A nine-year-old girl presented to me in eye casualty with a three-week history of blurred vision in her left eye. Otherwise she was apparently well, with no past ophthalmic, medical, drug or relevant family history.

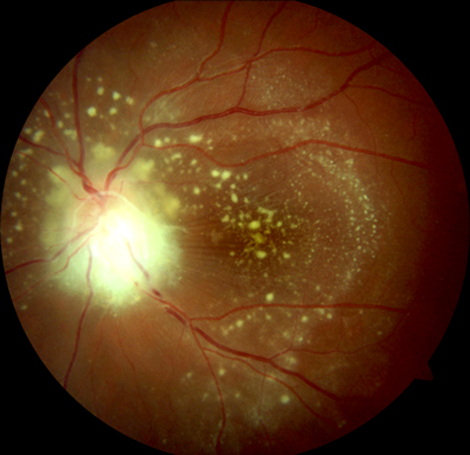

Visual acuity was 6/4 right and 3/60 left. There was a left relative afferent pupillary defect. The anterior segment of both eyes, intraocular pressure and right fundus was normal. Fundoscopy of the left eye showed a swollen disc, retinal folds and a striking array of circinate exudates in a peri-papillary and macular location (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Left eye neuro-retinitis (optic disc swelling, peri-papillary and macular exudates,

retinal folds), potentially from a feline friend. The right eye was normal.

“CAT SCRATCH!” I thought. Could this be neuro-retinitis secondary to Bartonella henselae? Further questioning confirmed that the girl had four cats (two were kittens) and often had received otherwise, seemingly harmless, cat scratches. Furthermore, prior to her loss of vision, for the preceding month had suffered a headache, coryzal symptoms and intermittent fever.

Refusing to jump to the diagnosis and assume correct pattern recognition at this stage, a thorough review ensued. There were no other features in the history that could be elicited (such as infectious contacts or foreign travel). Immunisation history was complete. Importantly, blood pressure was normal (given that unilateral disc swelling / exudates can occur with malignant hypertension).

There was no rash, no joint swelling or lymphadenopathy. Extensive blood testing (including full blood count, renal and hepatic profile, inflammatory markers, serology for lyme, toxoplasmosis, HSV, zoster) was normal except for a positive result for Bartonella henselae (IgG above 512). Electro-diagnostic testing was normal in the right eye, but in the left eye the visual evoked potential was abolished and the electro-retinogram was absent, confirming both impaired nerve and retinal function.

Given the rarity and severity of the condition, prompt advice and review from the regional ocular inflammatory disease service was sought and the diagnosis of Bartonella neuro-retinitis was confirmed. This did indeed appear to be cat scratch disease. Treatment was commenced with oral doxycycline and rifampicin for the Bartonella infection and within two weeks vision had improved in the left eye to 6/9.5. Pulsed intravenous methylprednisolone was considered, but given the systemic adverse effects of this medication combined with the improvement of the condition with the anti-microbials this was not prescribed.

The striking appearance of neuro-retinitis was first described in the 19th century by the German ophthalmologist Theodor Karl Gustav von Leber. Subsequently, a variety of conditions have been recognised to cause such an appearance, including cat scratch disease [1,2]. Cat scratch disease can cause a variety of symptoms and signs, typically including fever, headache, lymphadenopathy and joint swelling which are usually benign and settle within a few weeks. Rarely, cardiac and neurological systems are affected by endocarditis or encephalitis. Ophthalmic involvement occurs in 5-10% of patients with cat scratch disease [3]. Usually such ocular involvement includes Parinaud’s oculo-glandular syndrome (conjunctivitis and pre-auricular lymphadenopathy) and less commonly neuro-retinitis. Bartonella neuro-retinitis in the majority of patients will improve spontaneously, but in 17-21% of patients retinal vascular occlusion can occur [4,5].

Fortunately, like the majority of patients with Bartonella neuro-retinitis, our patient recovered well. Although the diagnosis jumped to mind, given the striking appearance of the fundus, it is important to investigate patients thoroughly with this fundoscopy finding since a variety of pathologies can present like this.

The differential diagnosis for neuro-retinitis includes idiopathic, infective and non-infective pathologies. Infective pathologies include cat-scratch disease, lyme disease, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, tuberculosis, herpes simplex and varicella. Non-infective pathologies include malignant hypertension and vasculitic diseases such as polyarteritis nodosa. Our patient had no other symptoms or signs suggestive of these other diagnoses and investigations relating to them were negative. The history of cat and kitten scratches, fever, headache, neuro-retinitis and positive Bartonella serology are sufficient to make the clinical diagnosis of cat scratch disease.

Acknowledgements:

I would like to thank the patient and their family for allowing the publication of their story. I would also like to thank Mr Steve Slater (Medical Photographer, Plymouth Royal Eye Infirmary) and Mr Tim Freegard (Consultant Ophthalmologist, Plymouth Royal Eye Infirmary) for helping with this case report.

References

1. Dreyer RF, Hopen G, Gass JD, Smith JL. Leber’s idiopathic stellate neuroretinitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1984;102:1140-5.

2. Dolan MJ, Wong MT, Regnery RL, et al. Syndrome of Rochalimaea henselae adenitis suggesting cat scratch disease. Ann Intern Med 1993;118:331-6.

3. Carithers HA. Cat scratch disease: an overview based on a study of 1,200 patients. Am J Dis Child 1965;1139:1124-33.

4. Ormerod LD, Skolnick KA, Menosky MM, et al. Retinal and choroidal manifestations of cat scratch disease. Ophthalmology 1998;105:1024-31.

5. Solley WA, Martin DF, Newman NJ, et al. Cat scratch disease: posterior segment manifestations. Ophthalmology 1999;106:1546-53.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME