This article outlines a case of atypical ocular toxoplasmosis associated with immunosuppression. There were two potential sources of infection in this patient and we describe how we concluded which was the most likely.

Case report

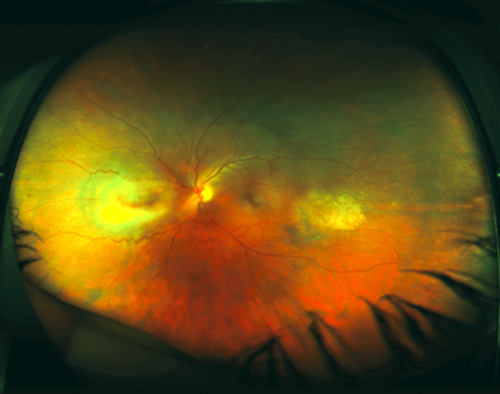

A 33-year-old female was referred to the uveitis service at St Paul’s Eye Unit from a nearby ophthalmology unit. Her presenting complaint was a two week history of unilateral blurred vision and floaters. Her past ocular history included refractive surgery. Her past medical history revealed that she had undergone liver transplantation six months ago for autoimmune hepatitis. She was immunosuppressed with tacrolimus and mycophenolate. In the affected eye, her unaided visual accuity (VA) was 6/5. She had 2+ cells in the anterior chamber and vitritis. Fundoscopy revealed two foci of chorioretinitis with no haemorrhage or pigmentation (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Colour wide-field image of patient’s left fundus.

There are two foci of chorioretinitis with the area nasal to the disc being more active.

She was referred with the provisional diagnosis of viral retinitis. However, we felt that the fundal appearance was more in keeping with toxoplasmosis. We performed an anterior chamber (AC) tap in clinic and admitted the patient. We also ordered serological testing for toxoplasma, syphilis, HIV and quantiferon test. Our treatment strategy comprised of antiviral cover with IV acyclovir, empirical treatment of toxoplasmosis with clindamycin, and on the advice of the infectious diseases team, prophylactic cover with co-trimoxazole.

On the same day, microbiology notified us that the AC tap did not amplify any viral DNA. Toxoplasma serology result became available within a few days and was suggestive of a recent infection (IgM +ve, IgG –ve). The key result was that aqueous polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was positive for toxoplasmosis.

The patient reported improvement and resolution of her symptoms with treatment. On further questioning she revealed that her mother’s cat had moved in two months ago.

The patient’s hepatology team in Birmingham confirmed that our patient’s pre-transplant serum was negative for toxoplasma and that the liver donor was serologically positive for toxoplasma.

Cat or donor liver?

Despite the fact that cats are the definitive host there is no conclusive evidence in the literature to say that cat ownership per se is a risk factor for ocular toxoplasmosis. An epidemiological study in 2009 [1] reports having three or more kittens as a statistically significant risk factor. This is because a litter of kittens are more exposed to risks and are more likely to be infective. It is thought that a litter of kittens may be fed dead animals (such as rodents and birds) and subsequently become infected with T.gondii. Via their faeces, a litter of kittens could shed oocysts which survive for months to years in the soil. Oocysts are responsible for infection of humans directly through ingesting contaminated soil or contaminated food or water. Our patient was cat-sitting an adult cat.

Another way of acquiring toxoplasma infection through cysts is by transplantation of an organ from an infected donor to an uninfected recipient.

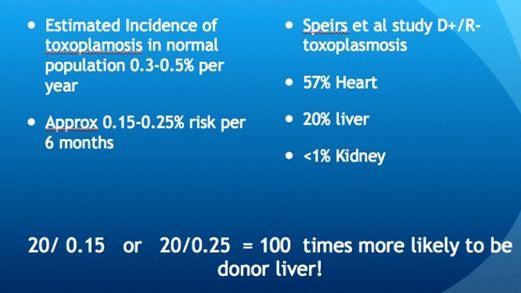

The estimated incidence of toxoplasmosis is 0.3-0.5% per year in the UK from standard agency reports, or 0.15-0.25% over six months. The incidence in donor / recipient mis-matched organs is much higher. Speirs et al. [2] reported that 20% of T.gondii-antibody-negative recipients of livers from T.gondii-antibody-positive donors acquired primary T.gondii infection. This would make it 100 times more likely in this patient to have donor acquired infection (Figure 2). This calculation assumes that the patient has the same risk of acquiring toxoplasmosis infection from ingesting oocysts as the general UK population.

Figure 2: Slide from the Yorkshire Retina Society presentation, 5 March 2014.

In transplant patients, severe or disseminated toxoplasmosis can result either from a reactivation of latent infection in the immunosuppressed recipient or infection from a cyst-containing organ from a seropositive donor given to a seronegative recipient, a situation where heart transplants carry the highest risk.

In cases of donor / transplant mismatch i.e. seropositive donor / negative recipient (D+/R–), the standard prophylaxis would be co-trimoxazole. It was interesting that our patient presented with her symptoms a few months after stopping prophylaxis.

It is, therefore, important to recognise toxoplasmosis in the immunosuppressed population including the elderly, in whom the condition may present atypically with multifocal lesions, low grade vitritis, larger lesion size with no scarring, bilaterality, optic nerve involvement and haemorrhagic vasculitis. Toxoplasmosis is a clinical diagnosis but if there is any doubt, particularly in this group of patients, an AC tap is a useful diagnostic test. The viral PCR results can be available in six hours and the volume of sample is not an issue as the extracted DNA can be sent to the National Toxoplasma Reference Unit in Swansea for analysis where standard turnaround time is 10 to 14 days.

We can reasonably conclude that this case represents donor-acquired infection that became active after the recipient’s co-trimoxazole prophylaxis ceased. Acute toxoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients can be rapidly lethal, its diagnosis is an emergency. In transplant patients, the control of toxoplasmosis may require a reduction of immunosuppressive therapy [3].

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Edward Guy, Head of Toxoplasma Reference Unit, Public Health, Wales, United Kingdom.

References

1. Jones JL, Dargelas V, Roberts J, et al. Risk Factors for Toxoplasma gondii Infection in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49(6):878-84.

2. Speirs GE, Hakim M, Wreghitt TG. Relative risk of donor-transmitted Toxoplasma gondii infection in heart, liver and kidney transplantation recipients. Clin Transplant 1988;2:257-69.

3. Robert-Gangneux F, Darde ML. Epidemiology of and diagnostic strategies for Toxoplasmosis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2012;25:264-96.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME