History

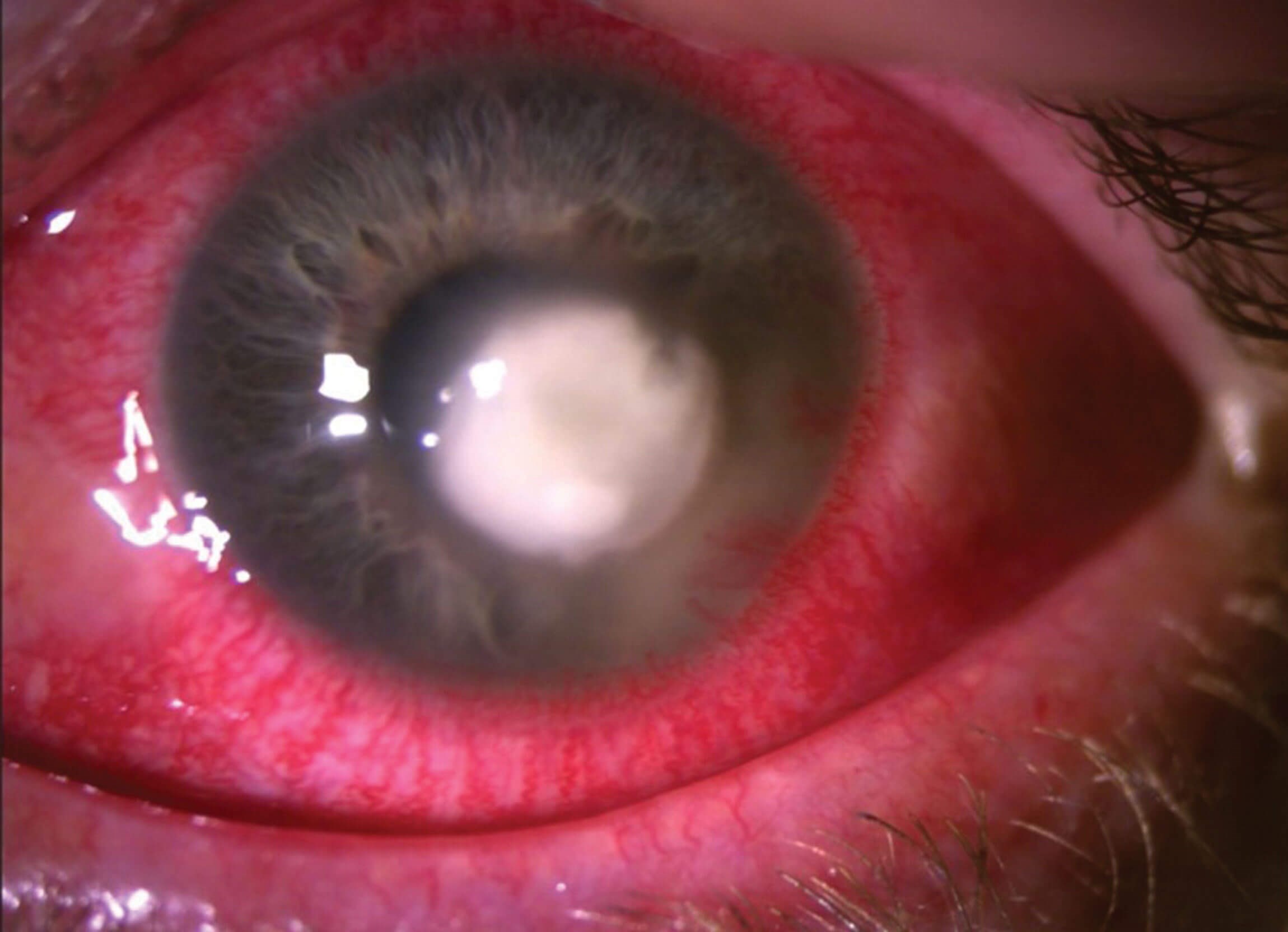

A 35-year-old female presented to the emergency eye clinic with an acutely red, painful, photophobic left eye. She was a contact lens-wearer but denied swimming, showering, or sleeping in her lenses. She resided on a farm and worked as a horse groom. On examination vision in the left eye was 6/6 aided. The eye was intensely hyperaemia and there was a dense corneal infiltrate, overlying epithelial defect (Figure 1). Corneal samples were taken for culture and sensitivity and polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Hourly levofloxacin and teicoplanin eye drops were commenced.

Staphylococcus vitulinus was cultured and PCR was positive for acanthamoeba DNA. Pan-fungal (18S) DNA was negative. Polyhexamethylene biguanide 0.06% drops were added to the treatment regimen. However, the ulcer and corneal neovascularisation increased. A month after initial presentation the cornea perforated and a therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty was performed. Further samples were taken at that point for microbiology and the corneal button was sent for ophthalmic pathology assessment.

Figure 1: Anterior segment.

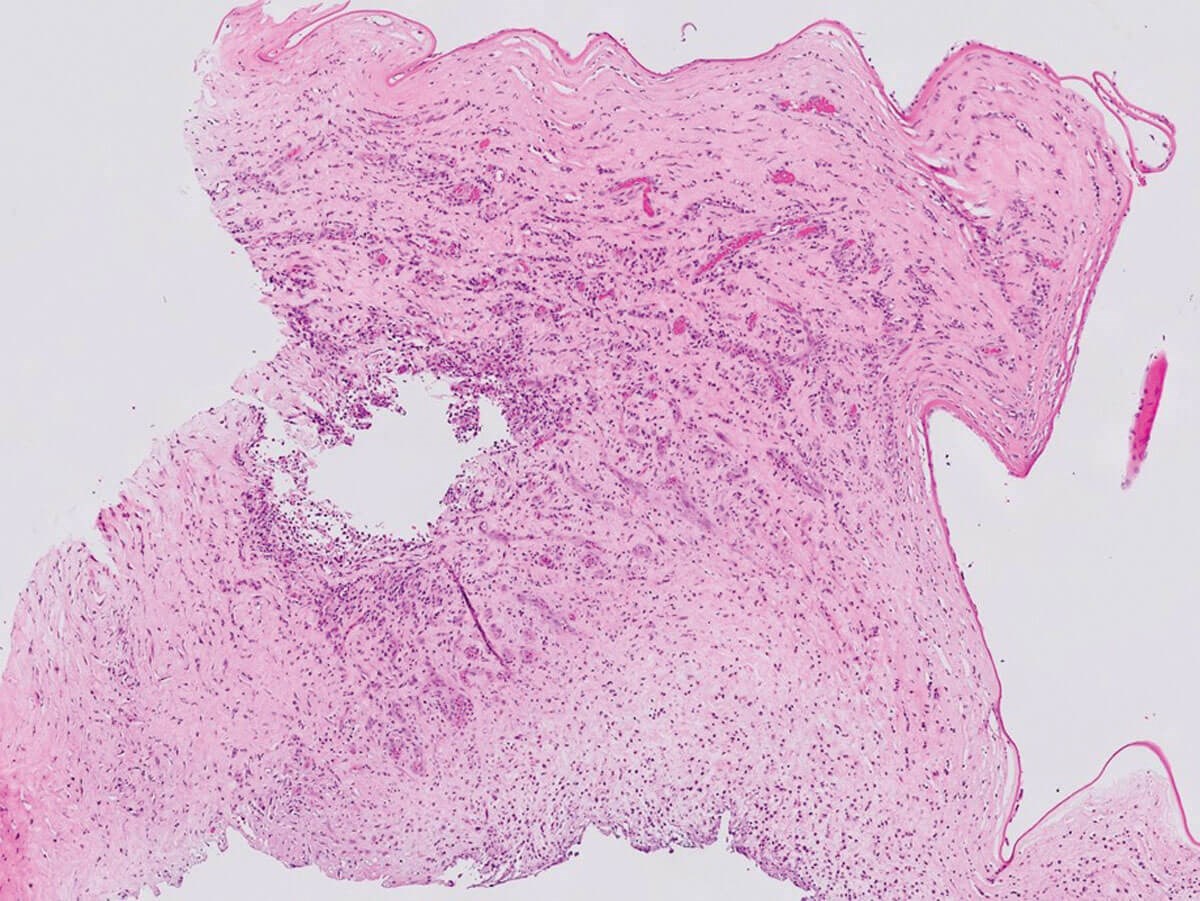

Figure 2a: H&E x20.

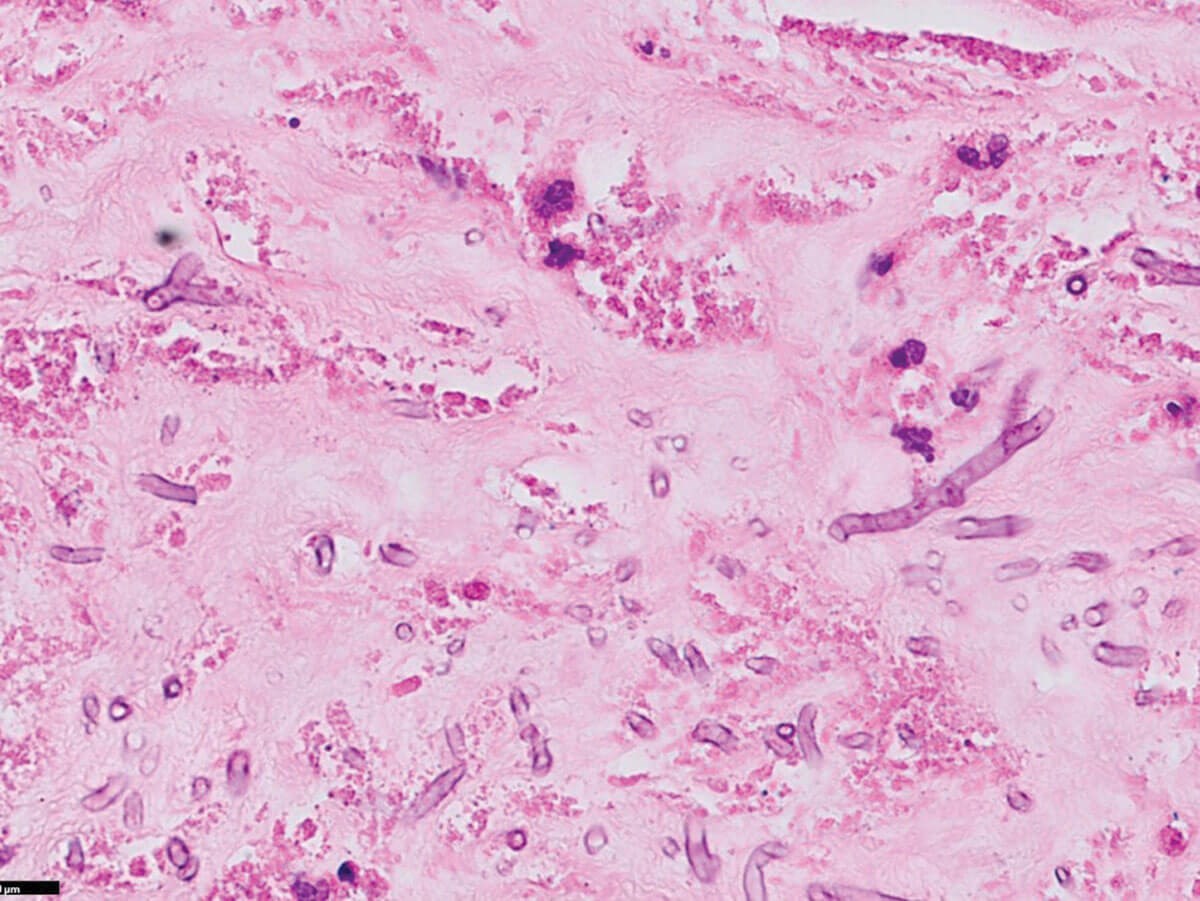

Figure 2b: H&E x400.

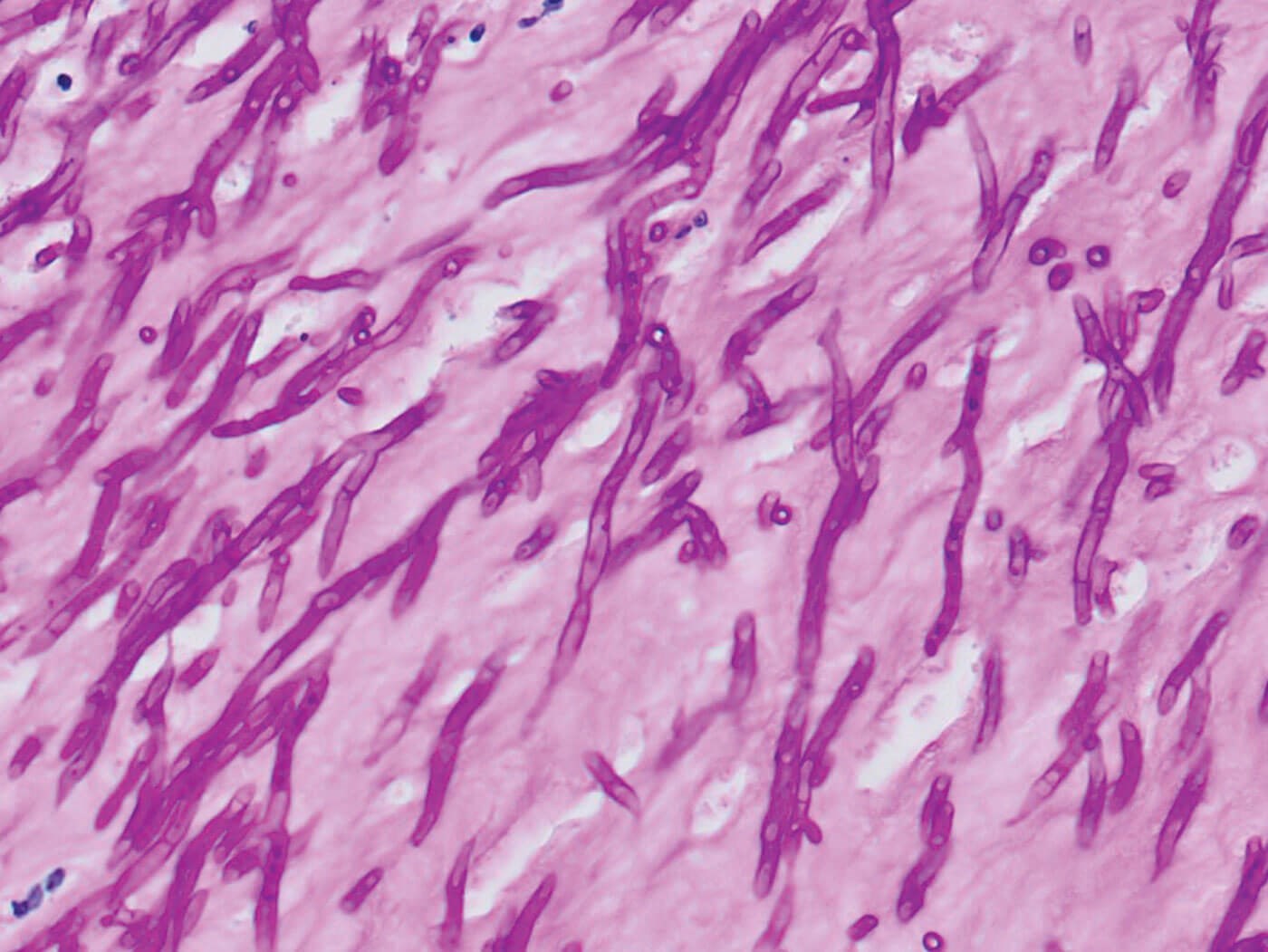

Figure 3: Diastase-PAS x400.

Questions

- What do Figures 2a and 2b show?

- What special stain(s) can be used to highlight the diagnostic features?

- What is the diagnosis?

- What are the risk factors associated with the diagnosis?

Answers

1. Severe acute keratitis with severe ulceration, complete sloughing of the epithelium and loss of Bowman’s layer. Some viable cornea remains. Figure 2b shows thin fungal septate hyphae with 45° branching (Y-shaped), favouring Aspergillus species.

2. Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), diastase-PAS (DPAS, Figure 3), and Grocott methenamine silver stains will all highlight the organisms.

3. Microbial keratitis is a common but sight-threatening ophthalmic emergency. It is treatable but common pitfalls include diagnostic delay, inappropriate sample collection, inadequate therapy, and delayed follow-up. The condition can be polymicrobial and early corneal samples should be sent for microbiological assessment. If the patient is a contact lens-wearer, then the lens, solutions and / or case should also be sent. In atypical cases and / or where there is a suspicion of Acanthamoeba or fungal keratitis, samples should be sent for PCR for these organisms and in vivo confocal microscopy can detect cysts and fungal hyphae. Corneal biopsies should also be sent for histopathological assessment, especially if there is no confocal microscopy available.

Acanthamoeba cysts can usually be seen on H&E and on special stains (Giemsa). Fungal hyphae and spores can also be easily highlighted by special stains (DPAS, in this case). Fungal elements are often found deep in the ulcer bed or in the adjacent viable stroma.

Fusarium and Aspergillus species (filamentous fungi more common found in warmer climates) and Candida (a yeast more common in cooler climates) are the most common pathogens. Although much more common in tropical climates, the incidence is increasing in the UK and the diagnosis should be considered when the ulcer does not respond to or progresses after initial antibiotic treatment. Microscopic features are common to fungal and bacterial infections: epithelial destruction / ulceration, necrosis, neutrophilic infiltration, stromal oedema and neovascularisation, and discontinuities of the Descemet membrane. If fungal organisms can be visualised typing according to their morphology is usually possible.

Fungal infections are treated with broad-spectrum topical anti-fungals, first line treatment being natamycin for filamentous fungi. Systemic therapy and surgical management may be necessary depending on severity and complications.

4. Risk factors for fungal keratitis include trauma (including iatrogenic), foreign bodies / contamination with organic matter, contact lens wear (especially extended wear; poor contact lens care / hygiene), ocular surface disease, and immunosuppression (long-term topical steroid use, alcoholism, diabetes mellitus). Fungal keratitis is the most common cause of trauma-related infectious keratitis, especially in agricultural communities and risk is often compounded by lack of eye protection. Postoperatively and on receipt of the histopathology results, the patient was commenced on natamycin. The graft remains clear and there have been no signs of re-infection.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME