Shivam Goyal and Kyaw Htun Aye describe the challenges of dealing with a rare case of congenitial lacrimal fistula.

We present a case of a 19-month-old baby with a congenital abnormality. Congenital lacrimal fistulae are a spot diagnosis due to its pathognomonic appearance. We hope to highlight the importance of early recognition and discussion with parents, GPs and other health care professionals involved with the care. No treatment is usually required when it is asymptomatic. Intervention becomes necessary only when significant epiphora or discharge is present.

Case report

A two-month-old female baby was referred by her GP to the eye clinic due to an abnormality noted at her routine six-week baby check. Her mother noticed a hole near her left inner eye adjacent to the bridge of the nose. The GP was concerned as this was an unfamiliar presentation to them. The baby was 19-months-old when seen in the eye clinic due to delays because of the COVID-19 lockdown.

Figure 1: Appearance on initial presentation, no obvious dysmorphic features seen.

The baby was born full term, via normal delivery, and there was no family history of ocular disease. The parents had no concern regarding the vision and there were no symptoms of watering, discharge or swelling around the eyes. She was fit and well with normal milestones. No dysmorphic features were noted (Figure 1).

Figure 2 & 3: Small pit / hole located inferonasal to the medial canthal angle of the left eye.

On examination, a small pit / hole was noted, located inferonasal to the medial canthal angle of the left eye (Figures 2 and 3). Crying did not elicit any watering from the site. The rest of the ocular examination was within normal limits. A diagnosis of congenital lacrimal fistula was made. The diagnosis was explained to the parents. As it was asymptomatic, it was managed conservatively, and a follow-up was arranged.

Background

Congenital lacrimal fistula is a rare developmental anomaly typically located in the inferomedial aspect of the inner canthus. They are accessory ducts that connect the lacrimal drainage system to the skin. They are thought to arise from an abnormal involution of the lacrimal anlage duct, a solid cord of epithelium incorporated between the lateral nasal and maxillary processes of the developing embryo. Examination of lacrimal sac fistula reveals that it is generally lined with stratified squamous epithelium, similar to that of normal canaliculus [1].

They have been estimated to occur in around 1 in 2000 live births. It can be occasionally inherited as autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive pattern, or rarely can be syndromal [2,3]. Syndromes associated with it are Down’s syndrome, VACTERL (vertebral anomalies, anal atresia, cardiac malformations, tracheoesophageal fistula, renal anomalies, and limb anomalies), CHARGE (coloboma, heart defects, atresia choanae, retarded growth and development, genital hypoplasia, ear anomalies), ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-cleft (EEC) syndrome, uterus didelphys and renal agenesis. There is no sex or racial predilection, and cases are often unilateral. The classification of congenital lacrimal fistula is based on the origin of its tract, which may originate from common canaliculus, the lacrimal sac or nasolacrimal duct [4]. Rarely, the fistulae tract can end as a blind-ended tube, terminating in subcutaneous tissue near the lacrimal sac [1].

Symptoms, examination, and diagnosis

Congenital lacrimal fistulae are frequently asymptomatic. Sometimes they can present with watering or mucoid discharge from the fistula or the eye, or both. Usually, symptoms are present since birth, but can present later. Blepharitis and increased tearing in windy weather has also been reported [5].

Tearing from fistula may be noticed when a child cries. If associated with nasolacrimal duct obstruction, fullness may be present in the lacrimal sac area resulting in discharge from the eye upon pressing that area. Rarely, patients can have persistent dacrocystitis.

Though the typical opening of the fistula is inferonasal to the medial canthal angle, as in our case, it may occur anywhere along skin surface of the eyelids around the medial canthal angle and even on the conjunctival surface [6]. Irrigation of the lacrimal sac with fluorescein can be used to identify any skin ostium and check the patency of the nasolacrimal duct. A fluorescein disappearance test can be used in infants to ascertain the patency of the lacrimal system.

Management

Asymptomatic congenital lacrimal fistula, especially when not associated with nasolacrimal duct obstruction, do not require treatment. Symptomatic fistulae, however, require treatment.

The recommended surgical management of lacrimal fistula remains controversial. In 1929, Levine reported cauterising a lacrimal fistula in a seven-year-old boy with successful closure, but the patient developed secondary epiphora from presumed damage to the lacrimal drainage system.

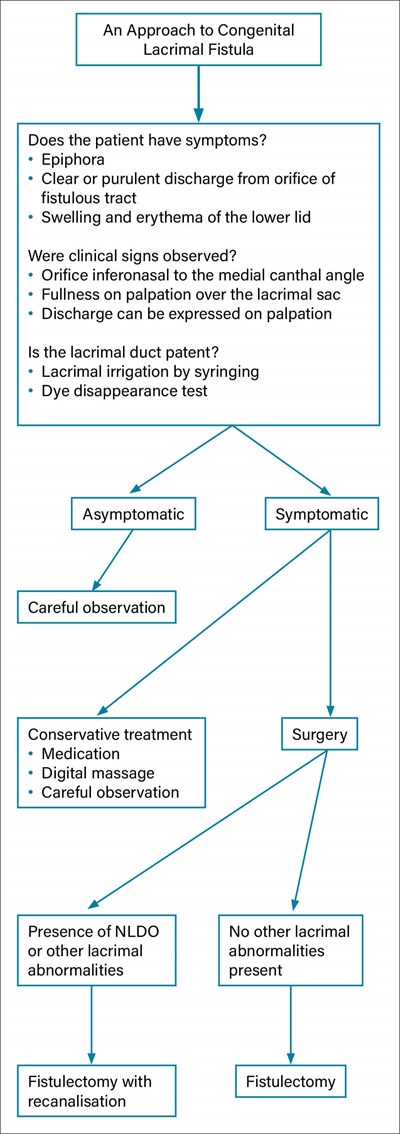

Figure 4: Approach strategies in managing congenital lacrimal fistulas.

Treatment modalities reported for symptomatic fistulae are nasolacrimal duct probing, cauterisation of the external ostium and fistulectomy with or without dacryocystorhinostomy. Procedures such as simple probing and cautery can be dangerous if the fistula originates from the common canaliculus. It is of paramount importance to check the patency of the lacrimal drainage system prior to any surgical intervention to minimise the risk of postoperative epiphora or dacrocystitis. It has been recommended that lacrimal fistulae can be treated by simple excision of the fistula tract without additional lacrimal outflow surgery in cases with otherwise normal outflow tracts. However, fistulectomy with lacrimal intubation is recommended for cases with canalicular stenosis or unresolved congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction and dacryocystorhinostomy for cases with refractory nasolacrimal duct obstruction or dacrocystitis [7]. Figure 4 demonstrates a simple clinical pathway for investigations and managements for this condition reported in literature [8].

References:

1. Sevel D. Development and congenital abnormalities of the nasolacrimal apparatus. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1981;18(5):13-9.

2. François J, Bacskulin J. External congenital fistulae of the lacrimal sac. Ophthalmologica 1969;159(4):249-61.

3. Maden A, Yilmaz S, Ture M. Hereditary lacrimal fistula. Orbit 2008;27(1):69-72.

4. Toda C, Imai K, Tsujiguchi K, et al. Three different types of congenital lacrimal sac fistulas. Ann of Plast Surg 2000;45(6):651-3.

5. Masi A. Congenital fistula of the lacrimal sac. Arch Ophthalmol 1969;81(5):701-4.

6. Ishikawa S, Shoji T, Nishiyama Y, Shinoda K. A case with acquired lacrimal fistula due to Sjögren’s syndrome. Am J Ophthalmology Case Rep 2019;15:100526.

7. Al-Salem K, Gibson A, Dolman P. Management of congenital lacrimal (anlage) fistula. Br J Ophthalmol 2014;98(10):1435-6.

8. Chaung J, Sundar G, Ali M. Congenital lacrimal fistula: a major review. Orbit 2016;35(4):212-20.

TAKE HOME MESSAGE

-

Recognition of this rare entity to prevent undue concern amongst parents.

-

Rarely can have syndromal associations which need to be excluded.

-

Requires thorough examination of globe, adnexa, and lacrimal system.

-

Asymptomatic cases do not require any intervention

-

Essential to determine the patency of lacrimal drainage system before any intervention.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank the patient and family who generously consented for their medical history and clinical experience to be written up and repurposed for Eye News.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME