Case report

A 64-year-old female with diabetic maculopathy (DMO) underwent phacoemulsification with intraocular lens (IOL) implantation in her right eye combined with intravitreal triamcinolone (IVTA). Diabetes control was poor with HbA1c (IFCC) of 119mmol/mol and blood sugar level of 27mmol/L. She had no other systemic co-morbidities. Furthermore, DMO in the right eye had not responded to several previous laser treatments. At the time of surgery, anti-VEGF was not licensed for DMO therapy.

Routine phacoemulsification with IOL implantation was completed with watertight corneal wounds. However, the operation was complicated by administration of 20mg IVTA (instead of intended usual dose of 4mg).

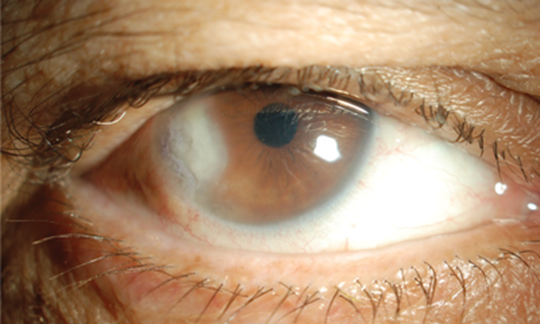

The patient received the standard institutional post-cataract treatment regime including Maxitrol and Acular. The early postoperative period was uneventful. At one month, right eye acuity had improved from 6/36 to 6/9 with improvement of central macular oedema. The patient re-presented acutely at six weeks with new symptoms of redness and reduced vision. There was a dense infiltrate following the entire track of the main corneal incision (Figure 1). However, there were no signs of endophthalmitis.

Figure 1: Slit-lamp photo of the cornea at first presentation.

This illustrates dense infiltrate along clear corneal incision.

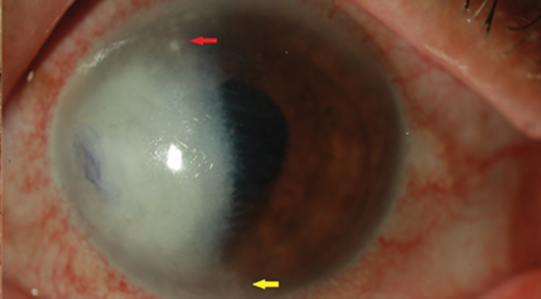

Initial results yielded evidence of Streptococcus pneumonia. Intensive topical hourly penicillin treatment was commenced with a good initial response. A tapered regimen was continued for a further five weeks while she was closely monitored. At month three (after cataract surgery), the patient’s eye deteriorated again. Vision had now reduced to count fingers and the eye was increasingly painful. There was signs of corneal perforation due to extensive stromal infiltration and thinning. There was associated hypopyon and satellite lesions were visible on the stroma (Figure 2). The perforation was sealed with Histoacryl glue. An aqueous tap and corneal re-scrape were obtained. Both specimens showed Fusarium dimerum. Intensive hourly topical natamycin 5% was instigated, with oral voriconazole 200mg. An intracameral injection of amphotericin B was also given. An alternative ocular preparation of voriconazole was not available for use.

Figure 2: Slit-lamp image of the cornea at subsequent visit. It shows an extensive dense infiltrate with feathery margin.

This is covering nearly half of the cornea. Red arrow is pointing to satellite lesions and yellow arrow directs to hypopyon.

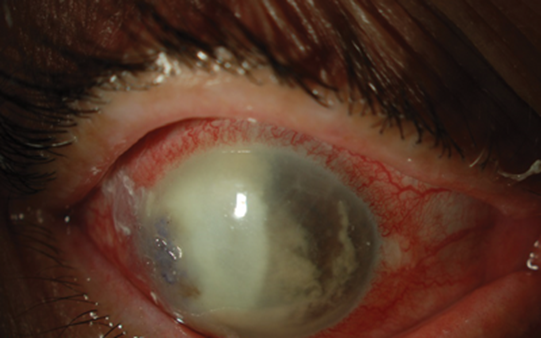

Figure 3: Slit-lamp photo of the cornea in the last visit.

This demonstrates the extension of dense infiltrate involving more or less the entire cornea.

Also the perforation is sealed with tissue glue.

Unfortunately, despite two months of antifungal therapy, the right eye was not salvageable. By month six (after cataract surgery), the eye had become blind and phthisical. The patient underwent evisceration to alleviate chronic intractable pain.

Discussion

Keratomycosis was first described by Leber [1]. It has long remained a challenge for ophthalmologists and in fact, the incidence has risen over the last few decades. Risk factors for keratomycosis include liberal usage of broad-spectrum antibiotics, steroid therapy, penetrating keratoplasty, poor diabetic control and contact lens wear [2].

The incidence of keratomycosis in the context of stromal keratitis varies between 15 to 20% [3]. However, the rate of fungal infection in sutureless corneal wounds is yet to be elucidated. Aspergillus sp. and Fusarium sp. are most commonly implicated [1,4,5] in humid areas whereas yeasts (Candida sp.) are more widespread in temperate climates [1,4,6]. Fungal keratitis associated with DM or previous surgery has only been reported in 6% of cases of keratitis [7]. The toxicity of Fusarium is related to secreted mycotoxin and its ability to proliferate at body temperature [7]. Fungi can easily breach Descemet’s membrane to gain access to the anterior chamber. The virulence of fungi is enhanced in the context of corticosteroid therapy or other forms of immune-suppression [7]. With the facilitation of single-use disposable instruments and a delayed presentation, inoculation at time of surgery was thought to be less likely in our case.

There is no reported consensus on appropriate treatment modalities, dosages or duration of therapy for fungal keratitis [8]. However, in general, topical amphotericin B 0.15% is widely used for keratitis due to yeasts. Topical natamycin 5% is most commonly employed against filamentous fungi [4,7].

Most topical anti-fungal agents have poor corneal penetration. As a result, topical treatment is usually only fungistatic. Additional complementary systemic therapy using fluconazole or voriconazole is often advocated [1,4,7]. Treatment outcomes in keratomycosis are usually poor [1,4]. There are some literatures supporting intra-stromal voriconazole administration in conjunction with topical anti-fungal therapy in cases of deep fungal keratitis [9].

Our patient received a high dose of IVTA. Typical doses of IVTA in the United States and the UK are 4mg and 2mg. In a study of 60 eyes, Jonas et al. did not find increased rates of endophthalmitis using 20mg triamcinolone combined with cataract surgery [10]. However, there was a caveat that safe conclusions could not be reached regarding differences in frequency of postoperative infectious endophthalmitis based on their study.

TAKE HOME MESSAGE

In the presence of diabetic macular oedema, it is more advisable to address the maculopathy first before considering any elective intraocular surgeries.

Acknowledgement:

Anita Reynolds and Simon Kolb.

References

1. Leber T. Keratomycosis aspergillina als ursache von hypopyonkeratitis. Graefes Arch Ophthalmol 1879;25:285-301.

2. Tanure M, Cohen EJ, Sudesh S, et al. Spectrum of fungal keratitis at Wills Eye Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Cornea 2000;19(3):307-12.

3. Mendicute J, Orbegozo J, Ruiz M, et al. Keratomycosis after cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 2000;26(11):1660-6.

4. Tuft SJ, Tullo A B. Fungal keratitis in the United Kingdom 2003-2005. Eye (Lond) 2009;23(6):1308-13.

5. Panda A, Sharma N, Das G, Kumar N. Mycotic keratitis in children: epidemiologic and microbiologic evaluation. Cornea 1997;16(3):295-9.

6. Galarreta DJ, Tuft SJ, Ramsay A, Dart JKG. Fungal keratitis in London: microbiological and clinical evaluation. Cornea 2007;26(9):1082-6.

7. Dursun D, Fernandez V, Miller D, Alfonso EC. Advanced fusarium keratitis progressing to endophthalmitis. Cornea 2003;22(4):300-3.

8. FlorCruz NV, Peczon IV, Evans JR. Medical interventions for fungal keratitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;2.

9. Sharma N, Chacko J, Velpandian T, et al. Comparative evaluation of topical versus intrastromal voriconazole as an adjunct to natamycin in recalcitrant fungal keratitis. Ophthalmology 2013;120(4):677-81.

10. Jonas J, Kreissig I, Budde W, Degenring R. Cataract surgery combined with intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide. Eur J Ophthalmol 2005;15:329-35.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME