I thank everyone for their time in responding to this edition’s survey questions.

The first question relates to an issue I have previously discussed around consent for second eye cataract surgery. I touch on this point again for two reasons. Firstly, I have had a medico-legal case come across my desk whereby a patient asserted that they were not appropriately consented for their second eye cataract surgery and would not have agreed to surgery if they knew there were risks of visual loss. The other reason is because I have had the heart sink experience of operating on a patient’s second eye and running in to complications when the first eye, done by another surgeon, went without issue or complication.

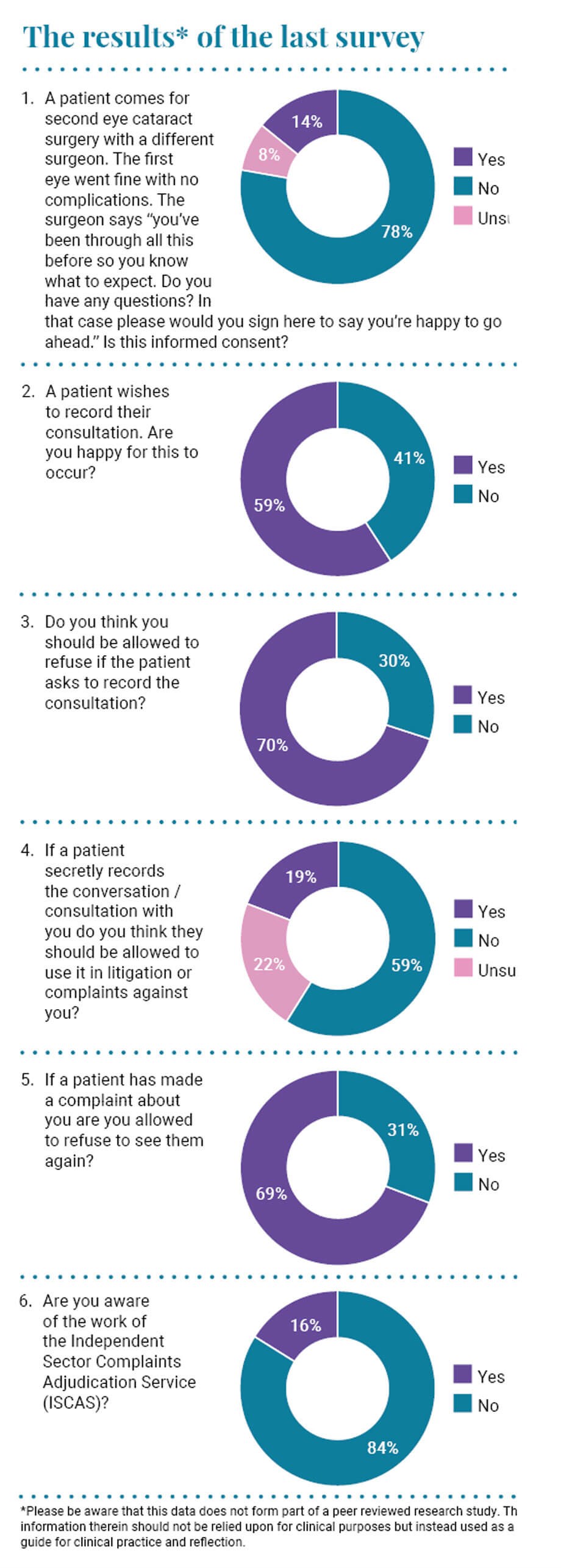

The question asked was if a patient comes for second eye cataract surgery, assuming a different surgeon to the first eye, then is it reasonable to explain to the patient that: “You’ve been through all this before, so you know what to expect. Do you have any questions? In that case please would you sign here to say you’re happy to go ahead.” I asked whether you felt this was informed consent. Most of you (78%) felt it was not, which I agree with; 8% felt this was acceptable and 14% were unsure.

A patient coming for a second eye cataract surgery is different to the one who came for their first eye. They have already had one eye done and it was easy and straightforward. Recovery was quick and there were no problems. They have a reasonable expectation that the procedure would be as easy this time as it was last time. They may have “been through this before” regarding the procedure and what happens, but they are not thinking about complications and the risks of surgery. Their attitude to the risks of surgery have changed. They “know” the procedure will be fine and there are no real risks because they have had it done already. They need to be reminded that the risks of the second procedure are the same as the first, albeit slightly reduced because we have had a trial run with the other eye, and it reacted predictably to surgery.

The allegation in the case I am dealing with is that the patient was unaware of any risks of second eye cataract surgery because she was told that it would be exactly the same as last time. She was required to sign a consent form with the risks on it, but they were not explained. I have some sympathy with the position and there is no real evidence to support the defendant’s position that the risks were explained again. We need to make sure patients are aware of the risks.

In my personal case I cannot help feeling the patient is secretly thinking: “If I had the surgeon I had for the first eye, this would not have happened.” I hate the fact that she had surgery the first time and it was fine and then she comes to me, someone who feels they are pretty good at cataract surgery, and I “messed up” the second eye. These patients need to be handled carefully as they can seek to complain and assert breach of duty. Thankfully, she was well aware of the risks. My usual spiel is: “You’re having your second eye done and the risks of this procedure are exactly the same as the risks of the first one. You can lose vision; you can even lose the eye. On the consent form are all the risks we explained before your first eye. I do not want to scare you, but it is important you know the risks. Fundamentally, one in 100 patients can end up with worse vision after than before and one in 1000 can go blind. One in 10,000 people can lose the eye.”

I do not know whether the above is entirely acceptable, but I feel I have fulfilled my duty to try and obtain fully informed consent. Naturally, we springboard to some degree from the consent for the first eye, and so it is important that that is done well and shown to be done well with appropriate documentation.

With smart phones being used more and more frequently, it is getting easier for patients to record their consultations. I have been involved in several cases where patients have covertly recorded their consultations, or, more commonly, follow-up appointments when things have not gone to plan, and the contents of these records are uncomfortable. They are professionally transcribed and make difficult reading sometimes. It is easy for us to come off as condescending and dismissive in our conversations, and we must consciously make efforts to avoid this perception. Fifty-nine percent of you were happy for patients to record their consultations, while 41% of you were not. I get asked questions on this topic frequently after my talks and teaching sessions. My response to this is that I cannot see any reason why we would not allow our patients to record their consultation. We need to inform the patient about their condition and treatment options, and we want to empower them to make decisions about their care. If they want to listen back to the recording or share the information with a relative to help do this, then I can see no ethical or reasonable objection. It may even be deemed to be essential under the equalities legislation when a patient may struggle to absorb all the information in their appointment. I would ask: “What have we got to hide?”

Seventy percent of you feel that you can refuse to allow a patient to record the consultation. I am not so sure, and to my knowledge this has not been tested in the courts. If a patient wants to record the conversation to aid in their care, then your refusal may be seen as a failure to fulfil your professional obligation to them. I certainly do not think that you can discontinue the consultation. We could argue that a doctor’s common law privacy rights are likely to be engaged, but this will have to be balanced against the benefit to the patient. I think that the latter is likely to hold more sway. If you are still unhappy about the patient recording the conversation, I would advise speaking to your hospitals legal team, the British Medical Association (BMA), or your indemnity provider to get clarity as to your position.

When the patient covertly records the consultation, the situation is trickier. Sadly, I do not believe the doctor has any legal redress. My feeling it that the consultation represents the patient’s personal data, and they should be allowed access to it.

When asked if a patient can use secretly recorded conversations / consultations with you in litigation or complaints, 59% of you said no, 22% of you were unsure and 19% said yes. I am afraid the answer is that they can, and more and more, they will be used for these purposes.

When asked if you are allowed to refuse to see a patient who has made a complaint about you, 69% of you responded yes. I do not think there is a clear-cut answer, and it all depends upon the nature of the complaint. Often the best way to resolve a complaint is to see the patient again and try to communicate with them and reach common ground. If the patient has clearly lost faith in you, then it can undermine the whole clinical relationship and calls into question the utility of a further consultation. It also places the Sword of Damocles firmly over your head, as you will be fearful of further consequences / complaints if the patient remains unhappy with the care provided. If someone has already complained about a poor surgical outcome, then would a surgeon be comfortable undertaking complex remedial surgery with the fear of further complaint / litigation if it did not go to plan? I think speaking to your indemnity provider or your hospital’s legal team is essential in this scenario.

Eighty-four percent of you were unaware of the Independent Sector Complaints Adjudication Service (ISCAS). ISCAS provides independent adjudication on complaints about ISCAS subscribers. It is a voluntary subscriber scheme for the vast majority of independent healthcare providers, and acts as an adjudicator for the private healthcare sector. If complaints cannot be resolved by the private health organisation, they can be referred to the ISCAS for adjudication.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME