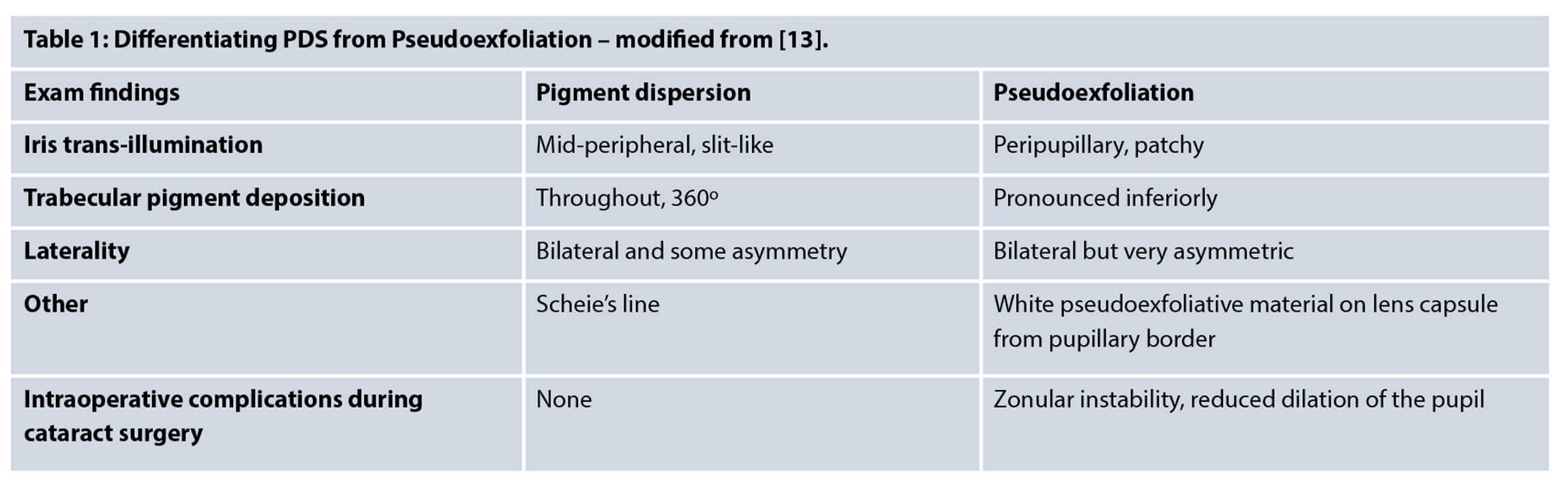

Angle pigmentation is not limited to PDS, and can occur in multiple ocular conditions. These include pseudoexfoliation syndrome (PEX), trauma and iritis, of which PEX may prove to be the most challenging to distinguish from PDS.

The trabecular meshwork pigmentation seen in PEX is patchy compared to that seen in PDS [5]. Furthermore, PDS is usually bilateral, whereas PEX is unilateral in 50% of cases and is particularly seen in the elderly. Iris defects in PEX may be near the pupillary border, however, those seen in PDS are in the mid-peripheral region. Moreover, PEX has the characteristic pseudoexfoliative white material deposit on the lens from the radial iris-lens contact.

In addition, as PDS may present with pigment in the anterior chamber, this may make it difficult to differentiate it from uveitis. Specifically herpetic uveitis, which may show iris trans-illumination defects, raised intraocular pressures and pigmentation of the trabecular meshwork.

Other differentials include syndromes with melanocytic lesions, namely oculodermal melanocytosis and phakomatosis pigmentovascularis [5].

Finally, it is important to consider masquerade syndromes, intraocular tumours such as uveal melanomas and choroidal metastases, as ocular tumours are known to cause pigment release and thus secondary glaucoma.

Summary of differentials

- PEX

- Inflammation – iritis, uveitis, uveitis masquerade syndromes (UMS), herpetic uveitis

- Trauma or intraocular surgery

- Neoplasms – uveal melanoma, choroidal metastases

- Congenital – oculodermal melanocytosis, phakomatosis pigmentovascularis.

What are the treatment options for PG and PDS?

As only 33-50% of patients with PDS develop glaucoma, IOP lowering treatments may not be necessary. Thus, the management of PDS is often observation. If there are no signs of glaucomatous optic neuropathy or ocular hypertension, patients with PDS may undergo six to 12 month reviews.

The mainstay treatment for PG is the same as for primary open angle glaucoma (POAG). These include IOP lowering eye drops, laser therapy (laser PI, argon (ALT), selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT)), and surgery if required.

Laser therapy may be used when medical therapy doesn’t work. However, ALT may cause scarring of the TM thus a possible further rise in IOP may occur following treatment with ALT [14]. Although, SLT has been shown to demonstrate a drop in IOP of 20% in 85% of patients with PG at one year, similar to ALT, a subsequent rise in IOP has still also been noted following SLT treatment.

YAG-laser peripheral iridotomy can be effective in reducing the iris concavity by enabling the equilibration of pressure differences between the anterior and posterior chambers. Consequently, this reduces posterior iris bowing. However, the effectiveness of reducing the progression to glaucoma is debatable as although iris flattening has been seen, some authors have not noted a significant reduction in IOP [15,16].

If both medical and laser therapy don’t work, the surgical management of PG is standard filtration surgery with trabeculectomy, similar to POAG.

Conclusion

In conclusion, PDS is a bilateral ocular disorder which, if not monitored closely, can progress to pigmentary glaucoma and thus cause glaucomatous field defects. The typical clinical features of PDS have been touched upon in this article and should help readers differentiate these from other causes of pigmentary changes in the eye.

References

1. Niyadurupola N, Broadway DC. Pigment dispersion syndrome and pigmentary glaucoma – a major review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2008;36(9):868-82.

2. Lahola-Chomiak AA, Walter MA. Molecular Genetics of Pigment Dispersion Syndrome and Pigmentary Glaucoma: New Insights into Mechanisms. J Ophthalmol 2018;2018:5926906.

3. Kumar S, Acharya S, Beuerman R. Deposition of particles on ocular tissues and formation of Krukenberg spindle, hyphema, and hypopyon. J Biomech Eng 2007;129(2):174-86.

4. Fautsch MP, Johnson DH. Aqueous humor outflow: what do we know? Where will it lead us? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006;47(10):4181-7.

5. Scuderi G, Contestabile MT, Scuderi L, et al. Pigment dispersion syndrome and pigmentary glaucoma: a review and update. Int Ophthalmol 2019;39(7):1651-62.

6. Roy FH, Fraunfelder F, Fraunfelder F. Roy and Fraunfelder’s Current Ocular Therapy. WB Saunders: Philadelphia; 2007.

7. Lichter PR, Shaffer RN. Diagnostic and prognostic signs in pigmentary glaucoma. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 1970;74(5):984-98.

8. Gupta N, Weinreb RN. New definitions of glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 1997;8(2):38-41.

9. Santos-Bueso E, García-Sáenz S, Morales-Fernández L, et al. Scheie’s line as a first sign of pigment dispersion syndrome. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol 2019;94(3):138-40.

10. Lyons L, Amram A. Iris Transillumination Defects in Pigment Dispersion Syndrome. N Engl J Med 2019;381(20):1950.

11. Sayed MS, Ko MJ, Ko AC, Lee WW. Ocular damage secondary to lights and lasers: How to avoid and treat if necessary. World J Ophthalmol 2014;4(1):1-6.

12. Tandon A, Zhang Z, Fingert JH, et al. The Heritability of Pigment Dispersion Syndrome and Pigmentary Glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2019;202:55-61.

13. Aref AA, Callahan CE, Scott IU. Dx and Tx of Pigment Dispersion Syndrome and Pigmentary Glaucoma. EyeNet Magazine January 2009.

14. Ritch R, Liebmann J, Robin A, et al. Argon laser trabeculoplasty in pigmentary glaucoma. Ophthalmology 1993;100(6):909-13.

15. Michelessi M, Lindsley K. Peripheral iridotomy for pigmentary glaucoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016:CD005655.

16. Costa VP, Gandham S, Spaeth G, et al. The effect of nd: yag laser iridotomy on pigmentary glaucoma patients: a prospective study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1994;35: Abstract number 2760.

TAKE HOME MESSAGE

-

Patients with pigment dispersion syndrome (PDS) are at risk of pigmentary glaucoma (PG) (35-50% of PDS patients have PG).

-

Pigmentary glaucoma is the leading cause of non-traumatic blindness in the young population – those between 20-40 years of age.

-

Pigment is released due to the posterior bowing of the iris, causing it to rub against the lens zonules.

-

A triad of clinical features can be seen in PG, including 360-degree pigment deposition in the trabecular meshwork, Krukenberg spindles on the endothelium and mid-peripheral iris trans-illumination defects.

-

Management is similar to treatment for primary open angle glaucoma – IOP lowering drops, laser therapy (laser PI, argon (ALT), selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT)), and surgery if required.

The images used in the article were drawn by the author using Apple’s Procreate® software.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME