Case report

A 55-year-old Caucasian female presented to her general practitioner with a three-month history of headaches and worsening blurred vision in the left eye. On further close questioning, she reported no eye pain, intermittent floaters and flashes of light in her left eye, and what she described as a ‘foreign body sensation’ in the left eye.

There was no ocular history and the only relevant past medical history was essential hypertension. Her most recent eye test was six months prior and visual acuity at the time was 6/6 in both eyes. She was advised to visit eye casualty.

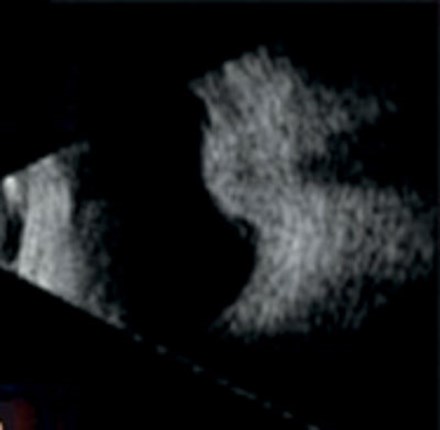

Figure 1: Typical dome-shaped choroidal lesion on B scan ultrasonography [7].

In eye casualty, ocular examination revealed normal visual acuity in the right eye (6/6), but markedly reduced acuity in the left eye (6/24). Pupils were equally round and reactive to light without a relative afferent pupillary defect. Applanation tonometry was 15mmHg in both eyes. On testing eye movements, there was no evidence of ophthalmoplegia, although there was marked redness in the superior sclera of the left eye. Slit-lamp examination showed no sentinel vessels and normal iris.

Fundus examination revealed an irregularly shaped, moderately pigmented opacity in the left fundus with disruption of Bruch’s membrane. Following these findings, A and B-scan ultrasonography (US) was performed. B-scan US revealed an irregular peaked choroidal mass 6mm with an exudative retinal detachment inferior to the mass. The lesion demonstrated low to medium reflectivity on A-scan US.

Based on the clinical findings and ultrasound scan results, the patient was diagnosed with a left eye ciliochoroidal melanoma with iridocorneal angle invasion and extraocular extension. The patient underwent appropriate investigations for tumour staging, which were negative for evidence of metastasis. The size of the melanoma meant she was not eligible for local treatment with radiation and subsequently underwent a left eye enucleation. She struggled with the diagnosis and was shocked by the news as she was unaware of how serious the condition could be. Her mood was severely affected and she felt irresponsible for not seeking help sooner. Cytogenetics was performed and the patient was informed that her life expectancy was less than five years due to probable spread to the liver. Unfortunately, she passed away within two years.

Discussion

This case highlights some key learning points. Firstly, from a diagnostic point of view, choroidal melanoma is the most common primary intraocular tumour. Therefore, it is important to be aware of how it presents and its risk factors. Choroidal melanoma typically arises in Caucasians with fair skin [1], with the mean age of diagnosis in mid-50s. Choroidal melanomas are associated with high mortality rates [2] and have a high propensity to metastasise [3].

Many studies report that general practitioners lack confidence in their ability to use the direct ophthalmoscope and to recognise pathology [4]. Therefore, commonly the patient is referred with no idea of possible diagnoses as fundoscopy has either not been performed or the findings not correctly interpreted to the patient. Typical features of a choroidal melanoma on fundus examination include a well-circumscribed, dome-shaped pigmented lesion. Other differentials to be aware of for a pigmented fundus lesion include a choroidal naevus (a benign melanocytic lesion of the choroid) and choroidal detachment.

Management of choroidal melanoma is dependent on the size of the tumour, location and the effect on the patient’s vision, with the goal being to preserve the eye when possible. Features that suggest a poorer prognosis include ciliary body involvement, extrascleral tumour extension, anterior location and older age of the patient at diagnosis. A metastatic workup should be completed for every patient with a suspected diagnosis of choroidal melanoma. This includes full general examination, blood tests (full blood count, liver function tests), and imaging (chest x-ray and US).

Whilst making the diagnosis is clearly important, ophthalmologists must also be prepared to discuss the potential for malignancy and disclose the bad news in a sensitive and appropriate manner. Breaking bad news to any patient can be difficult, but especially so in this case as the disease is so rapidly progressive. Evidence shows that a doctor’s communication skills play a crucial role in how well patients cope with bad news [5]. Other factors such as a patient’s life experience, personality, spiritual beliefs and social supports also play a role in how a patient responds. As a general practitioner this information must be considered when deciding exactly how to break bad news and what services to offer the patient. Furthermore, as with most cases of breaking bad news, it does not need to be a single event, but rather most patients benefit from a gradual building towards the news with numerous warning signals [6].

References

1. Margo CE. The Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study: an overview. Cancer Control 2004;11(5):304-9.

2. Kujala E, Mäkitie T, Kivelä T. Very long-term prognosis of patients with malignant uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003;44(11):4651-9.

3. Diener-West M, Reynolds SM, Agugliaro DJ, et al. Development of metastatic disease after enrollment in the COMS trials for treatment of choroidal melanoma: Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group Report No. 26. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123(12):1639-43.

4. Schulz C, Hodgkins P. Factors associated with confidence in fundoscopy. Clin Teach 2014;11(6):431-5.

5. Joekes K. Breaking bad news. In: Cambridge Handbook of Psychology, Health and Medicine, Second Edition. Cambridge University Press; 2007:423-6

6. Horikawa N, Yamazaki T, Sagawa M, et al. The disclosure of information to cancer patients and its relationship to their mental state in a consultation-liaison psychiatry setting in Japan. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1999;21(5):368-73.

7. Mithal KN, Thakkar H, Tyagi M, et al. Role of echography in diagnostic dilemma in choroidal masses. Indian J Ophthalmol 2014;62(2):167-70.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME