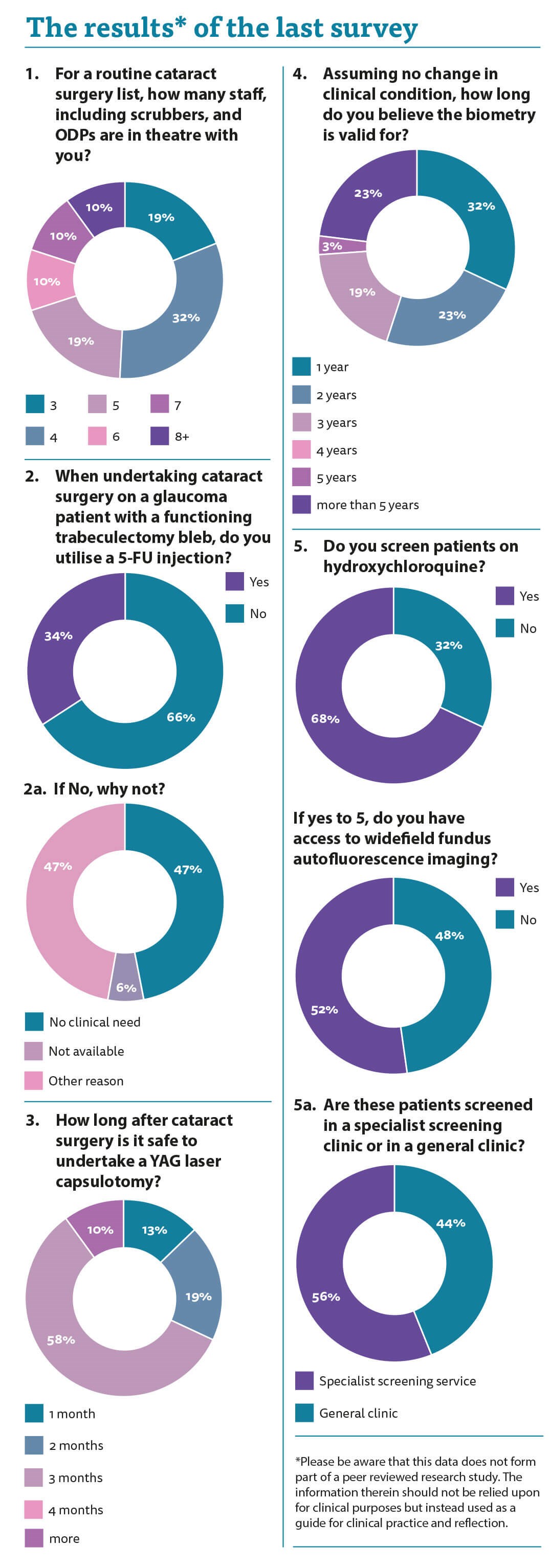

Thank you once more for your time in answering the latest survey. The first question relates to the number of staff required for a routine cataract list. There was a big variance in practice. Some of us are luckier than others it seems!

There was no real pattern with variation from three staff to eight or more. One half of us had four or five members of staff with us which I believe it the sweet spot for numbers to ensure that there are enough people around to keep the list running smoothly and efficiently. Safety is also a big concern. I believe three staff is too few. If one member of staff is readying the next patient so the list runs efficiently that leaves two staff. One scrubber, one person to help the scrub nurse means that there is no one spare to look after the patient. If something goes wrong and we have to ask for extra equipment, we are suddenly severely undermanned. Patients pick up on this as they are awake and listening to everything that is happening.

Many times, I have seen statements from patients in litigation cases where they state they overhead the surgeon asking for equipment that was not there and the allegation is that they did not have the equipment to hand. More than likely it was simply asking one member of staff for a capsular tension ring and the other member of staff not knowing exactly where it was and having to ask.

The Royal College of Ophthalmologists Ophthalmic Services Document on High Flow Cataract Surgery (Version 2.0, January 2022) comments upon the number of staff in theatre. It states: “In theatre there should be a minimum of two scrub practitioners and one runner, each trained with signed off competencies, per list. The cataract drive at Moorfields benefited from an extra scrub nurse, with three per list. Sunderland, widely regarded as a gold standard case study of high flow cataract surgery, were able to supplement their two scrub practitioners and one runner with an additional four to five primary nurses on high volume lists and three on training lists. Fife and Stoke Mandeville, however, both deliver high flow lists using only the minimum 3 staff, notwithstanding Stoke Mandeville’s floating operating department practitioner (ODP). Some units are pursuing the use of dedicated cataract scrub technicians to expand the workforce.”

When I was a glaucoma surgeon, many moons ago, I always used to inject 5-FU at the time of my cataract surgery in a patient with a functional trabeculectomy. I know the effort it takes to create a functioning trabeculectomy bleb with potentially several needlings, heartbreaking hypotonous phases and annoying scarring. After all that, it appears only fair that we try and preserve the bleb function. One third of us inject 5-FU at the time of surgery while the rest do not, with half of those saying there is no need.

Although the exact mechanism of bleb failure after phacoemulsification is poorly understood it is likely that scar tissue forms at the conjunctival-scleral or scleral flap in response to the inflammation caused by cataract surgery. Additionally, cataract surgery is thought to cause prolonged low-grade inflammation secondary to lens crystallins, the effect of ultrasound energy, and the high volume of fluid passing through the eye, all of which likely increase the production of fibrogenic cytokines in the aqueous, leading to further scarring [1].

Despite numerous studies concerning the effect of phacoemulsification on the function of the filtering bleb there is still no real consensus. In 2002, Friedman et al. conducted an extensive review of the literature and concluded that the data was inconclusive as to whether cataract extraction negatively affects pre-existing blebs [2]. Chen et al., however, found that patients under the age of 50 who had a preoperative IOP above 10mmHg, intraoperative iris manipulation, an early postoperative IOP over 25mmHg, and cataract surgery less than six months after trabeculectomy were all at risk of reduced bleb function after cataract extraction [3].

Several other studies have demonstrated that postponing cataract surgery by more than six months reduces the risk of bleb failure. This period permits the bleb to stabilise and allows low-grade subclinical inflammation to resolve. A newly formed bleb in its infancy may be unable to withstand the stress of phacoemulsification [4,5]. A subconjunctival injection of 5-FU at the time of surgery has been advocated as a bleb protection measure.

I was taught that we had to wait three months after cataract surgery before undertaking a YAG laser capsulotomy, but I was never particularly clear as to why. I presumed it was because there was a risk of the IOL displacing because it was not held firmly in the capsular bag but now, I find that unlikely. I also think it makes sense to avoid a gap in the capsule while the blood-aqueous barrier is still broken down as there may be a risk of cystoid macular oedema, but I could find no real evidence base for this assertion. Like me, the majority wait for at least three months, whereas 13% only wait a month and I presume they do not run into difficulties.

On to the next question I thought there would be clear consensus but am again surprised by the variance seen. There was a large spread of opinions as to how long a biometry was valid for with an even spread of opinions stating one, two and three years with 23% saying that it is valid for more than five years. I do not know what the answer is, but this response makes me question my opinion on a case I opined on some time ago where there was an allegation that using a biometry more than five-years-old was a breach of duty. Clearly, we have a reasonable body of medical opinion supporting this view.

The last question was regarding screening for patients on hydroxychloroquine. More than two thirds of us are doing it while almost half do not have access to wide-field fundus autofluorescence (FAF). There is also almost a 50:50 split between screening in specialist versus general clinics. I presume the patients seen in the specialist clinics are the ones that have the FAF while the ones in the general clinic do not. I think this highlights the problem with guidelines and guidance as, logistically, sometimes equipment is not widely available, and it is unreasonable to criticise for not adhering to guidance when it is impossible to do so.

References

1. Sirwardena D, Kotecha A, Minassian D, et al. Anterior chamber flare after trabeculectomy and after phacoemulsification. Br J Ophthalmol 2000;84:1056-7.

2. Friedman DS, Jampel HD, Lubomski LH, et al. Surgical strategies for coexisting glaucoma and cataract: an evidence-based update. Ophthalmology 2002;109:1902‑13.

3. Chen PP, Weaver YK, Budenz DL, et al. Trabeculectomy function after cataract extraction. Ophthalmology 1998;105:1928-35.

4. Manoj B, Chako D, Khan MY. Effect of extracapsular cataract extraction and phacoemulsification performed after trabeculectomy on intraocular pressure. J Cataract Refract Surg 2000;26:75-8.

5. Awai-Kasoaka N, Inoue T, Takihara Y, et al. Impact of phacoemulsification on failure of trabeculectomy with mitomycin–C. J Cataract Refract Surg 2012;38:419-24.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME