Clinical scenario:

A 57-year-old gentleman who is scheduled to have Mohs micrographic surgery and reconstruction for a medial canthal basel cell carcinoma (BCC) has been started on aspirin and clopidogrel following a coronary stent three weeks ago.

Does the antiplatelet / anticoagulation need to be stopped, can it be stopped?

The approach to perioperative management of thrombotic agents lies firstly in deciding if the bleeding risk for the particular ophthalmic surgery warrants modification of antithrombotic therapy and if it overrides the risk of the patient having an event while without protection. If so, the question is then how best to do it safely.

What is the patient on antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy for?

Antithrombotic agents are typically used in the field of stroke prevention, in atrial fibrillation (AF), the management of venous thromboembolism (VTE), in patients with mechanical heart valves, in the treatment of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and in the primary / secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Treatment for these conditions is constantly evolving, with novel agents coming into the market. Guidance is regularly updated, hence the ophthalmologist needs to have an up-to-date working knowledge of these agents.

What are the indications for antiplatelet agents?

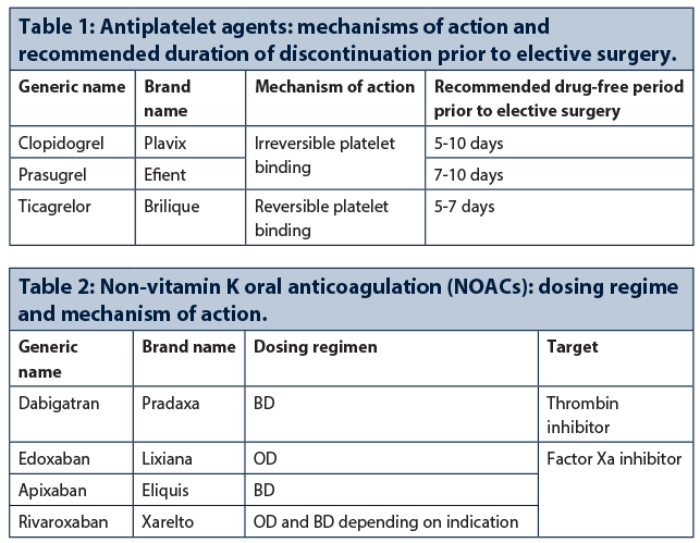

Aspirin is used for primary and secondary prevention of stable coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndromes. Newer antiplatelet agents, such as the P2Y12 inhibitors (Table 1), are approved for use in: ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (n-STEMI), unstable angina (UA) and in combination with aspirin as dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).

DAPT is indicated for secondary prevention in patients with ACS to prevent potentially fatal recurrences and following coronary artery stenting to prevent stent thrombosis. A one-year duration of DAPT in NSTE-ACS patients is recommended; but DAPT duration may be shortened (three to six months) or extended (up to 30 months) in selected patients if required, based on individual patient ischaemic and bleeding risk profiles.

What are the indications for warfarin and the novel anticoagulants?

Warfarin is used for prophylaxis of stroke and systemic embolism in people with rheumatic heart disease and AF, prophylaxis after insertion of prosthetic heart valves, prophylaxis and treatment of VTE and transient ischaemic attacks.

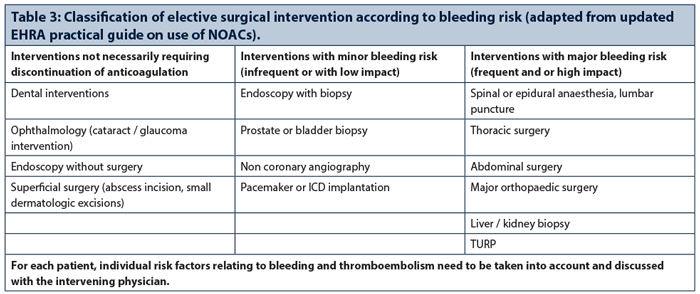

The novel anticoagulants, now termed non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants (NOACs) (Table 2) act directly by inhibiting factor Xa or antithrombin III. Dabigatran, apixaban, rivaroxaban and edoxaban are all licensed for use in prevention of stroke and systemic thromboemblism in non-valvular AF with additional risk factors, as well as the treatment and prevention of recurrent deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism. Broadly speaking they cover the indications of warfarin with the exception of valvular conditions and prosthetic valves.

What is the risk of bleeding for the procedure?

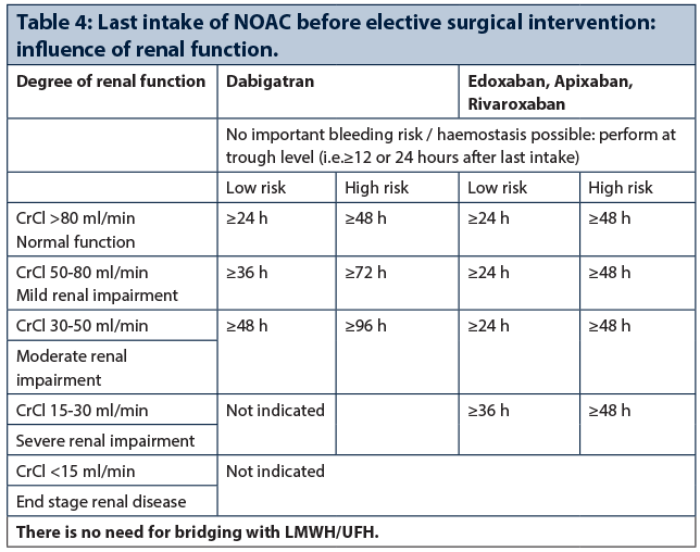

The European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) in their recently updated guide classifies ophthalmic surgery as having minimal bleeding risk not necessarily requiring cessation of anticoagulation (Table 3). Although it is difficult to place the spectrum of various ophthalmic procedures into these categories in comparison to surgery with major bleeding risks (such as cardiothoracic or abdominal surgery), bleeding in some ophthalmic interventions may have a higher impact due to its limited surgical field.

Previous publications have suggested that there is no evidence of increased bleeding risk in peribulbar / retrobulbar anaesthesia, cataract surgery and intravitreal injections. Although results are more conflicting in vitreoretinal surgery, the risk may be reduced with smaller gauge surgery. Procedures perceived as having higher risk include trabeculectomy, orbital surgery and dacryorhinocystostomy due to the possibility of sight-threatening haemorrhage or retro-orbital haematoma. While oculoplastic procedures (where superficial haemostasis is possible) can be viewed as minor dermatological procedures, postseptal surgery carries a higher risk.

What to do with antiplatelet agents?

In patients taking antiplatelet for primary prevention, aspirin can be stopped seven to ten days prior to surgery if a decision to stop antiplatelet agents has been made.

Interruption of DAPT increases the risk of stent thrombosis and recurrent events, particularly when the recommended course of therapy has not yet been completed. Treatment withdrawal should therefore be undertaken with the agreement of the patient’s cardiologist.

In the case of a non-cardiac surgical procedure that cannot be postponed, a minimum of one month for DAPT for bare-metal stents (BMS) and three months for new-generation drug eluting stents (DES) might be acceptable. In this setting, surgery should be performed in hospitals with 24-hour catheterisation laboratory availability, so that in the case of perioperative myocardial infarction, treatment may be provided immediately.

Whenever possible, aspirin should be continued; early discontinuation of both antiplatelet drugs will further increase the risk of stent thrombosis. If a decision has been made to stop the second antiplatelet agent, clopidogrel and ticagrelor should be discontinued five days and prasugrel seven days before surgery. If the patient is at high risk of thrombosis a multidisciplinary decision is required to determine the best strategy.

If interruption of DAPT is mandatory because of urgent high-risk surgery (e.g. neurosurgery) or in the case of a major bleed that cannot be controlled by local treatment, there is no alternative therapy as a substitute for DAPT to prevent stent thrombosis. Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) has been advocated, but the proof of efficacy for this indication is lacking.

In patients on DAPT following an episode of NSTE-ACS that was treated conservatively (i.e. not stented), it may be possible to temporarily discontinue the second antiplatelet agent after discussion with the patient’s cardiologist.

In surgical procedures with low to moderate bleeding risk, surgeons should be encouraged to operate on patients on DAPT. In all cases, the merits of deferring the elective procedure versus performing the procedure with concomitant DAPT should be considered.

What to do with warfarin?

In procedures with minimal bleeding risk, it may be feasible and safe to perform surgery while the international normalised ratio (INR) is at the low end of the therapeutic range.

In patients undergoing higher risk elective surgery that requires their INR to be near normal at the time of surgery, it is recommended that patients stop taking their warfarin five days preoperatively. For patients in whom the risk of thromboembolism is judged high when their INR is dropped below their target therapeutic range (e.g. those with mitral metallic heart valves or AF patients with a history of thromboembolic stroke), then bridging with LMWH or unfractionated heparin (UFH) may be necessary. Warfarin should be restarted 12-24 hours postoperatively, typically the evening after surgery, once haemostasis has successfully been achieved.

What to do with non-Vitamin K antagonist anticoagulation?

For interventions with no clinically significant bleeding risk, the procedure can be performed at trough concentration (12-24 hours after the last intake depending on once daily or twice daily dosing by omitting one dose before the procedure and recommencing six hours after).

It is recommended to discontinue NOACs 24 and 48 hours before procedures with minor and high bleeding risk, respectively. These intervals need to be longer in patients with impaired renal function, especially for dabigatran (Table 4).

NOACs can be resumed six to eight hours after procedures with immediate and complete haemostasis.

Is there a need for bridging therapy?

Warfarin

In patients where warfarin cessation is required, bridging therapy should be guided by risk stratification according to the likelihood of thromboembolic events, since concomitant use of heparin and warfarin carries an inherent risk of bleeding.

NOACs

Bridging is unnecessary in patients treated with NOACs since the predictable waning of the anticoagulation effect allows properly timed short-term cessation and re-initiation of therapy. However, if resuming anticoagulation in the first 48-72 hours carries a bleeding risk that could outweigh the risk of thromboembolism, a reduced thromboprophylactic or intermediate dose of LMWH can be administered.

DAPT

Intravenous bridging therapy with small molecule GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors (i.e. tirofiban or eptifibatide) has been used for premature interruption of DAPT in a selected patients undergoing urgent high risk non-cardiac surgery. Similarly, cangrelor (a P2Y12 inhibitor with short half life) has been trialled prior to cardiac surgery.

Are there antidotes for NOACs?

Idarucizumab (Praxbind), a specific antidote to dabigatran, has recently been approved. Andexanet, an antidote for Factor Xa inhibitors, awaits approval. Although these antidotes are only to be used in the setting of life-threatening bleeds, various existing supportive measures for bleeding can also be applied.

In a nutshell…

The risks of bleeding must be carefully balanced against that of perioperative thromboembolism (particularly valve or stent thrombosis) before stopping antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy; the decision should be made in conjunction with the physician responsible for the antithrombotic therapy, especially in high risk cases. Ultimately, the onus for ensuring that there are measures in place for the safe interruption and reinitiation of therapy falls upon the operating surgeon.

Further reading

- Kiire C, Mukherjee R, Ruparelia N, et al. Managing antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs in patients undergoing elective ophthalmic surgery. Br J Ophthalmol 2014;98:1320-4.

- Heidbuchel H, Verhamme P, Alings M, et al. Updated European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Europace 2015;17: 1467-1507.

- Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet J et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European Heart Journal 2016;37(3):267-315.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME